Why George Washington's Second Term Was A Nightmare

After a storied career in the military (and a childhood that has since been mythologized to emphasize the importance of telling the truth to one's parents), George Washington became the first president of the United States, taking his oath of office on April 30, 1789, at the age of 57. Although we now know that Washington's accomplishments during the American Revolution might have been inflated a bit to emphasize his greatness, he was arguably the best man for the job, and the right person to lead the young nation as its very first head of state.

All told, Washington's first term was fairly eventful, and most of it in a good way; as his first four years in office drew to a close, he was looking forward to returning to Mount Vernon, his home and plantation, and living the rest of his years quietly as a private citizen. But he did eventually opt for a second term, and it's safe to say that he might have gotten more than he bargained for during those four additional years in office. Here's why George Washington's second term as president of the United States of America was considered a nightmare.

Washington had to be persuaded to run for a second term

As he was wrapping up his first term in office, George Washington didn't seem interested in a second one. As noted by MountVernon.org, the president was disheartened by the dramatic increase in partisanship in the United States at the time — he didn't need that stress in his life, and it seemed that all he wanted to do was to retire quietly to Mount Vernon. On the other hand, he was also worried about the possibility of a nation divided, so when his advisers told him that he should serve another four years in office, he agreed.

Washington was re-elected unanimously, but as he prepared for his second term, there were signs that he wasn't 100% onboard with the idea of a second term, including the fact that he gave the shortest-ever inaugural speech ever at just 135 words, per White House History. He did, however, reaffirm his commitment in words while delivering his laconic speech. "I am again called upon by the voice of my Country to execute the functions of its Chief Magistrate," the address read in part (via Miller Center). "When the occasion proper for it shall arrive, I shall endeavour to express the high sense I entertain of this distinguished honor, and of the confidence which has been reposed in me by the people of United America."

There was serious infighting within Washington's cabinet

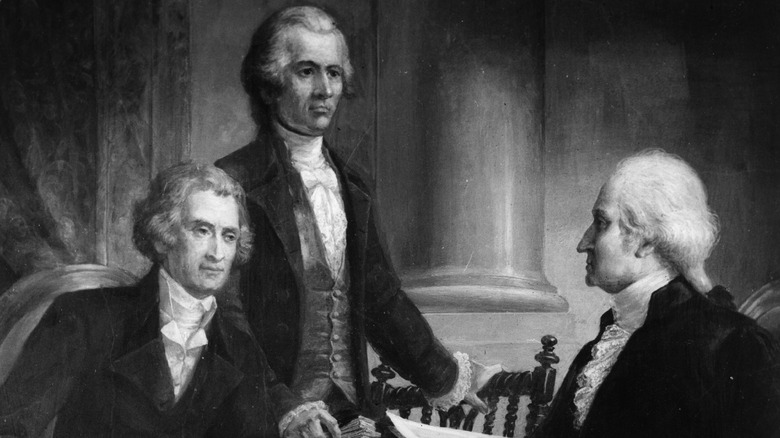

Whenever there are two people who have conflicting influences, ideologies, or what have you, it's usually a case of playing with fire for the person who hires the mismatched pair to work for them. According to MountVernon.org, that didn't faze George Washington when he asked Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton to serve in his Cabinet. In fact, there was a time when Secretary of State (and future president) Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton were on more than civil terms with each other. But with both men under the impression that they had the most important position in the Cabinet, Washington soon realized that he might have opened up a can of worms.

It didn't help that Jefferson and Hamilton had vastly different personalities that further highlighted the oil-and-water dynamic between them. The secretary of state was a non-confrontational type who kept a low profile, while the Treasury secretary was bold, overly frank, and ambitious, the extrovert to Jefferson's introvert. Due to this personality clash, Jefferson saw Hamilton as being overly aggressive, while Hamilton saw Jefferson as a person who sneakily disguised his own ambitions of power. Ideologically, the two Founding Fathers were at odds as well, with Jefferson favoring a "society of property-owning farmers who controlled their destiny" and Hamilton preferring an urbanized merchant economy (via Time). Further muddling things was how Jefferson sided with the French and Hamilton favored the British when both nations went to war in 1793 (via WhiteHouse.gov).

The divide between Hamilton and Jefferson became so great that Washington sent individual letters to each of them, imploring them to set aside their differences and work together for the good of the country.

All that neutrality business didn't sit well with Americans

The word "neutrality" often goes hand-in-hand with the word "controversy" — does anyone still remember what a hot-button issue net neutrality was back in the mid-2010s? If we are to go back to much older and simpler times, there was also quite a hubbub over another kind of neutrality during George Washington's second term.

As the French Revolution, which started in 1789, began to heat up a few years later, there was much pressure on the U.S. to help France out, effectively returning the favor after the latter country supported the former during the American Revolutionary War. Washington, however, maintained that it wasn't wise to interfere in another country's war, hence the Neutrality Proclamation on April 22, 1793. "The duty and interest of the United States require," the document read, via MountVernon.org, "that they [the United States] should with sincerity and good faith adopt and pursue a conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent Powers."

What made this proclamation nightmarish for Washington was the negative reaction he got for wanting America to stay neutral. "The cause of France is the cause of man, and neutrality is desertion," wrote one anonymous critic in a letter to the president. Then you had opposition newspaper editors, who felt that the French Revolution was a proper sequel to the American Revolution and that Washington was allowing the U.S. to betray a trusted longtime ally through his proclamation.

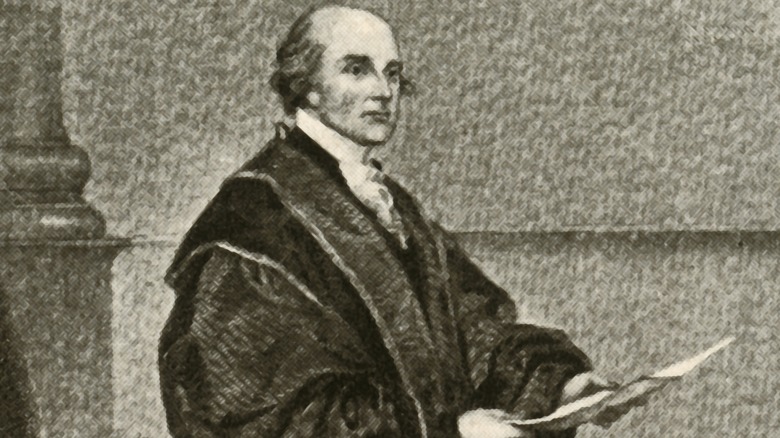

Washington dealt with the fallout from the unpopular Jay Treaty

Beyond all the infighting in George Washington's cabinet during his second term and his staunch, yet divisive push for neutrality, there was the far more serious matter of a potential conflict with England. The 1783 Treaty of Peace between the U.S. and England officially ended the Revolutionary War, and while relations between both countries were fairly tense in the decade that followed, England's conflicts with France in 1793 really sent the alarm bells ringing. Per MountVernon.org, England was allegedly violating neutral shipping rights to give it leverage over France while also refusing American ships at its ports and not following certain sections of the Treaty of Peace. This only made Washington's second term feel even more stressful than it already was, though he had a plan to ensure that the tenuous peace between the U.S. and England remained in place.

That plan involved sending Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay (pictured above) to England in an effort to prove that America has a "reluctance to hostility." On November 19, 1794, Jay signed the treaty that would eventually bear his name. At that point, though, he didn't have much bargaining power, and the agreement clearly skewed toward England in economic and military matters.

Despite negative public reactions, which included massive protests that continued well after the fact, Washington ratified the treaty in August 1795 — it wasn't the most "favorable" move for him, but it was at least better than a fluid situation in which England could declare war on the U.S. at the drop of a hat.