The History Of Snake Handling In Religion

How to practice one's religion can get to be a pretty complicated and tricky matter in just about any context. Adherents of a given faith might fret over the type of clothing they wear, the food they eat, the language they use in worship, and how they might interact with people outside of their group, for starters. They might also take time to deeply consider and debate the particulars of a holy text and how it should relate to someone's daily life. And that's not even including the rather thorny question of whether or not they should incorporate venomous reptiles into their services.

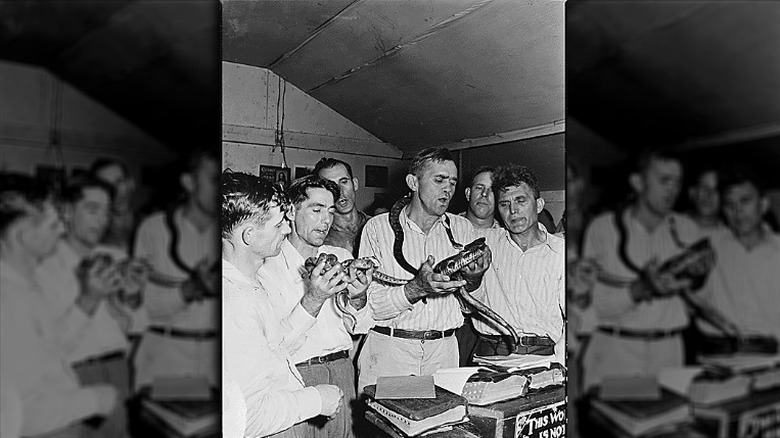

Though that last statement may seem odd in the extreme to some people, it's actually a real and long-established practice commonly known as snake handling. According to National Geographic, it's now most often understood as a uniquely American religious observance, typically practiced in rural Appalachian churches that are associated with Pentecostal Christians and other charismatic Protestant denominations. Even today, some small churches still carry on the practice alongside other signs of devotion to God, like drinking poison and speaking in unknown languages.

It's not a new practice. This form of snake handling sprung up in the early 20th century, based on a set of Bible verses that say the faithful will be able to handle serpents and drink poison, yet remain unharmed. In other religious contexts, it can go back even further. This is the oftentimes dramatic and dangerous history of snake handling in religion.

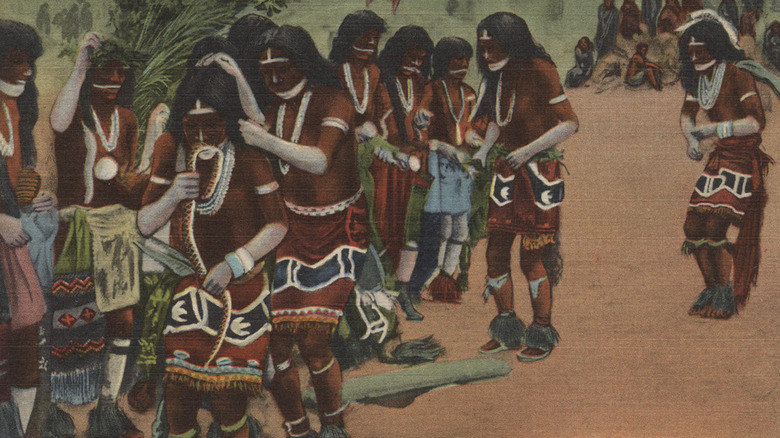

Snake handling occurs in some non-Christian contexts

Though it's now often thought of as a Christian practice, the handling of snakes does in fact show up in other religious and spiritual settings. As Encyclopedia.com reports, Mesoamerican people certainly performed ceremonies and created artwork in honor of fantastical plumed serpents. Meanwhile, practitioners of Haitian vodou can pay homage to Dambollah, who's often shown as a snake.

These sorts of beliefs have sometimes translated to documented instances of non-Christian snake handling. Amongst the Pueblo people of the American Southwest, it was an important shamanic practice. According to the Los Angeles Times, a shaman from the Yokut tribe would lead a ceremony wherein some tribal members would collect rattlesnakes (made sluggish by cool spring weather) and dance with them. Sometimes, they would encourage the snakes to bite them and, assuming the dancers survived, would be able to prove they had great power. The Chumash people had a similar dance, though they often used it to determine whether or not they wanted to eat a snake afterward.

A 1943 article in The Scientific Monthly reported yet more snake handling amongst members of the Hopi tribe, who would take up the snakes in a ritual dance and sometimes carry the reptiles hanging from their mouths. Some reportedly claimed that they would be safe so long as they were of a good, upstanding character, while others pointed to a deep understanding of snake behavior and perhaps even an unknown substance that would drug the snakes into compliance.

Christian snake handling is mostly a 20th century phenomenon

For many people, the religious practice of snake handling is deeply tied to protestant Christianity, especially as it's practiced in the rural churches of Appalachia.

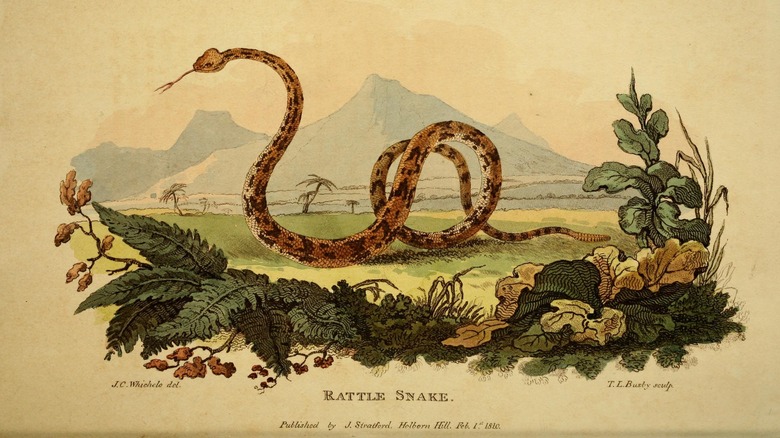

Many sources, like Encyclopedia.com, credit Tennessean George Went Hensley with introducing the practice in the early 20th century, when he first brought a rattlesnake to a church service in 1909. Hensley would get unofficial acceptance from the Church of God in 1914, though the church seems to have quickly backed away from the practice by the late 1920s. By then, however, it was too late for official or unofficial sanctions to stop snake handling, which had already taken root in numerous church congregations in the Appalachians and other parts of the American South.

However, The Mountaineer argues that he may not have been the first person from that region or religious persuasion to bring venomous snakes into a church service as a show of faith and obedience to God. Per the publication, pastor Jimmy Morrow claimed that a Virginia woman named Nancy Younger Kleiniek promoted the practice around 1890. According to Morrow's account, Kleiniek handled snakes at revival meetings throughout the region, including stops in Tennessee, both of the Carolinas, and Kentucky.

Justification for snake handling comes down to a key set of Bible verses

For many historic and modern churches that deal with snake handling, the practice all comes down to a set of Bible verses that command the faithful to take up serpents (via ABC News). At least, those lines do when read under a fairly literal interpretation of the holy book in question.

First, there's Mark 16:17-18: "They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover." Meanwhile, another gospel also seemingly encourages snake handling, as Luke 10:19 tells the faithful that "Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions" without being harmed. Some churches may also reference Acts 28:1-6, where the apostle Paul wrangles a venomous snake that, though it bites him, causes the faithful man no harm.

However, there is still plenty of debate amongst churches as to how, exactly, the passages should be taken. Some argue that a literal definition of the verses is too simplistic and that references to "serpents" can reasonably be taken as larger references to misdeeds or general evil in the world. Others might question the utility of testing God, who famously doesn't cotton to that sort of thing, given that Matthew 4:7 contains the well-known line: "Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God." For the skeptical, picking up a rattlesnake during a church service is doing just that.

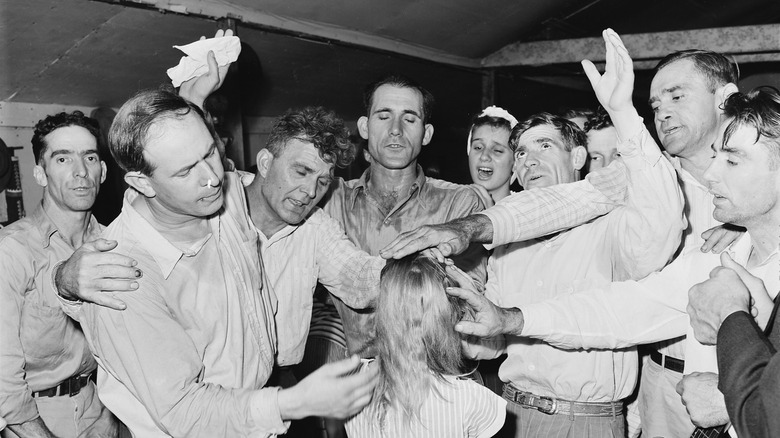

It's linked with other dramatic practices

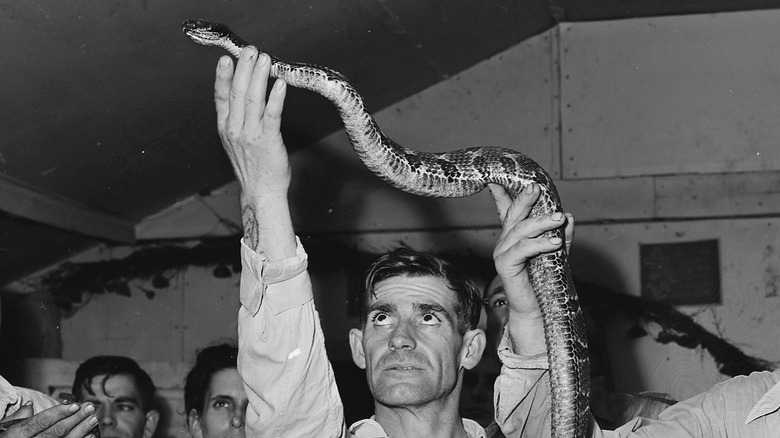

If you were to attend a snake handling service, you may be distracted by the reptiles, especially if you're not particularly fond of slithery, venomous creatures. But, if you could tear your eyes away from the ecstatic spectacle for a moment, chances are pretty good that you would notice it's accompanied by any number of boundary-pushing charismatic practices.

For instance, some churches, both in historical contexts and even today, have also made space for parishioners to drink strychnine or other deadly poisons. According to Mental Health, Religion & Culture, this practice of downing poison typically stems from a person's assertion that they needed to either combat the devil in this fashion or were moved to do so by God's command. Believers may also state that they know themselves to be protected by the Almighty. Yet, it can still be incredibly dangerous for even the most faithful, as the New York Times reported on the 1973 deaths of two churchgoers in this manner, including a preacher who had drunk strychnine.

Other practices often seen in churches that practice both snake handling and poison drinking are far less deadly, though still dramatic for many outsiders. According to Britannica, this can include glossolalia, more popularly known as "speaking in tongues." People who utter these seemingly unintelligible words and phrases do so in an ecstatic state. They may also claim that they are communicating with heavenly spirits or acting as a conduit for divine revelation.

Snake handling is a distinctly Appalachian practice

Though it's been linked to other cultures and religions, snake handling is now almost universally thought of as a product of the oftentimes remote communities of Appalachia. According to NCPedia, this practice is especially prominent in southern Appalachia. It may have arisen there due to a confluence of pre-existing religious belief, relatively isolated churches, and a certain amount of happenstance. George Went Hensley, who's often credited with introducing snake handling to protestant churches there and who clearly had a hand in popularizing it, first started it in Tennessee. Perhaps if Hensley had lived somewhere different, we'd link snake handling to intensely devoted religious communities in, say, rural Maine or the Pacific Coast.

NCPedia also notes that some midwestern churches also were known to host snake handling, in part because congregants had brought the practice with them as they moved from Appalachia. However, it's not clear if snake handling still goes on in other regions, as most of the press coverage largely focuses on Appalachia.

In 2013, NPR reported that there were an estimated 125 churches that still practiced snake handling, mostly located in a swath covering the southern portion of the Appalachian Mountains, as well as parts of Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Yet, a great majority of states outlaw the practice for what many consider to be obvious safety reasons.

Snake handling churches are often secretive

Few, if any, churches that practice the handling of serpents are eager to advertise their activities. In part, that's because there's often a serious legal challenge involved when someone brings out a deadly rattlesnake in the midst of a church service. In many states, the practice has been banned outright after numerous deaths, including a Tennessee law that was passed in 1947 after numerous churchgoers were felled by snakes in just a few short years (via ABC News). Even if it's part of a sincere devotion and generally accepted by a church's congregation, snake handling can still put someone on the wrong side of the law.

Then, there's the social component. In the early 20th century, says the Review of Religious Research, snake handling was growing in popularity. It eventually got tacit approval from a number of religious authorities, including the Church of God, a branch of Pentecostalism. Yet, that only seemed to work so long as the Church of God remained a relatively niche group. As they grew in popularity, "high-cost" practices (like dealing with potentially deadly snakes while in an ecstatic state) came under greater scrutiny. Many churches within the denomination abandoned snake handling, but some smaller groups held onto the practice despite losing the support and recognition of the larger organization. For some churchgoers in these "rebellious" congregations, it may have been easier to keep mum about it all in some wider circles.

Multiple people have been killed by snake handling

Despite a person's faith or submission to God, the bare truth is that snake handling can be deadly. Take Kentucky pastor Jamie Coots, who had previously appeared in a number of televised reports and features on snake handling, including the National Geographic special, "Snake Salvation." According to ABC News, Coots was bitten by a rattlesnake during a 2014 service. He reportedly refused medical treatment and, when an ambulance crew found him unconscious at home, his wife signed a form also declining treatment for her husband. He died later that night from the effects of snake venom.

While some took it as an affirmation of Coots' faith and submission to God's will, others were more reluctant to accept his death. Andrew Hamblin, another pastor who had been outspoken about practicing snake handling in his own church, told National Geographic that he hadn't offered it in the wake of Coots' death. "Since Jamie died, I've offered a rattler to no one. I am the shepherd, and I am responsible for what happens in this building," he said.

Hamblin, along with a growing number of other snake handling preachers, actually encourages getting medical attention as soon as someone is bitten. After all, there is no Bible verse that says you can't call 911 after a rattlesnake strikes. Even "Little Cody" Coots, the son of Jamie Coots, requested emergency medical attention after his own encounter with a rattlesnake. Unlike his father, Little Cody survived.

Snakes don't bite handlers all the time

While there are plenty of stories of pastors and other congregants who are bitten by snakes, what's more surprising are the number of people who reportedly handle venomous reptiles and manage to come away from the experience unscathed. How do they manage to handle snakes in a situation that could be potentially stressful and bite-inducing for the animal, yet walk away without a single wound?

According to National Geographic, it's possible that members of a congregation could still be cautious and gentle when handling snakes, though they may appear to be in a trance state otherwise. A relatively calm snake is less likely to bite the human carrying it around, though very few experts would recommend doing so under any conditions.

How the snakes are housed and maintained can also have a significant effect both on the likelihood of bites and just how much venom could be delivered in a single strike. Per National Geographic, a snake that's in a weakened state may not be able to pump a full dose of venom when it bites. Snake experts interviewed by NPR also noted that many snakes seem to be kept in pretty poor conditions, with dirty, crowded cages and little water or food. Pastor Jamie Coots, interviewed by the outlet prior to his 2014 death, admitted that his snakes lived only an average of three to four months in captivity, compared to a decade or more for well-managed snakes in a zoo.

Why haven't all bitten snake handlers died?

Though it's technically possible for people to handle snakes without being bitten, it's still a practice that many outside of these church services strongly discourage. That's because, seemingly regardless of someone's faith or the weakness of an individual snake, it's still possible to be bitten by an agitated and very venomous snake. Kentucky pastor Jamie Coots certainly said that it happened on multiple occasions in his church, according to NPR. Yet, he and other pastors have claimed that many people have walked away from the strikes, oftentimes declining emergency medical attention and antivenin. What's more, they say, many have survived (it's worth noting again that Coots himself died of a rattlesnake bite delivered during a 2014 church service, per ABC News).

But, for those lucky parishioners who are bitten but don't die, what's going on? For believers, of course, it's all to do with their own strength of faith and God's protection. Yet, others require a more concrete scientific explanation, which may lie in the state of the snakes themselves. Herpetologists speaking to NPR note that malnourished, poorly cared-for snakes may not be able to deliver much venom in a single bite. The Mountaineer also suggests that snakes may have released most of their venom in an earlier strike, meaning that they are effectively firing blanks when someone is bitten later.

Many argue that it's wrong to dismiss snake handlers as irrational

As an outsider, it's easy to see the practice of snake handling as a kind of religious sideshow, one that showcases backwards beliefs and plays into stereotypes about uneducated backwoods hillbillies. But to indulge in this sort of thinking is to skip over both the sincere belief of practitioners and the oftentimes complex and carefully considered thought process that would lead someone to carry a venomous snake as an act ultimately meant to bring glory to God.

First, there's no real reason to think that people believe they are completely protected from the consequences of a snake bite. Professor Brian Pennington, speaking to USA Today, says that many believers understand snake handling to be a command of God, given references to the practice in various Bible verses. However, they also acknowledge that they could very well be injured or die in the attempt. Handling snakes, then, is a demonstration of their obedience to God's will. For them, it's an informed decision that purposefully demonstrates their commitment to their faith.

And that faith is no joke. According to Sojourners, modern day members of snake handling churches may want to practice their religion in a way that deals with real consequences. Other congregations may seem to be only halfway committed and never fully test themselves or commit to what others will say is the "truth." Anything less is denying the "whole gospel."

Snake handling has become a thorny legal issue

Snake handlers may have a rich history and some deeply held personal and social reasons for picking up a bunch of rattlers and other venomous snakes. But, for legislators and law enforcement, there's still a pretty clear line that people shouldn't cross: don't touch those snakes.

According to The First Amendment Encyclopedia, snake handling has been subject to various legal challenges and laws throughout the years. While most laws and lawmakers acknowledge that freedom of speech and religious belief are indeed protected under the U.S. Constitution, they also argue that regulating a person's actions in the interests of public health and safety are a different matter.

That doesn't mean that legal challenges don't arise, of course. According to ABC News, pastor Andrew Hamblin was charged with illegally possessing dangerous animals in November 2013, after state wildlife officials seized an estimated 50 venomous snakes from the preacher. Hamblin pleaded not guilty and argued that the state was violating his First Amendment right. However, as the case was eventually dismissed, the legal challenge remained unsolved. The debate over the legality of snake handling is, for some, still very much ongoing.