How Did U.S. Workers Get The 8-Hour Workday?

Across the globe and throughout history, workers have repeatedly fought against exploitation, whether it came in the form of workplace safety, wages, or workday length. And as more and more people are questioning whether or not the 5-day work week should be shortened — per Vox and Forbes — it's worth remembering where the current 40-hour workweek came from because it didn't just appear out of thin air.

Labor rights have always been a controversial topic in the United States, to the point where the country celebrates Labor Day on September 1 instead of May 1 because President Grover Cleveland didn't want the holiday linked with the Haymarket Affair. According to CNN, this association would've also connected the holiday with the eight-hour workday movement.

The eight-hour workday was a long-fought and hard-won battle that took workers over 100 years to manifest into federal law, but was it really a victory for all workers? This is how U.S. workers got the eight-hour workday.

The 10-hour working day

Before the eight-hour workday was normalized, a typical workday for an American worker lasted up to 11 or 12 hours but could've been as long as 16 hours. Meanwhile, enslaved people worked up to 16 hours and had their labor profits stolen, per The Washington Post. But as early as the 18th century, workers were striking for shorter working days. One of the first recorded strikes for a shorter workday was held by Philadelphia carpenters in 1791, but unfortunately, their strike was unsuccessful, per the U.S. Department of Labor.

As the years went by, more and more workers started pushing for 10-hour workdays. According to the Congressional Record of the 75th Congress, in 1822, mechanics, millwrights, and journeymen all struck for a 10-hour working day. And although these strikes were similarly unsuccessful, public attention was finally drawn to the issue. Indeed, workers across New England began striking for a 10-hour workday, and by 1835, workers in New York and Philadelphia won the 10-hour workday, per Vintage News. Many protested with banners that read: "From 6 to 6, ten hours work and two hours for meals."

On March 31, 1840, President Martin Van Buren issued an executive order that mandated a 10-hour day for federal employees. And in 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a law making 10-hours the legal workday. However, the law applied only to those who weren't under a private contract, and few workers actually saw any changes.

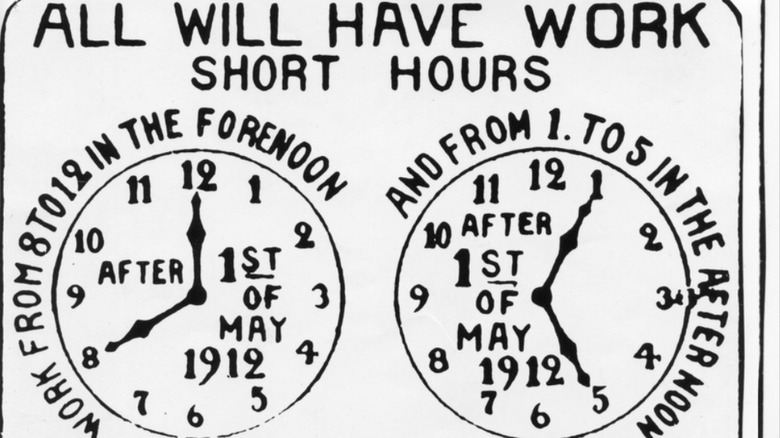

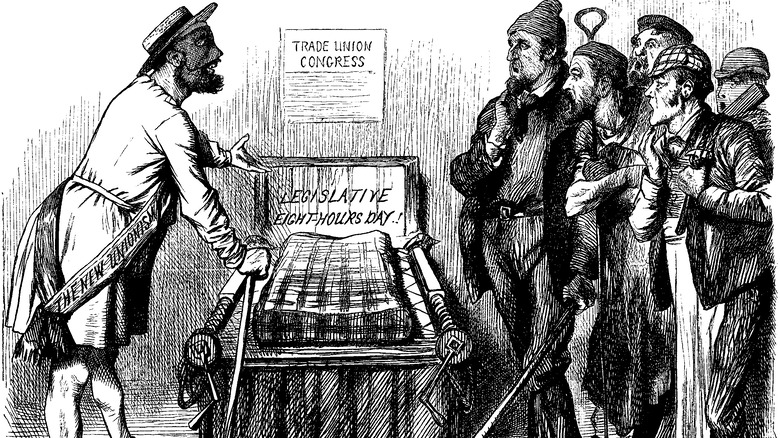

Demands for 8-hour days

As early as 1836, workers were going further and demanding an eight-hour workday. It took another six years before Boston ship carpenters became some of the first to establish an eight-hour workday, but by 1842, workers saw that an eight-hour workday wasn't an impossibility. In 1864, Teen Vogue wrote that the International Working Men's Association announced that the shorter workday was "the first step in the direction of the emancipation of the working class." In response, workers ranging from Chinese railroad workers to New York City tradesmen went on strike over the following decades, demanding an eight-hour workday.

In some places, like Illinois, state laws were passed that limited the workday to eight hours, but they included loopholes and contradictions that essentially rendered the law null and void. According to the "Encyclopedia of Populism in America," President Ulysses S. Grant signed the National Eight Hour Law Proclamation in 1869 in response to workers' calls for an eight-hour workday. However, the recommendation of an eight-hour workday in the law applied only to federal workers. And even when laws did exist in cities and states, they didn't apply to workers in privately-owned offices and factories, per Chicago History.

A network of local Eight-Hour Leagues was created, and it held rallies, tried to negotiate eight-hour workdays, and sought change through political action. And in response, in some places like San Francisco, employers created their own "Ten-Hour League Society," but they were ultimately unsuccessful, writes Found SF.

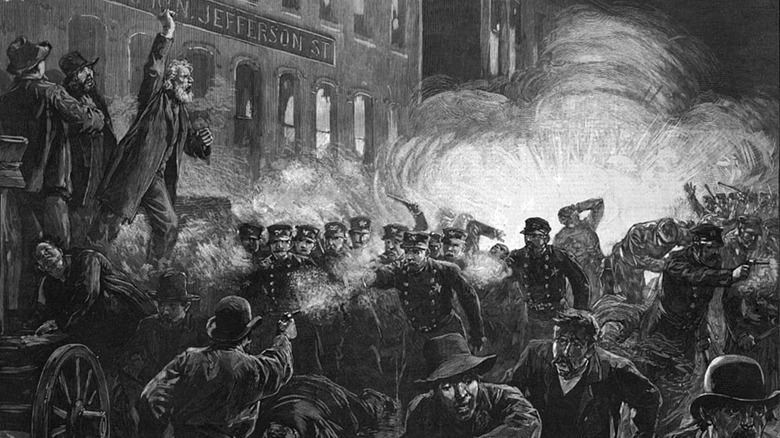

May Day

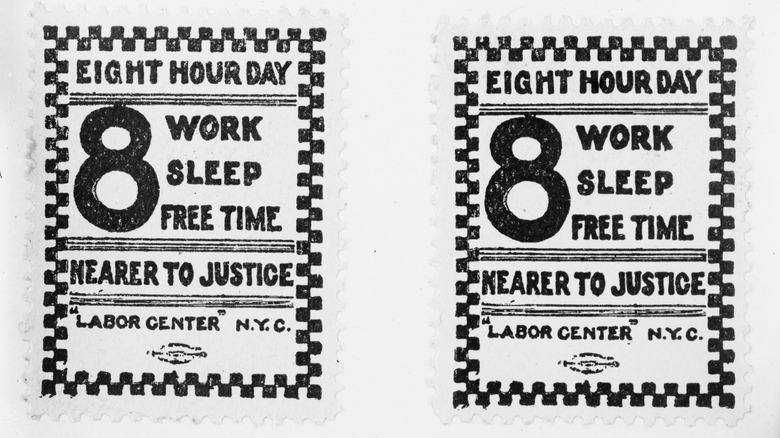

In 1886, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions called for a nationwide strike for an eight-way workday on May 1. Ohio History Central writes that thousands of workers in major cities across the United States answered the call, with 40,000 workers striking in Chicago, 10,000 striking in New York, and 11,000 striking in Detroit, effectively beginning the tradition of May Day with the first celebration in the world. Teen Vogue writes that Lucy and Albert Parsons essentially led the first May Day parade as they marched down Chicago's Michigan Avenue with thousands of workers, chanting, "Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will!"

WNIJ reports that during the peaceful protests in Chicago, police violence led to the deaths of several strikers on May 3. The following day, as upwards of 3,000 people showed up in Haymarket Square to protest police brutality, a homemade bomb went off, killing seven police officers and an unknown number of protestors. Although anarchists were blamed for the bomb and several were executed after a subsequent sham trial, the incident known as the Haymarket Affair is considered to be "one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in American history," writes Chicago Time Machine.

Arguments for and against the 8-hour workday

Throughout the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, workers continued fighting for shorter workdays in the six-day week since the workweek was Monday through Saturday. Those who advocated for eight-hour days argued that it would not only increase worker productivity but it would increase consumption and help the economy as well, according to the American Law Library. And thanks to the Industrial Revolution, workers also wanted shorter hours to reduce the risk of injury.

In "Redeeming Time," William A. Mirola writes that there was also a religious message associated with the eight-hour workday, in the sense that the time gained could be used for spiritual reflection. But by the turn of the 20th century, the message became "completely secular rhetoric based on economics." Meanwhile, employers repeatedly insisted that a reduction of hours would negatively affect productivity. But as the "Hearing Before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce" notes, this "consistently failed to come true." As William Sulzer underlines in the "Hearings Before the Committee on Labor of the House of Representatives," the same arguments against reducing the workday were reused every time movements arose to shorten the workday, whether it was a 14-hour workday or a 10-hour workday. The claims about lost productivity were "made before, and they are as old and as hoary as they are false and presumptuous. They deceive nobody but themselves."

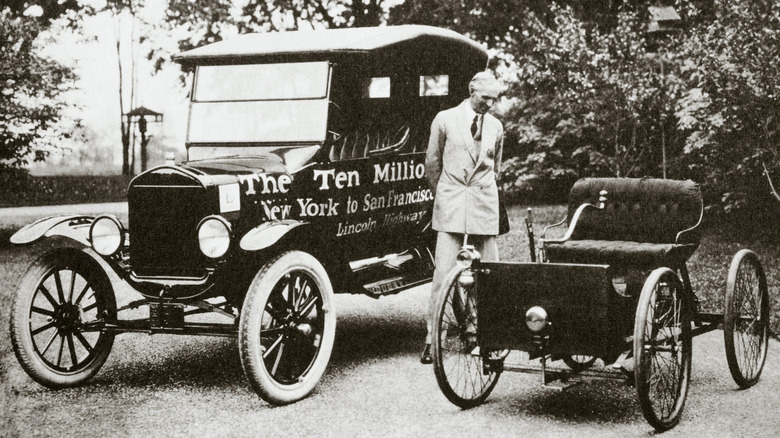

Henry Ford and the 8-hour workday

In the 1910s, when Henry Ford realized that the tide of the eight-hour workday was going to sweep through his own factories, he decided to implement the eight-hour day himself. But he didn't do this out of goodwill towards his workers. Instead, according to "Work Time" by Cynthia L. Negrey, Ford hoped to disable the influence of the Industrial Workers of the World, who were leading strikes in other factories. In addition, worker turnover and truancies were high at Ford's factories, and Ford hoped that the eight-hour workday coupled with the higher pay could keep workers at his factory.

And in the end, it worked. Labor turnover fell by 90%, and truancies were "at least halved." In "Henry Ford," Gerry Boehme writes that Ford called his system a "prosperity-sharing plan" rather than a simple wage hike, but newspapers lauded his plan, describing it as an agreement "to share profits with workers." Ford reportedly encouraged President Woodrow Wilson to include an eight-hour workday in his 1916 presidential platform, but Wilson declined. However, that same year, Congress provided the eight-hour workday to some railroad workers as well as children aged 14 to 16 who worked in interstate commerce.

Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938

By 1919, almost half of all agricultural workers and a majority of organized workers had attained an eight-hour workday. Riding this momentum, some unions like the United Mine Workers started fighting for 6-hour workdays, Negrey writes in "Work Time." And in the 1930s, the Industrial Workers of the World started to push for a four-hour workday in a four-day workweek, per Vice.

But the eight-hour workday/40-hour workweek wouldn't become federal law until 1938. Politico writes that during the Great Depression, one of the acts enacted by Congress as part of the New Deal established maximum hours for workers. Although it was struck down in 1935 by the Supreme Court, it was replaced by the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which mandated overtime pay if workers worked over 44 hours a week. Two years later, this was amended to 40 hours, thus instilling the eight-hour workday into American life.

However, noted in "A Cultural History of Work in the Modern Age," this law only applied if a worker was "designated as meeting the legal definition of 'employee' in order to be within the 'boundaries of workplace democracy.'" As a result, this allowed some workers to be classified as "semi-professionals" or "technicians" in order to keep them actualizing their rights as workers since they weren't considered employees.