Most Dangerous Lizards And Turtles In The World

From snakes to the legendary dinosaurs, reptiles are a notorious subsection of the animal kingdom that has produced some of the most deadly and terrifying creatures to have ever walked the earth. Talons, fangs, whip-like tails, and venoms are all hallmarks of these cold-blooded creatures whose slitted eyes and smooth scaled skin have been the object of repulsion and fear for millennia. Lizards are also among the most diverse subgroups of reptiles, producing everything from the soft and docile totem of Hawaii, the gekko, to some of the most massive and terrifying reptilians to walk the earth since the dinosaurs — monitor lizards, among them the infamous Komodo dragon.

Turtles too, despite being mostly thought of as slow-moving terrarium pets, have produced their fair share of formidable reptile species capable of munching through flesh and bone, and even swarming prey much larger than themselves. Here are some of the most dangerous lizards and turtles that have ever lived, most of which still walk the earth to this day.

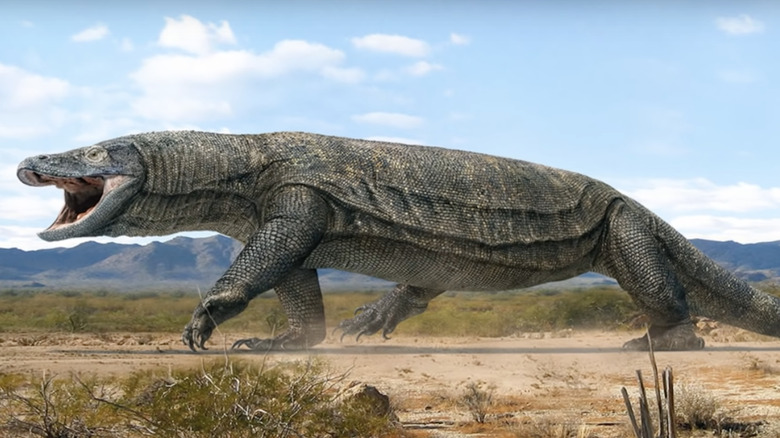

Komodo Dragon

As the story goes, Komodo dragons got their name when western scientists near Australia caught rumors of dragon-like lizards inhabiting the Lesser Sunda islands of Indonesia (Komodo in particular). As outlined by The San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Library, Komodo dragons weigh upwards of 300 pounds and reach lengths of 10 feet, easily making them the world's largest and heaviest lizard. And while size doesn't always equate to lethality, the Komodo dragon is easily the world's deadliest lizard too.

As with most monitor species, Komodo dragons possess a formidable combination weapon of serrated teeth dripping with toxic venom. And while Komodo National Park guide Mr. Safina claims they also possess jaw strength enough to "snap a man's leg in two," it's the venom that makes these lizards so formidable. As described by National Geographic, Komodo dragons are patient hunters, ambushing prey and wounding them with lightning-quick gashing bites. Most victims walk away from the initial attack, but then the venom kicks in, introducing anticoagulant agents that lead to massive blood loss, shock, and finally death. Scarier still, Komodo dragons aren't shy about attacking humans. Even celebrities aren't safe, as one Los Angeles Zoo dragon demonstrated when he snacked on the foot of journalist Phil Bronstein, then married to Sharon Stone.

Alligator Snapping Turtle

Save, perhaps, a certain team of crime-fighting comic book heroes, turtles aren't generally what most people think of when deadly comes to mind. Residents of the southeastern United States, however, know that salmonella isn't the worst everyone's favorite slow-moving underdog can dish out. One of the south's many notoriously hazardous fauna, alligator snapping turtles are a formidable reptile with a prehistoric look, aggressive demeanor, and one of nature's nastiest bites.

Though often exaggerated to have a 1,000-pound bite force, an alligator snapper's bite is actually less than that of the common snapping turtle. At an average of 35.5 pound-force, that's over 250 pound-force less than that of an adult human, as per The Forest Preserve District of Will County. Nonetheless, as reported by ThoughtCo, that's more than enough force to sever fingers, aided in large part by the animal's sharp mandible beak. Additionally, all four of this turtle's limbs sport bear-like claws, which, as Tufts Wildlife Clinic points out, are plenty sharp enough to cause deep gashes. Despite their weaponry, appearance, and nasty reputation, many experts, including the reptile and reptile ecosystem protection non-profit, The Orianne Society, insist that alligator snappers only attack when cornered and provoked. In fact, though not legal everywhere, people have been known to keep alligator snappers as pets.

Common Snapping Turtle

The common snapping turtle is divided into three morphologically similar species: the common snapping turtle of North America, the South American snapping turtle, and the Central American snapping turtle (via Sciencing). Like its cousin, the alligator snapping turtle, common snappers are a very old species that have gone mostly unchanged since they made their debut 90-million years ago, as per Finger Lakes Land Trust (FLLT), and it shows in their ancient, dragon-like appearance. But while common snappers don't get nearly as big as alligator snappers, they're quite easily the more dangerous of the two turtle types.

Just like alligator snapping turtles, common snapping turtles carry a well earned reputation as an animal best left alone. While both turtles have an often exaggerated bite strength dwarfed by many less notorious species (via the Journal of Evolutionary Biology), each is still fully capable of biting clear through human muscle and bone. Common snappers possess the stronger bite of the two, but it's really their neck that makes them so dangerous. As FLLT outlines, common snappers have a long and dexterous neck, referenced by their Latin name, Chelydra Serpentina ("snake-like-turtle"), allowing their head a wide range of motion.

Gila Monster

Until a 2005 research paper concluded otherwise, it was long thought that only three lizard species –- all native to North America — possessed venom: the Mexican and Guatemalan beaded lizards and their larger Northern relative, the gila monster. By far the most notorious of the three, the gila monsters have inspired folk legends for generations, even becoming the subject of a 1950s creature feature wherein a 50-foot version attacks a small Texas town. In truth, the real life monster grows to a more modest 22 inches and weighs 5 pounds, a scale well below most other dangerous lizards. Additionally, despite a reputation that says otherwise, gila monsters rarely attack humans, and, according to the Wilderness Medical Society, no human has died from a gila attack since the 1930s. Nevertheless, you wouldn't want to run into one in a dark desert alley at night.

An old adage claims that, if bitten, a gila monster's jaws will remain firmly clamped until sundown (from the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum), which, despite poetic exaggeration, is actually somewhat true. Unlike snakes, which inject venom into their victims directly through hollow fangs, gila monster venom drips from glands near their gums, before being essentially chewed into their victims as they maintain a firm and severely painful bite lasting several minutes. And the damage is far from over once the lizard finally releases its bite: As described by the Wilderness Medical Society, envenomation symptoms can approximate a bad flu, along with swelling, drop in blood pressure, and sweating.

The Coal Turtle

When it comes to being deadly, few living animals can compete with their ancient relatives, many of whom lived in severely more hostile times in Earth's history and had to adapt. Evolutionary gigantism is one such adaptation that has occurred again and again, showing up at one time or another in many versions of animals that are familiar today. Turtles have many such extinct relatives, the largest of which, according to Live Science, Stupendemys geographicus, measured almost 8 feet and weighed an approximate 2,500 pounds. Evidence suggests Stupendemys was omnivorous, and like most giants it probably wouldn't have been wise to get into a tussle with one. But its slightly smaller cousin, Carbonemys cofrinii or Coal Turtle, was definitely trouble.

As reported by the Smithsonian Insider, Carbonemys was discovered in Columbia in 2005 and was so named the coal turtle because of its discovery location inside an abandoned mine. Only marginally smaller than Stupendemys at roughly 5 foot, 7 inches in length, with its head being about the same size as a football. Like other dangerous turtles, what really set the coal turtle apart was its large powerful jaws. Closely resembling those of modern-day snapping turtles, the coal turtle was likely something of an apex predator, eating everything it could fit in its beak, including some of the ancient crocodilian species it shared space with.

Iguanas

According to the Humane Society of the United States, iguanas were once the number one pet reptile in the U.S. While this is no longer the case, thanks in no small part to restrictions and bans such as those enacted by the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission, iguanas remain a fairly popular pet within the U.S. and beyond. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, roughly 30 species of iguana exist, and while the species most commonly kept as a pet, the common green iguana, is naturally more docile and tolerant of humans, all iguana species are actually pretty dangerous lizards.

Across the iguana family, that danger mostly comes from being bitten, which aside from being incredibly painful also commonly causes swelling and excessive blood loss. Prior to 2005, popular scientific consensus was that only a handful of lizards were venomous, placing the blame for most adverse reactions to lizard bites squarely on bacterial infections. That year, a team from the University of Melbourne published new findings indicating that, in fact, most large lizard species produce venom and were capable of inducing mild envenomation in humans (via New Scientist). Additionally, as a mostly arboreal (tree climbing) animal, many iguanas also come equipped with sharp claws on all four feet. While these are no more (or less) sharp than those of a house cat, iguanas naturally carry salmonella, which can become transferred via its claws, leading to painful and dangerous bacterial infections (from Reptile Valley).

African Helmeted Turtle

Exotic pet collection has been of human interest since at least Ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire. Whether for intimidation, aesthetic appeal, or a marker of status, sometimes the desire to own a rare breed all comes down to a smile. Such is the case for the African helmeted turtle, a species found throughout much of Sub-Saharan Africa across and even Madagascar (from Africa Freak). A species of side-necked turtle, the African helmeted turtle's other major source of appeal comes from its family's unique form of tucking, which according to Encyclopedia Britannica, involves swinging its head beneath the overhang of its shell, rather than retracting it straight back into its body. Amongst other turtles, nothing about the African helmeted turtle is especially dangerous, and in fact they pose no known threat to humans at all. Birds and smaller mammals, on the other hand, should maybe watch their backs.

Unlike any other turtle species, and few other reptiles, African helmeted turtles are occasional pack hunters, notes Turtles of the World (via animals.jrank.com). This unique behavior has earned them the nickname "Crocodile Turtle" due to the specific way in which they cooperatively take down their prey. When large enough population densities occur, African helmeted turtles will collectively latch on to animals much larger than themselves, drag them into bodies of water, drown them, and then tear their lifeless bodies apart with their beaks and forelimbs, not unlike a crocodile.

The Mexican and Guatemalan Beaded Lizards

Along with the closely related and infamous gila monster, Mexican and Guatemalan beaded lizards were once the only lizard species thought to produce venom. While it is now understood that many lizard species produce venom, beaded lizard venom is some of the most deadly. Despite bites being rare, and actual envenomization being even rarer, a 2003 report in the National Library of Medicine details how serious a beaded lizard bite can be. In the report, a 40-year-old man was hospitalized with symptoms of vomiting, dizziness, and severe pain. Shortly after being admitted, the patient was put on oxygen supply before being transferred to intensive care where he spent the next day recovering.

Though no anti-venom exists for any beaded lizard, modern medical practice has dramatically reduced the likelihood of fatality from being bitten by any of these three lizards. And while Animal Diversity Web claims beaded lizards are more aggressive than gila monsters -– especially at night when they tend to hunt and hostile interactions with humans are more likely to occur — all known instances of being bitten in recent history have come as a result of a lizard being handled, or intentionally provoked. Regardless of these caveats, a rare bite could quickly become fatal under the wrong circumstances, so it's best to avoid the possibility of a bad interaction when possible.

Perentie

Among the world's most dangerous lizard species, most belong to the monitor lizard family, which includes the rightfully notorious Komodo dragon and what was possibly the largest venomous animal to have ever lived, megalania. Commonly kept as exotic pets –- despite all monitors being fairly dangerous regardless of type — a number of species are well known outside of science. Perentie, a reclusive Komodo dragon cousin native to the Australian outback, is not one of them, which is a shame considering they are nevertheless a fascinating species and easily one of the most dangerous.

According to Love Nature, perentie are apex hunters and Australia's largest lizard. Their success in conquering the outback comes down to a comprehensive array of offensive and defensive tools that include desert-colored camouflaging, a powerful and venomous bite, a breakneck 25-mile-per-hour gait, and a tail-whip capable of breaking leg bones. While this make the perentie more than capable of surviving on its regular diet of small rodents and other lizards, these adaptations are also something of overkill and have allowed them to supplement their usual fare with much more unlikely prey, such as two of Australia's most well known animals: dingos and red kangaroos. As a reclusive animal, and one that typically lives well beyond the borders of most Australian settlements, perentie rarely come into contact with humans. All the better, as this monster lizard might otherwise decide to include us on its menu as well.

Loggerhead Sea Turtle

Snapping turtles are popularly thought to have the strongest jaws of all turtles, terrapins, and tortoises but are in fact surpassed by a surprising number of their cousins, including the charismatic Loggerhead sea turtle. Found in oceans and seas around the globe, Loggerheads can grow up to4 feet long and weigh as much as 400 pounds. According to the World Wildlife Foundation, they are directly related to a group of turtles that has been around for more than 100 million years. Makes sense that Loggerheads would still be around, since they use their massive heads and incredibly powerful jaw muscles to eat all kinds of crunchy foods, such as clams, sea urchins, and basically any mollusk it can find (via CaliforniaHerps).

In a research article published in the Journal of Experimental Biology in 2012, researchers found that the bite force of Loggerheads was relative to their size. Meaning that, as Loggerheads grow, their bite force grows, allowing them to ingest larger, harder food, which in turn allows them to grow even larger. Larger turtles can have a bite force as strong as 100 pounds-force. Pair that powerful jaw with the Loggerheads much larger size, and it's easy to imagine a finger, or worse, getting chomped off by those unlucky enough to swim into Loggerhead territory on a bad day.

Megalania

It's no secret Australia is home to some of the world's scariest creatures, so it should serve as no surprise that the country's ancient past was home to giants, namely the fearsome Megalania. These ancient monitor lizards — essentially jumbo-sized Komodo dragons — may have gotten as large as 16 feet and been as heavy as 1,300 pounds, making them big enough to take on large prey. According to the Australian Museum, this may have even included kangaroos, the remains of which have been found near Megalania bones.

This isn't great news for Australia's earliest humans, the Aboriginal peoples, who may have had to live around these massive monitors. Megalania emerged during the Pleistocene period more than 2.5 million years ago, but a 2015 study conducted by the University of Queensland (via Quaternary Science Reviews) was able to date bone fragments from a large, ancient lizard as being roughly 50,000 years old. And while these remains may have been from a large Komodo dragon, there is a chance they were from a Megalania.

Like modern monitor lizards, Megalania was likely venomous (making it the largest venomous animal of all time), which would have caused some pretty painful deaths. It's unclear exactly what caused its extinction, but like many of history's larger creatures it likely died off due to a lack of food, though it's also been suggested that humans were to blame.

Crocodile Monitor Lizard

It's no secret that crocodiles are not to be trifled with, so it stands to reason that any animal named after these saltwater terrors would be formidable in its own right as well. While its rounded snout and long tail are the primary reason for the nickname "tree crocodile," there's no denying the crocodile monitor of New Guinea poses its fair level of danger if not handled with care. (Incidentally, the physical similarities with crocs are prevalent enough that the Singapore Government has a breakdown of their differences available via their national park's website.)

Like other monitor lizards, crocodile monitor lizard's have long, dexterous claws, perfect for climbing into trees. Unlike other monitor lizards, these tree dwellers can often be seen hanging from branches by their powerful back legs, notes Animalia. As with the rest of its family, the crocodile monitor is venomous, meaning a closer interaction could end in a meeting with those sharp, poisoned fangs, and a quick trip to the emergency room.

Though primarily scavengers, crocodile monitors will hunt when necessary, in their own peculiar way. While many predators — including its Komodo cousin — prefer a sneakier, stealthier attack, crocodile monitor lizards prefer to face their prey head on, a move that's sure to be intimidating to anything on the wrong end of it. While this is mostly bad news for birds and small mammals, Animalia reports they've been known to hunt pigs, deer, and even hunting dogs.