The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Explorer John Smith

Captain John Smith, otherwise known as that English guy who was saved by Pocahontas, was an English explorer and author. The Pocahontas incident, though — that's why he's famous, right? Actually, it turns out Smith had a lot of wacky things going on in his life, even beyond his leadership at Jamestown and capture by the Powhatan tribe. Born in England, Smith became embroiled in wars in Austria and France as a young man and was captured into slavery (via History). After that debacle, he was invited on the Jamestown voyage. Everyone knows how that turned out! And in his later years, Smith went back to England and eventually began to write about his adventures.

Throughout his life, John Smith emphasized the value of hard work. He was a pioneer on several counts and sought to lead by example; for instance, he captained three mapmaking expeditions throughout New England. Though he was later known for stretching the truth of his voyages, Smith made a major impact on the founding of New England as a region and culture, not to mention the founding of the United States as a whole.

Born in England, went to France

John Smith was born at the beginning of January in 1580. According to the National Park Service, he was baptized at St. Helena's Church in Willoughby, Lincolnshire. His father, George, was a farmer who both owned and rented land, and his mother's name was Alice. Young John Smith attended local grammar schools, but always longed for adventures. When he was 13, he ran away to be a sailor, but his father brought him back and made him be an apprentice to a merchant instead. After his father's death when he was 16, Smith took the opportunity he had always wanted and left England, according to History. He joined English soldiers voluntarily fighting the Spanish for the cause of Dutch independence in France and the Netherlands.

Smith briefly returned to England — now a full-blown soldier — before making trips to France and Scotland. Eventually, though, he settled back into the land where he was raised — literally. Smith built a rough cabin in Willoughby and lived off the natural area around him. For a time, Italian nobleman Signore Theodore Paleologue stayed with Smith to help improve his jousting and horsemanship skills. After this training, Smith was ready for his next adventure, which he would join very soon: working as a pirate in the Mediterranean.

John Smith fought for the Holy Roman Empire

By 1600, when he was 20 years old, John Smith served as a pirate in the Mediterranean, writes History. He earned 500 gold pieces for his work, which allowed him to travel through Italy, Croatia, and Slovenia, making his way to Austria to join the fight with the Holy Roman Empire against the Ottoman Turks. At this point in his life, Smith just couldn't stay away from war — not to mention risk. From the 16th to the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire were constantly at odds due to piracy, land grabs, and religious wars. This specific conflict was known as the Thirteen Years' War; Smith joined up in the middle, and the clash ended in 1606, per New World Encyclopedia.

Smith earned the rank of captain during the Thirteen Years' War, which he carried proudly throughout the rest of his life. The Prince of Transylvania gave Smith a title and coat of arms, using three heads of Turks he killed in jousting tournaments. His motto was in Latin: "vincere est vivere," or "to conquer is to live," writes the National Park Service. Evidently, John Smith was an accomplished leader and soldier by this point in his life.

John Smith was sold into slavery

In 1602, John Smith was captured in battle in Transylvania and sold into slavery. He was forced to march nearly 600 miles to Constantinople, where he was presented as a gift to his owner's fiancee, Charatza Tragbigzanda, writes the National Park Service. As Smith recalled later, Tragbigzanda fell in love with him and sent him to work for her brother in a fruitless attempt to convert him to Islam.

Tragbigzanda's brother Tymore treated Smith badly, forcing him to shave his head and wear an iron collar around his neck. During a particularly brutal beating, Smith murdered his owner and proceeded to steal his clothes and horse. While traveling, he met a Russian couple who helped him get his bearings. He later wrote about this experience and referred to the woman, Callamatta, as a "good lady."

John Smith traveled through Russia, Ukraine, Germany, France, Spain, Morocco, and Poland on his way back to England. One writer estimates his journeys during those years added up to 11,000 miles. Smith finally reached home in 1604, though he didn't linger there long.

Travels to America

Word of John Smith's prowess as an adventurer had reached Great Britain. More specifically, a man named Captain Bartholomew Gosnold — who wanted to found an English colony in the New World's Virginia — took notice of Smith. After returning home from mainland Europe, Smith was invited to join the newly-created Virginia Company of London's voyage to establish said colony. According to the National Park Service, the company was granted a charter for the endeavor from King James I on April 10, 1606.

Three ships (the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery) with 104 settlers set off in December 1606 (via History). The voyage made it clear that Captain Gosnold may have been slightly too hasty in choosing Smith as a settler. During the months-long journey Smith was accused of mutiny, barely escaped a hanging, and arrived in the Americas as a prisoner of his entire party. The settlers' minister, Reverend Robert Hunt, assisted with his rehabilitation, and Smith eventually joined the leadership council (with six others) as he was always meant to, despite his prior behavior.

Early Jamestown

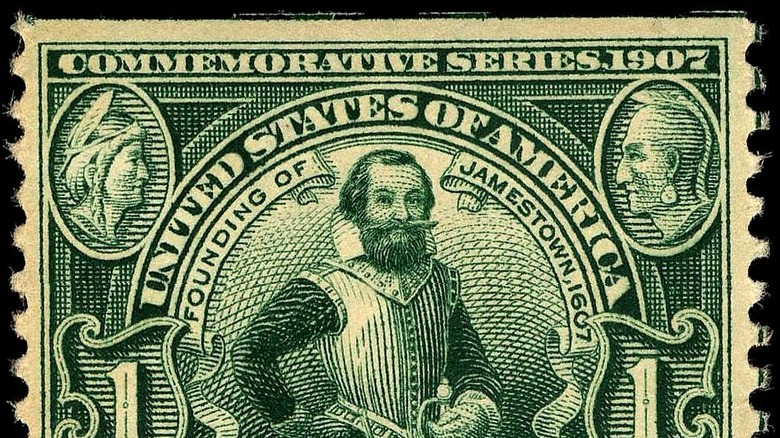

The settlement that became known as Jamestown was officially established on May 13, 1607. It was named in honor of King James I, then king of England. It was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas and eventually became the first of thirteen colonies that broke away from Great Britain's control nearly two centuries later.

Jamestown was in Virginia on the banks of the James River, which was also named for the king. In the early 1600s, Virginia wasn't the state it is known as today. Instead, it was the name the Englishmen gave for the entire northeast coast above then-Spanish Florida, writes History. It was named for Queen Elizabeth I, the so-called Virgin Queen. The Virginia Company's goals in the region were to seek gold, silver, and a water route west to the Pacific Ocean for trade purposes.

In early 1607, however, Jamestown had a hard few months. Food shortages, unhealthy drinking water, squabbles over leadership, fights with local Native Americans, and disease all contributed to a difficult existence, writes the National Park Service. To make a bad situation worse, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold died during this time, so Jamestown was without a founder and innovator.

Experiences with the Powhatan tribe

Just before winter set in, John Smith was reduced to stealing food for the colony from the nearby Powhatan tribe. In December 1607, he was captured by a Powhatan hunting party and made to travel to various Powhatan villages. Eventually, Smith was brought to Chief Powhatan, also known as Wahunsenacawh. Smith later wrote of the incident, claiming that he was rescued by Pocahontas, the chief's young daughter. Still, historians and anthropologists believe Smith may have misinterpreted the event, and suggest it might have been an adoption ceremony, writes the National Park Service.

Smith was released shortly afterward and made his way back to Jamestown with assistance from the Powhatan tribe. By this time, only 38 of the original 104 settlers were still alive. But by January 1608, more settlers had arrived to make up the numbers. The Powhatan tribe sent food to help the new settlers, but an accidental fire caused most of the main fort to burn down. As a result, many of the new settlers died soon after their arrival due to the lack of shelter and the extreme cold that year.

As a leader of the rapidly dwindling population of Jamestown, Smith focused on the colony's immediate needs of food and shelter. According to his writings, many other colonists were mad for gold. Over the next few months, more settlers and food arrived, and the colony was settled enough that Smith felt able to explore more of the Chesapeake Bay.

Exploring the Chesapeake Bay and making progress

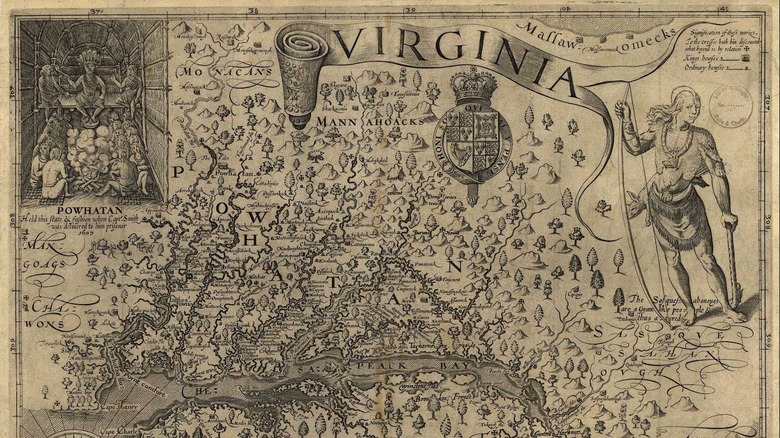

By September 1608, John Smith was encouraging farming, discipline, and defenses for the settlement, writes Historic Jamestowne. He was the president of the council for the colony and instituted a policy that everyone work — or they would starve. Smith also led two mapping expeditions of the local Chesapeake Bay, though he was nearly killed by a ray on the first expedition. He and his team covered 2,500 miles of the Chesapeake, including the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. His maps of the area included elements he thought important, such as Native American villages (via History).

Smith supervised the building of the first well in Jamestown's fort, as well as the repair of several buildings. Along with the well, archeologists were later able to trace the expansion of the fort, which was designed so that it had five sides (via Historic Jamestowne). But in late 1609, Smith was injured after a mysterious gunpowder incident while sleeping on a boat on the river. He set sail for England in October of the same year and never returned to Virginia. Smith's strong leadership skills undoubtedly helped the colony survive overall, but he may have burned bridges with others while doing so. Therefore, his injury might have been intentional and dealt by an enemy. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Smith was ultimately forced out of Jamestown due to his harsh style of leadership.

Mapping and naming New England

After he left Jamestown, John Smith began to map New England in multiple ways. Back in England, he published a map of Virginia in 1612. Two years later, he was able to make a journey to the North American northeast to map the area. Smith considered the maps of the area he had from others to be worse than useless, saying they were "so unlike each to other; and most so differing from any true proportion, or resemblance of the Countrey, as they did mee no more good, then so much waste paper, though they cost me more" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

With a team, Smith mapped the shores of what is now Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, writes History. They traversed 350 miles, working from the Bay of Fundy all the way to Cape Cod. On his published 1616 map, Smith also effectively named the region New England, and the map was published with his book "A Description of New England." Historians consider it remarkably accurate for the time, especially considering what crude tools Smith was using.

Smith wanted to return to the region and form another colony, but while sailing back to New England in 1615, he was captured by French pirates and imprisoned for several months. Regardless, Smith's mapmaking expedition helped sell North American to the English, and his work influenced Britain's colonialism of the area in the coming centuries.

Capture, return to England, and reminders of past wrongs

On his way home from New England, John Smith was captured by French pirates. When he finally did regain his freedom to make his way back to England several months later, he couldn't find anyone to pay for a new voyage to the Americas. Smith was heavily committed to working and living in North America for as long as he could — even soon after months of presumably ill treatment from pirates.

Chief Powhatan's daughter Pocahontas — by then married to English tobacco farmer John Rolfe — met Smith at some point when they were both in England. She was angry at Smith's ill-treatment of her father and her tribe, writes the National Park Service. Smith had actually written to Queen Anne to commend Pocahontas for her actions in helping the English in Jamestown. However, before he left Jamestown, Smith was not able to quell the rising tensions between the colony and the Powhatan. Those tensions erupted soon after he left, with Smith unable to contribute much from afar.

John Smith wrote of his adventures

Permanently back in England, John Smith began to focus on writing about his adventures. In 1624, he published "The Generall Historie of Virginia," according to History. He also published "The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith, in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America" in 1630. Notably, his early work on the subject stimulated English interest in the Americas and provided later historians with vital primary sources for American history.

As one of the first Englishmen to sail to and live in Virginia for a substantial amount of time, Smith was qualified to write on the subject. With all of the adventures in his life, it's not surprising that he wrote books about them. According to Historic Jamestowne, he penned several volumes of his experiences on Virginian soil. Since he couldn't find a financial backer for more voyages, it's also not surprising that he fell to telling tales of the past. John Smith evidently liked it best when all eyes were either on his physical actions or his words.

Frequent exaggerator of exploits, but occasionally truthful

John Smith was known for stretching the truth in his writing, though scholars have managed to verify some of his information from Jamestown. According to The New Yorker, Smith could be considered the first American historian.

Smith often wrote about himself in the third person, and though people claimed that his stories changed every time he told them — particularly his tale regarding himself and Pocahontas — he was generally detailed. The Jamestown Rediscovery Project found various artifacts that point to a solid fort being built relatively quickly at Jamestown, which indicates that the first settlers were not as useless as Smith claimed they were in his writing. On the other hand, some of the artifacts found — like a silver ear picker — were probably not the best choices for a long, hard journey to a new land.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, John Smith named Plymouth on his 1616 map and noted that it would be a good site for a colony. It is only by pure chance that the Pilgrims landed there four years later, particularly since they were planning on landing elsewhere until the weather got in the way. Ultimately, even if he liked to talk up his exploits, Smith was knowledgeable and skilled in what he did.

John Smith's death and legacy

Even towards the end of his life, John Smith's name was still floated about as a possibility for the position of military leader for the Pilgrims in 1620. Though his maps of New England were used, he was not chosen to join the expedition, writes History.

Smith died in London in June 1631. He is well-known to Virginians today for keeping Jamestown going as long as he did. Even after his efforts at Jamestown, he continued adventuring in the Americas, creating the first accurate maps of the Chesapeake and New England regions in the process. In general, his writing about his experiences in Virginia and in the North American northeast allowed for the creation of early scholarship on the region (via Historic Jamestowne).

According to the National Park Service, one of Smith's biographers, Philip L. Barbour, wrote, quite accurately, "Captain John Smith has lived on in legend far more thrillingly than even he could have foreseen."