Deadliest Bacteria To Ever Exist

If you go by numbers alone, there's technically more foreign and bacterial cells in the human body than actual human cells. But despite the fact that all of those bacteria are essential for our survival, that doesn't mean that all bacteria are beneficial. And while some have always been dangerous, others are getting deadlier by the day.

It's likely that humans and bacteria will always be caught in an arms race. Humans will continue to develop more antibiotic and antimicrobial therapies and bacteria will continue to develop resistances. Even if a bacterium is completely eradicated, a new one will always arise in its stead.

Before antibiotics, deaths related to bacterial infections accounted for 30% of mortality in the United States. This makes the prospect of antibiotic resistant strains especially worrisome, especially when there are few present alternatives that we have for fighting bacteria. And how do we get rid of the ones that harm us without hurting the ones that help us? But what are some of the deadliest and most dangerous bacteria that we know of? And what makes them so dangerous? Here are some of the deadliest bacteria to ever exist.

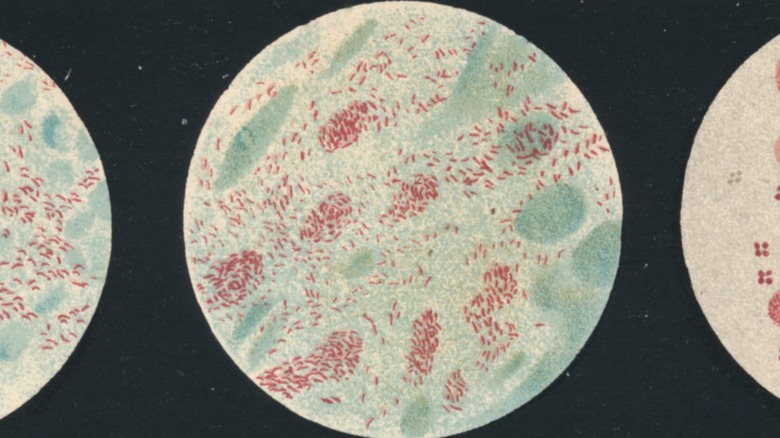

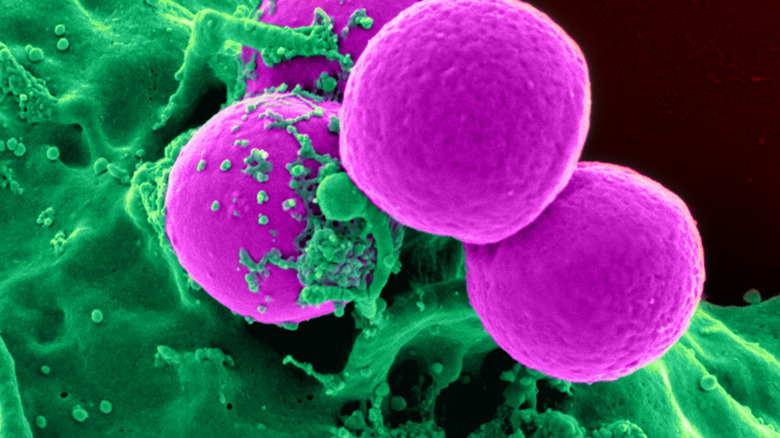

Merciless MRSA

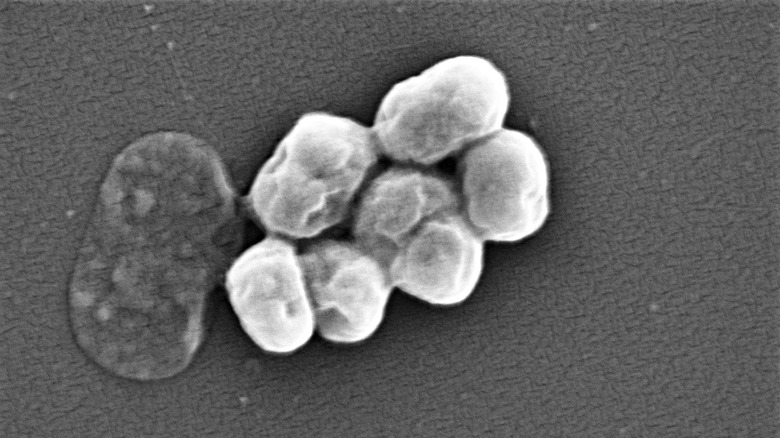

One of the most dangerous bacterial infections actually comes from a bacterium that is asymptomatically present in between 20-30% of the human population. While there are many common staphylococcal bacteria, according to the MSD Manual, Staphylococcus aureus is considered to be the most dangerous and the strain known as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, raises the stakes even higher.

First described in the 1960s, MRSA isn't too different from the typical staph infection. Staph infections can infect any part of the body, ranging from heart valves to bones, causing endocarditis and osteomyelitis. Some strains can also lead to toxic shock syndrome or scalded skin syndrome, per Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus by Paul D. Stapleton and Peter W. Taylor. But while some strains of S. aureus can be treated, other strains have developed a resistance to antibiotics, which make them incredibly difficult to treat.

Antibiotics related to penicillin are known as beta-lactam antibiotics, and when S. aureus is resistant to "almost all beta-lactam antibiotics," it's known as MRSA. When MRSA is acquired outside of a healthcare facility, it's known as a community-acquired infection, and when it's acquired within a healthcare facility, it's referred to as a hospital-acquired infection, and between them they have a mortality rate between 15% to 60%. The different kinds of MRSA have different "antibiotic susceptibility and treatment," and although incidences of hospital-acquired MRSA are decreasing in some places, like the United States, incidences of community-acquired MRSA are simultaneously increasing.

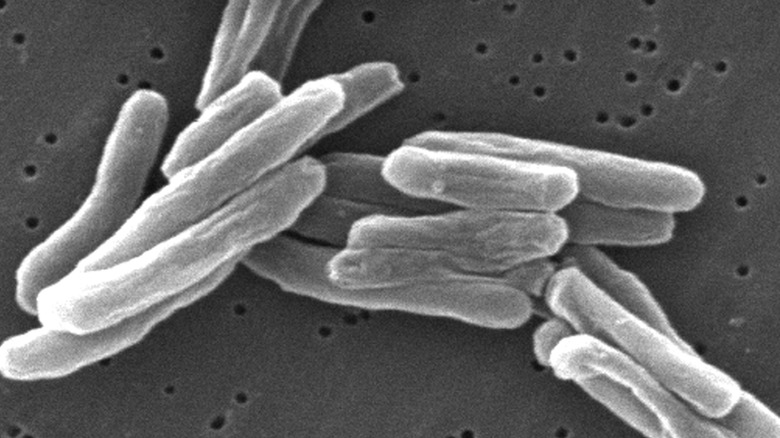

Building up resistance

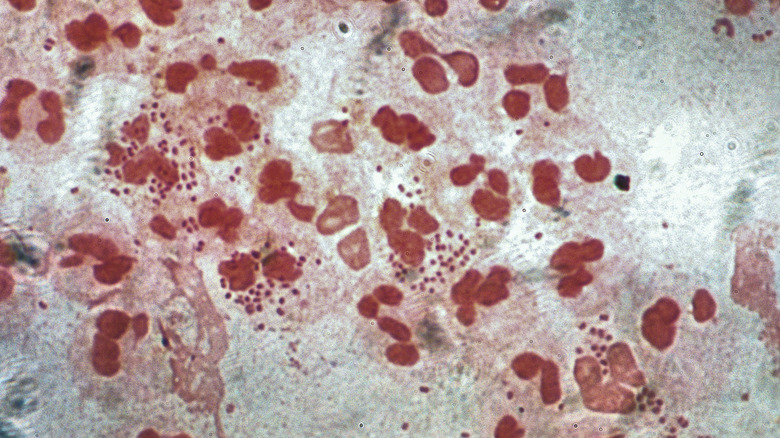

The bacterium known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been around for millions of years, and although it's not the only bacterium responsible for causing tuberculosis, it's definitely the main culprit. TB has always been associated with a high mortality rate and continues to cause up to 1.4 million deaths every year. Although TB typically targets the lungs, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can also attack the brain, spine, and kidneys as well.

According to the European Respiratory Journal, the first effective treatments for TB were discovered in 1944 and by the 1970s, TB could be cured in less than a year. Ten years later, the treatment time for TB was only six months. Streptomycin was the first antibiotic therapy to be available, and by the 1950s, some people were diagnosed with strains of M. tuberculosis that were resistant to streptomycin. As isoniazid and rifampicin started being used as the main TB drugs, strains of TB also developed with resistance to both drugs, known as Multidrug-resistant TB, or MDR-TB, writes WHO.

Extensively drug-resistant TB, also known as XDR-TB, is the rarest and deadliest form of TB, and is resistant to all main forms of treatment. Although it's not impossible to treat XDR-TB, the CDC notes that "the remaining treatment options are less effective, have more side effects, and are more expensive."

When strep becomes deadly

The bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes can cause a number of life-threatening infections, including septic arthritis, myositis, and necrotizing fasciitis. But its most common manifestation is actually the strain that causes strep throat and tonsillitis, according to Microbe. And it's believed that up to 15% of the population asymptomatically carries the bacterium.

Although there are treatments for S. pyogenes, typically penicillin, more severe S. pyogenes, known as invasive strep, may require stronger antibiotics in addition to the penicillin as well as to surgery to remove any dead tissue, per Case Reports in Infectious Diseases. Noninvasive infections include strep throat, scarlet fever, and sinusitis and in the 21st century are typically treatable.

According to Academic Forensic Pathology, it's unclear why S. pyogenes causes life-threatening infections and some but not in others, but up to 1,600 people die every year from S. pyogenes in the United States alone. Worldwide, it's estimated that every year up to 500,000 people die from S. pyogenes related illnesses. Overall, the highest mortality rates are in the first two days, but most deaths end up occurring within a week of the initial infection often through multiorgan failure.

Feeling toxic

Although known for its association with Botox, the bacterium Clostridium botulinum is responsible for more than keeping muscles in the face from contracting. C. botulinum produces the Botulinum toxin, which the Indian Journal of Dermatology refers to as "one of the most poisonous biological substances known," and can lead to Botulism in humans. And C. botulinum isn't the only bacterium that can cause botulism. The toxin that causes botulism is also produced by Clostridium butyricum and Clostridium baratii.

According to the Mayo Clinic, although botulism is rare, it's a serious condition that can arise in three forms; foodborne, wound, and infant. Depending on which type of botulism one has, symptoms can arise between 12 hours to 10 days, but all forms of botulism "can be fatal and are considered medical emergencies." The botulinum toxin affects the nervous system and results in paralysis that typically leads to respiratory failure.

HHS Public Access reports that although botulism cases in the United States were fatal in over 60% of cases before the 1950s, by the 1990s mortality rates fell to under 10%. And according to Medicine Net, because of better canning procedures, the number of cases of foodborne botulism has dropped worldwide to about 1,000 annually.

Good vs. bad

Although Escherichia coli normally lives inside the intestines, some strains can do some serious damage if they end up there. Those strains include Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, or STEC, due to the Shiga toxin that they produce, which damages the lining of the small intestine and causes diarrhea, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

STEC and other strains of E. coli are primarily contracted through contaminated water or food and since it cannot survive in higher temperatures, cooking food in temperatures of 70 °C or higher can ensure that the E. coli is destroyed. However, although it's not always fatal and the diarrhea and abdominal cramps can usually resolve within two weeks, in some people, E. coli can cause hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which is life-threatening, according to WHO.

It's estimated that worldwide, up to 200,000 people die from E. coli related infections every year out of over 300 million who contact E. coli, but infection rates also vary heavily by region. And the journal GMS Infectious Diseases writes that although E. coli related illnesses can be treated with antibiotics, STEC infections can sometimes be made worse by antimicrobial agents. Antibiotic resistance is also an issue in E. coli infections and although the incidence is not too high yet, it's still a big cause for concern since E. coli is one of the most common bacterium and can easily transfer its resistance to other strains, per the Journal of the São Paulo Institute of Tropical Medicine.

Rarely fatal or fatally rare?

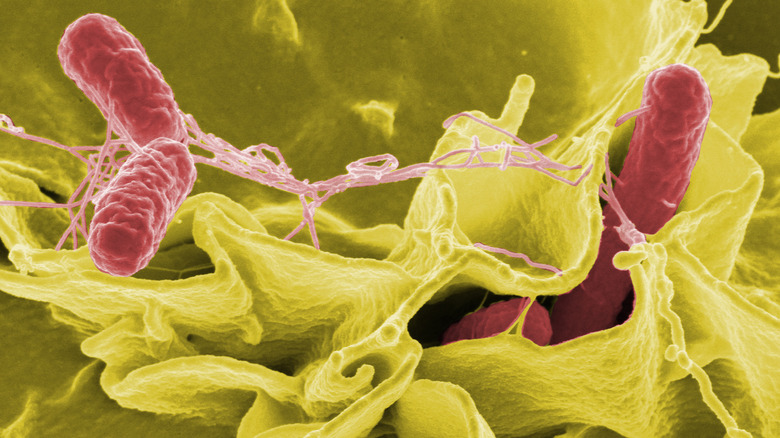

Despite the name, salmonellosis isn't usually caused by salmon, although it's definitely one of the many ways that people can contract salmonellosis, since it can be found in any contaminated food, whether it's meat or vegetables. However, the main source of salmonella infections in humans tend to come from chicken and pigs.

According to HHS Public Access, 99% of salmonellosis infections in animals are caused by the bacterium Salmonella enterica and in humans will cause either non-invasive non-typhoidal salmonellosis, invasive non-typhoidal salmonellosis (iNTS), or typhoid fever. Of the three, iNTS and typhoid fever are the deadliest illnesses caused by S. enterica. Even with treatment, iNTS can have a fatality rate of up to 47% and typhoid fever caused by Salmonella leads to almost 200,000 deaths worldwide every year.

The CDC estimates that 94% of salmonella infections occur from eating food contaminated with the feces of an infected animal, but outbreaks have also been linked to direct contact with animals as well. And while the bacteria will start off in the stomach, it can spread to the bloodstream and infect major organ systems, like the liver or bones.

Typically, salmonella is treated with antibiotics, but rehydration of fluids and electrolytes are considered to be the most important, since the diarrhea caused by the infection cause lead to dehydration.

Not that kind of super

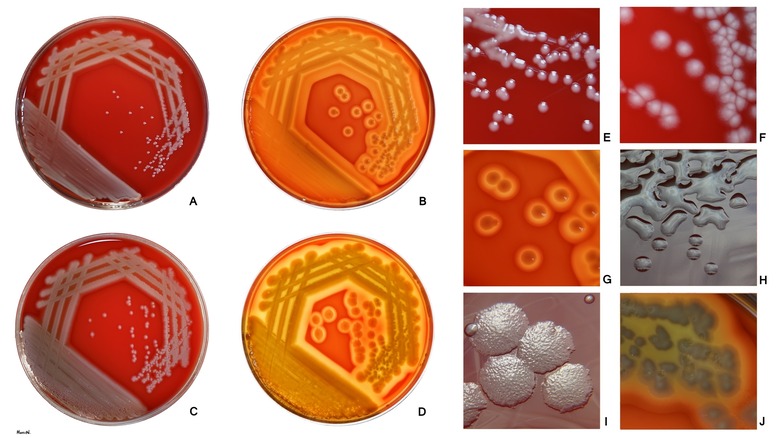

Penicillin started being used as a treatment for the STI gonorrhea in the 1940s, and by 1946 penicillin-resistant gonorrhea. Further resistances were reported in the 1970s and 1980s and despite the current successful uses of azithromycin and ceftriaxone, the next stage of gonorrhea resistance is here, and it's known as super gonorrhea. According to WHO, super gonorrhea refers to when the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae becomes a "superbug," causing "extensively drug-resistant gonorrhea with high-level resistance." And this resistance applies to penicillin, azithromycin, ceftriaxone, and several other antibiotics. As of 2018, super gonorrhea had been reported in numerous countries including Australia, France, and the United Kingdom.

Although untreated gonorrhea rarely causes death, it can lead to a number of long-term conditions and discomfort. For people with uteruses, untreated gonorrhea can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, which can cause long-term pain and infertility. And for people with testicles, it can lead to epididymitis, which causes scrotal pain and swelling. Stanford Health Care also writes that in rare cases, the bacterium can enter the bloodstream and infect other parts of the body, causing joint pain and skin sores, among other symptoms. It's at this point that gonorrhea can turn deadly.

The first instance of incurable gonorrhea was reported in 2018 and it's only a matter of time before even the best antibiotics simply aren't enough.

A troublesome pathogen

The bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii is quickly becoming one of the most dangerous pathogens humans have to confront. Although it's typically found in soil and water, it's being contracted more and more in hospital environments, though high incidences have also been reported among U.S. Army service members in Southwest and Central Asia.

According to Clinical Microbiology Reviews, A. baumannii strains have been reported that are resistant to "all known antibiotics" and can cause pneumonia, skin/soft tissue issues, urinary tract infections, and central nervous system problems. And its antibiotic resistant behavior is incredibly worrisome to scientists. The journal Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology describes A. baumannii as "one of the six most important multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms isolated in hospitalized patients worldwide."

Although global mortality rates for illnesses caused by A. baumannii vary, overall mortality for some of the illnesses it causes can be as high as 43%. The incidence of drug-resistant A. baumannii is also high, and in places like China has been reported to be 60.1%. In the United States, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter caused 700 deaths out of 8,500 infections in hospitalized patients in one year alone, per the CDC.

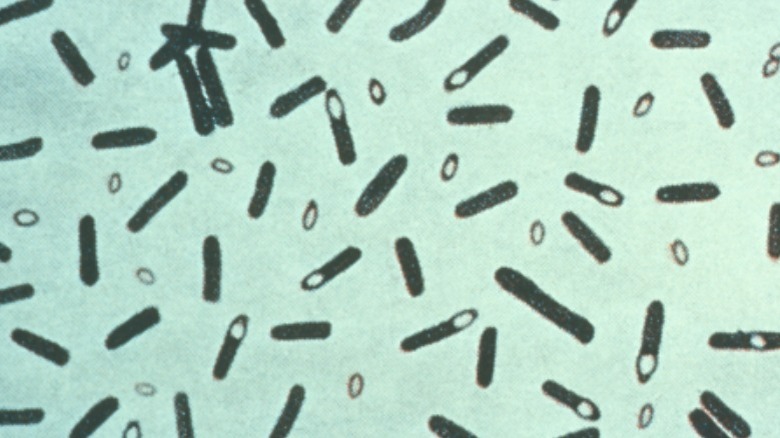

Spores galore

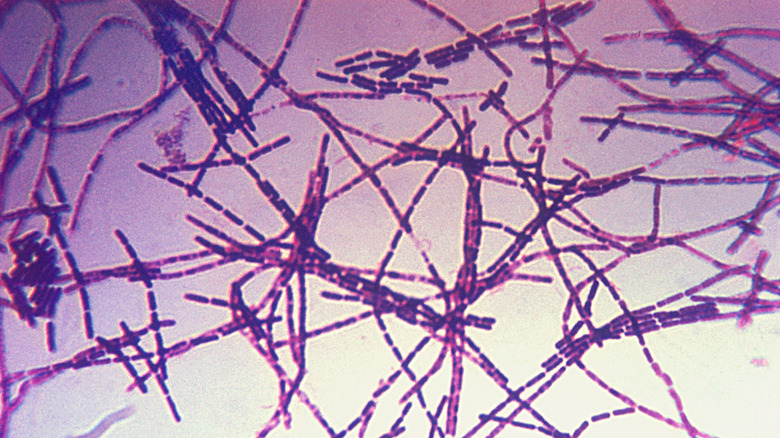

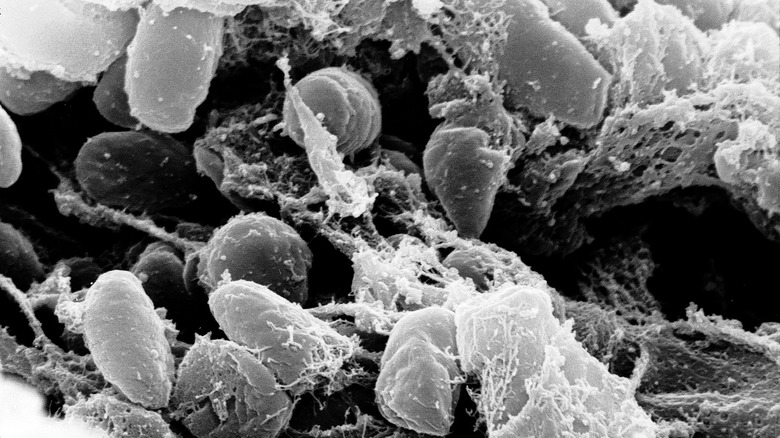

You may not instantly recognize the name Bacillus anthracis but that's because the bacterium is often overshadowed by the disease it causes: anthrax. When B. anthracis dries, it forms spores that can stay viable in animal hair or soil for years until it enters the body. Once it's inside, the spores start multiplying, causing the condition known as anthrax. According to the CDC, depending on where the anthrax enters the body, symptoms will vary, but all types of anthrax have the potential to be fatal.

But MSD Manual writes that the mortality for inhalation and meningeal anthrax is the highest, with practically 100% of cases being fatal if left untreated. But with treatment, mortality rates drop to about 50%. In comparison, cutaneous anthrax, which is the most common form of anthrax, is fatal in less than 1% of cases when treated and only 5% to 20% of untreated cases.

Historically, people have tried to use B. anthracis as a bioweapon several times. During World War II, Unit 731 of the Imperial Japanese Army experimented with both anthrax and botulism as part of their biological weapons program. And in 2001, Bruce Edwards Ivins was reportedly responsible for mailing letters filled with anthrax spores to several news media outlets and Democratic Senators. Five people died as a result and 17 others fell ill in what the FBI calls "the worst biological attack in U.S. history."

A plague on every house

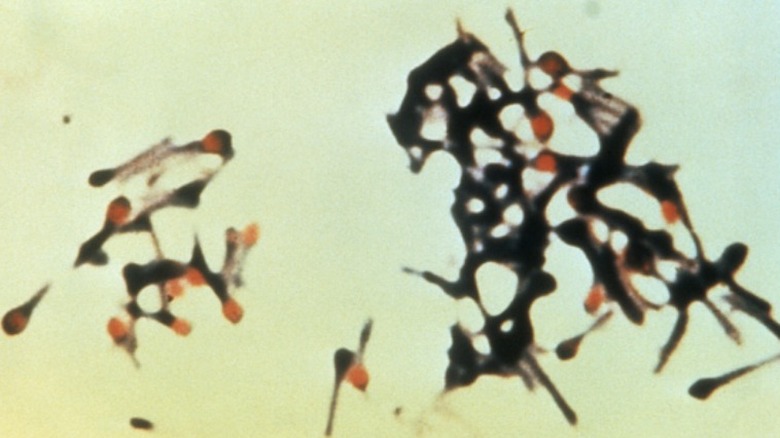

For most of recorded Western history, the bacterium Yersinia pestis has swept back and forth across Asia, Africa, and Europe. While the most well-known occurrence is the Black Death during the 14th century, Y. pestis, also known as the plague, would repeatedly reappear over the years, starting from the Justinian Plague of 541-544, according to JMVH. And the total number of deaths is unknown. During the Black Death alone, it's estimated that up to 50 million people died in Asia, Africa and Europe combined, per WHO.

Y. pestis causes three types of plague: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. And although the bubonic plague is the most well-known due to its iconic boils, or buboes, the pneumonic form is always fatal if left untreated. In comparison, bubonic plague only has a 30% fatality rate.

In the 21st century, Y. pestis is treated with a cocktail of strong antibiotics, including doxycycline and levofloxacin. But the plague hasn't been lost to history. Between 2010 to 2015, there were over 580 deaths attributed to the plague. And in 2019, after a Kazakh couple in Mongolia died from the bubonic plague, a 6-day quarantine was initiated to prevent further infections, The Guardian reports.

Resistant pneumonia

Several bacteria cause pneumonia, but one of the most serious causes continues to be the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. And pneumonia isn't the only illness that P. aeruginosa can cause. It's also responsible for urinary tract infections and in some cases can pass into the blood, especially after surgery, according to the CDC. And according to Current Microbiology, not only does P. aeruginosa intrinsically have high antibiotic resistance, but it has the ability to develop new resistances during treatment. As a result, "these infections are difficult to eradicate."

When P. aeruginosa first emerged in the 1960s, it had a mortality rate of roughly 90%. But as antipseudomonal antibiotics were developed, the mortality rate was brought down and is now between 18% to 61%, writes Clinical Infectious Diseases.

With multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDRPA) there are limited treatment options but treating even a basic Pseudomonas infection is difficult because it's "clinically indistinguishable from other forms of gram-negative bacterial infection." As a result, people are often initially given antibiotics that are ineffective against P. aeruginosa, resulting in a delay in proper treatment coupled with "inappropriate antimicrobial therapy[, which] is associated with adverse outcome[s]."

Be careful where you step

If you can't remember the last time you got a tetanus shot, it's not a bad idea to get a tetanus booster, which is recommended every 10 years. Similar to anthrax spores, the spores of bacterium Clostridium tetani can survive for years in soil and feces. But once it enters the human body through an open wound, its cells start multiplying and releasing a toxin known as tetanospasmin, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Also known as lockjaw, tetanus is characterized by muscle spasms, jaw cramping, and painful muscle stiffness. And according to Our World in Data, tetanus has been reported to be fatal in 11% of cases, with almost half of the cases being children younger than five years old. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control writes that tetanus is estimated to be responsible for between 200,000 and 300,000 deaths worldwide every year.

Due to the effectiveness of the tetanus vaccine and booster coupled with the widespread vaccination efforts, since 1990 there's been an overall "89% reduction in tetanus cases and deaths," writes Clinical Medical Reviews and Case Reports. And while many of these reductions have come in Western countries, like the United States, with the rise of anti-vaccination movements, tetanus cases are slowly coming back.

Dehydrated to death

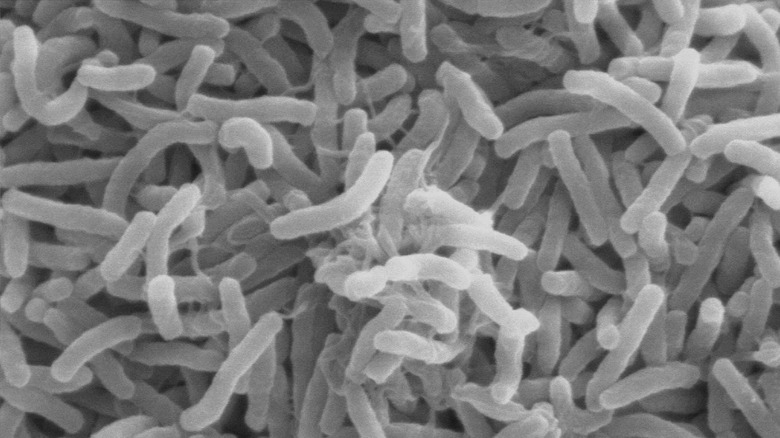

Caused by a subset of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, cholera continues to cause over 100,000 deaths worldwide annually. But according to WHO, there's a global goal to reduce cholera deaths by 90% by 2030.

In the 1990s, the subsets of V. cholerae that cause cholera were divided by scientists into O group 1 and non-O1, depending on whether they "agglutinated with serum from cholera patients." V. cholerae thrives in water and once infected, people can spread V. cholera through their feces, especially if it gets into the water system. V. cholera can also be transmitted through raw or undercooked shellfish, but such cases are relatively rare.

The Cleveland Clinic writes that cholera symptoms are generally mild, but 10% of people develop, in addition to diarrhea, muscle cramps, vomiting, and weakness. And in the end, the diarrhea and vomiting from cholera can lead to such severe dehydration that it causes kidney failure, coma, and death. Because dehydration is the immediate cause of death, cholera is often treated by replenishing fluids and salts rather than antibiotics. While antibiotics can shorten the length of the illness and help with severity, rehydration is the most important thing. And the CDC reports that if it's promptly and properly treated, less than 1% of cholera cases are fatal.