The Untold Truth Of The Hanging Gardens Of Babylon

Whenever people put aside petty squabbles, "he-said, she-said" arguments, and stop acting like siblings that have been stuck in the back seat of a station wagon for 12 hours, they're capable of doing some pretty amazing things. The American Society of Civil Engineers has released their list of modern wonders of the world (via Wonderful Engineering), and they're things like the Golden Gate Bridge and the Empire State Building. Even more impressive are the massive structures built before things like mass production and power tools.

Most people have heard of the Seven Wonders of the World, and in spite of their centuries of fame, there's still a ton we don't know about them. There's one — the Hanging Gardens of Babylon — that has so much mystery surrounding it that no one can even agree on whether or not it actually existed.

It seems almost inconceivable that no one knows: It's kind of like people 2,000 years in the future debating the existence of the Eiffel Tower. So, let's take a look at the stories, the evidence, and try to answer the question of whether or not it was even possible to terraform part of the desert into a lush, hanging garden... centuries before the start of the Roman Empire.

What's the story here?

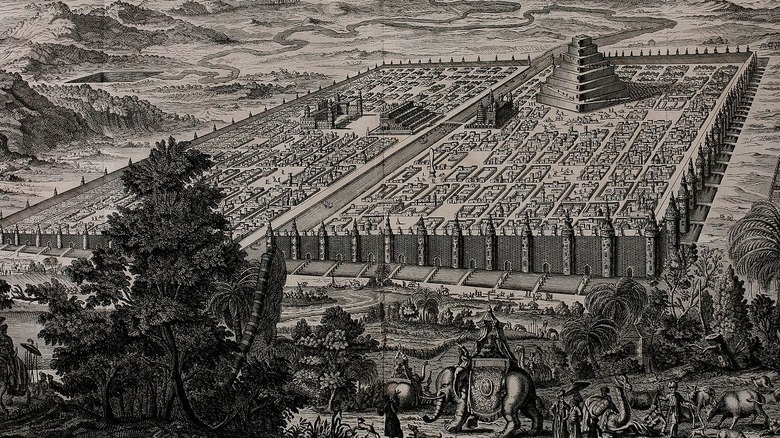

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are, of course, often said to have been one of the marvels of the ancient city of Babylon, which was founded around 2300 BC. It had a pretty long history of being destroyed and rebuilt numerous times over the centuries, and it's said that the Hanging Gardens were an addition to the city that happened sometime in the 6th century BC. (That's about 500 years before the founding of the Roman Empire.)

Ruling at the time was the warrior-king Nebuchadnezzar II. After conquering the Assyrians and seizing control of Nineveh (which will become important to the history of the Gardens), he moved on, sacked Jerusalem, and enslaved the elite in a part of Jewish history called the Babylonian Captivity (via World History).

When he returned home, he kicked off a massive building campaign that turned Babylon into the biggest and most beautiful city in the world. He'd also gotten married to a Persian princess named Amytis, and the story says (via ThoughtCo.) that when she moved to Babylon, she missed the verdant green of her homeland. Not one to let his beloved bride suffer, Nebuchadnezzar II built her a massive desert oasis, a man-made, tiered, mountain-like retreat that was covered in all the plants and trees she missed. It was so impressive that it became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

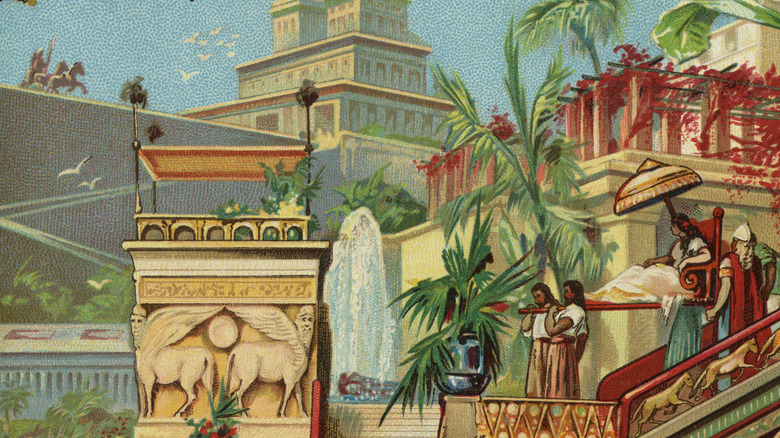

No one knows what the Hanging Gardens of Babylon looked like

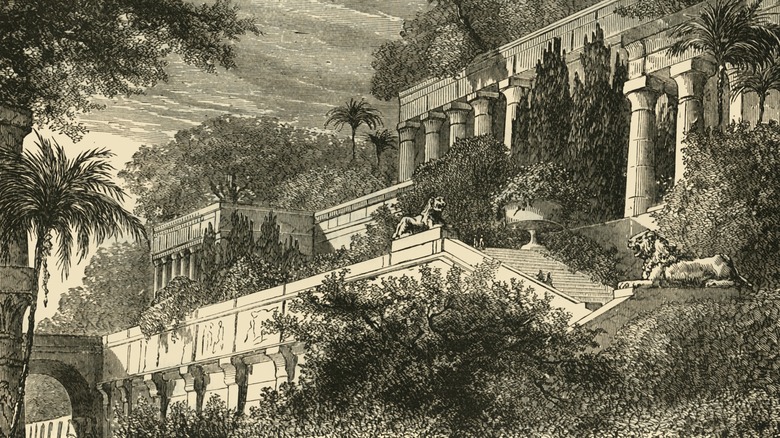

There's a ton of paintings and illustrations of what artists think the Hanging Gardens looked like, but there's the thing: No one is 100% sure just what a "hanging garden" is. National Geographic says archaeologists and historians have been debating interpretations for a long time.

That makes them a little different from the other ancient wonders, which were pretty straightforward. There's actually a good reason for that: Babylon, says History, sat on the banks of the Euphrates River south of what's now Iraq's Baghdad. It wasn't easy for the writers of the Hellenistic world to visit, so World History says most of the descriptions that have been preserved were written centuries after Nebuchadnezzar II, by people who had never actually been to Babylon. That means they're not the best, more reliable witnesses, but let's look at what they do say.

One of the first people to write about them was the Roman Josephus, who was penning his tale in the first century AD. He wrote (via The Gardens Trust) about "very high walls, supported by stone pillars ... [and] planting what was called a pensile paradise." Giggles aside, "pensile" was defined as "suspended from above, ... OR set or poised on a declivity — i.e. overhanging." That vague description has been turned into artists' depictions of a tiered, sprawling, and overhanging garden, but it's possible that's completely wrong.

The presence — and lack of — textual references

Here's where the detective work really starts. Livius says that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were mentioned by a score of ancient writers, including Strabo, Flavius Josephus, and Cleitarchus. Maybe the most important of those was a Greek engineer named Philo, who National Geographic credits with being the one who first assembled the list of the Seven Wonders.

He called them the "temata," or "things to be seen." Many — like the Temple of Artemis — he would have had a good chance to see in person, but Babylon's Hanging Gardens? Not so much. By the time he was writing in 225 BC, Babylon had already fallen about a century prior. That's kind of like someone in 2020 recommending people should really visit the marvel that was the world's first Ferris Wheel, built in Chicago for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

Philo lauded the gardens for their wide range of flowers, plants, and trees, all — he said — planted along the top of trellises sitting on stone pillars, which sounds incredibly impressive. That's not surprising, especially considering he was drawing on a source written by Alexander the Great's court historian, a scholar named Callisthenes. He was writing in the 4th century BC, but his original works are long gone.

Here's why some think the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were fictional

Some historians and archaeologists believe the Hanging Gardens were completely fictional, and they have some compelling evidence — starting with the story of why they were built in the first place.

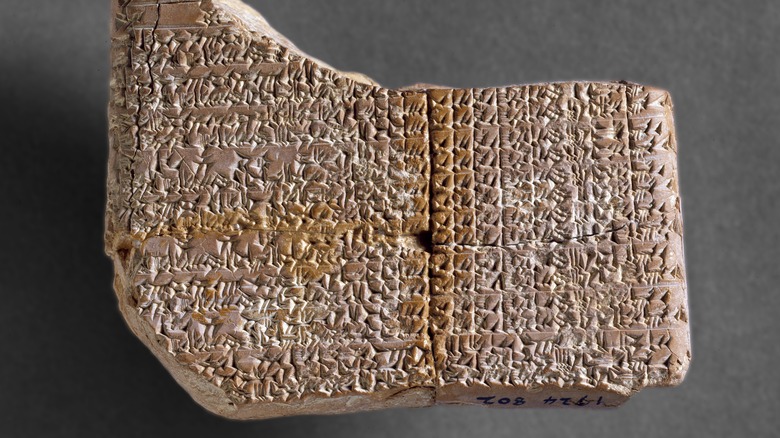

Louise Pyke, an Honorary Research Associate and Lecturer from the University of Sydney, notes (via The Conversation) that Nebuchadnezzar wasn't just real, but that contemporary records from his reign — in the form of cuneiform tablets, like the one pictured — support some of the events in the Bible's Book of Daniel (as well as in other books). There's a lot of documentation there, but what's not there is any mention of Nebuchadnezzar's beloved wife, Amytis. World History says that she's so conspicuously missing from historical records that it's impossible to prove she even really existed. And that's super weird, because Nebuchadnezzar was a dedicated record-keeper. Rebuilding the city of Babylon into something spectacular was what he was all about, and he kept extensive records on all of his building projects. The Hanging Gardens, though, are never mentioned as being a part of those massive renovations.

One of the early documentations of the Gardens comes from Alexander the Great's court historian, who National Geographic says would have been writing well after the building and completion of the Gardens. In all of the thousands of tablets preserved from Nebuchadnezzar, there are exactly zero mentions of such a wonder. Anywhere.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon had another name, too

Sure, the Hanging Gardens aren't mentioned anywhere, but as World History notes, Herodotus left the Great Sphinx out of his description of the Giza complex entirely, and we definitely know the Sphinx is, in fact, a thing that's there. Since historians have an example of ancient writers not acknowledging monuments that are definitely there, that can add another check in the "maybe" category.

It's also worth considering that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were sometimes referred to by a different name: the Hanging Gardens of Semiramis. That clears up absolutely nothing, because Semiramis comes with her own set of questions. She was an Assyrian ruler from the 9th century BC — a few centuries before Nebuchadnezzar. Her original name, says National Geographic, was Sammu-ramat before it was Hellenized to Semiramis, and no one can really decide what she was.

Sammu-ramat ruled for just five years, and records have her as a fearless military leader, the builder of Babylon, a tragic figure at the center of an ancient love story, and some credit her with a semi-divine heritage. It was the Greek writer Strabo who credited her as being the creator of the garden, but according to Oxford Reference, Strabo lived between 63 BC and 23 AD. That was nine centuries after Sammu-ramat, and it's unclear just where this idea came from — there's no historical records of such a connection.

The ancient Babylonians had the capabilities to build the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Sciencing says that ancient Mesopotamia had much the same climate as modern-day Iraq. More specifically, that's occasional rainfall, summertime temperatures up to 110 Fahrenheit, and mild winters. That means gardens on the scale of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon would need a ton of water in order to thrive. Diodorus Siculus wrote (via World History) that the terraced garden was 65 feet high — was it possible for them to get that much water to the top of an almost 7-story building?

In short: Absolutely. Ancient Babylonians were wildly intelligent: LiveScience says that modern-day astronomers still use their data to track the way in which celestial bodies have changed over the course of centuries. Where the city was located meant that rain wasn't enough for even the kind of agriculture necessary to feed the people, so they came up with and built a massive irrigation system.

That's not an exaggeration, either. A single canal named "Hammurabi-is-the-abundance-of-the-people" was around 100 miles long (via ResearchGate), while Penn Museum says that clay tablets left behind by ancient engineers show maps of extensive canals built not just for irrigation, but transportation. They also had reservoirs, levees, and aqueducts, says the Water Encyclopedia, with laws in place that said it was everyone's civic duty to help keep the system running.

There's one technology in particular that's called out as being crucial

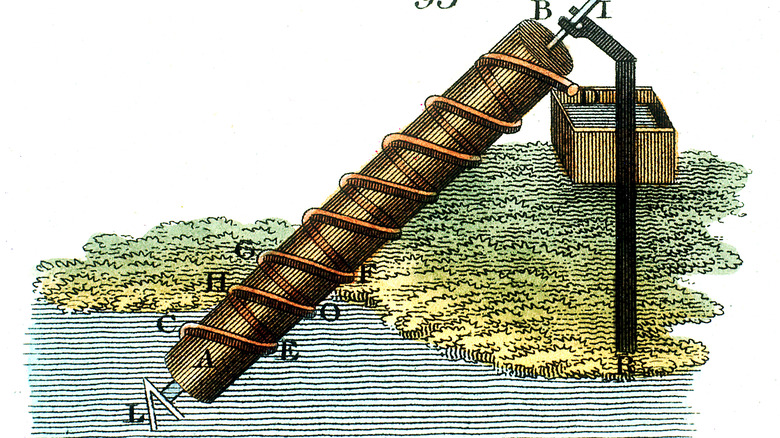

When Oxford University's Stephanie Dalley re-translated some ancient cuneiform tablets, she found descriptions of a massive irrigation system and a tower of gardens. The Guardian says her 18 years of study have produced some fascinating discoveries, and among them is a description of one device that was instrumental in raising water to the top levels of the gardens.

The thing that makes watering plants at the top of a 7-story building possible — without, at least, the labor of a small army of people — is what they called "a water-raising screw made using a new method of casting bronze."

It was a massive discovery for a few reasons. Not only did it make the possibility of the gardens much more realistic, but the idea is what's now called the Archimedes screw. It's essentially a spiral tube that, when one end is submerged in water and then the tube is turned, the water moves upwards. History Answers says it's called the Archimedes screw because it was long thought to have been invented by the Greek inventor sometime in the 3rd century BC, but with the reference discovered in the tablets, it suddenly seemed as though the idea had been around much longer — at least, in Babylon.

The turn-of-the-century German excavation

It took a surprisingly long time for the first real excavations to be carried out in the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon, and according to National Geographic, the first was run by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey. He spent 18 years there starting in 1899, and he fully believed that he had discovered the ruins of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

There was some compelling evidence that the building in question was, in fact, the gardens. Instead of being made from the more common mud brick, this was solid stone. Koldewey argued that was necessary because of how much water the structure would be exposed to, and he also said that it would have been able to more easily — and safely — support the weight of the terraces, dirt, plants, and water. He also uncovered wells on the site, and it all sounds pretty great, right? Not so fast. Further excavations have uncovered tablets at the site, which weren't inscribed with care instructions for plants, but with lists of things like spices, oils, grains, and instructions on what resources were going where. Add in a few storage jars, and it's more likely the site was actually a warehouse.

Koldewey didn't come up empty-handed, though: SciHi says that he discovered the very real Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, along with the foundations of a building that was the inspiration for the Biblical Tower of Babel.

Ancient gardens were a huge deal

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are a world wonder for a reason — it's hard to imagine something on that scale. But epic gardens were actually a major part of ancient cities, so much so that The New York Times says that Mesopotamian kings were often given the title of "Gardener" to refer to the inevitable cultivation of their people under their watchful eye.

Throughout the ancient world, gardens were cultivated on the huge scales of the rich and powerful, on the smaller scale of Greek and Roman houses, to the wildness of sacred groves and gardens with trees and plants associated with some of the most popular gods and goddesses.

And they were pretty amazing ground-level and roof-top gardens that covered homes in fragrant greenery, and they almost always included statues, columns, pillars, and even water features — some of which sported bronze birds that sang with the help of hidden machines. In areas that weren't suitable for actual gardens, frescos were often painted to bring the feel of a garden to an area — or, says World History, they were sometimes painted along garden walls to make the space seem even bigger. In one respect, it doesn't matter at all if the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were real or not: The stories of this magnificent building are thought to have created the inspiration for all the millennia of gardening that's come since.

They may have actually been the Hanging Gardens of Nineveh

It turns out that a few very different viewpoints on the existence of the Hanging Gardens might be correct, and at the same time they were never built in Babylon, they still may have been very real. That's because calling them the "Hanging Gardens of Babylon" might be a complete misnomer, and they should actually be called the "Hanging Gardens of Nineveh." As bizarre as it sounds, that's the conclusion of Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford University scholar who specializes in ancient Middle Eastern languages. She's spent more than 18 years studying and translating scripts from not just ancient Babylon, but Assyria, too.

According to The Guardian, Dalley says that while there aren't any references to the Hanging Gardens in Babylonian texts, correct translations of cuneiform scripts from the reign of the Assyrian king Sennacherib contain detailed accounts of an elaborate irrigation system that stretched for more than 50 miles, and ended in an "unrivalled palace [built as] a wonder for all peoples." Sennacherib described his "Incomparable Palace," saying it was meant to feel like the Amanus mountains.

Because of the conflict in the area and inherent danger, Nineveh (now Mosul) hasn't been as thoroughly excavated as possible. Still, evidence is tantalizing: Not only have parts of the aqueducts and irrigations systems been documented, but The Gardens Trust points out that carved reliefs discovered in Nineveh depict tiered gardens that look pretty much exactly like the Hanging Gardens were described.

Wait, so they got entire cities confused?

If the ancient city of Nineveh was the actual home of the Hanging Gardens and they were built by the Assyrians — who were long-time enemies of the Babylonians — why the heck have they always been known as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon?

According to National Geographic, there's actually a fairly rational explanation for misplacing a structure so impressive it was deemed one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Most of the scholars who were writing ancient history were Greek and Roman, and there's plenty of instances where they get the kingdoms of Babylon and Assyria confused. (Anyone who scoffs needs to sit down and try to place all 50 states or all the provinces of Canada on a map.) Not only were these far-away, exotic places that weren't easily accessible in the ancient world, but Oxford scholar Stephanie Dalley says (via The Gardens Trust) that there was something else causing confusion.

It all comes down to translations. Babylon, she says, literally means "Gate of the Gods." Meanwhile, in Nineveh, the city's massive gates were, in fact, named after individual gods. That means while there was a city named Babylon, there was also a city that was "a" babylon — and that all got even more confusing in 689 BC. That's when Assyria conquered the city of Babylon, and Nineveh started to be called "New Babylon."

What happened to Babylon and Nineveh?

So, what happened to Babylon and Nineveh? (In other words, how did the world manage to misplace one of the Seven Wonders?)

Babylonia and the Assyrians had been fighting for a good long time when others joined the fight. In 625 BC, the Scythians, the Medes, and the Persians also joined the fray, and Nineveh was burned to the ground in 612 BC (via World History) — along with any traces of the Gardens. The Assyrian Empire was split up among the victors, and today, Nineveh is now known as Mosul, a city that National Geographic says has suffered mass destruction of ancient buildings under the heel of ISIS.

In the grand scheme of things, ancient Babylon didn't last much longer. The Persians moved in to take Babylon in 539 BC, but it remained a massively influential city and hub of civilization for several more centuries. The beginning of the end came with Alexander the Great — according to History Extra, Alexander decreed that Babylon was to be preserved under his rule, but when he died and others moved in to pick apart the pieces of his empire, Babylon — and much of its history — was a casualty of the fighting. Today, the city is little more than a modern reimagining of an ancient juggernaut.