The Untold Truth Of The Lighthouse Of Alexandria

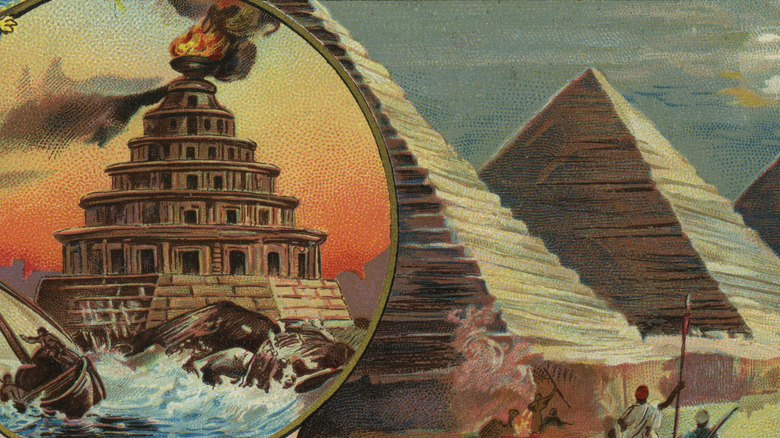

One of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Lighthouse of Alexandria existed for over 1,000 years. During its lifetime, it stood towering over the port of Alexandria and although it wasn't always a lighthouse, its legacy as such persists.

In its time, the Lighthouse of Alexandria was one of the tallest manmade structures on the planet and many claimed that it could be seen from miles away, even on land. But because few contemporary accounts exist of the lighthouse, much of what we know about it is constructed from fragments that historians left behind during the waning years of the structure. But what happened to the lighthouse that made it join five other wonders in disappearing from the face of the earth?

It's possible that a modern-day Lighthouse of Alexandria may be on the horizon. In addition to plans to conserve the remains of the original lighthouse, plans have been proposed to build a replica of the once majestic wonder. But can it truly rival that which existed in antiquity? This is the untold truth of the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

Who built the Lighthouse of Alexandria?

Built around 300 BCE, it's believed that the architect Sostratus of Cnidus constructed the Lighthouse of Alexandria, also known as the Pharos of Alexandria. But according to the World History Encyclopedia, it's possible that he was merely the financial backer for the project. The lighthouse was commissioned by Ptolemy I Soter around 297 BCE and was completed roughly 20 years later by his son Ptolemy II. However, the exact dates for the start and finish of the construction are unknown and various sources offer differing dates.

The Roman author Gaius Plinius Secundus, also known as Pliny the Elder, wrote that King Ptolemy's "generous spirit" allowed Sostratus to inscribe his name into the building. Sostratus reportedly carved onto the lighthouse "Sostratus of Cnidos, the son of Dexiphanes, to the Divine Saviors, for the sake of them that sail at sea," per The University of Chicago.

Although "Divine Saviors" can be interpreted to refer to Ptolemy I and his wife or his son, it might also refer to Castor and Pollux, Greek gods who were "saviors of sailors." It's also possible that the dedication refers to Zeus himself, since a statue of Zeus was said to stand atop the lighthouse. But some accounts claim that Poseidon rested atop the lighthouse instead.

Where was the lighthouse located?

The lighthouse was built near the harbor of Alexandria, Egypt on the island of Pharos. Greek historian Strabo, who visited Alexandria around 24 BCE, according to The University of Chicago, wrote that the lighthouse was built because the coast had reefs and shallows and was low on both sides, and so "those who were sailing from the open sea thither needed some lofty and conspicuous sign to enable them to direct their course aright to the entrance of the harbor."

But the World History Encyclopedia writes that the lighthouse served more than just a functional purpose. It's believed that Ptolemy I commissioned the lighthouse in order to remind everyone of his power even after he was gone. And considering that after the pyramids of Giza, the Lighthouse of Alexandria is thought to have been the "tallest structure in the world built by human hands" at the time, the lighthouse likely served both of its purposes.

What did the Lighthouse of Alexandria look like?

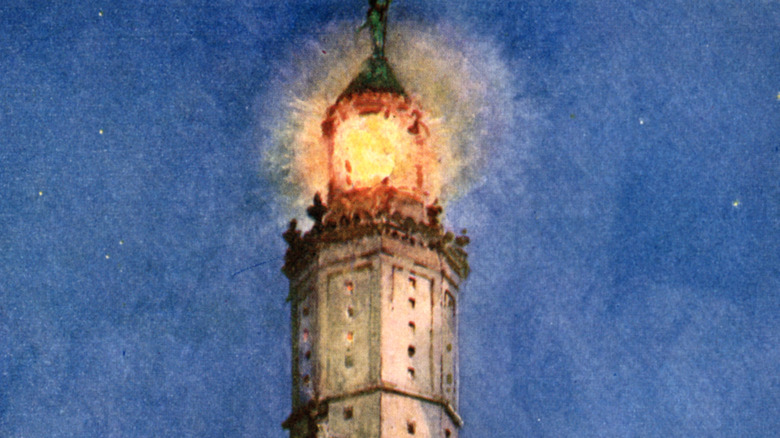

Unfortunately, no one knows exactly what the Lighthouse of Alexandria looked like. The descriptions from most ancient writers are "vague, confusing, and conflicting," according to the World History Encyclopedia. But overall, most sources agree that the lighthouse had three floors and was white.

Hellenistic Alexandria writes that in 1909, Hermann Thiersch offered a reconstruction of the building's architecture, showing the different shapes of the three levels. The first level was a cuboid, the second level was octagonal, and the third level was circular. Overall, it's believed that the lighthouse's total height was between 350-450ft high. The lowest section reportedly held the stables and government offices. The octagonal section was for tourists and offered a view from the balcony, and the top section is where the light would reside, according to ThoughtCo.

Most of the "substantial descriptions" come from Arab historians like Al-Mas'udi, Al-Gharnati, and Al-Idrisi. Al-Balawi also described the lighthouse as having a long ramp that spiraled clockwise, "wide enough for two pack animals to pass." And in 1182 or 1183, Ibn Jubayr wrote that the Lighthouse of Alexandria "can be seen for more than 70 miles, and is of great antiquity. It is most strongly built in all directions and competes with the skies in height. Description of it falls short, the eyes fail to comprehend it, and words are inadequate, so vast is the spectacle."

How did the light work?

The Lighthouse of Alexandria may not have originally been a lighthouse. Some of the earliest accounts of Pharos "make no mention at all of a light," according to the World History Encyclopedia. And despite the descriptions of the inside of the lighthouse, "there are no sources referring to the mechanism to the top that emitted light," writes Hellenistic Alexandria.

At some point, it's believed that a light was added to the top of the lighthouse and was most likely kept alight with oil rather than wood since wood was difficult to come by. But the earliest mentions of the flame come in the 1st century CE, from Pliny the Elder. According to The University of Chicago, Al-Masudi, in 944 CE, referred to a mirror at the top of the lighthouse, which is thought to have reflected the light across greater distances and could've also reflected the sun. Al-Gharnati also mentioned a mirror, writing that the mirror "was moved to reflect the setting sun and set [ships] afire while still at sea."

The lighthouse may have also housed a telescope at the top. In the 9th century, Ibn Khordadhbeh wrote that one could see as far as Constantinople in the telescope.

One of the Seven Wonders of the World

As early as the fourth century BCE, historians and geographers started compiling lists of spectacular sights in the world. World History Encyclopedia writes that Herodotus, Philo of Byzantium, and Callimachus of Cyrene all created shortlists of sights to see. But since the Colossus of Rome and the Lighthouse of Alexandria are the last two "accepted into the canon," it's believed that the list we regard today as the "official" list of the Seven Wonders of the World was created around the second century BCE.

The Seven Wonders of the World are as follow: the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Colossus of Rhodes, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

But according to "The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World" by Peter A Clayton and Martin Price, the Seven Wonders existed simultaneously for only about 50 years.

In 226 BCE, the Colossus of Rhodes was brought down by an earthquake and although the Rhodians wanted to reconstruct it, it ended up remaining a pile of broken bronze, and the Seven Wonders of the World never stood at the same time ever again. By the time the list of the Seven Wonders of the World became "crystallized" during the Renaissance, few of the wonders remained.

Influences of the lighthouse

In addition to being lauded as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Lighthouse of Alexandria has a lasting architectural and linguistic legacy. The World History Encyclopedia writes that the architectural design of the Lighthouse of Alexandria was copied in other harbors in the ancient world, although none were as tall as the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

According to Renewal of the memory of Pharos by Abir Abd-El Mohsen Kassem, the Lighthouse of Alexandria was also depicted on numerous mosaics, murals, and coins. An ancient tomb in Abusir is also believed to be a small-scale version of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Historians have also suggested that the Lighthouse of Alexandria influenced Arabic minaret architecture. However, according to The University of Chicago, the first minaret that appeared to resemble the design of the lighthouse wasn't constructed until 1304. By that point, the Lighthouse of Alexandria would've been largely in disrepair. As a result, it's believed that minaret architecture was instead "derived from the Syrian church tower."

In the end, the Lighthouse of Alexandria was so influential that "pharos" started being used to refer to any tall tower that was used to help guild ships. And in several modern languages, such the Romance languages, the word for lighthouse is derived from the word pharos.

Damaged by numerous earthquakes

Over the course of 1,500 years, the Lighthouse of Alexandria withstood numerous earthquakes. The University of Chicago writes that one of the first earthquakes that dismantled the lighthouse occurred in 796 CE, and left only the first level standing. By 875 CE, a "wooden cupola" was built on the top of the lighthouse, so it's believed that by that point, the lighthouse was used as a watchtower instead.

Earthquakes in 950 and 955 CE also brought down parts of the lighthouse, but those in 1303 and 1323 CE were responsible for some of the worst damage. By the time Ibn Battuta traveled to Alexandria in 1326, what remained of the first level was "partly in ruins" and by 1349, the lighthouse was "in such a state of ruin that [it] was impossible to enter." An earthquake in 1375 is believed to have finally reduced the lighthouse to rubble. But according to the World History Encyclopedia, the Lighthouse of Alexandria was given "regular repairs and extension" in its lifetime, including the addition of a domed mosque to the top part around 1000 CE.

Between 1477 and 1479 CE, the remaining stones of the lighthouse were used by Sultan Abu Al-Nasr Sayf ad-Din Al-Ashraf Qaitbay to build the Qait Bey Fort on Pharos, also known as the Citadel of Qaitbay. According to Alexandria, the fort was part of Sultan Qaitbay's coastal defenses against the Ottomans.

Just under the water

In 1916, French engineer Gaston Jondet undertook an archeological study of the submerged port at Pharos, during which he discovered the remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Jondet is even believed to have pioneered the "archeological study of submerged port facilities." According to Underwater Archaeology in Egypt by Emad Khalil and Mohamed Mustafa, this was the first time that "such gigantic submerged structures" were discovered. Some of the remains could even be seen with the naked eye, since they were less than 30 feet underwater.

Over the years a few more archeological discoveries were made near Alexandria. In 1933, Prince Omar Tousson funded research to recover a marble head of Alexander the Great after a British Royal Air Force pilot noticed submerged ruins from his plane. And in 1961, amateur archeologist and professional diver Kamel Abu El-Saadat found fragments of a large sculpture over 20 feet tall, Victor V. Lebedinsky writes in "Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century." The following year, the sculpture was pulled out of the water and inspired a UNESCO grant to look for more archeological fragments in the seabed.

The UNESCO-sponsored expedition

In 1968, Abu El-Saadat was given a grant from UNESCO to describe the architectural fragments in the seabed, with a focus on what could potentially be a fragment of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Honor Frost and Vladimir Nesterov were also invited by the Egyptian government, and together the three of them compiled a list of 17 different fragments of the Pharos lighthouse in the seabed, according to Underwater Archaeology in Egypt. However, Frost noted that if they were to do a complete survey, the number would be "multiplied a hundred-fold."

According to UNESCO, due to the War of Attrition between Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Palestine, the coastal area around Alexandria was made "a military zone" and archeological investigations had to be put on hold. But despite the delay, the report by Abu El-Saadat, Frost, and Nesterov "laid the groundwork for later excavations of the sites."

However, before those excavations could start, sea erosion of the Qait Bey Fort began to threaten the remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria, though it was technically an attempt to keep the erosion at bay that threatened the archeological remains.

Finding the lighthouse underwater

In the early 1990s, in an effort to protect the Qait Bey Fort from sea erosion, 180 cement blocks were put along the perimeter of the fort along the seabed. Unfortunately, these cement blocks were essentially put right on top of what remained of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Focus on Alexandria writes that no one would've even realized that one heritage site was being saved "at the expense of another" had there not been a film crew there who happened to be shooting underwater.

According to UNESCO, once this was realized, the public outcry led to the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities and UNESCO coming with a plan in 1997 to protect both the fort and what remained of the lighthouse. Global Construction Review also writes that UNESCO sponsored a series of surveys of the sea floor, which found that there were at least 2,500 pieces of stone fragments across an area of six acres.

Unfortunately, cement blocks weren't the only thing threatening the remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. The bay next to Alexandria is heavily polluted, which accelerates erosion. In 1998 and 1999, UNESCO organized the International Hydrological Program to "evaluate the situation" and come up with recommendations.

An underwater museum

In the late 1990s, an underwater museum was proposed so that the public could witness the sunken remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. According to Smithsonian Magazine, although the plan was put on hold in 2011 after the Egyptian revolution, plans were revived in 2015. It's believed that by making the site a museum, and even a potential World Heritage site, the remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria can be protected and monitored against pollution and poachers. In 2020, Egypt's parliament also ratified a bill that would impose a fine of $63,850 on anyone who "acquires or sells an antiquity or part of it outside Egypt" in an effort to dissuade archeological poachers. There was also the hope that the museum could help revive tourism in Alexandria in addition to providing for the opportunity for further research on the archeological remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria and other sunken remains.

Unfortunately, Al-Monitor writes that poor resources have prevented the implementation of the underwater museum for years. However, in 2021, Alexandra University announced a new project titled Underwater Heritage, which hopes to excavate underwater artifacts around the eastern port of Alexandria.

Will the lighthouse ever be reconstructed?

Almost 600 years after the Lighthouse of Alexandria fell, plans have been put forward to reconstruct the Seventh Wonder of the World. Open Democracy writes that the plan was actually first proposed in 1978, when diplomat Omar al-Hadidi suggested rebuilding the lighthouse to Governor Fouad Helmy.

By 1997, up to 32 companies were competing for the project of rebuilding the Lighthouse of Alexandria, but some of their propositions seemed to push the lighthouse too far into modernity. Some of the plans included a shopping mall in the lighthouse, while others proposed "laser beams at the top instead of the traditional lantern." In response, Governor Mohamed Mahgoub cancelled the project altogether.

But in 2005, the plan was once again revived as "part of a series of projects toward a vision to develop the east harbor." And according to the BBC, plans were approved in 2015 to rebuild the Lighthouse of Alexandria just a few feet from where it originally stood. As of 2021, it appears as though the replica has yet to be constructed.