The Untold Truth Of The Book Of Genesis

On the surface of it, the biblical book of Genesis can seem pretty intimidating. It starts with the creation of everything from seemingly nothing, after all. The book then follows up with a quick succession of dramatic tales, from the origins of sin and death to a flood narrative that implies all terrestrial creatures built themselves back up from a small group on a very large wooden boat. All told, if you were to just concentrate on what's contained in the text without any reference to things like historical context, you'd still be occupied for a lifetime.

But, take a step back, and you'll see that there's a lot more to be learned about this opening book of both the Hebrew Pentateuch (the first five books of the Torah) and the Christian scriptures. How did Genesis come to be? Someone had to write it down, after all. And how has it changed over the course of history and with different translations? Why does it sometimes contradict itself, and also repeat certain themes over and over? Let's dive into the untold truth of the Book of Genesis.

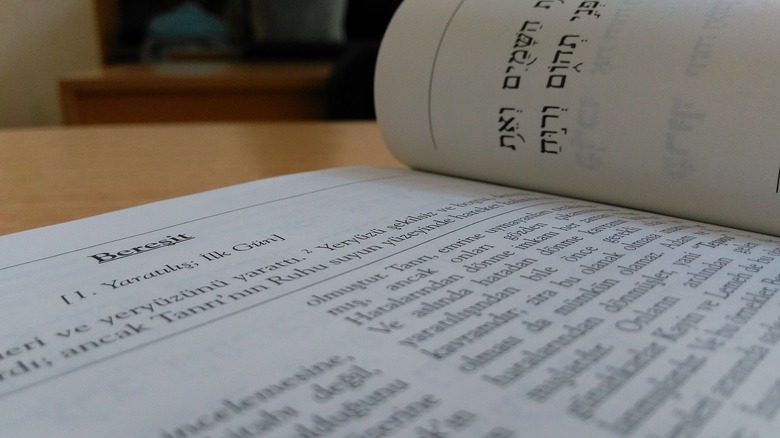

The book's title derives from Hebrew

The Book of Genesis may sound like it's set in stone, but the truth of the matter is that even the very title of this first book of the Pentateuch and Christian Bible is quite a lot less confirmed than you may think. According to Columbia University, the initial Hebrew title is actually "bereshit," which roughly translates to "beginning" — thus the opening lines in many translations that kick off with "In the beginning." The later title of Genesis is actually the product of subsequent Greek translators, who employed the word for "origin" or "birth" in the place of the first Hebrew word.

Per "Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation," this single-word title is also arguably a reference to "generations." That certainly makes sense for this notoriously lineage-focused book. Anyone who's read through Genesis in any of its translations already knows that the book spends quite a bit of time listing various notable people who begat sons, who themselves begat sons, and then yet more sons, and on and on for many lines.

Some scholars argue that Genesis is just as much of an accounting of the history of the Jewish people as it is a tale of the beginning of the entire universe. Who's in your family tree ends up being a pretty big deal, as both Genesis and the rest of the Bible make clear.

Genesis was developed over centuries

It may be easy to think that Genesis just appeared in its whole form one day, written by a single creator. But if you were to ask a scholar of biblical history for the lowdown on just how the Book of Genesis was assembled, you'd get a very different story.

That's because researchers generally agree that Genesis is a collection of multiple narratives that were individually constructed and eventually assembled into one text over a very long time. According to "The Oxford Companion to the Bible," it took hundreds of years to accomplish. With that in mind, it's pretty futile to wonder about the author of Genesis, as many unnamed and unknown people could lay claim to at least a portion of the credit. It's more useful to think about the sorts of groups that would have produced these stories and why topics like creation, lineage, and a monotheistic God were so important to them and their sense of identity.

The occasionally interconnected and sometimes fragmentary bits of origin story also likely come from oral histories that had been around for generations before they were finally written down. In fact, as theorists referenced by the journal Oral Tradition argue, Genesis doesn't really make sense unless you accept that much of it started as accounts told by word of mouth, rather than written down right away.

The Book of Genesis may have Mesopotamian roots

Like many of the early parts of the Bible, a careful reading of Genesis often leads back to the Mesopotamians. It makes sense, given the historical context of how some of these Hebrew texts came to be. In the 6th century B.C., a series of battles and conquests meant that quite a few Jewish people were exiled to Babylonia, a period often referred to as the Babylonian Captivity (via Britannica). There might have been some cross-cultural communication during this period that influenced later Hebrew scriptures.

In fact, certain narrative threads in Genesis appear to link back to Mesopotamian legend, including an Akkadian creation myth known as the Enuma Elish. Bible Odyssey notes that both narratives include an all-powerful male deity shaping chaos into order and creating humans for a special purpose on the sixth day of creation. There's also Ziusudra, a Mesopotamian man who was alerted to an incoming divinely sent flood, per Britannica. Ziusudra, widely acknowledged as a good and dutiful man, built a massive boat, survived the deluge, and thanked the gods for his survival — very much like Genesis' Noah.

According to Michael Zank, a professor of religion at Boston University, early Hebrew writers could have encountered the story of Enuma Elish and created their own version.

The six days of creation have created a theological puzzle

Genesis pretty plainly states that God created everything in six days, and then rested on the seventh. However, as the BBC reports, the exact timeline is a bit confused. The first chapter of Genesis says that humans were created on the sixth day, while the very next one implies that humanity was actually made before animals. Genesis 2 claims that "God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life," and only then went about the business of creating plants and animals.

But theologians have argued more about the book's concept of days. Some people think it's meant to be taken literally, but that's hardly a consensus amongst even the Christian faithful. BioLogos reports that this has been a subject of debate for centuries and has since produced a few different interpretations. There's the literalist view, where "day" means, well, an actual day as we understand it. Others say that it's more appropriate to interpret "day" as an extended "age" that could potentially cover thousands or even millions of years.

The literary view of the language of God's creation focuses more on the themes and people of Genesis without getting wrapped up in arguments over what, exactly, counts as a day.

Genesis appears to have multiple authors

So, who wrote Genesis? A close reading of the text indicates that more than one group of people had their hands in creating Genesis. How do we know this? In part, because the narrative repeats and sometimes contradicts itself. "The Book of Exodus: A Biography" explains that the very first two chapters of Genesis can't seem to agree with one another. Seemingly important details, like how long it took God to create everything and in what order, simply don't line up. And, later on, a close reading will reveal that there are actually two different flood stories that are rather clumsily woven together.

According to Columbia University, the general consensus is that the first five books of the Bible, also known as the Pentateuch, come from multiple authors and multiple sources. Four are identified as "J", "E", "D", and "P." The letters refer to various hallmarks of an individual source. "P," for instance, is short for "priestly source," which seems to be especially focused on the Jewish priests and their role in the story. And, if that weren't confusing enough, there appears to be a fifth source, "R," that's responsible for taking the four pre-existing narratives and attempting to assemble them into a single book.

Genesis repeats itself for a reason

Genesis, like some other biblical books, tends to repeat the same or very similar stories. That may seem like a mistake at first, and it's hard for modern readers to do anything but conclude that the "R" source just wasn't paying close attention when it fused everything into the Book of Genesis. That's quite possibly the case in multiple instances (and may also be the smoking gun when it comes to proving that the New Testament Gospels are copying each other, according to The Great Courses). But there's a bit more going on beneath the surface.

All that repetition is a rhetorical device meant to emphasize certain key themes and incidents in Genesis and the rest of the Hebrew Bible, as the Washington Post argues. It's arguably a literary device to use similar language to link Eve's fateful consumption of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge and the manner in which the "Sons of God" took up with human women prior to the Great Flood. Neither turns out well.

Repetition may also link back to the oral traditions that likely preceded the Book of Genesis in the first place. It's certainly a tactic for storytellers and listeners alike to recall important details and story beats, as the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute notes. In fact, it's such a vital technique that it's a hallmark of oral storytelling worldwide and throughout history.

One theory about the origins of the book is controversial

Most scholars of religion and faithful Christians agree on the basic facts of Genesis, like the evidence that it came from multiple sources and likely has its roots in oral storytelling traditions. But that doesn't mean the study of the Book of Genesis isn't without controversy. When it comes to talking about the inspiration behind its words and why it was finally written down, things can get kind of heated.

One especially thorny proposal is often known as the Persian imperial authorization. As "The New Cambridge History of the Bible" explains, the theory is that Persian/Babylonian rule of the Hebrew kingdom of Judash in the 6th to 4th centuries B.C. was key to producing local legal codes, like those outlined in Genesis and other Hebrew scriptures like Leviticus. One writer, Peter Frei, went so far as to say that these early law codes could be linked to later, more codified legal systems.

However, few want to go so far as to say that Persian overlords explicitly commanded the production of a semi-unified narrative in Genesis or a Jewish legal code. Yet, as Konrad Schmid at the University of Zurich argues, neither is it entirely fair to dismiss the idea that Persian authorities didn't have some influence here, whether or not they specifically told someone to codify the Book of Genesis or created an environment that led to the same result.

Promises, blessings, and duty are major themes

The matter of covenants between the Hebrew people and God — and how both sides fulfill those agreements — is a major theme in Genesis. Indeed, it's such a prevailing focus that it all comes back to those covenants in one way or another, oftentimes in repeated themes like lineage lists and acknowledging blessings, says "Genesis."

Those benefits, however significant they are, do come with a steady change in interactions. In earlier chapters of Genesis, God appears to walk in the Garden of Eden and directly interact with Adam and Eve (via Got Questions). Yet, generations later, he seems more interested in communicating via dreams and visions, having become somewhat more distanced from the everyday life of humanity.

According to "Genesis," blessings from God are a pretty big deal in marking out not just important themes, but who is set to become a major figure in the Bible, like Abraham. But those boons are also contingent on humans paying it back by fulfilling their duty and obeying divine commands, even when it hinges on seemingly odd and work-intensive tasks like building a giant boat in the middle of an arid region (via "Genesis"). Then there's also the terrifying test faced by Abraham in Genesis 22. Abraham was asked to sacrifice his son, Isaac, but then deterred at the last minute by a heavenly angel for following his duty to nearly the last, deadly instant.

Three wife narratives in Genesis are strikingly similar

Genesis contains three very similar stories, in which biblical patriarchs travel to foreign lands and pretend that their wife is their sister to avoid violence. Per My Jewish Learning, the first and second instances are both courtesy of Abraham, who pretends that his wife, Sarah, is actually his sister while the pair are traveling in Egypt and elsewhere. His reasoning? Sarah is apparently very, very attractive, to the point where heart-eyed locals might consider doing away with Abraham to get access to his wife.

Isaac, another Biblical patriarch, does pretty much the exact same thing with his own wife, Rebekah, in a later chapter. All in all, it's not an especially good look, with two major figures in Genesis capitulating to their own fears and denying key relationships, all to save their own skins.

What's going on here? There's repetition all over Genesis, sure, but this is arguably more extensive than emphasizing words or themes over and over again. These may be variations on a single story or quasi-manufactured narratives created to make a point about power and will, according to the journal Judaism. It could also be that they were meant as a reflection of complex social and political states in the ancient world. My Jewish Learning notes that it might also reflect "wife-sistership," where a wife could be adopted as her husband's "sister" and given the increased rank of being a blood member of her husband's family.

The role of women in Genesis gets complicated

A quick perusal of Genesis shows that it's pretty patriarchal. The book features long lineage lists that exclusively focus on fathers begetting sons, but it has little to say about daughters. However, women do feature in this book. A closer examination of their roles hints at a more complicated picture of gender in the Bible that goes beyond a female model of submissiveness and dependency.

First, as "Mothers of Promise: Women in the Book of Genesis" points out, the women of Genesis do have a fair amount of ink devoted to their stories, especially in relation to their roles as mothers and wives. And, as Genesis makes very clear on multiple occasions, the matter of one's progenitors — male and female — is key to determining whether or not you're one of God's chosen people.

Yet there's another side to this story. While there are plenty of women who are held up as honorable matriarchs, Women in Judaism argues that, in Genesis and other Hebrew texts, they are complicated and complicating figures who may get in the way of God's will via insubordination. That's not to say that they are "bad" or that modern readers need to interpret them in this way. In fact, the Denison Journal of Religion notes that their stories contain valuable lesson about how to be an honorable human, from treating one's spouse right to sustaining one's faith while still living as a complex human being.

Storytelling in Genesis may be more important than truth

All of this debate over both the larger and finer points of Genesis may seem like a lot of quibbling, and for the faithful, it may be ultimately more important to focus on the spiritual messages contained within the book rather than sdetails like priestly sources and potential links to Babylonian creation myths. And, for the people who began telling the stories that eventually became the written Hebrew texts, the nature of truth may not have been all that important in the first place.

Though modern readers may focus on the need to separate myth and truth, that wasn't necessarily the point for the original authors of Genesis. The Journal of Biblical Literature notes that terms like "history" and "fiction" are already pretty tricky to nail down. For the text's writers, storytelling may have been used in an attempt to order a narrative in a coherent and spiritually meaningful form. It almost certainly wouldn't have been part of a conscious and malicious attempt to deceive people. And, as "The Oxford Bible Commentary" notes, it's perhaps most useful to see Genesis and the rest of the Pentateuch as part of a movement on a grander scale, meant to bolster the shared sense of Hebrew identity and nationhood under an all-powerful and protective God.