The Untold Truth Of The Seven Wonders Of The Ancient World

It may seem like the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is a list that's so set in stone it has never changed. But, the truth is more complex than that. This list of wondrous and awe-inspiring sights from around the Mediterranean region is plenty cool, but its development involved lots of debate and competing lists. If you were somehow able to talk with the 6th century Gregory, Bishop of Tours, for instance, he might be a tad horrified to learn that your list didn't include any biblical achievements like Noah's ark (via "The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World").

What's more, the details of the wonders that did make it into the list may surprise you. There's more than one spectacular tomb on the list, for one, and some of the dimensions of the other features can still surprise modern folks. This is the untold truth of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

It all started as an ancient tourist guide

Though it may now seem like a grand concept, the first known lists of the seven wonders may be more accurately interpreted as travel guides. Sure, the travelers in question would have to be pretty determined and also a bit rich to make their way around the ancient Mediterranean world, but they would have been sightseers regardless.

The sights in question were often framed as themata, per "The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World." Themata can be pretty prosaically translated as the Greek for "things to be seen," as opposed to the more nebulous thaumata, meaning "wonders." These really were sights to be gawked at, not necessarily meant to inspire wonder in a more spiritual or at least less defined way (though worshippers at some of the religious sites included in the list may have begged to differ).

And who was writing these guides? According to the World History Encyclopedia, one of the first known themata-listers was Philo of Byzantium in the 3rd century B.C. The BBC's History Extra also notes that the 2nd century B.C. Anipater of Sidon also made his own list. Plenty of others got in on the game, too, including the Greek writer Herodotus, who is often referred to as one of the first historians in, well, history (via World History Encyclopedia).

There's a reason there are seven wonders

Seven seems like a bit of a strange number to some people. First of all, quite a few humans defaulted to a base-10 numbering system in the ancient world, almost certainly because we have a total of 10 digits on both of our hands combined (via ThoughtCo). But, unless an ancient counter had a series of accidents with ancient construction equipment and was missing a few of those fingers, using an odd number like seven doesn't immediately make sense.

But, there was an apparent logic to choosing seven wonders, which multiple list makers did over and over across the centuries. History Extra reports that the Ancient Greeks believed that seven was a spiritually significant number, perhaps because it included the five known planets, along with the sun and moon. "The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World" has a more practical explanation, pointing out the idea that seven seems just long enough without inviting too much inane subdividing or arguments about ranking the wonders. Ancient people, perhaps, were just as much prone to ranking and unasked-for hot takes as their modern descendants.

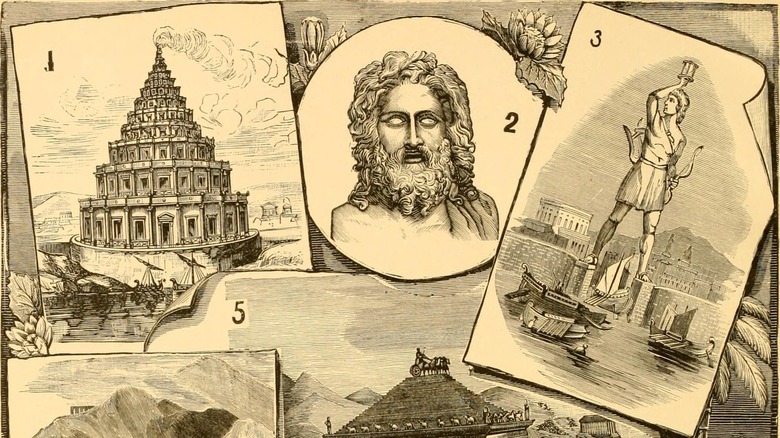

No one's sure that all seven actually existed

For modern people, one of the most frustrating aspects of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is that nearly all of them have disappeared. It's no longer possible for us to visit the Lighthouse of Alexandria or gawp at the towering height and shining skin of the Colossus of Rhodes. To be fair, as Britannica notes, you could visit some submerged ruins near Alexandria, Egypt that may have come from the earthquake-toppled lighthouse. But swimming around some murky stone blocks just isn't the same as climbing to the top of an ancient tower and lighting its flame.

As if that weren't enough of a bummer, some of the more fantastical seven wonders, like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, didn't leave behind many records at all. In fact, modern researchers are pretty skeptical that some of the wonders ever existed at all, per ABC News. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon have come under particular fire because even the record-happy Babylonians don't seem to have documented it anywhere.

Likewise, the differing accounts of the Greek Colossus of Rhodes make it tough for modern scholars to believe it was ever real. Was the reportedly humongous bronze statue even possible to construct in the 3rd century B.C.? And why doesn't anyone agree whether it stood astride the city's harbor or off to one side? It's all a bit much for some skeptical researchers (via National Geographic).

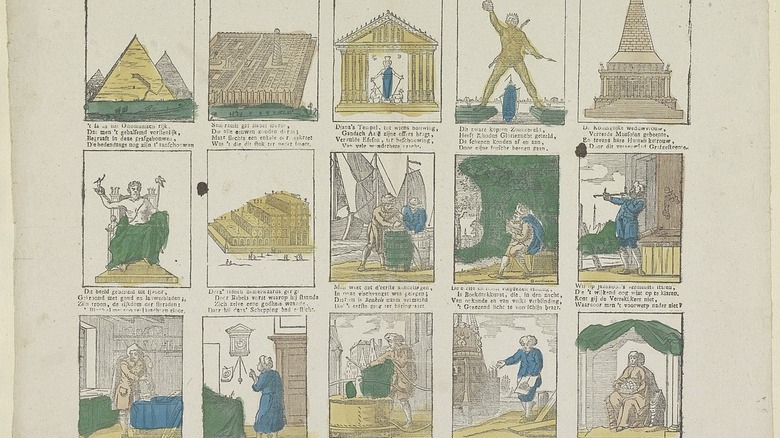

People didn't always agree on what should make the list

There were actually multiple lists of wonders circulating around the ancient world, written by multiple authors and based on personal opinion, as the BBC's History Extra notes. Naturally enough, these lists were also restricted to where their writers (or their sources) were able to travel. Add in a few editorial judgments and an accident of history here or there, and we've got the "canonical" Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

But, if you restrict yourself just to those core seven sights, you're really going to miss out. Some of the features that didn't make it to the familiar list of ancient wonders seem pretty worthy of inclusion in their own right. They're at least as interesting as giant statues and grandiose mausoleums. History Extra mentions Babylon's famed Ishtar Gate, a grandly decorated entrance into the city that also has the benefit of leaving behind archaeological evidence that it truly existed (via World History Encyclopedia).

The 1st century Roman historian Diodorus Siculus seemed especially fond of the obelisk erected by the semi-mythical Assryian queen Semiramis. In his biography of her life, Diodorus reports that Semiramis had a massive stone quarried from Armenia and, after an epic journey involving many beasts of labor and a trip downriver, set the rock up as an obelisk in her kingdom. "[T[hey number it among the seven wonders of the world," he wrote.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the only wonder still standing

Talking about the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World often means talking about ruined buildings, destructive earthquakes, and the kind of social upheaval that leaves a previously grand structure in ruins. But, while it's true that the majority of the list no longer stands, there's at least one ancient wonder that has truly stood up to the test of the: the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Located in Giza, Egypt near the modern capital of Cairo, the Great Pyramid is actually the biggest in a complex of pyramid tombs, according to the World History Encyclopedia. It was one of the tallest known structures in the world for thousands of years, rising nearly 500 feet high. And, with some staggeringly huge stone slabs incorporated into the pyramid, the sheer engineering acumen needed to construct the pyramid and not see it immediately crumble into a pile of rubble is awe-inspiring even by modern standards.

That said, the Great Pyramid that you can visit today isn't the exact same as what the ancient Egyptians would have seen when it was completed around 5,500 years ago. Originally, the pyramid would have been covered with bright white limestone, which would have made the result all the more visible for miles around. But the stone was later removed for use as building material in nearby Cairo. What you see today, though still incredibly impressive, is really just the core of the original Great Pyramid.

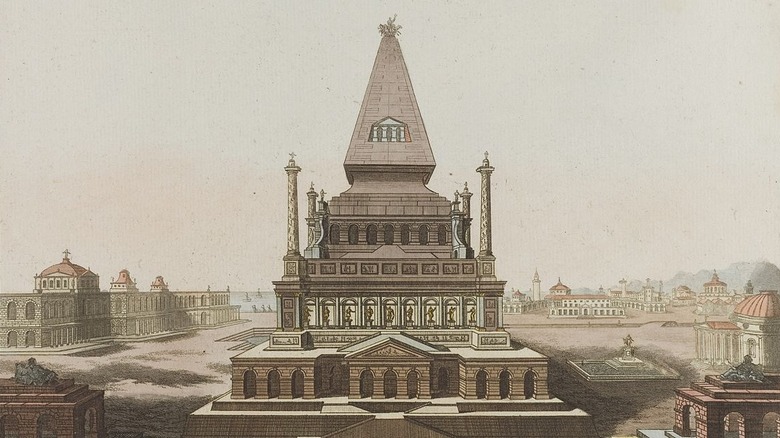

Another wonder was a massive tomb

Upon first consideration, a mausoleum may not seem like the most exciting thing to visit. If you like to wander through your local historical cemetery, you may have seen these free-standing little buildings that inter human remains above ground. Some sport beautiful stonework and historic importance, sure, but you probably wouldn't make one the focus of a field trip.

But those relatively small structures, while clearly expensive and often striking in their own right, don't really hold a candle to the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.

The mausoleum in question was a huge marble tomb built in what's now Turkey. As ThoughtCo reports, it was built to house the remains and promote the reputation of Mausolus of Caria, who died in 353 B.C. near what's now Bodrum, Turkey. His widow, Artemisia, was actually the one who ordered the construction of her husband's final resting place. She reportedly channeled her grief into creating the tomb, which required the services of multiple sculptors and enough marble to create a 140-foot high structure.

Unlike some of the shorter-lived entries on the seven wonders list, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus stood for an estimated 1,800 years. A series of earthquakes in the Middle Ages demolished the mausoleum, and the remaining stones were used to complete other buildings, per the World History Encyclopedia.

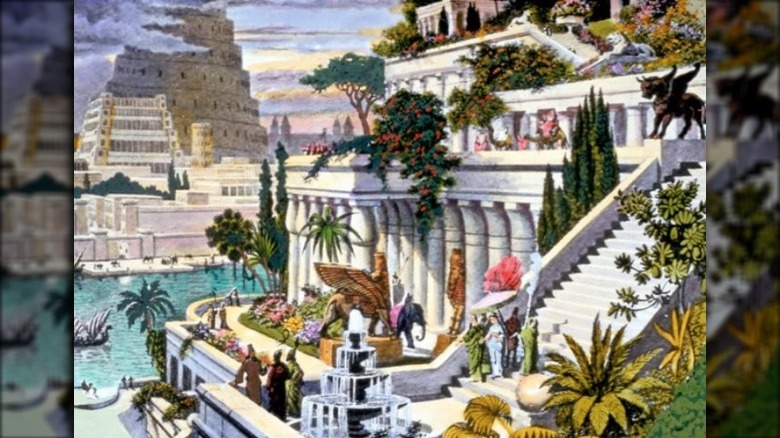

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are hard to prove

Perhaps one of the most controversial entrants in the list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. According to the World History Encyclopedia, the story goes that they were constructed under the orders of King Nebuchadnezzar II sometime in the 6th century B.C. They were supposed to be a series of pleasure gardens, built with an intricate irrigation system on top of stone terraces, all in a notoriously arid landscape. But there's been no physical evidence uncovered for the gardens, making historians highly suspicious.

That's not to say that there isn't some evidence for the gardens, though it's all based on written accounts before a time when many people bothered with things like fact checking or peer reviews. Irving Finkel, writing in "The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World," says that five writers left accounts that might lead you to believe that there's something to the story after all. Then again, skeptics can easily counter that with the distinct lack of Babylonian records. And wouldn't they have wanted to record or even boast about such a grand wonder in their own cuneiform tablets?

It could be that people just aren't looking in the right place. According to History, some believe that the gardens were actually in Nineveh, an Assyrian city that, among other things, boasted an extensive irrigation network.

There was technically more than one Temple of Artemis

Per the World History Encyclopedia, the Temple of Artemis was built in the Greek outpost of Ephesus (now modern-day Turkey) in the 6th century B.C. Quite a few folks in Ephesus were devoted to the chaste hunting goddess Artemis, also bringing in elements of other fertility goddesses like the Egyptian Isis or Asia Minor's Cybele.

The temple was built by a conquering king, Croesus, who went on a building campaign after taking over the city around 550 B.C. He was actually riffing on previous temples but, perhaps in a bid to make himself look good, pulled out all the stops on his building. Only, given that it took well over a century to finish the massive, elaborately decorated temple, Croesus wouldn't have lived to see it in its final form. Still, it was reportedly very impressive, packed full of artworks and over a hundred 60-foot high columns that took some serious engineering know-how to move into place.

Then, after about two centuries of everyone admiring the temple, things went south. According to ThoughtCo, the first serious blow came in 356 B.C., when an arsonist burned down the temple. The people of Ephesus rebuilt the temple but, some five centuries later, invaders ruined it yet again. The World History Encyclopedia contends that the true end of the Temple of Artemis came at the hands of a 5th century Christian mob looking to destroy all traces of paganism in their city.

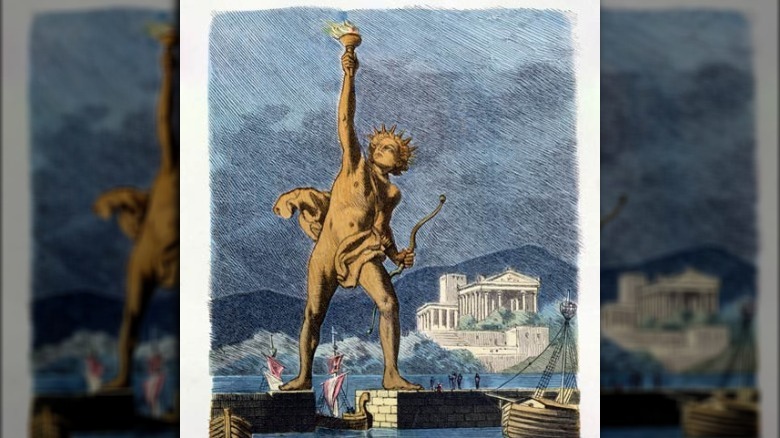

No one can agree on the look of the Colossus of Rhodes

This giant statue, which some say straddled the harbor entrance to Rhodes in Greece, was widely acknowledged as a marvel throughout the ancient world until a massive earthquake toppled it. But, before that event, it reportedly wowed ancient travelers with its massive height, reaching around 33 meters, or over 100 feet, into the skies, per the World History Encyclopedia.

Made out of sheets of bronze by a renowned Grecian sculptor, it surely would have gleamed and shone for miles around under the bright Mediterranean sun. The statue itself was meant to depict Helios, the sun god who was worshipped throughout the region and eventually became practically synonymous with Apollo.

While there are multiple textual accounts that claim to confirm that statue's existence, there are some inconsistencies in these accounts that make some modern people skeptical. National Geographic reports that those accounts are generally pretty vague on the particulars of the Colossus, like what it looked like, how it was constructed, or how it may have stood over or simply next to one of the city's harbors. We can't easily investigate those sorts of details now, however, as the statue, if it truly existed, is long gone.

Ancient writers generally agree that the massive, shining statue of Helios crashed to the ground in an earthquake that took place around 225 B.C. This meant that it stood for less than 60 years, making it the shortest-lived wonder on the list.

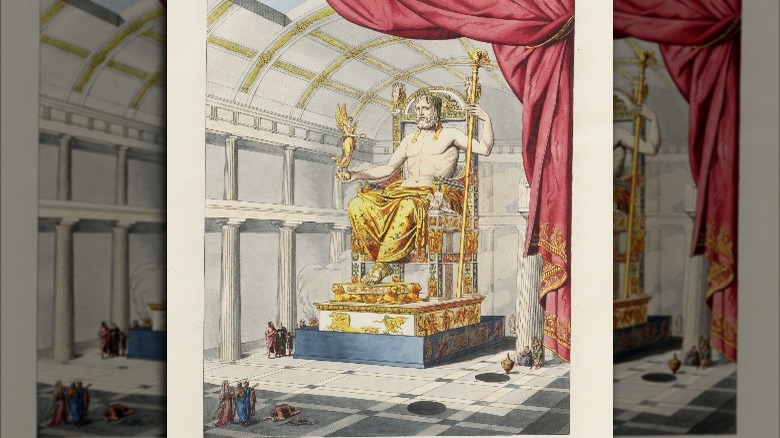

The Statue of Zeus stood very tall

When you're making a monument to the chief of the gods, someone is eventually going to want to lay it on a little thick. But when it comes to the famously tempestuous Zeus, it probably doesn't hurt to make that statue extra flattering.

The rather flattering Statue of Zeus stood in Olympia, Greece, and was created in the 5th century B.C., per the World History Encyclopedia. The temple in Olympia was already a pretty big deal, so it perhaps isn't all that surprising that the ancient sculptor Phidias wanted to go big when creating the sculpture. He and his artisans produced a 40-foot statue made of gold and ivory that showed the head of the Greek gods sitting on a magnificent throne and garlanded with olive branches. The gold sheets and ivory were applied over a wooden center, and accented with smaller amounts of materials like jewels, dark ebony wood, silver, glass, and more.

It was such a stupefyingly large statue that some ancient writers actually complained, saying that the Zeus figure was too big for the temple (via "The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World"). Still, given how many people flocked to wonder at it, those quibblers seem to have been in the minority. All told, this statue survived for about 800 years, says ThoughtCo, until the Christian Emperor Theodosius II ordered the bulk of it dismantled and burned in the 5th century A.D. Any remaining bits were destroyed in a subsequent earthquake.

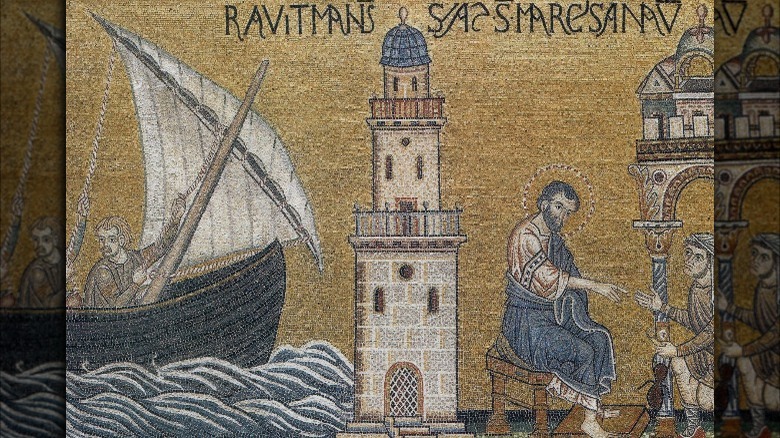

The Lighthouse of Alexandria added to Egypt's prestige

It may seem a odd that a functional building like a lighthouse should make the list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but the Lighthouse of Alexandria was, both for its time and ours, a pretty big deal. According to the World History Encyclopedia, it not only provided a navigation light for ships arriving in Alexandria, Egypt's bustling harbor, but was also an architectural wonder. Previous lighthouses were utilitarian, but this one was apparently pretty impressive in its own right, though ancient writers are frustratingly vague on the details.

We can be reasonably certain that the lighthouse, built sometime around 300 B.C., had three floors and featured a statue of Zeus on the top level. It was also apparently pretty tall for the ancient world, ranging somewhere from 330 to 460 feet in height. Later Arab writers also mentioned a ramp that curled around the outside of the tower, as well as a mirror that would have amplified the sight of the lighthouse's flame across the waters beyond.

Even Julius Caesar was duly impressed, writing that the lighthouse was "of great height, a work of wonderful construction, which took its name from the island," the Pharos on which it sat. Yet, like so many other entries on the list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it's no longer standing. It was damaged by earthquakes on a number of occasions, finally vanishing from the record sometimes in the 14th century A.D.

Some have proposed a new list of wonders

It's clear that there are some limitations to the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Ancient European writers, while sometimes fairly well traveled, still couldn't have known much about wonders outside of the ancient Mediterranean. Their world was necessarily limited by hard factors like the ability to travel only certain distances in what, to us, now seems like fairly primitive seafaring craft. No one was jetting off to Central America from Greece, that's for sure.

But, now we have the ability to learn far more about the ancient world, regardless of our own geographic restrictions. So, more modern researchers and writers have put forth a series of more inclusive lists that hit a few more continents in the quest for wondrous human-made sights. Britannica reports that these include things like the thousands of miles long Great Wall of China, the 9th and 10th century city of Chichén Itzá in Mexico, and the grand 17th century mausoleum in Agra, India known as the Taj Mahal.