The Untold Truth Of The Temple Of Artemis

The Temple of Artemis was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. If that were all you know about this place, it would be pretty easy to imagine it as something huge and magnificent and grand. The type of thing that stands up to the Great Pyramids of Giza.

But the unfortunate truth is that the Temple of Artemis (or the Artemisium, if you prefer) really isn't all that spectacular. If you took a visit to the site of the temple in Turkey today, all you'd be greeted with would be a single column — one that's far from undamaged, and which is actually a stack of column pieces unearthed over the years. There's not really all that much there anymore.

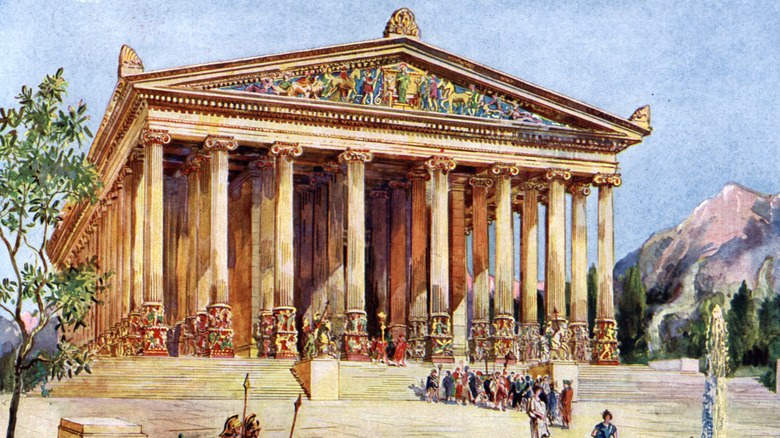

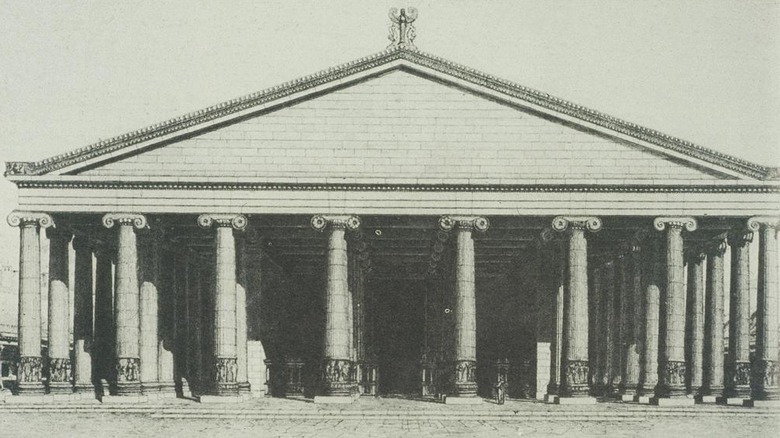

But the Temple of Artemis wasn't always like that. In the past, before the temple was reduced to ruins, it was a massive work of Greek architecture — complete with huge carvings and larger even than the Parthenon in Athens — and arguably the most incredible of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. What happened to it, though? Well, a lot of stuff can happen in two and a half millennia, and indeed a lot did happen to the Temple of Artemis between the 6th century B.C. and now. Here's the untold truth of the Temple of Artemis.

This is a temple to a different Artemis

You're probably at least a little familiar with the Greek goddess Artemis. You know, the virgin goddess of the hunt, forests, animals, and the like, per the World History Encyclopedia. That's generally what most people probably think of when the name Artemis comes up, and so it would make sense that this is a temple to that goddess.

Strangely enough, though, that's not really true. Or, at least, not entirely. Even though it was founded by Greeks, Ephesus was located in Asia Minor, specifically in what's now modern-day Turkey, according to ThoughtCo. Being where it was, Ephesus saw its fair share of Eastern influence seeping in and mixing with the Greek, creating a very different version of Artemis.

Unlike in classical Greek mythology, the Ephesians believed both Artemis and Apollo to have been born in a grove called Ortygia. Finding a place near their city with that same name, they claimed it to be the birthplace of the two gods, per University of Warwick. (The most familiar form of Greek mythology names Delos as the birthplace). On top of that, the Ephesians associated Artemis really heavily with fertility, depicting her in statues with eggs or breasts covering her torso, and her legs held tightly together by a fitted skirt. There's a chance that, in Ephesus, Artemis was conflated with another local goddess of fertility, named Cybele, which kind of explains where these changes might have come from.

The Temple of Artemis might be older than we think

If you were to look up pictures of the Temple of Artemis, you might find some conceptual art featuring the exact sort of classical Greek temple you'd imagine. You know, white marble, exquisite columns, carvings of mythological heroes — essentially the Parthenon, in short. Well, you'd get either that, or what it looks like in the 21st century: a single column, pieced together from uncovered remains.

But the Temple of Artemis might have looked pretty different. Or, the very first one might have, at least.

Legend has it that, before the building of the magnificent Temple of Artemis in the 6th century B.C., another temple stood in the same area. Unfortunately, there isn't much information out there about it. It's hard to say when this fabled temple was actually built, but, per the University of Warwick, it might have been destroyed around the 7th century B.C. in a flood. As for what this site was, well, it might have been some sort of Bronze Age religious site constructed before major Ionian immigration into the area. That said, it's hard to know for sure.

If nothing else, the Ephesians seemed to believe that there had been some sort of temple there. According to the World History Encyclopedia, stories say that the Ephesians would tie long ropes from the old temple site to their city, hoping that Artemis would see their dedication to her and protect them in wartime.

The Amazons were associated with the Temple of Artemis

One of the more fun versions of the founding of Ephesus and the first incarnation of the Temple of Artemis takes a little bit of a dip into mythology by pulling the Amazons into this whole tale.

The Amazons were a group entirely made up of warrior women and descended from the Greek god of war, Ares, per World History Edu. As for where the Amazons cross over with the Temple of Artemis, well, in Greek mythology, they founded it. The when is a little hazy; some accounts say it was created by their first queen, Otrera, while others claim that it was completed around the same time that they had a less-than-favorable encounter with Theseus (via Theoi Project).

Either way, though, they would worship Artemis at this temple, making music and dancing while wearing their armor and weapons — not taking part could supposedly end in divine punishment. Aside from worship, they also came to use the temple as a sanctuary on at least a couple occasions. One of those times likely came when the god of wine, Dionysus, overwhelmed and killed many of them in a battle (which technically started at Ephesus but ended elsewhere). The other involves one of the Twelve Labors of Heracles. Specifically, when Heracles was sent to retrieve the girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyta, which ended in bloodshed (at least, in certain accounts). Needing a sanctuary makes a lot of sense, in that case.

The Temple of Artemis was funded by a Lydian king

Per the World History Encyclopedia, the funds for the Temple of Artemis came from the Lydian king Croesus, who managed to conquer Ephesus somewhere between 550 and 560 B.C. (his name was even found on a piece of a column, saying that it was "dedicated by Croesus"). With that funding, construction on the temple got underway pretty quickly, overseen by the architect Chersiphron (and, maybe, his son Metagenes, depending on whose report you're reading).

Construction wasn't quick by any means — the temple wouldn't be completed for another 120 years — but the finished project was an architectural marvel. The first temple made entirely out of marble (via UChicago), the Temple of Artemis was massive, dwarfing the famous Athenian Parthenon at 425 feet long and 225 feet wide and lined by 127 intricately carved columns.

Aside from the artistic beauty of the temple, there was also a bit of thought put into the engineering of the building. Its foundations were laid in a marshy area and were made of layers of charcoal and sheepskin, meant to protect the temple from earthquakes and support its weight, respectively.

An arsonist burned down the Temple of Artemis

"All press is good press" is a phrase that you've probably heard at some point, and one that's usually connected to less-than-stellar sorts of situations. While there's no doubt that the phrase brings to mind plenty of modern events, it's also the reason that the Temple of Artemis burned down.

On July 21, 356 B.C., a man by the name of Herostratus entered the Temple of Artemis and decided to set it aflame. By the next morning, the whole thing was reduced to charred bits of rubble (via Amusing Planet). According to History Today, he didn't even try to flee, just letting himself be caught and tortured.

Here, it would be nice to take a step back and see who Herostratus was, but that's not really possible. His upbringing is essentially a mystery — he might have been a low-born Ephesian or a slave, but that's all we can guess. He is just known for this act of arson, which is exactly what he wanted. He admitted under torture that he'd burned the temple just to be known as "that guy who burned the Temple of Artemis." For that, the Ephesians executed him and banned his name from being mentioned, trying to deny him his ambitions.

Unfortunately for them, though, we clearly know Herostratus' name. Theopompus and Strabo named him as the arsonist, and he's lived on in infamy ever since.

The weird connection between the Temple of Artemis and Alexander the Great

On the surface, it would seem like the only major connection between the Temple of Artemis and Alexander the Great is that they vaguely have to do with ancient Greece, but, in actuality, the connection goes quite a bit deeper than that. And it starts with dates — specifically, with July 21, 356 B.C.

That's the day that the Temple of Artemis burned down, but it's also the same day that Alexander the Great was born. And so, fittingly, there's a legend to link them. The story goes that the only reason the Temple of Artemis burned down was because Artemis herself wasn't home; she was over in Macedonia, assisting with the birth of Alexander the Great (via the World History Encyclopedia). That said, not everyone in Ephesus was so pleased with that interpretation. According to Plutarch, Hegesias of Magnesia proposed the idea as a joke, but some of his peers saw the arson as a sign of calamity to come.

The connections don't quite end there, though. As explained by UChicago, Alexander himself arrived in Ephesus in 334 B.C. while the Temple was being rebuilt. Seeing that, he offered to pay for all the expenses on the Temple, asking that he be credited with an inscription in the final product. The Ephesians turned him down, though, tactfully saying that it was "inappropriate for a god to dedicate offerings to gods."

The second Temple of Artemis is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

After the Temple of Artemis burned down in 356 B.C., that was far from the end for it. Nope, not even close. Reconstruction of the temple began, paid for by the people of Ephesus, who collected their own jewelry to provide the funds (via the World History Encyclopedia). This new, Hellenistic version of the temple followed the same design as its predecessor, even if it was just a little smaller.

That said, with the original being as massive as it was (and built right by the sea, which was a nice plus), the slight downgrade was still a final product that was plenty grand — one worthy of being included on Herodotus' list of the Seven Wonders of the World (via History Today). Pilgrims travelled to the temple from all around the Mediterranean world, writing about their experiences seeing it up close. Sometime around 140 B.C., Antipater of Sidon was one of those pilgrims, writing that he'd already seen many of the other Wonders of the Ancient World — the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the statue of Zeus, the pyramids, and the like. But the Temple of Artemis overshadowed them all, and he believed that "apart from Olympus, the sun has never looked upon aught so grand" (via the University of Warwick). Quite the glowing review.

The Temple of Artemis was a big part of the financials of Ephesus

With the Temple of Artemis being as big and famous as it was, it pulled in plenty of visitors to Ephesus. Maybe a little more than plenty.

Pilgrims from all over the Mediterranean flocked to Ephesus in order to lay their eyes on the magnificent sight that was the Temple of Artemis, and with them came a ton of offerings, often in the form of jewelry or money (via History Today). But some of that economic prosperity also came from the fact that people were willing to buy dedications for visitors to go and see the temple — just another thing that the city was able to cash in on (via the University of Warwick). Funnily enough, the high number of pilgrims also spread worship of this particular version of Artemis out past the borders of Ephesus.

Weirdly, though, the temple became so closely intertwined with the economy of the city that it became more than a place of religious worship; it became a bank. According to the Financial Times, the Artemisium was an especially long-standing bank, serving wealthy clients from all across the Greek world and beyond, and respected by generations of rulers. People could deposit their valuables and trust that the Temple of Artemis being, well, a temple would keep their treasures safe since the gods themselves would see to it that their property was in good hands.

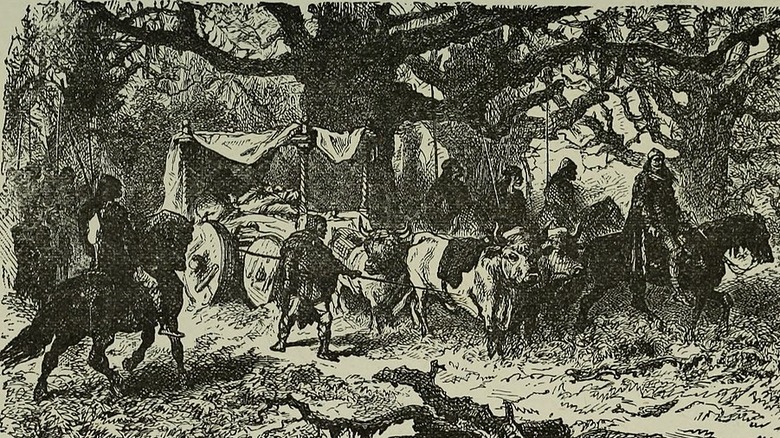

The Goths ransacked the Temple of Artemis

The history of the Goths, is, well, an entire story on its own, and one that can't fully fit here. But here are the basics.

There really isn't a whole lot known about the origins of the Goths; as explained by Live Science, as best we can tell, they might have originated up near Scandinavia before traveling south and having a series of run-ins with the Roman Empire. Although, "run-ins" might be putting it lightly. The Romans actually referred to them as barbarians, and the history between the two groups was contentious at best, marked with raids and conflict across multiple centuries. And the Goths were the ones to sack Rome in the 5th century, so, you know, there's also that.

This tumultuous relationship with Rome is where Greece comes into the picture, seeing as how, at the time, Greece was under the rule of the Romans. The Goths started leading invasions into Greece during the middle of the 3rd century, only to be met by Roman forces in battle (one of which took place in Thermopylae, which might sound familiar if you've heard of the 300). One of those invasions eventually went after Ephesus, which, under the Romans, had become the capital of that region, according to the World History Encyclopedia. In that particular campaign in 267 A.D., the Goths also attacked the Temple of Artemis, most likely destroying it (or at least, plundering it). From there, things were set to really go south.

Christianity destroyed the Temple of Artemis

Okay, so it might sound a little strange to say that Chrisitianity destroyed a physical temple, but there's a reason here. (Or maybe it doesn't sound strange at all, given the number of wars waged over religion, but that's a topic for another day).

Here's how it unfolded. Greece was, essentially, absorbed into the Roman Empire, but despite Roman mythology pretty closely matching its Greek counterpart, Christianity eventually seeped its way in. Per the World History Encyclopedia, the Roman emperor Theodosius I was kind of at the root of this whole debacle, issuing a decree condemning pagan practices (and officially closing the temple).

According to UChicago, various writings cropped up, including a story of the apostle John arriving at Ephesus, at which point the Temple of Artemis fell into spontaneous ruin — the altar broke apart, as did the images of the Greek gods, and the roof caved in. Supposedly, Artemis left her temple and gave it to Christ, the people seeing no purpose in worshipping her anymore.

As for the fate of the physical temple, we have John Chrysostom to thank for that. An archbishop in Constantinople in the late 4th century, Chrysostom is credited with the destruction of the Temple of Artemis, leading a Christian mob to destroy it completely in 401 A.D. Ironically enough, though, a teacher of his was known for speaking openly against the destruction of these temples. Too bad his student didn't seem to agree.

The Temple of Artemis was left in disrepair

Taken altogether, the Temple of Artemis has a pretty storied history, getting destroyed and rebuilt time and time again.

But, in the end, its grandeur and influence were left to peter out. After the attacks on it in the 3rd and 4th centuries, the temple was never fully restored; instead, per UChicago, its ruins were repurposed into a quarry. This awe-inspiring temple became part of a building project for a new Byzantine city in Ephesus.

There's a pretty decent chance that the temple building was essentially gutted for its parts. According to the World History Encyclopedia, it was a fairly common practice in Ephesus for parts of older buildings to be taken and reused in the construction of newer buildings. Alternatively, its bricks might have been burned for lime. The more fun story, though, comes from the rumor that a few of its columns were used in the construction of the Hagia Sophia — where those eight green columns have stood for centuries after the fall of the original temple (per Wild Hunt).

As for the rest of the ruins, earthquakes did their number on the structure (despite all the precautions taken for that exact purpose), and flooding buried much of the rest in silt. Only pieces were discovered years later, which were stacked into the composite column that we see today.