The Beast Of Bastille: The Truth About The Serial Killer

True crime dramas and documentaries might have a reputation of being sensationalistic, but here's the thing: at the heart of them all are true stories. There are victims and grieving families who had their lives changed forever during these brutal, bloody episodes of history, and Netflix's 2021 series "The Women and the Murderer" is no different. It's the story of a serial killer that stalked the streets of Paris in the 1990s, and he was dubbed "The Beast of Bastille" after the area around the infamous prison where he preferred to hunt. And hunt he did.

In between prison sentences for other offenses, Guy Georges killed, and killed, and killed again. His spree went on for years before he was finally connected to the brutal murders of seven women. He confessed when he was arrested, and even more telling was the fact that once he was behind bars for good, the deaths stopped. Here's what he did, how long it took to catch him, and why he managed to evade capture for so long.

The murders credited to the Beast of Bastille

All too often, it's the name of the killer that's remembered, and the victims that are forgotten. So, let's start with the victims. According to FranceInfo, the first was 19-year-old Pascale Escarfail, who was discovered in her apartment on January 26, 1991. No traces of her murderer were left behind.

The killer didn't strike again until January 9, 1994. Catherine Rocher was killed in an underground car park, and the location of her murder would become incredibly important to the story. Next was the November death of Elsa Benady — who was also killed in a parking lot. Then, Agnes Nijkam was killed in her own apartment on December 10, 1994. The murder was similar to Escarfail's, and law enforcement also found traces of DNA, so they began connecting the dots. The following year, Helene Frinking was killed in her apartment alongside a bloody footprint and another DNA sample.

The killer went silent until September 23, 1997. That's when 19-year-old Magali Sirotti was killed in her home, and with a now-familiar M.O. — including a sexual assault and clothing cut with a knife — law enforcement knew they were dealing with the same killer. He struck one more time and killed Estelle Magd just a month later. The killing ended with the arrest and confession of Guy Georges. Upon his arrest, it also became clear why there was such a gap in the killings: he was in prison on other charges during those quiet times.

The heartbreaking childhood of Guy Georges

When psychologists interviewed the man behind the serial killer moniker "The Beast of Bastille," they found that his urge to kill went back a long time. According to Dr. Henri Grynzspan, the heart of his problem was something called "genealogical death." In particular, Georges was the son of a woman named Helene and an American air force cook named George Cartwright. Cartwright headed back to the United States and left Helene and Guy behind. And then, when Guy was 6 years old, Helene left him, too. She went off to California to marry a different serviceman, and as if the abandonment wasn't traumatic enough, she decided to take her other son, Stephane, with her.

Does it get worse? Yes. Helene's parents were behind her decision, and while she was in the process of moving to the U.S., they welcomed Stephane into their home while sending Guy to foster care. Why was there such a difference in the way the boys were treated? According to The Guardian, it was for no other reason than Stephane was white, and Guy had a black father. Ultimately, he was bounced around through the system and the identity of his father was hidden.

Georges ended up with a foster mother named Jeanne Morin, and it's been suggested that this time he was chosen for his skin color. She previously had a black foster child that authorities had taken away, and Georges was her replacement. He later said during his confession that he loved her.

A young life filled with violent crime

The killings that haunted Paris during the 1990s paused when Guy Georges was in jail on other charges. And it wasn't his first run-in with law enforcement — they started when he was young. According to The Guardian, he hadn't yet hit his teenage years when he started stealing, and it wasn't long before that escalated into more serious crimes. The first time he got his hands on a knife he realized he could kill animals, and his later writings revealed an admiration for the tiger — especially after he allegedly crawled in a cage with one, and she seemed to recognize him as one of her own.

Georges' childhood rap sheet is a long one that includes attacks on two of the other foster children he was living with. That got him plucked from foster care and sent to a state-run orphanage, and when he was 17, he was arrested for cutting a woman's face during a mugging. Dr. Henri Grynzspan's team of psychiatrists later reported: "It is among these subjects of a genealogical death that we most often meet children who transgress laws in a violent and aggressive fashion. ... the real pleasure came from the hunt, the excitement, the wait of a man on his guard." At the end of their evaluation, they ruled that Georges was completely and thoroughly in control of his actions and knew what he was doing when he raped and killed.

The Beast of Bastille's life on the streets

In the 18 years between his first jail sentence and his arrest for murder, Guy Georges spent a good part of the time in prison. The rest he lived on the streets. Not only did the people there know him, but they spoke pretty highly of him. Philippe Dusanter was one of the hospital psychiatrists who regularly spoke with Georges and described him as perpetuating the image of an ultra-cool, small-time thief who committed the sort of crimes that didn't really hurt anyone. "He was helpful, coherent, polite, and easy-going, ready to arbitrate in disputes," Dusanter explained to The Guardian. "No one suspected him of sexual assault."

Georges — who preferred the street name "Joe" in a tribute to fictional character Tom Sawyer — traveled with the rough-living community of Paris for years and explained away his absences by saying he'd gone to another city. Trips to London and Amsterdam were used to cover up his jail time, and when he was in Paris, he always carried drumsticks and spouted hatred at the mention of the LBTGQ+ community.

Protests over police priorities

The stories of the family members and survivors are heartbreaking. The Guardian says some even organized into a vigilante group, while one father turned to the bottle and ultimately died in a car accident. The mother of the final victim, Magali Sirroti, was haunted by the fact that the final voicemail she left her daughter — "There's no need to call me back, it's nothing important" — played alongside her child's already-dead body.

Ann Gautier is the mother of Georges' fifth victim, Helene Frinking. She has been a vocal critic of the police working on the case, saying that they told her they didn't believe the deaths were the work of one man at all. Serial killers, they claimed, "were an Anglo-Saxon thing." It took a year for Frinking's neighbors to be interviewed, and when one woman escaped from The Beast of Bastille, it was 28 months before the police did a sketch of the man who tried to kill her.

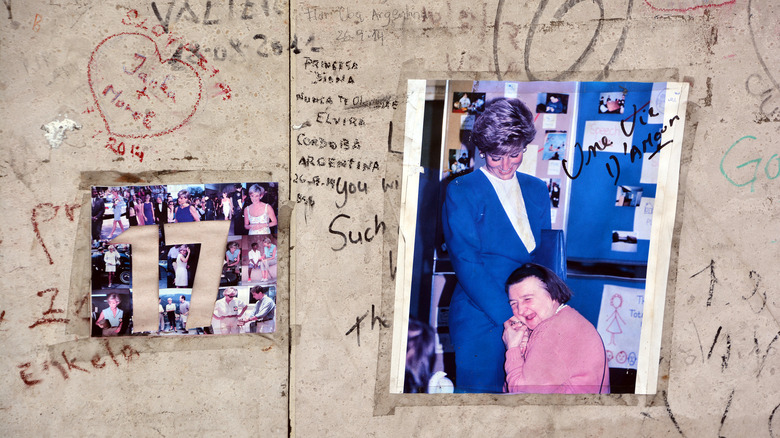

Even London's Sunday Mirror ran a piece in 1998 that pulled no punches, per The Free Library. In particular, the piece speaks to Sirroti's mother, who condemned police for spending their time, energy, and resources investigating Princess Diana's car crash, which captured headlines and priorities. "If only the police spent as much time trying to find my daughter's murderer as investigating that crash," she said. "Poor Diana's death was a tragedy, but she didn't suffer the horrendous death of my daughter or the other victims. So many lives have been wasted and so many families destroyed."

Misleading evidence and missed connections derailed the investigation

Although Princess Diana's tragic death largely overshadowed the latter part of the investigation, law enforcement was set back from the beginning. For starters, the killings were split into three separate probes when they weren't connected as having the same killer, FranceInfo reports. The murders that took place in the parking lots were considered separate from those who had been killed in their apartments until after the fourth murder, and there were other problems, too.

At the time, there was no national database even for things like fingerprints, making it impossible to connect evidence found at the crime scenes with Guy Georges — who had been on law enforcement's radar (and in jail) for a long time already. DNA was discovered on the body of the fourth victim in 1994, but again, there was no match made to the man who was already known to police.

Then, in 1995, Elisabeth Ortega was attacked in her own apartment by The Beast of Bastille. She was able to escape out a window and flee to safety, but it was a full 28 months before police took her statement for a sketch, The Guardian reports. When they did, she identified him as a 25-year-old man "of North African type." It sent police looking for a North African man when the killer wasn't that at all. Others were attacked and also escaped, and other descriptions and sketches — which were more accurate — were pushed aside.

Good cop, bad cop

In between the killing and the prison time, Guy Georges was involved in some shockingly shady stuff. In 2014, Yan Morvan wrote a piece for Vice that detailed how Georges was hired by a magazine called Paris Match to do an up-close-and-personal piece on the rougher side of France. He was put in touch with a man named Mehdi (not his real name), and when Mehdi's bodyguard — who doubled as Morvan's assistant — was arrested for murder, he was replaced by a man who was lingering on the outskirts: Guy Georges.

When the presidential elections didn't go quite the way Mehdi wanted, they were sent on another piece of investigative journalism. When Morvan was informed that if they didn't find what they were looking for, they would just make it up, he tried to quit. What followed were weeks of hell: Mehdi, with Georges at his side, informed the journalist, "You are going to work for us. You are going to do what we will tell you; otherwise, we are going to rape your wife and spray your kids with acid."

Georges became his photo assistant, and Morvan says he "was quite nice to me." That didn't make it much easier, though, and he eventually was able to escape the arrangement. With documentation of physical abuse and taped conversations of threats against his family, French police arrested Mehdi. It was another four years before he realized that he had been working alongside The Beast of Bastille, too.

A missing link ... connected with DNA

Hindsight, they say, is 20/20. And according to The Guardian, the arrest of Guy Georges came with the realization that two to three of the deaths could have been prevented had law enforcement not missed a glaring bit of information. Between Pascale Escarfail's 1991 murder and Estelle Magd's 1997 murder, Georges was behind bars on other charges — including the attempted rape of Melanie Bakou. In 1995, she was attacked outside of her apartment, but the attack was interrupted by her boyfriend, and her attacker fled. But the assailant dropped his wallet, and Georges was arrested and sentenced to 30 months. Indeed, Bakou narrowly avoided becoming a victim of The Beast of Bastille.

Georges was questioned but wasn't connected to the murders — one of which happened while he was on a day release from prison, BBC reported. Eventually, he was dropped from the suspect list before his DNA was compared to the samples taken from the crime scenes. Flash forward to 1998 when Magistrate Gilbert Thiel ordered an across-the-board comparison of law enforcement's DNA records to the sample from the crime scenes, and on March 24, 1998, they got a hit, per FranceInfo. As reported by Nature, they had the matching DNA sample since 1995, and the oversight prompted a major push to change legislation and create a national database of the DNA of convicted felons.

The Beast of Bastille's confession

Law enforcement arrested Guy Georges in March of 1998, and he went back and forth on the confessions. At first, he fully admitted his guilt, per BBC. But then he claimed he'd been beaten into confessing and withdrew it. And when it came time to go to trial, he started out with a not-guilty plea.

The trial was set to be a long one. In addition to the DNA evidence, there were 50 witnesses ready and waiting to give evidence of Georges' guilt. It was just a week into the trial when it became clear just how it was going to go, and the killer's lawyer convinced him that his best option was to admit guilt. As reported by the BBC, he ultimately admitted to all seven murders while on the stand, saying, "I ask forgiveness from my family, from my little sister, from my father, and from God, if there is one. I ask forgiveness from myself."

The sentence ... and the threat

On April 5, 2001, the BBC reported that The Beast of Bastille had been handed his sentence — and there was a good chance it would last for the rest of his life. The sentence, they said, was a minimum jail term of 22 years. Surprisingly, that's the most French law allows a person to be sentenced for, but he won't necessarily be released at the end of those 22 years. If evaluation deems he's still a threat, he'll remain in prison — and that's exactly what key witnesses recommended.

When it came time for the team of psychiatrists who had evaluated Georges to weigh in, it was their suggestion that he receive life in prison. They presented the courts with their diagnosis: Georges, they said, was a narcissistic psychopath, and if he were to be released, he would absolutely, without a doubt, kill again.

Georges spoke before the verdict and the sentence was handed out, leading the courts to believe that he had plans to commit suicide. He said: "The sentence that you are going to impose on me is nothing, I will inflict a sentence upon myself ... Life is life. You can rest assured, I will never leave prison. But I can tell you that I won't serve this sentence."

As of 2021, Guy Georges was one of the 196 prisoners behind bars at the Maison Centrale Ensisheim.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

What, exactly, is a narcissistic psychopath?

A diagnosis of "narcissistic psychopath" was presented at the sentencing — what, exactly, does that mean? What's going on here is twofold. According to the Mayo Clinic, narcissistic personality disorder is defined as an inflated sense of self-worth, superiority, arrogance, and ego that masks an underlying personality that can't handle things like criticism and even perceived slights. But Psychiatric Times says there's a bit of a misconception when it comes to the second part of that equation: the psychopath.

Psychopaths, they say, aren't completely devoid of emotion as it's often said. Instead, they suffer from an unsatisfied need to be cared for — a need that often remains unfulfilled because they typically lack self-control, are impulsive, can't return the love they want to feel, and harbor a secret feeling of inferiority, hidden beneath grandiosity, arrogance, and self-importance. It can be a deadly combination, and experts testified that for Georges, killing was a "natural impulse," and it wasn't something that could ever be rehabilitated out of him.

Carlos the Jackal and the 'I'm being framed' defense

The capture and sentencing of Guy Georges isn't quite the end of the story, though. According to The Guardian, Georges told the psychiatric team evaluating him: "Better I am in prison: outside, I am dangerous." But in the meantime, two things happened, starting with the discovery of the name of his father and the fact that he's American. Francois Honnorat was Georges' first defense attorney, who was eventually fired. He explained: "When he was finally told his father's name, it was as if he had been reborn ... Before he heard the news, he was ready to admit his crimes ... Now, he wants to take on the whole system."

Georges also grew friendly with Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, who's also known as "Carlos the Jackal." Carlos has taken the close proximity of their cells to lean hard into convincing Georges to hold the French government accountable for all the ways they've wronged him — including not getting him the treatment he so clearly needed. To that end, they've come up with a new defense, and Georges now claims he was set up after stealing a limousine. According to the killer, there were top secret documents contained within the vehicle that the French government doesn't want anyone else to see. In spite of his insistence that he's going to plead not guilty and be released — all to impress the father he never knew — his legal team says that's just not going to happen.