The Messed Up Truth About National Holidays

There are exactly 11 national holidays recognized by the United States. These are supposed to be days set aside for celebration, for honoring those who serve us, and for remembering our history — both good and bad. In practice, we tend to treat these holidays as days off. We incorporate them into our vacations and weekend plans, we throw parties, and we often don't give a lot of thought to the reason behind the day.

Which is unfortunate, because there's a lot going on behind that boldface phrase on your calendar. And while the official inspiration behind U.S. holidays is generally positive, the true story behind the origins or the practice of these celebratory days is sometimes complex, to say the least. Like many things, there's the official story we're taught in school, and then there's the more nuanced reality that you only learn if you pay close attention.

Just because our holidays have a dark side, that doesn't mean we should all stop celebrating them immediately. But a fuller understanding of the true stories behind these 11 days might make your celebrations more thoughtful — because some of the facts behind the days are a little jarring. Here is the messed up truth about national holidays.

New Year's Day: The deadliest day of the year

New year celebrations are iconic. This is a secular and (largely) non-partisan holiday that everyone can celebrate, no matter their cultural, spiritual, or political beliefs. Even if you follow a calendar that schedules the new year on a different day from the majority, you can still go and party your butt off.

But that partying is the problem. New Year's Eve has become so closely associated with wild parties that the following day has become the deadliest day of the year — by a pretty wide margin. The National Safety Council estimates nearly 400 people may die on the road over the holiday, largely due to impaired driving as people leave those parties and convince themselves they're fine to drive. AAA notes that New Year's Day is always one of the deadliest days of the year in terms of alcohol-related traffic deaths.

But there's more to it. According to the Independent, deaths in general are much higher on New Year's Day — a typical January has anywhere from 40,000 to 60,000 more deaths than other months of the year, with the majority centered around New Year's Day. Possible explanations range from seasonal depression to understaffed hospitals and the tendency to ignore health warnings because people are reluctant to bother people during a party, or simply don't want to leave.

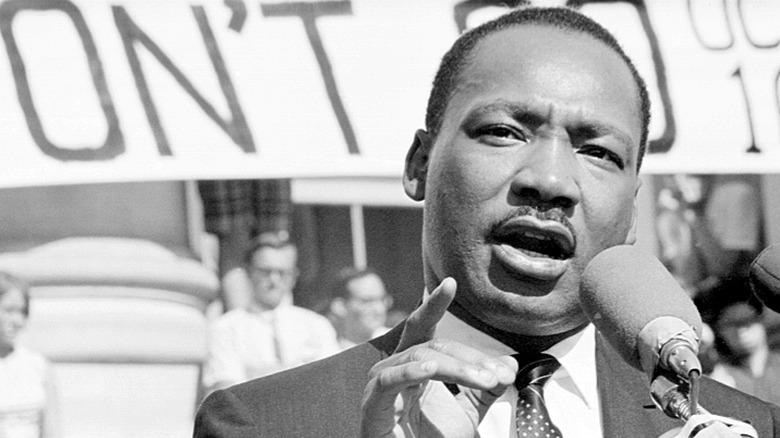

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day: Racists fought it tooth and nail

Civil Rights Movement leader and legendary activist Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is a revered figure. Calls for a national holiday in his honor began just days after his tragic assassination in 1968, and finally became reality in 1983. As explained by Historic America, the creation of the holiday was controversial because many still saw King as a disruptor and an agitator.

Federal law does not actually require states to observe national holidays, and many states resisted honoring King. In fact, shortly after the national holiday was established, Arizona governor Evan Mecham actually rescinded an existing state holiday honoring King. By 1989, only 44 states had actually adopted Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as an observed holiday.

Vox explains that the main reason behind the holdouts was simple racism. This was clear from some of the holidays that states did establish. Idaho, for example, created a Martin Luther King Jr.-Idaho Human Rights Day. Many Southern states played similar games, linking King's holiday to defeated Confederate General Robert E. Lee's birthday, for example, or establishing bland civil rights days instead.

The Undefeated explains that these shenanigans only stopped when the states in question began to feel an economic bite. For example, in 1991, Phoenix, Arizona lost out on hosting the Super Bowl to L.A. because of the issue, prompting the state to finally recognize the day in 1992. It took until 2000 for all 50 states to recognize Dr. King's holiday.

Presidents' Day: Problematic presidents

Like all national holidays — which every state can observe (or not) as it likes — Presidents' Day is a bit of a mess. ABC News explains that the holiday is officially all about George Washington, our first president and hero of the Revolutionary War. In fact, the holiday on the third Monday in February is officially called Washington's Birthday, but it's generally thought of as an all-purpose day honoring all 46 of our presidents — and many states have their own interpretations.

For example, She Knows notes that in some states, Presidents' Day is used to honor another president: Abraham Lincoln. Some honor Thomas Jefferson instead. And some states, like California, officially honor all our presidents. As the Seattle Times reports, 12 of our presidents owned slaves, and eight did so while in office. The Washington Post reports that our 10th president, John Tyler, was literally a traitor — he ended his political career being elected to the Confederate Congress (though he died before he could be seated).

In other words, many of the presidents being honored on Presidents' Day have some pretty problematic aspects. And yet, as the Christian Science Monitor notes, the president who did the most to abolish slavery, Abraham Lincoln, doesn't have a holiday to honor him and likely never will.

Memorial Day: Black history erased

Memorial Day is one of the most somber national holidays. It honors all of the brave people who lost their lives serving and defending their country. Not only do most people ignore that aspect of it in favor of celebrating a three-day weekend, but many don't know the true history of the holiday.

National Geographic explains that Memorial Day's roots go way back to the Civil War. Nearly half a million people died in that conflict, and after the war ended many white women in the South started a tradition of tending the graves of fallen soldiers, regardless of which side they'd fought for. But, as reported by Time, recently freed slaves began that practice the year before. Then, in May 1865, a group of freed slaves and some white missionaries staged a parade in Charleston, South Carolina to honor the Union Soldiers who died in the war, an act that many regard as the first Memorial Day.

As the Guardian Liberty Voice notes, the day wasn't yet referred to as Memorial Day — it was called Decoration Day in reference to the practice of decorating graves with flowers and other offerings. History explains that by 1890, every state observed the holiday, but it remained narrowly focused on the Civil War dead until World War I. It wasn't officially called Memorial Day until the Uniform Monday Holiday Act of 1968, and only became an official federal holiday in 1971, with no mention of the holiday's Black roots.

Juneteenth: Two years too long

Incredibly, many people in the U.S. weren't aware of the significance of June 19th until very recently. As PBS explains, that day is Juneteenth, which celebrates the day in 1865 when General Gordon Granger proclaimed all slaves in the state of Texas (the last state in the Confederacy to still have active slavery) to be free. For more than a century, the holiday was almost exclusively celebrated by the Black community, and, as NPR explains, despite the day being celebrated annually since then, it wasn't made an official federal holiday until 2021.

Still, that's progress, and of all the things to celebrate, the end of slavery should be at the top of the list. But celebrating Juneteenth as a day of freedom is perhaps too simple. The fact is, by June 1865 slaves in Texas had been technically free for more than two years, ever since Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. But, as The Undefeated explains, they were physically prevented from leaving plantations because their former owners simply ignored the proclamation.

The Washington Post reports that it wasn't just criminal landowners — Texas politicians also refused to enforce the executive order on the grounds that the state constitution forbid releasing slaves from their bondage. The day we celebrate as the end of slavery in the U.S. should be dated two years earlier than 1865, and Juneteenth acknowledged as a reminder of just how hard Americans worked to keep slavery in place.

Independence Day: Ignoring Black and Native Americans

Perhaps the most accurate description of Independence Day ever written is by filmmaker Richard Linklater, from his film "Dazed and Confused": "Don't forget what you're celebrating, and that's the fact that a bunch of slave-owning, aristocratic, white males didn't want to pay their taxes."

The popular narrative every kid learns in school is that the Fourth of July was a stirring act of courage in the face of tyranny. But the truth is that when Thomas Jefferson wrote "all men are created equal" in the Declaration of Independence, he wasn't referring to Black Americans, who were largely enslaved and would remain so for almost a century. Worse, as noted by US News, thousands of Blacks fought for the revolution believing independence from Great Britain would result in the end of slavery in the U.S., which we know didn't work out as they'd hoped.

Equally complex is how Indigenous Americans should feel about celebrating the creation of a nation that systematically murdered them and stole land they had occupied for centuries before the arrival of Europeans. As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, in the 19th century, the U.S. enacted laws designed to erase Native American ceremonial life. In response, many tribes began moving their traditional celebrations to the Fourth of July as a way to preserve those ceremonies. Ironically, that makes Independence Day meaningful for Indigenous people in spite of the horrifying racism they faced.

Labor Day: Born from violence

For most people, Labor Day is just a three-day weekend marking the end of the summer party season. Or a great shopping opportunity for back-to-school stuff for the kids. But behind the cookouts and final swims there's a violent, radical past that most of us either don't know about, or just take for granted.

The Conversation reports that in the early 19th century, workers in the U.S. manufacturing sector routinely put in 70-hour work weeks (or more), usually under miserable conditions. Half a century later, there had been some minor improvements, but laborers were still poorly treated and overworked. The labor movement had formed unions, but they were weak and divided. There were frequent violent clashes between workers and the wealthy folks who owned the factories and mines and, well, everything else.

Labor Day was originally designed to unite the unions and to push for things we now take for granted, like the eight-hour work day and the weekend, which practically didn't exist as a concept back then. Teen Vogue explains that the Pullman Strike in 1894 — which paralyzed the nation and ended in chaos and violence when federal troops were sent in to break it — inspired president Grover Cleveland to create the Labor Day holiday as a conciliatory gesture. When we fire up the grill on the first Monday in September each year, we should remember that people literally died for our weekends.

Columbus Day: A legacy of death and disease

By now most people know that the previously widely accepted story of Christopher Columbus discovering America isn't exactly accurate. While Columbus' voyage in 1492 was a huge achievement, even if he failed in his actual purpose of finding a trade route to China, the damage and destruction he inflicted on the New World and the people who lived there is astronomical.

History explains that Columbus heralded an age of increasing slavery by casually enslaving many of the Indigenous people he and his crew encountered — in fact, he enslaved six people on his first day in the New World. When people tried to resist the cruel governance that Columbus imposed, he responded with brutal crackdowns. The Devil's Advocate points out that Columbus and his crew spread numerous diseases to the native people they encountered, resulting in millions of deaths and the weakening of entire cultures. It's no wonder that every year Columbus Day is greeted with worldwide protest and dissent (via BBC News).

The holiday's more recent racist past is also often forgotten. The Washington Post reports that in the late 19th and early 20th century, Italian immigrants to the U.S. were seen as dangerous foreigners, and that Columbus Day was initially seen as a way to reposition Italian explorers as American pioneers while putting on public displays of Italian-American patriotism. In other words, if the U.S. had been a little less racist, we might not have Columbus Day at all.

Veterans Day: Woefully insufficient

Throughout history, holidays have often served as superficial gestures, and Veteran's Day is a great example. Our veterans have made incredible sacrifices serving their country — often the ultimate sacrifice. But setting aside one whole day a year as Veterans Day serves mostly as a reminder that we treat our vets pretty poorly the other 364 days a year.

The Atlantic explains that the vast majority of Americans have little connection to their country's military forces — only about 1.5 million people are on active military duty, with another 850,000 or so in the reserves. As such, Veterans Day and other public displays of support for military service personnel can be pretty empty and vacuous.

Worse than the empty spectacle is how we treat our veterans on the days that aren't national holidays. USA Today reports that just about every Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital in the country sports longer wait times and higher incidences of infections and bed sores than non-VA care facilities. And a 2015 Rolling Stone notes that unemployment is a constant problem for our veterans, about half of whom were unemployed at the time of writing. This is also tied to why veterans make up about a third of our country's homeless population. There is also likely a connection between these statistics and disproportionately high level of post-traumatic stress disorder suffered by veterans. Setting aside one day a year to say thank veterans for their service isn't nearly enough.

Thanksgiving Day: The true history is bloody and violent

Right up there with Columbus Day, Thanksgiving is a U.S. national holidays that has been (literally) whitewashed. The version of events we learn in school is almost completely divorced from reality. In fact, as noted by Insider, there's even a movement to cancel the holiday altogether due to its bloody, violent reality.

The myth behind Thanksgiving is that kindly members of the Wampanoag tribe saw white settlers from the Plymouth Colony struggling and opted to share their food in a gesture of community.Smithsonian Magazine explains that not only were the motivations of the Wampanoags more complex (they hoped an alliance with the newcomers would insulate them from a rival tribe), but the move backfired big time as the colonists systematically took Wampanoag land and spread diseases to them. There was eventually a devastating war between the English settlers and the Indigenous Americans that left the Wampanoag in ruins.

The war was incredibly violent. Towns were burned to the ground, and according to historian Robert E. Cray, Jr. nearly half of the Native American population in the area died as a result of the conflict, along with about 30% of the English population. Today, the Wampanoag tribe views Thanksgiving Day as a day of mourning — that's the true significance of Thanksgiving.

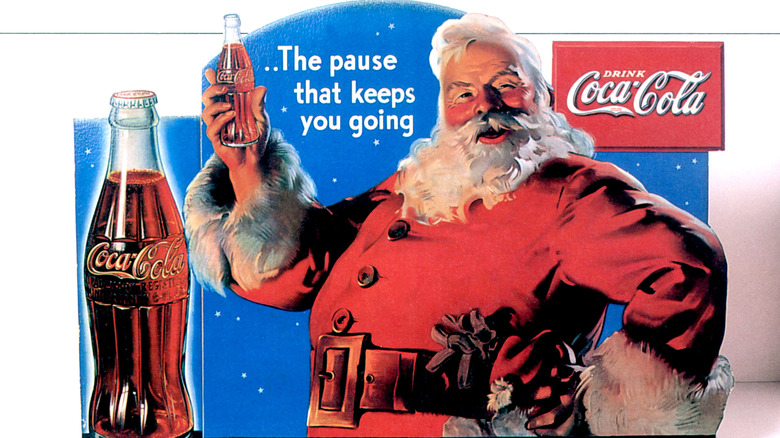

Christmas Day: It's all about money

Putting aside the fact that it's odd for a secular country to pick just one religious holiday to make official, Christmas has in almost every way transcended its Christian origins. In the modern day, it's essentially a holiday dedicated to capitalism and shopping.

But this isn't a new development. The Toledo Blade notes that prior to the mid-19th century, Christmas celebrations were dominated by "Puritan fustiness," which resisted any sort of pomp, and that many Christians didn't celebrate it at all, because it's not mentioned specifically in the Bible. Later, according to the Financial Times, Christmas became a chaotic affair with drunks reeling in the streets, sparking an effort to redefine the holiday as a family affair focused on the home.

Futurity reports that in the 1800s, retail stores began to exploit the holiday for purely profit-based reasons. This was also when secular imagery like the Christmas tree and Santa Claus became prevalent, as did worries that Christmas was becoming too commercial. By the 1960s, "Peanuts" was complaining about the impact of capitalism on Christmas. Cut to the 21st century and, according to Reuters, even the Pope is concerned about it. Christmas was once a deeply religious holiday for a specific group of people, but today it might as well be called Capitalism Day.