Why Andrew Johnson Pardoned Abraham Lincoln's Attempted Assassin

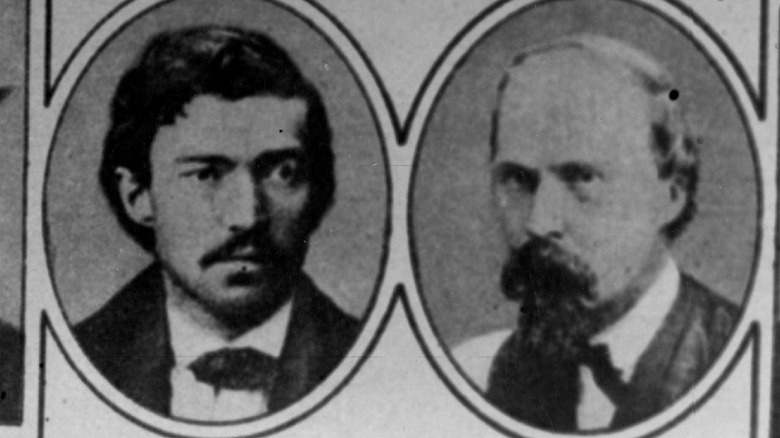

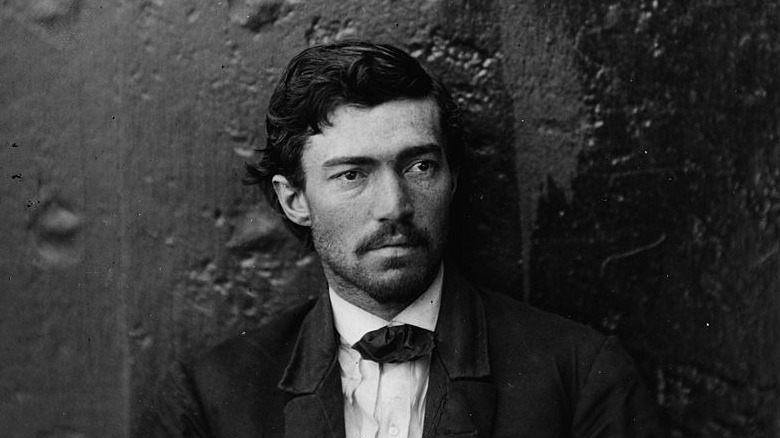

On March 1, 1869, President Andrew Johnson issued a pardon to Samuel Arnold, one of the men found guilty of a conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

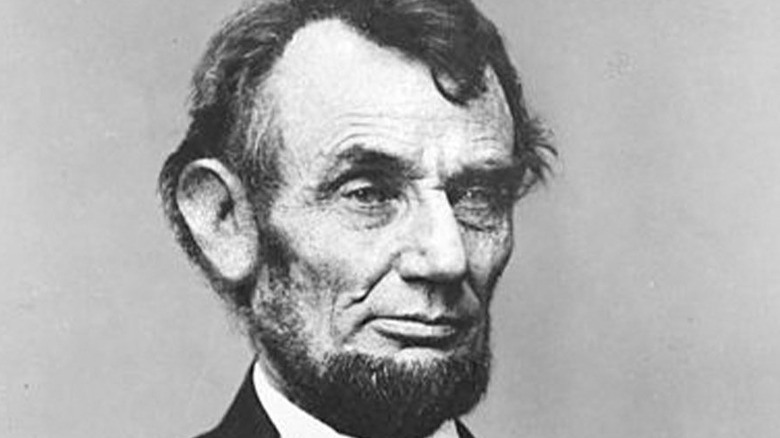

President Johnson did not give any explanation for this act of mercy and it is impossible now to know exactly why he pardoned Arnold. Historians have offered a few possible hypotheses. The first possible reason is that there is actually some debate as to whether Arnold was even a part of the assassination. As explained by Spartacus Educational, there was certainly concrete evidence that backed up that Arnold had been a part of a plot to kidnap President Lincoln in March of 1865. The plan was to ransom the president for Confederate prisoners. The scheme never managed to materialize due to Lincoln's changing schedule, and Arnold appeared to abandon the plans to target Lincoln. Around a month later, though, one of the members of the original kidnapping plot, John Wilkes Booth, instead shot President Lincoln in the head while he and the First Lady were watching a performance of "Our American Cousin" at Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C. Though letters appeared to offer definitive proof that Arnold has been involved with the conspiracy to kidnap Abraham Lincoln, the evidence for his involvement in the later assassination was much flimsier.

According to Famous Trials, Arnold's attorney, Walter Cox, argued that Arnold had "backed out from this insane scheme of capture," evidenced by the fact that the former Confederate soldier left Washington for Virginia in March, nearly a month before the assassination. A military tribunal nevertheless found Arnold guilty and sentenced him to life in Florida's Fort Jefferson — now known as Dry Tortugas National Park.

Arnold may have benefitted from a popular friend

However, another potential reason for the pardon may have been the public attention received by Arnold's co-conspirator and cellmate, Samuel Mudd. Mudd was a doctor from Maryland who had met John Wilkes Booth just once before the assassination. However, Mudd had set Booth's broken leg when the murderer was on the run following the Lincoln assassination, essentially sealing his fate as a co-conspirator.

Though Mudd claimed that he only helped Booth because of his position as a doctor, he was still found guilty and sentenced to a life of hard labor at Fort Jefferson. Mudd and Arnold had served several years in a cell together when yellow fever ripped through Fort Jefferson and killed the prison's physician, Joseph Sim Smith. As a result and due to his training, Mudd was placed in charge of medical care at Fort Jefferson — and found a great deal of success in treating the sick men due to his focus on constant care and diligent cleanliness, rather than using the traditional method of simply quarantining the ill, per Smithsonian Magazine.

One grateful soldier wrote about his experience and petitioned President Johnson to offer Mudd clemency in return for his work. Mudd's wife publicized the petition and it quickly garnered widespread support and resulted in his eventual pardon. Though Arnold played no part in the medical team, the fact that he was present during the epidemic and Mudd's cellmate might have earned him clemency-by-association, as he was given a pardon as well less than eight weeks after Mudd.

President Johnson was focused on uniting the country

Last but not least, historians have also pointed out that President Johnson was focused on uniting the country after the brutal Civil War — even if it meant alienating Republicans in the process. For example, he issued a proclamation on May 29, 1865, that offered amnesty to a majority of Confederate officials and soldiers, provided they swear allegiance to the United States and free any slaves that were still in bondage. Though Johnson claimed that the proclamation was necessary to focus on punishing the small group of leaders of the Confederacy, it is nevertheless considered one of the most controversial uses of a pardon in Presidential history, as noted by the University of Virginia's Law School.

The initial pardon excluded fourteen groups of Confederates to target the ringleaders of the rebellion. However, on September 7, 1867, President Johnson decided to expand the pardon in an effort to hasten the Reconstruction efforts. He continued to increase the reach of the pardon, and by Christmas of 1868, almost all former Confederates were forgiven, per The Reconstruction Era.

Considering Johnson's pattern of leniency, it is not improbable to guess that the president wanted to finish his policy for clemency before he left office.