The Tragic True Story Of Rube Waddell

In the early years of the major leagues, the most remarkable player in baseball was not Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Walter Johnson, or Cy Young. It was southpaw pitcher Rube Waddell. Even in a decade dominated by big men with big talent, Waddell, with his searing fastball and sneaky curveball, was an all-star standout.

According to the Baseball Hall of Fame website, in 1903 and 1904, Waddell struck out more than 300 batters two years in a row, a feat not repeated until Sandy Koufax's 1965 and 1966 seasons. In 1905, he won the American League's Triple Crown, racking up 27 wins, 287 strikeouts, and a 1.48 Earned Run Average (ERA). His lifetime ERA, according to Baseball Reference, was 2.16, 11th on the major league's all-time leaderboard.

Along with his athletic skills, Waddell's on-the-field antics and his boyish, flamboyant personality attracted fans everywhere. Often considered baseball's first celebrity, Waddell did more to promote the young sport than any player before him.

Despite these triumphs, including his posthumous election to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Waddell's story has been largely lost to history. While Cobb, Johnson, Wagner, and Young live on in baseball lore, Waddell remains a ghost. That his name and legacy have been all but forgotten is a tragic testament to a life and career marred and cut short by personal misfortune, alcoholism, and other mental illness.

Rube Waddell was born under a bad sign

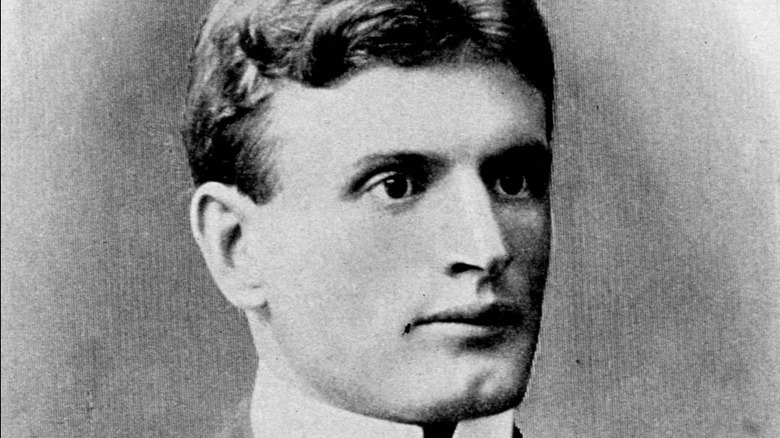

You could say George Edward "Rube" Waddell was born unlucky, as his birth day was Friday, October 13, 1876. The Pennsylvania native's raw athletic talent and super strength manifested themselves early, but so did his odd behaviors and self-destructive obsessions.

Although carefree, young Waddell was a stranger to both moderation and self-reflection, always going at full speed. According to Alan H. Levy in "Rube Waddell: The Zany, Brilliant Life of a Strikeout Artist," Waddell had his first brush with disaster when he was only 3. Drawn to the local firehouse, he wandered there from home, and several days passed before his frantic parents found him. His childish fixation with firefighting would get him into trouble throughout his life.

His baseball skills also developed early, but his throws were so fierce, the other kids feared competing against him. He rarely attended school and struggled to maintain focus.

While still a teen, he signed with a semi-pro team but was let go after one season because of frequent absences and inconsistent pitching. The Society for American Baseball Research notes that Waddell blew a second chance, when, after signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1897, he shocked the manager with his unfiltered chatter during a team meal. He was fired before he had pitched a single game.

He was a rolling stone, with many places to call his home

Between 1897 and 1913, Rube Waddell played for over a dozen baseball teams, major and minor. His career was notable not only for how many franchises he pitched for, but for how often he hopped back and forth from the majors to the minors.

Waddell's trips to the minors were due not to injuries or slumps, but to contract disputes and disruptive behavior. He would delay games to play marbles with kids or completely miss a game to go fishing. According to Robert Peyton Wiggins' "The Deacon and the Schoolmaster: Phillippe and Leever, Pittsburgh's Great Turn-of-the-Century Pitchers," during his stint as a Pirate, Waddell's flakiness not only incensed the manager, it also destroyed his teammates' confidence in him. One Pittsburgh catcher refused to play with him.

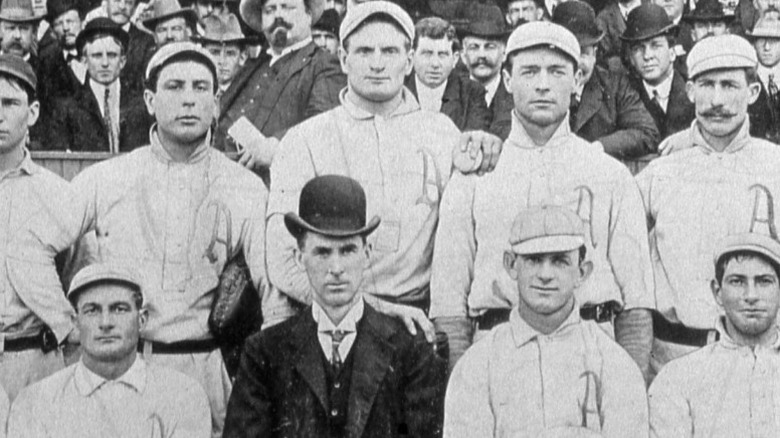

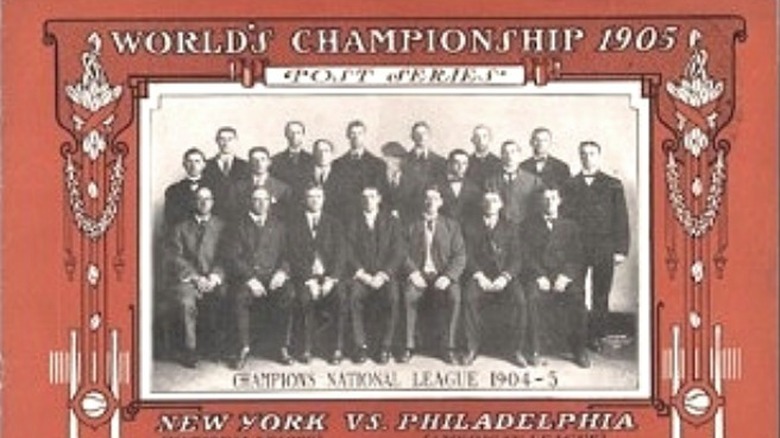

Because legendary manager Connie Mack tolerated him more than most, Waddell stayed with the Philadelphia Athletics for six straight seasons. At the top of his game, Waddell repaid Mack's loyalty by pitching the Athletics to the World Series in 1905.

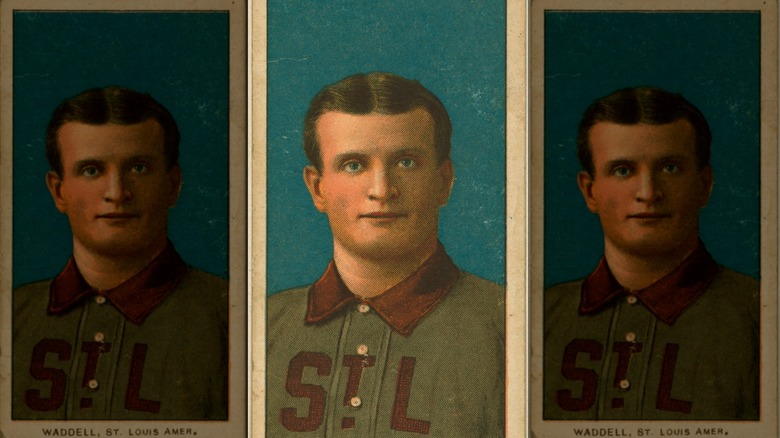

However, even Mack had his limits, and after a series of incidents, he traded Waddell to St. Louis before the 1908 season, notes the Baseball Library. As quoted in The Society for American Baseball Research, Mack explained that while he still considered Waddell a great pitcher, there "was not the best of feeling between Waddell and several of the players." Harmony being key to a team's success, Waddell had to go.

He drank fast and was paid slow

Rube Waddell's constant moving led to many contracts but very few raises. Even while his popularity with fans had greatly increased ticket sales, and soap and cigars were being named after him, he earned little money and saved none. His top reported pay, according to Baseball Library, was a meager $2,800.

Manager Connie Mack claimed that Waddell preferred winning games to earning money, but regardless of how he felt about money, Waddell spent whatever he did earn as fast as he could, and he almost always spent it on alcohol.

As noted in Philly Sports History, Mack tried different tactics to curtail his star's drinking, including doling his salary out in $1 increments. He also entrusted Waddell's travel per diem to team trainer Frank Newhouse. According to The Society for American Baseball Research, Mack instructed Newhouse to accompany Waddell everywhere and do what he could to control his spending on drink.

Often, however, Waddell outsmarted his handlers. Sometimes he would devise money-making ruses, then use the cash to buy alcohol. He would go on benders, missing games, and returning to the clubhouse in bad shape. This cycle of abuse repeated itself season after season, and with each new trade, Waddell's value as a player decreased. At one point, according to The New York Times, Waddell was so in arrears on his debts, he spent time in jail. By the end of his life, he was penniless.

Rube Waddell suffered from a robust but random love life

In his short life, Rube Waddell married three times. As noted by the Society of American Baseball Research, he first married Florence Dunning in 1899. By 1901, Dunning had filed for divorce on grounds of "gross neglect of duty."

According to Scott Simkus in "Outsider Baseball," he married his second wife, May Wynne Skinner, in 1903, three days after meeting her. They lived together only for a short time before Waddell effectively abandoned her. Over the next several years, she fought for a share of his salary and sued him in divorce court in 1908. He filed for divorce from her in 1909, according to The New York Times.

In 1908, The Scranton Republican published a classified ad on behalf of Waddell — a prospective husband looking for an "unkissed" bride-to-be. Although described as "docile and affectionate" when "not under the influence of sinister forces," Waddell was hardly a docile mate, and at the time, he was still married to Skinner.

In April 1910, as announced in The New York Times, Waddell married for the third time. The marriage to Madge McGuire and divorce from Skinner were so close together, accusations of bigamy began, as noted in The Oleans Times Herald. Later in 1910, The Spokane Press reported that McGuire had filed for divorce. Although Waddell had pledged to stay sober, McGuire cited his violent drunkenness as a cause for their split. That divorce was finalized in 1912, according to The Washington Times.

He lost his best friend to drink

For several seasons in Philadelphia, Osee "Schreck" Schrecongost was Rube Waddell's devoted catcher and his roommate. As noted by Sporting Life (via The Society for American Baseball Research), Schrecongost's "most notable trait was that he was the only catcher who could make Waddell pitch his best."

Schrecongost was almost as wild as Waddell, and their mutual fondness for alcohol made them particularly compatible. Even their public spats had a genial quality. In "My Thirty Years in Baseball," manager John J. McGraw recalled how Schreck demanded a clause in his contract forbidding Waddell from eating crackers in their shared double bed: "I didn't mind the flat crackers so much. But for a whole week last year I woke up with elephants' tusks and cowhorns stickin' 'tween my ribs."

Unfortunately, as with Waddell, Schreck's alcoholism affected his performance and enraged Philadelphia manager Connie Mack. Schreck remained a season with the Athletics after Waddell's 1908 trade, but his poor alcohol-impaired play eventually compelled Mack to release him as well.

After 1907, Waddell and Schreck never again played together, and both men's careers went into decline. Waddell had lost not only his most patient and skilled catcher but his closest friend as well. Schreck died a mere three months after Waddell in 1914. He was quoted on his deathbed saying, "The Rube is gone and I am all in. I might as well join him."

No job was too small, or weird, for Rube Waddell

As noted by Philly Sports History, when he wasn't pitching, Rube Waddell held a number of odd jobs, including bartender, semi-pro football player, alligator wrestler, and parade baton twirler. Some he did during the off-season, but many he worked before, after, and even during games. Baseball historians, according to Bleacher Report, speculate that Waddell suffered from ADHD or a similar cognitive disorder, a theory supported by his frenetic employment record.

Waddell's most publicized odd job was as a volunteer firefighter. Some sources claim he was so obsessed with firefighting he wore red underwear under his uniform so he could race after fire trucks at a moment's notice. Others insist he limited his firefighting to his off-hours but might pose as a former fireman to ingratiate himself with a local crew. Scott Simkus in "Outsider Baseball" describes Waddell fighting a terrible morning blaze with a Washington, D.C. crew, then pitching a game at the D.C. stadium the next afternoon.

Many of these jobs were dangerous and posed risks for Waddell. Even minor injuries could, and did, negatively impact his pitching. The side jobs also interfered with his training and conditioning, a major bone of contention for Connie Mack. Waddell's inability to stay in shape, mentally and physically, was yet another cause for suspensions and trades that the star-crossed pitcher could ill-afford.

Rube Waddell never walked away from a fight

No one was quicker to throw a punch or wade into a melee than Rube Waddell. His record of fisticuffs was the stuff of legends. His fights led to brief stints in jail and sometimes to suspensions and fines.

Two confirmed altercations had serious consequences for Waddell. As reported in Baseball History Daily, during a 1903 game in Philadelphia, Waddell, after enduring several innings of heckling, waded into the stands and attacked a spectator. Although the fan, a known "ticket speculator," was himself arrested, the American League president suspended Waddell for five days.

The second fight took place in February 1905 and involved both of his in-laws, with whom he was living in Boston, separate from his then-wife May Wynne Skinner. According to The Society for American Baseball Research, a drunken Waddell was preparing to move out when his father-in-law asked for board money. Enraged at the request, Waddell attacked his father-in-law with a flat iron, and when his mother-in-law tried to intervene, he hit her with a chair.

Waddell fled the scene, and an arrest warrant was issued. Through some probable string-pulling by Connie Mack, Waddell avoided jail, and charges were dropped. However, the special treatment Waddell received fueled his teammates' growing resentment of him, and the resulting bad press further stained his reputation.

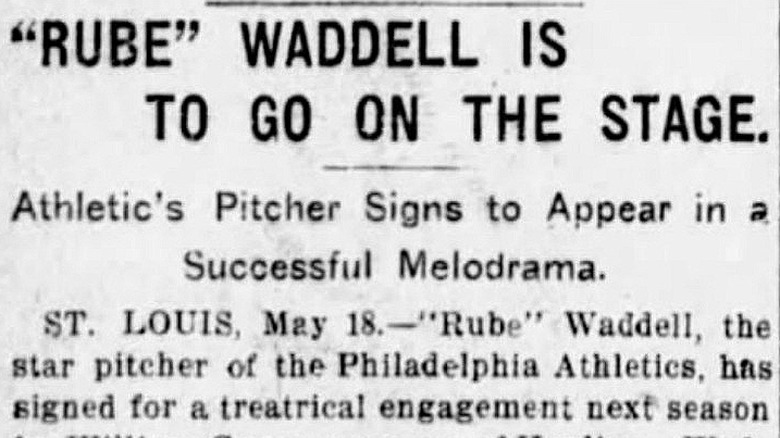

He trod ... and broke ... the boards

Because of his popularity on the mound, Rube Waddell was hired to appear in a 1903 touring stage show called "The Stain of Guilt." According to the local press (via Baseball History Daily), when the curtain came up in cities around the Midwest, Waddell was frequently "numbered with the missing." Although his role as a detective was small, he would improvise or drop so many of his lines that a Chicago reviewer commented that in "four acts of the play he delivers himself of twenty-four words."

Newspaper accounts (via Baseball Obscura) about one of Waddell's missed performances in Chicago, which resulted in an injury, were suspiciously different. In one version of the story, Waddell sneaked into a neighboring show featuring lions and was bitten by one of the stars. In another report, Waddell missed the performance after brawling with muggers.

Overall, his performance received terrible reviews, and the company fired him over a pay dispute, according to Society of American Baseball Research. Despite the pans and dismissal, rumors circulated that he would be returning to the stage in "A Daring Woman." In reaction, one critic remarked that his reappearance would be more "alarming than the news of the probabilities of war between Russia and Japan." Although rehearsals for the 1904 show apparently took place, the show never opened, and Waddell's career in show business died on the vine.

Rube Waddell lost his nerve

For much of his career, Rube Waddell indulged in goofy cockiness and pranks, on and off the field. As noted in Baseball Library, one of Waddell's favorite bits of showmanship was to send his teammates off the field during exhibition games and then strike out the side. Rules prohibited him from doing the stunt during Major League games, which required nine defensive players on the field at all times. But in one league game in Detroit, he found a way around the regulation. He ordered the outfielders to go to the edge of the grass and sit, and then he whiffed the side.

According to The Society of American Baseball Research, in another display of brashness, Waddell did cartwheels from the mound after defeating the great Cy Young in a grueling 20-inning outing. He later bartered the "winning" ball for drinks at bars around the country.

Just before the 1905 World Series, however, his signature confidence began to disappear. Although known for battling through rough patches and completing a record number of games, Waddell left a September match after two unremarkable innings. Not only was his departure from the field unusual, so was his choosing to sit quietly with fans in the bleachers instead of retreating to the dugout. It was a move that baffled the press and unnerved his coach and teammates.

The unexplained change in behavior seemed to be a harbinger of bad times to come.

The last straw was a hat ... or a bribe

Rube Waddell's life was so naturally outrageous, many apocryphal and contradictory tales sprang up about him. His absence from the 1905 World Series inspired the most infamous of them.

In one version of events, as related by the National Baseball Hall of Fame, on September 8, at the Providence train station, Waddell injured his shoulder in a fight with teammate Andy Coakley. Tradition had it that straw hats after Labor Day were a fashion no-no, and when Waddell saw Coakley wearing one, he charged him and knocked it off. During the ensuing brawl, Waddell hurt his shoulder, and a month later, the still-healing injury forced him to miss the series.

Casting doubt on the injury excuse, however, was the fact that Waddell did pitch in some games before the series. According to The Society for American Baseball Research, the more likely reason for Waddell's series absence was that gamblers had bribed him to sit it out. Betting on the World Series was big business, and the ever-broke Waddell would have been a ripe target for bribery. Suspicions against Waddell mounted, and while nothing was proven, a formal investigation was threatened.

In the end, whether he sat out the series due an injury from a silly fight or was bribed, Waddell was tried in the press, and his reputation took a big hit. In the midst of what was arguably his best season, Waddell's self-destructive tendencies had taken their most tragic toll.

In his "silent inning," Rube Waddell lost to the "white death"

As with everything else in his life, the details of Rube Waddell's final years are convoluted. After being traded to the St. Louis Browns in 1908, he continued to pitch reasonably well and draw crowds for two more seasons. However, in 1910, with his love life in tatters and his drinking and temper out of control, his career in the majors ended.

He wound up in the minors in late 1910, bouncing from team to team. According to Philly Sports History, in 1912, while he was living in Kentucky, a local dam collapsed, causing flooding throughout the region. Waddell, of course, raced to help, rescuing trapped people and standing for hours in cold water stacking sandbags at the levees.

The protracted effort, while heroic, apparently caused Waddell to contract pneumonia. In his weakened state, he also developed tuberculosis, or the "white death." As noted in his biography in The Society for American Baseball History, after struggling through most of the season, he was forced to quit pitching in November 1913. Supported financially by Connie Mack and others, the broke and weak Waddell then found care at a sanitarium in San Antonio.

Weighing a mere 130 pounds, the once strapping Waddell died a few months later, on April Fool's Day, 1914. He was only 37. In eulogy, Mack described Waddell as the greatest pitcher in the game, a kind sinner to whom he and baseball would always owe much.