Ragnarok: The Untold Truth Of The Norse Myth

The end of the world is a scary thing. Whether you believe that it could come as a result of human-caused catastrophes or divine intervention, few people really enjoy thinking about everything crumbling down around us. But what if the end of the world involved a huge wolf, gods battling it out with fire giants, and a few volcanoes? Even if you weren't one of the lucky survivors, you could at least briefly enjoy a spectacle that sounds a lot like the cover of a metal album.

Such is Ragnarök, the old Norse myth of the end of the world. And while it may seem fairly simple on its surface — gods and demon-like creatures battle, the old world ends, a new one rises from the ashes — the story of this legend is deeply complex and fascinating. Consider the fact that Ragnarök the tale can tell us quite a lot about the real world, from the effects of Icelandic volcanoes to the more metaphorical seismic shifts in religion that shaped the story. This is the untold truth of the Norse myth of Ragnarök.

Most of our information about Ragnarök comes from two sources

Getting direct information about Norse mythology, much less the bloody, high-octane spectacle of Ragnarök, is surprisingly difficult. That's because the Norse people didn't originally write everything down, preferring instead to carve things into stone or recite their tales in oral form, per the World History Encyclopedia. It wasn't until the medieval era that the descendants of the pagan Vikings began writing things down.

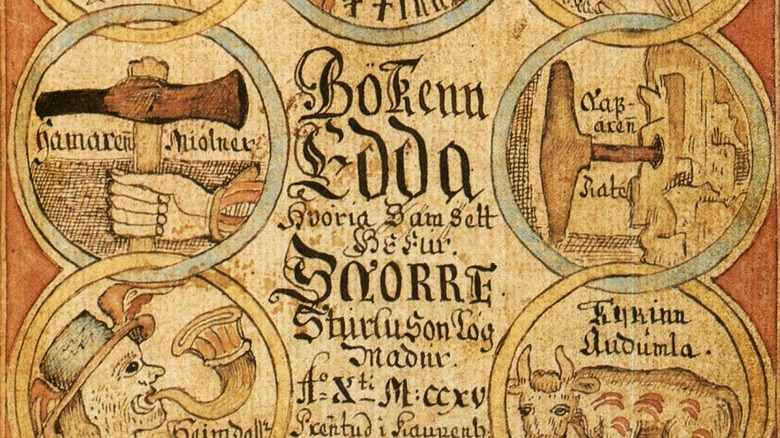

And so our greatest source of information about Ragnarök comes via the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda, medieval compilations of earlier Norse myths. According to ThoughtCo, we can be pretty certain that the Prose Edda was written down in Old Norse by Snorri Sturluson, a historian living in 13th century Iceland. The Poetic Edda appears to have been written down around the same time, but with an attributed author.

Researchers still think the core story may have been written down as early as the 6th century CE, going by the changes in linguistic forms that seem to have been tracked somewhat in the text of the Völuspa, or Seeress' Prophecy, included in Sturluson's Edda. (via ThoughtCo). That puts it ahead of the seafaring Vikings by at least a couple of centuries, if not a bit longer. However, the first confirmed text of the Völuspa, which portends the doom and gloom of Ragnarök, didn't appear until the 11th century.

The tale of Ragnarök is based on upending Norse cosmology

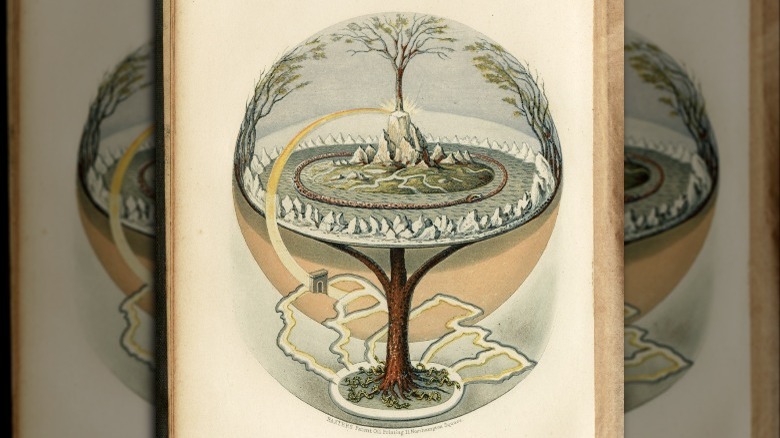

For Ragnarök to happen, all of the givens of the ancient Norse world must be upended. To fully get it, we need to understand the Norse cosmos. First, according to the World History Encyclopedia, there are the nine realms. Most accounts generally indicate that the realms in question radiate out in some way from the base of Yggdrasil, also known as the World Tree.

Early Norse storytellers apparently assumed that everyone already knew the nine realms, while later Christian writers in the medieval period either weren't in on the details or didn't care to include them in the written accounts. We can at least be reasonably certain of a few details, like how Asgard was the realm of a class of gods known as the Aesir, Jotunheim was for the fearsome giants, the gods known as Vanir were in Vanaheim, and regular old humans resided in Midgard.

And, far from being just some plain tree, Yggdrasil was a pretty big deal. The Public Domain Review notes that its roots were believed to reach down into the underworld, while the branches stretched fantastically high. Three mythical women, known as the Norns, care for the tree with sacred water. Given that the roots of Yggdrasil appear to hold everything together, it's pretty imperative that the Norns do their job well. For, if the World Tree dies, then so, too, will the gods and just about everything else in their wake.

Ragnarök begins with ominous portents and calamities

Like any good apocalypse story, things start off seemingly small, with ominous portents and, one assumes, a strange feeling in the air. But those eerie signs increase in intensity and overall creepiness as the incredibly bloody finale of Ragnarök approaches. As ThoughtCo relates, it's all supposed to begin with, surprisingly enough, a bunch of roosters crowing. Specific birds wake the members of select realms; the Aesir in Asgard get alerted to their looming end by a rooster with a luxe golden coxcomb on its head. Helheim, the Norse version of the underworld that's ruled over by Hel, daughter of Loki, is graced by the sounds of a frightening hellhound. Then, everyone proceeds to turn against one another, bringing about conflict and betrayal.

Then, the winter comes. Or, rather, a series of harsh, unrelenting winters that are marked by the disappearance of the stars, moon, and sun — which are gobbled up by the sons of the humongous wolf, Fenrir. And, as if that weren't bad enough, earthquakes shake the realms and tear apart the land. The giant Midgard Serpent leaves his normal spot (circling the nine realms with his tail in his mouth, of course) and swims through the oceans to the battlefield, causing great floods in its wake. And, all the time, the snow falls and the cold wind blows through the land.

This tale spells a bloody end for many Norse gods

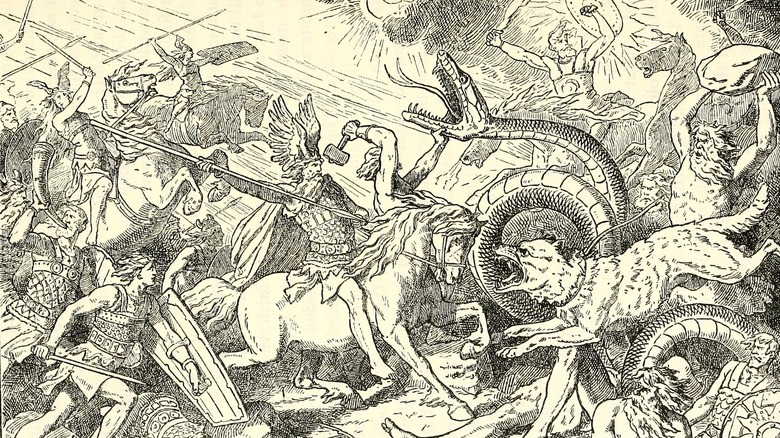

After the harsh winters do their damage to the nine realms and everyone in them, it's pretty obvious to the gods that battle is brewing. If it wasn't, it certainly becomes apparent when the fire giants make their way from Muspelheim, led by Surtur. Other gods and humans get in the bellicose spirit and start assembling for war, too (via ThoughtCo).

The site of their ultimate showdown with, well, everyone else? A field known as Vigrid (also known as Vígríðr) where broad battle lines between Surtr's forces and the gods will be drawn. It's already been mentioned once before in the Poetic Edda, where Odin, in the midst of a battle of wits with a jotunn, mentions that the final battle will take place on this massive plain (via "Influences of Pre-Christian Mythology and Christianity on Old Norse Poetry").

At this point, there have been three years of terrible winter, so perhaps it feels good to the gods to stretch their legs a bit. But, with all of the subsequent bloodshed and the many, many bodies left on the field, that sort of small joy must be very brief indeed. Divine watchman Heimdall and Loki face off, managing to kill one another (via Britannica). And, according to the Prose Edda, fire giant Surtr will kill Frey, in large part because the Aesir will have apparently forgotten his good sword. Surtr will also eventually engulf the world in fire.

Odin will be killed by Fenrir

Things really start to get dramatic when individual gods face off against individual representatives of evil and chaos, like a series of cinematic one-on-one battles. And Odin, though he has the advantage of being chief god, isn't spared a spectacularly gory fate at the hands of — what else? — a giant, ravening wolf.

Said wolf is actually Fenrir, a massive wolf who's also a son of trickster god Loki. According to the World History Encyclopedia, Fenrir seemed to be more or less minding his own business when the Aesir came along. They'd gotten wind of a prophecy that Loki's children would cause massive trouble for the gods (like, oh, the end of their world). Fenrir was tricked into chains by Odin. It's made all the more sad by one tale, where Fenrir's former friend, Tyr, volunteers to guarantee the other gods' behavior by putting his hand in the wolf's mouth. When Fenrir realizes he's been betrayed, he snaps his jaws shut and Tyr is left with one limb noticeably shorter than the other.

Before you feel too bad for the wolf-child, Norse audiences would have surely interpreted this beast as plenty fearsome and already associated with some pretty evil spirits and goings-on, so their sympathy may have been pretty limited. At Ragnarök, however, Fenrir breaks free from his chains and attacks Odin on the plains of Vigrid. The massive wolf kills Odin and then is killed by Vidar, Odin's son.

Thor and the Midgard Serpent dramatically battle

Also known as the Midgard Serpent or the World Serpent, Jörmungandr is a stupendously large snake, so big that he can wrap his body around all of the world, according to the World History Encyclopedia. He's actually one of three children of Loki who, with a giantess known as Angrboða, produced Fenrir, the Midgard Serpent, and a daughter, Hel. When the Aesir spirit away the potentially dangerous children, Fenrir is stuck with his rock, Hel is put in charge of the distant and cold underworld and its dead, and Odin flings Jörmungandr into the ocean.

Normally, Jörmungandr is supposed to be quietly sitting around the world with his tail tucked into his mouth. And he does just that, normally, though he shows up in a few Norse myths, oftentimes tangling with Thor, the powerful god of lightning and thunder. But, with the beginning of Ragnarök, Jörmungandr starts to move through the ocean and makes his way to the big battle.

He seems to have an especial hatred for Thor, what with all of their previous tense encounters. This time, it's a proper battle between the two. Thor manages to kill Jörmungandr, but the Midgard Serpent doesn't die without some satisfaction. He manages to so thoroughly soak Thor with his venom that, like in a dramatic movie, Thor can only walk nine steps before he drops dead in the middle of the battle.

Ragnarök isn't exactly about the end of the world

All of this business about gods fighting giants, wolves, and massive, realm-encompassing snakes sounds bad. And, if you were to stand on the field of battle and survey all the destruction — not to mention the missing stars and horrible weather — you may conclude that this is the end of absolutely everything. How can the world recover when the sun's been eaten, after all?

Now, it is true that, as the World History Encyclopedia notes, this is definitely the end for some Norse gods, like Thor and Odin, as well as their infernal counterparts. But it's not all over by a long shot. A few textual sources indicate that Ragnarök will be followed by a period of renewal and a new order of gods and humans. Some of the survivors include Thor's children and two of Odin's sons, Vidar and Vali. Frigg, Freyja, and Idun also make it through. Hel may also lose quite a bit of her hold over the underworld, as some previously dead gods, like Baldr, are said to make their way back to the land of the living (no such luck for Odin or Thor, however).

This may be one of the clearest reflections of Christian belief in the written text, according to some scholars. The idea of rebirth and rebuilding may have been especially resonant with Norse people who were watching their old gods "die" and be replaced by a new one.

Two humans will rebuild our species after Ragnarök

You may think that, with all of the earth shaking and deities and semi-divine beings battling at Ragnarök, regular old humans are doomed. None of us can command the power of lightning or superhuman strength, for example. And when was the last time any of us was large enough to encircle the earth or command an army of giants? So, it seems pretty clear that us soft-bodied, non-magical folks are pretty thoroughly doomed, even if we leave a careful distance between us and Fenrir.

But, dire as things may sound for plain old humanity, even a cataclysm like Ragnarök isn't enough to get us down for too long. According to "Evergreen Ash: Ecology and Catastrophe in Old Norse Myth and Literature," two people, Líf and Lífþrasir, manage to survive by hiding in the woods and only emerging after the destruction is over.

Some theorists link the details of the story to the cyclic nature of Ragnarök and other Norse myths, while others note that old myths even claim that humans emerged from trees (via "Norse Mythology"). And while the original sources like the Prose Edda are pretty mum about any other details of this Edenic pair, it's clear that they're key to continuing on after a seeming apocalypse.

There are links between Ragnarök and Christianity

By the time the Poetic Edda was compiled in the early Middle Ages, Christianity was pretty well established in Norse lands and the old ways had begun to fade. So, though it draws on earlier pagan sources, the Christian influence in Ragnarök is clear in the Poetic Edda and other written sources, per the World History Encyclopedia.

Though we can't be sure of the exact content of the earlier oral stories, it's possible that all of the messages about rebirth and a better tomorrow in the wake of Ragnarök are linked to Christian ideas about the apocalypse. After all, some gods, like the beloved Baldr, are said to return from the dead once the battle's over, maybe echoing the Christian hope of resurrection.

But it's not as if things changed overnight, and it certainly doesn't appear that the old pagan ways of believing disappeared entirely. "The Archaeology of Britain" notes that some stone monuments striking combine both old Norse and new Christian imagery. A stone cross from Gosforth, a village in Cumbria, England, shows not only a pretty standard image of the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, but one Ragnarök as well.

There's archaeological evidence that people feared Ragnarök

Though the Norse people didn't really write things down until their medieval descendants converted to Christianity and got hold of some ink and vellum parchment, there's still some good evidence that they thought about Ragnarök and perhaps even feared its approach. We just have to look at some rocks.

These aren't just any rocks, though. Various stone carvings surviving from medieval Norse territories appear to depict the events of Ragnarök. A cross from the English village of Gosforth depicts both the Crucifixion and Ragnarök, per "The Monstrous Middle Ages." Specifically, the pagan-inspired scene in question shows a man spearing a monstrous animal. Some researchers have concluded that this is Vidar killing the wolf Fenrir in retaliation for destroying Odin.

And, as "Runic Amulets and Magic Objects" reports, the Ledberg stone created to honor the memory of a Swedish man named Thorgaut also depicts scenes from the Norse apocalypse (we can't be sure if that was Thorgaut's particular thing, or if the people left after his death found the scenes comforting somehow).

Some think Ragnarök was inspired by real volcanic eruptions

Modern readers may take comfort in reminding themselves that the ultra-dark and bloody tale of Ragnarök is just that: a story. And we can be pretty certain that we're not living on a flat disk encircled by a gigantic serpent, or that giants and gods will rip said disk apart.

But that doesn't mean the tales of Ragnarök weren't inspired by real world events. Science writer Alexandra Witze suggests that the highly geologically active island of Iceland may have something to do with it. After all, the particulates and gases released by volcanoes can affect the climate, spelling cold, harsh winters in a land that's already notorious for frigid temperatures. And ash could also block out peoples' views of the skies above, perhaps leading some Norse folk to claim (seriously or otherwise) that the very stars had been gobbled up by monsters. Witze specifically points to the 870 CE eruption of the Icelandic volcano of Bárðarbunga, while other scientists think the 934 eruption of Eldgjá might have something to do with Ragnarök, too.

Stories of intense winters and the stars being blocked by darkness may be linked to early medieval volcanic eruptions in places like Iceland. Going even farther back, sciencenorway.no reports that other scientists believe a catastrophic shift in climate may have produced freezing temperatures about 1,500 years ago, perhaps planting the seed of an idea for the deadly cold winters of Ragnarök.

Ragnarök has made its way into modern pop culture

From comics, to superhero movies, to modern TV shows grappling with climate change, the dramatic upheaval of Ragnarök (and its promise of renewal after chaos) has proven irresistible for many modern creators. Simply put, it's a great story with all of the high drama and bloody consequences so beloved by modern audiences. Plus, it's also public domain.

The Marvel movie "Thor: Ragnarök" does draw somewhat on the myth, bringing in Surtr and briefly featuring Fenrir. But, as Tor notes, there are plenty of departures, like making Hel the daughter of Odin and bringing in Jeff Goldblum (though we suppose there's nothing saying he wasn't at the Norse Ragnarök, if you want to quibble over details).

Then, as Study Breaks notes, there's "Ragnarök," the first known TV and streaming series to address the myth and which also comes out of a Scandinavian country. Intriguingly, the series draws upon the ecological themes of the Ragnarök myth, keying into modern anxieties about climate change to portend another mythical apocalypse.