The Tragic Life And Mysterious Death Of Whistleblower Karen Silkwood

As of 2021, no one knows exactly what happened to activist and whistleblower Karen Silkwood. Her untimely death at the age of 28 has all the hallmarks of a tragic accident, but it's not unlikely that she was murdered to keep her silent. But then when you throw the fact that she was highly radioactive — literally — into the mix, the story seems to make less and less sense as it goes on.

But whether or not Silkwood's life is a murder mystery or an unfortunate story, what's clear is that during her time at the energy company Kerr-McGee, Silkwood tried to advocate for the health and safety of herself and her fellow workers. To her, it was almost unbelievable that the company she worked for would deliberately neglect to inform its workers of the dangers of radiation, and she refused to be complicit.

Played by Meryl Streep in the movie "Silkwood," Karen Silkwood's life seemingly reads like more of a Hollywood drama than someone's actual life story. But sometimes, the truth is even stranger than fiction. This is the tragic life and mysterious death of whistleblower Karen Silkwood.

Karen Silkwood's early life

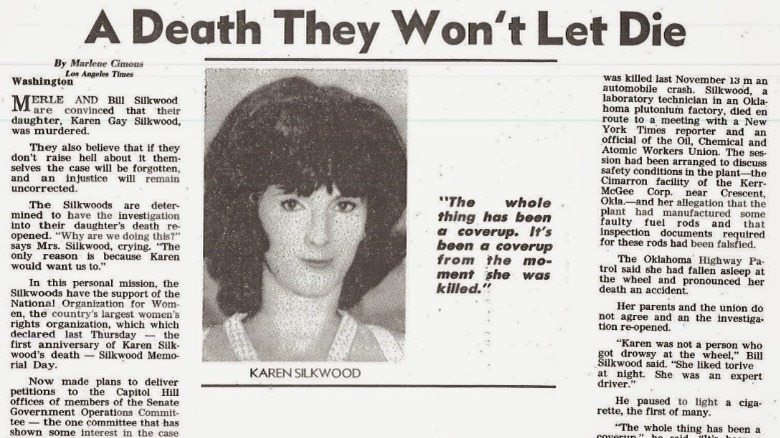

Karen Gay Silkwood was born in Longview, Texas on February 19, 1946, to Merle and William Silkwood and was the oldest of three daughters. Some sources state that Silkwood was part Cherokee, but it's unclear how substantiated this claim is. Growing up in Nederland, Texas, Silkwood became interested in chemistry during high school, and after graduating she went on to study medical technology at Lamar State College in Beaumont, winning a scholarship given by the Business and Professional Women's Club, per the Texas State Historical Association.

After marrying William Meadows in 1965, Silkwood left college and would go on to raise three children, eventually leaving Meadows in 1972. Historic Heroines writes that Meadows had offered her an uncontested divorce if she agreed to give him custody of their children, and although Silkwood initially refused, after seven years of unhappiness she agreed to an unconditional divorce if he granted her visiting rights. Leaving her husband and children in Duncan, Oklahoma, Silkwood moved to Oklahoma City.

There, after briefly working as a low-level clerical worker in a hospital, Silkwood got a job as a metallography laboratory technician with Kerr-McGee in August 1972, working at the Cimarron Fuel Fabrication Site near Crescent, Oklahoma.

Working at the Cimarron Fuel Fabrication Site

During the Cold War, Kerr-McGee worked for the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) towards creating a nuclear arsenal. At the Metallography Laboratory near Crescent, plutonium fuel rods were made for the AEC. According to Historic Heroines, radioactive plutonium pellets were inspected to make sure that they were of the correct specifications classified by the AEC. If the plutonium pellets were the correct size and didn't show any chips or cracks, they'd be made into 8-foot-long stainless steel rods. These rods were then wiped down with alcohol and given a final check in an X-ray room.

Karen Silkwood was one of the people working with the plutonium pellets themselves, randomly selecting some and checking to make sure that plutonium was "evenly distributed throughout the pellet." Silkwood also did random checks on the fuel-rod welds, making sure to run additional tests on the entire pellet lot if there were any failures and even rejecting an entire batch if "a pattern of flaws" was found.

In "Critical Medical Anthropology," Merrill Singer and Hans Baer note that Kerr-McGee offered the bare minimum when it came to training workers on how to handle plutonium. They also "routinely failed to inform them about its health hazards."

Going on strike

Three months into her new position, Karen Silkwood found herself joining the company's workers in a strike, "carrying her first ON STRIKE placard," as the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW) demanded better health and safety trainings and programs as well as higher wages from Kerr-McGee.

The strike lasted nine to 10 weeks, but in the end the strikers admitted defeat and Silkwood went back to work with a new 2-year contract. Although the strikers lost, according to "American Dissidents" by Kathlyn Gay, her experience with the strike greatly affected Silkwood: "Walking the line, living off part-time wages as a clerk in a building supply company, watching OCAW members one by one knuckle under to the pressure — all of this forged her ties with the union."

But in the end, the workers went back to Kerr-McGee with no increase in wages, no improvements in health and safety measures, and no improvements in training. And as Kerr-McGee ramped up production in the spring of 1974, "under pressure from the AEC," writes Historic Heroines, Silkwood soon noticed the consequences.

Health and safety issues at the metallography lab

In the spring of 1974, Kerr-McGee imposed 7-day work weeks with 12-hour shifts and no pause between the day and the night shifts at the metallography laboratory. This was already leading to spills and contaminations, and with a high worker turnover rate, increasingly more untrained workers were hired as well.

And according to "American Dissidents" by Kathlyn Gay, management cared little about the people they were exposing to radioactive material. "In one incident, five workers inhaled 400 times the weekly limit of insoluble plutonium permitted by the Atomic Energy Commission." And even when face respirators were given, they were often defective.

On July 31, 1974, Karen Silkwood was pulverizing plutonium pellets to make sure that they didn't contain too many other metals. After she was done, a routine check of the air-sample filter papers showed that the air Silkwood had been breathing during her shift was highly radioactive. However, according to "The Killing of Karen Silkwood" by Richard Rashke, the strange thing was the fact that the filters used before and after Silkwood's shift were clean and only the ones used during her shift were contaminated. If the air was contaminated during her shift, why wouldn't it continue to be radioactive afterwards? Silkwood provided weekly nose, mouth, urine, and fecal samples, and although all of the results came up positive, she was told that her contamination levels were deemed insignificant "by AEC standards," Historic Heroines writes.

Karen Silkwood is elected to the OCAW bargaining committee

Although Karen Silkwood was irritated and knew that negotiations for the new contracts with Kerr-McGee were starting in three months, she wasn't necessarily motivated to run for a spot on the OCAW's three-person bargaining committee. But according to "The Killing of Karen Silkwood," while Silkwood didn't campaign, she also let workers know that if she was elected, "she wouldn't turn it down." And she was elected at the beginning of August 1974, becoming the first woman to be part of the bargaining committee in Kerr-McGee's history. Working alongside the other committee members, Jack Tice and Jerry Brewer, Silkwood was assigned to focus on health and safety.

Tice soon wrote to Elwood Swisher, the vice-president of OCAW International, describing how bad conditions were at Kerr-McGee, and was "pleasantly surprised" when Swisher responded by informing him that a meeting was going to be set up with the AEC.

In preparation for the meeting, Tice was told to document everything in regards to unsafe working conditions and to be as specific as possible. These instructions were relayed to Silkwood and all through August and September she documented contamination incidents and interviewed workers. In a small spiral notebook, Silkwood kept track of a growing list of issues. "Spills, falsification of records, poor training, health-regulation violations, and even some missing plutonium," writes Women Whistleblowers.

Meeting with Mazzocchi

On September 26, 1974, Silkwood, Tice, and Brewer headed to Washington, D.C. and met with Anthony Mazzocchi, OCAW's Citizenship-Legislative Director. At the time, Mazzocchi was working on getting asbestos labeled carcinogenic and, knowing about the link between plutonium and cancer as well, Mazzocchi shared his knowledge with the committee.

"The Killing of Karen Silkwood" explains that Silkwood was furious when she learned that plutonium was carcinogenic, and that this fact had been deliberately omitted by Kerr-McGee. But Mazzocchi wasn't surprised that Kerr-McGee wasn't open with that information. If workers believed that plutonium wasn't dangerous, "the fewer the problems for the corporation." Another item of concern for Silkwood was the fact that Kerr-McGee was doctoring their quality-assurance records. And although some nuclear scientists claim that defective fuel rods aren't dangerous, no one knows exactly what could happen at best, so potential leaking fuel rods was an incredibly serious issue.

Mazzocchi decided that it was better to not yet mention the quality-assurance problem to the AEC and instead focus their upcoming testimony on the issues of health and safety for the workers. But Mazzocchi had another strategy in mind, which he shared only with Silkwood. They decided to give The New York Times the story on quality control tampering and hoped that the bad publicity would put pressure on Kerr-McGee to negotiate on health and safety issues.

Testifying to the AEC

It's not as though the committee was going to run out of things to talk about anyway. During their testimony to the AEC on September 27th, Silkwood, Tice, and Brewer gave 39 different examples of improper facilities, improper training, and failures to monitor worker exposure. The incidents ranged from a lack of routine respirator cleanings to an employee tracking contamination throughout the facility. One account even involved plutonium samples being stored in a desk drawer or a shelf for upwards of two years. Another incident alleged that when a criticality alarm went off, workers weren't permitted to respond and were instead told that it was simply a test alarm.

The AEC took note of every incident and upon reviewing the incidents, they found that 20 out of the 39 examples were "at least partially substantiated" if not wholly, according to "The Killing of Karen Silkwood." Unfortunately, the AEC didn't even undertake an investigation of these incidents until after Silkwood was dead, per "Hearing before the Subcommittee on Energy and Environment."

Karen Silkwood collects evidence

Back at the Cimarron River nuclear facility in October 1974, Silkwood started collecting hard evidence of quality-control manipulation. When studying the X-rays of rod welds, Karen Silkwood discovered that someone was manipulating the images to hide the defects. Meanwhile, Kerr-McGee continued to ignore worker health and safety. When Silkwood discovered that the gloves Wanda Jean Jung was using in her lab had holes in them, Silkwood was the one to tell Jung to get a nasal smear, while health physics supervisor Don Majors claimed that "it has some effect on genes, but you don't have near that much to worry about," according to "The Killing of Karen Silkwood." Several of the young men working with Jung were only 18 and 19 years old.

At the time, few others were on Silkwood's side. Management just saw her as someone who wanted to start trouble and even fellow union members thought that she was "rock[ing] the boat" too much. But Silkwood wasn't deterred. She continued to record contamination issues and planned to meet with the New York Times reporter in mid-November. It was also around this time that Silkwood claimed to James Noel, another worker at Kerr-McGee, that she noticed that at least 40 pounds of plutonium were missing based on existing documentation.

By mid-October, Silkwood was also having severe trouble sleeping and was developing a dependence on Quaaludes, which her doctor had been prescribing for her anxiety and depression.

The plutonium contamination

On November 5, 1974, plutonium was found on Karen Silkwood's hands after her shift at the laboratory spent grinding and polishing plutonium pellets. According to Los Alamos Science, Silkwood decided to monitor herself and found that the right side of her body measured 20,000 disintegrations per minute with the detector. And when she went to get measures at the Health Physics Office, her nasal swab showed 160 dpm. While Silkwood's gloves were replaced, no leaks could be found on the gloves and plutonium was only detected on the "outside" of the gloves. Strangely, plutonium wasn't found in the air either, as it typically would've been during a leak.

The following day, although Silkwood didn't work directly with plutonium pellets, alpha activity was once again detected on her hands again, as well as her right forearm, neck, and face. A nasal swab done on November 7th showed "significant levels of alpha activity" at 40,000-45,000 disintegrations per minute. According to "American Dissidents," other samples also showed "extremely high levels of activity."

During all of this Silkwood's car and locker were rechecked numerous times, but no alpha activity was found there. But at her apartment, up to 100,000 dpm was found in the bathroom, up to 400,000 dpm in the kitchen, and up to 2,000 dpm in the bedroom.

Karen Silkwood's contamination

Karen Silkwood, her boyfriend Drew Stephens, and her roommate Sherri Ellis were sent to Los Alamos for testing on November 11, 1974. While Ellis and Stephens were told that they had a "small but insignificant amount of plutonium in their bodies," Silkwood was told that she had "about 6 or 7 nanocuries of plutonium-239 in her lungs" and that there was also evidence of americium-241 in her lungs.

According to Los Alamos Science, the maximum permissible for workers was 16 nanocuries. But despite evidence of a fairly significant amount of plutonium in her system, Silkwood was told by Dr. George Voelz that she shouldn't be worried about radiation poisoning or cancer. When she pressed him, he continued to assure her that her reproductive abilities wouldn't be affected.

According to the Environmental Defense Institute, it's unclear exactly how Silkwood was subject to plutonium contamination, but it wasn't from "any known routine or incident exposure." Kerr-McGee would even try to claim that Silkwood intentionally contaminated herself, but "that seems unlikely," especially since Silkwood seemed to be the most concerned and aware of its dangers.

Karen Silkwood's death

After returning to Oklahoma City on November 12, 1974, Karen Silkwood and her roommate Sherri Ellis went back to work, but they were kept from doing any tasks directly involving plutonium. That night, after going to a union meeting at the Hub Café in Crescent, Silkwood started to drive back to Oklahoma City for the meeting with David Burnham, the New York Times reporter, where she was finally going to hand over all the documentation she'd been gathering since her testimony to the AEC.

But tragically, Silkwood never made it back to Oklahoma City. According to "American Dissident," 7 miles outside of Crescent, Silkwood's car was found down an embankment, having gone off the road, hit a guardrail, and plunged off the highway. State police determined that the crash was accidental, stating that Silkwood likely fell asleep while driving. Blood tests later showed that Silkwood had twice the recommended dosage for Quaaludes in her system.

But some speculate that Silkwood's death wasn't an accident. Based on the fresh dent on Silkwood's rear bumper, it's possible that Silkwood was forced off the road. According to Women Whistleblowers, Silkwood's mother insisted that "If she was so excited [about giving over the documentation], she couldn't have fallen asleep at the wheel." It's also notable that when Stephens arrived at the scene, he couldn't locate Silkwood's documents. State trooper Rick Fagan claimed he'd collected the scattered papers and put them back in the car. But at some point, they seemingly vanished.

The subsequent autopsy and analysis

After her death, with permission from Karen Silkwood's father, an autopsy was performed by a team from Los Alamos at the request of the Atomic Energy Commission and the Oklahoma State Medical Examiner. The autopsy found 4.5 nanocuries of plutonium-239 in her lungs and 3.2 nanocuries of plutonium-239 in her liver.

According to Los Alamos Science, the highest concentration was found in the contents of the gastrointestinal tract, which "demonstrated that she had ingested plutonium prior to her death." During the autopsy, it was also discovered that there was six times as much plutonium in Silkwood's lung as there was in her lymph nodes. Usually, the ratio is "about 0.1."

However, the Environmental Defense Institute notes that the Los Alamos report doesn't explain how plutonium would've been found in the liver, especially since it seems to suggest that Silkwood was primarily being contaminated in her home. "The Los Alamos article leaves many questions unanswered as it seems to downplay Silkwood's overall ingestion and inhalation plutonium intake and whole-body dose."

Silkwood vs. Kerr-McGee

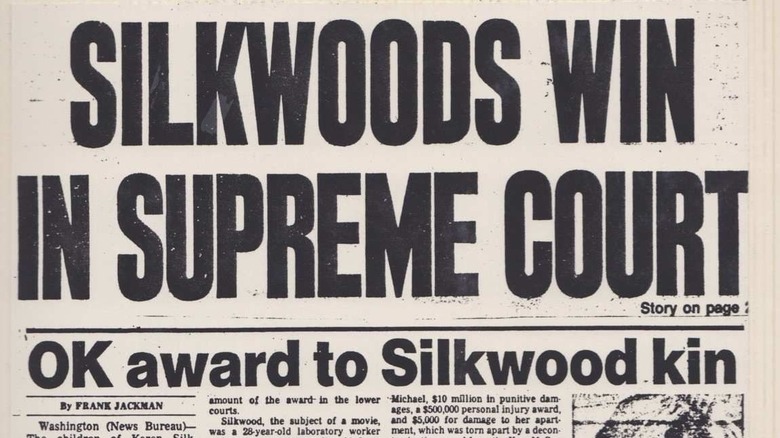

Karen Silkwood's family filed a civil suit against Kerr-McGee, seeking $11.5 million in damages and alleging that Kerr-McGee's poor safety programs led to Silkwood's contamination. Against this, Kerr-McGee tried to claim that Silkwood contaminated herself in an effort to embarrass the company. In what was the longest civil trial in Oklahoma history with the largest award for punitive damages ever, according to Women Whistleblowers, the jury decided to award the Silkwood estate $10.5 million in 1979. Although this was reversed by the Federal Court of Appeals in Denver, the Supreme Court restored the first verdict. Instead of a retrial, the suit was settled for $1.38 million in 1986.

In February 1975, Anthony Mazzocchi, who'd been working with Silkwood, suffered a strangely similar incident where he blacked out at the wheel of his car, causing it to roll over. However, Mazzocchi lived to tell the tale, going on to say, "If they knocked me out, the union would have shut up about Silkwood. There was a lot of pressure in the union to get off it. If I had died, it would have been over with," per History of Yesterday.

Meanwhile, after numerous violations of safety regulations, Kerr-McGee closed its nuclear fuel plant in December 1975. Kerr-McGee would spend over 25 years decontaminating Crescent City and as of 2019, the groundwater under the closed plant is still contaminated.