Was Bloody Mary Really England's Most Evil Queen?

To attract the epithet "Bloody" amid the barbarity of Tudor England takes some doing, but it's a name that has stuck for centuries to Queen Mary I (1516-1558), who, in contrast to her celebrated younger sister, Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), has gone down in history as one of the most violent and repugnant rulers to ever take the English throne. And her father, Henry VIII, was a tough act to follow.

Mary I's bloodthirsty reputation in popular consciousness is ensured almost exclusively by the merciless execution of 287 Protestants, whom she ordered to be burned at the stake as part of the Marian Persecutions during her five-year reign (per Smithsonian Magazine).

However, as The History Press points out, the common belief that Mary was the bloodiest of all monarchs of the period is tentative at best, and in recent years historians and academics have been at pains to reassess and contextualize the reign of one of England's most misunderstood monarchs. It has been pointed out, for example, that the reign of Henry VIII himself was far more violent, with the contemporary chronicler Raphael Holinshed claiming that some 72,000 people were put to death by his royal decree (per The History Press). In fact, it is increasingly argued that Mary I's tumultuous reign was blighted both personally and politically by the actions of her father. Here is how historians view "Bloody" Mary's place in history today.

The trauma of Mary I's illegitimacy

Mary was the eldest of Henry VIII's children, and the only offspring from his first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon (pictured), to survive to adulthood. According to Biography, Mary was a highly intelligent child, a natural scholar who quickly developed a passion for the subjects she was tutored in, most notably music and languages. But from a young age, Mary also developed a deeply religious side, the result of the Catholic faith she was baptized into shortly after her birth. Mary's prodigious assimilation of her faith was admirable, but it was also soon to become the source of much pain in her early life and would come to shape her eventual reign as Queen of England and Wales.

While Mary was still a teenager, Henry began to demand that the Catholic Church declare his marriage Queen Catherine void, and offer him an annulment. When they refused, Henry split with Rome and formed his own Church of England, installing himself as Head, and divorced Catherine to marry one of her maids, Anne Boleyn. Per Biography, after Boleyn gave birth to her first child — the future Elizabeth I — the new queen lobbied for Parliament to pass an act that would ensure her daughter's royal lineage. As such, Mary became officially illegitimate, a heart-rending event in her young life that would see her become alienated from her father and from the wider society for many years (per Smithsonian Magazine).

Mary I's defeat of Lady Jane Grey

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Mary stood by her Catholic beliefs throughout her father's marriage to Anne Boleyn, and remained a pariah until after Boleyn's beheading in 1536. But though Mary eventually reconciled with her father, she was once again betrayed when, upon the death of Henry VIII in 1547, the crown was passed to her 9-year-old half-brother, Edward, Henry's son from his third marriage, to Jane Seymour. Mary was appalled by the work of Edward VI — or, rather, his advisors and ministers — who became a Protestant reformer who sought to erase Catholicism from public life.

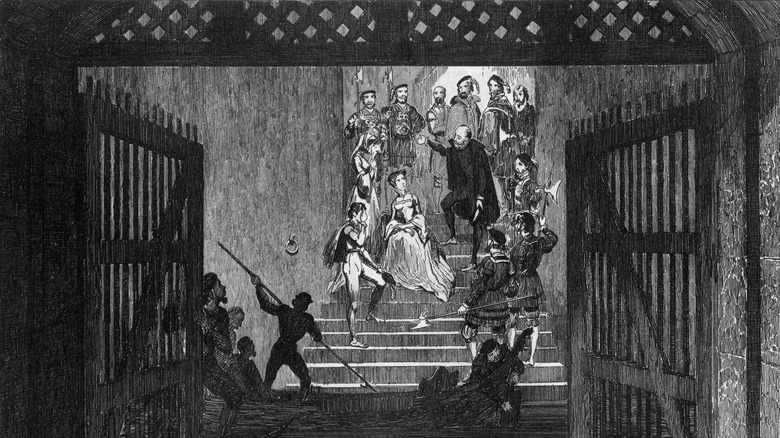

Edward died of a pulmonary illness when he was just 15, after which his supporters connived to install another Protestant, Lady Jane Grey (pictured), as Edward's successor, though as Henry VIII's eldest surviving daughter Mary was next in line to the throne. But the erstwhile princess was compelled to battle for what she believed to be her divine right. Per The History Press, Mary made her base at Framlington Castle in Suffolk, where she amassed enough troops to challenge Grey for the throne. She seized London to great fanfare and claimed her legitimacy, acceding to the throne in July 1553.

Though it is tempting to portray Mary's use of military might in becoming queen as a ruthless smash-and-grab, historians now argue that her decisive actions in response to her sidelining were an unexpected success that single-handedly ensured the survival of the Tudor dynasty.

Why did Mary I lock Princess Elizabeth in the Tower of London?

Despite Mary I's popularity at the time of her coronation (per The History Press), she soon attracted many enemies. Not only was she bound by her religious convictions to overturn many of the strident Protestant legislation that had been passed by Edward VI — Edward and his advisors had made the Latin Mass and the use of holy relics illegal — she also courted more controversy with the Act of Parliament that ensured a ruling queen had the same sovereign power as any king, and as a result of her proposed marriage to the Catholic Philip II of Spain.

As such, she faced being overthrown by a popular movement known as the Wyatt Rebellion, a Protestant uprising which sought to block the marriage and to install Princess Elizabeth on the throne. When the rebellion was crushed, Mary had its leaders executed and wanted her sister taken to the Tower of London for questioning.

It has become a famous historical tidbit that Mary heartlessly imprisoned her own sister in the Tower, but according to The Tudor Society, Mary's hand was forced in light of the rebellion. Elizabeth was reportedly kept in comfort in the complex's royal palace, was allowed to walk in the grounds, and was released after two — albeit terrifying — months. It may have served Mary well in preventing further uprisings to have had her half-sister disposed of, but instead she kept her close at hand as the only other surviving Tudor.

Religious persecution under Queen Mary I

The reign of Mary I is today defined by her brutal executions of Protestants, known as the Marian Persecutions. But was Mary's campaign of burning at the stake as extraordinarily sadistic as it now appears? Historians now argue that such a horrific method of death served a number of religious purposes. Mary herself claimed that such a shocking public display was "so used that the people might well perceive them not to be condemned without just occasion, whereby they shall both understand the truth and beware to do the like" (via Smithsonian Magazine) — that such displays would scare people into returning to Catholicism.

The most famous victim of the Marian Persecutions was Thomas Cranmer, who had been Archbishop of Canterbury to both Henry VIII and Edward VI. Per The Smithsonian Magazine, Cranmer had been planning to enact a similar campaign against Catholics, but had fallen from prominence following Edward's early death. Academics now argue that the religious violence of the Tudor age wasn't simply the reserve of one faction or monarch; rather, "[t]hat obdurate heretics, who refused to recant, should die was an all but universal tenet," as historian Sarah Gristwood argues (quoted by Smithsonian). As disturbing as it is, some historians even argue that burning as a method of death was not simply brutal for its own sake, but was intended, through foreshadowing the fires of hell, to allow heretics one more chance to repent and in their final moments embrace the true faith.

Queen Mary I was overshadowed by her successor

Queen Mary I died tragically November 17, 1558, after a lifetime of ill health, possibly from cancer, according to History Extra, amid great personal and political turmoil. Her eventual marriage to Philip II of Spain had remained deeply unpopular, despite her suppression of the Wyatt Rebellion, and with the Marian Persecutions remaining prominent in the public mind, it seemed that her reign was one of especially destructive religious conflict (per World History). Nevertheless, much of what came to define Mary's time on the throne she inherited from her immediate precursors, Edward VI and Henry VIII, who similarly dealt in religious division and shed blood in the process.

At the time of her death, the reign of Mary I was considered a failure, and the coronation of Elizabeth I was considered the dawning of a new "golden age." But as The History Press notes, Elizabeth I owed much to her much-maligned predecessor, who, in wrestling the crown from Lady Jane Grey, saved the Tudor line and allowed for Elizabeth to claim legitimate sovereignty. Not only that, but many of the successes that were classically attributed to Elizabeth's reign had their roots in the actions of Mary, such as fiscal, educational, and medical reforms, and — most notably — the immense strengthening of the English navy, without which Elizabeth would never had enjoyed her greatest victory: the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.