Things Most People Get Wrong About The Bible

The Bible forms one of the foundational texts of today's culture and society. It has helped create the dominant cultural milieu, moral framework for the American Constitution, and contributed numerous idioms that English speakers, both Christian and not, unknowingly use daily. Because it is such an important text, it continues to be an incredibly important influence on societal discourse in spite of Christianity's numerical decline, and one of the most controversial.

Because the Bible is so polarizing, it is also one of the most misunderstood and twisted books. Politicians, pundits, and ideologues alike use and abuse it to cherry pick verses to suit secular agendas. These repeated abuses of the Bible have churned out misinterpretations in debates on public morality, law, and the culture wars of recent years, leading to a general misunderstanding of the text's contents. Below are some of the most common misconceptions that pervade the general public about the Bible.

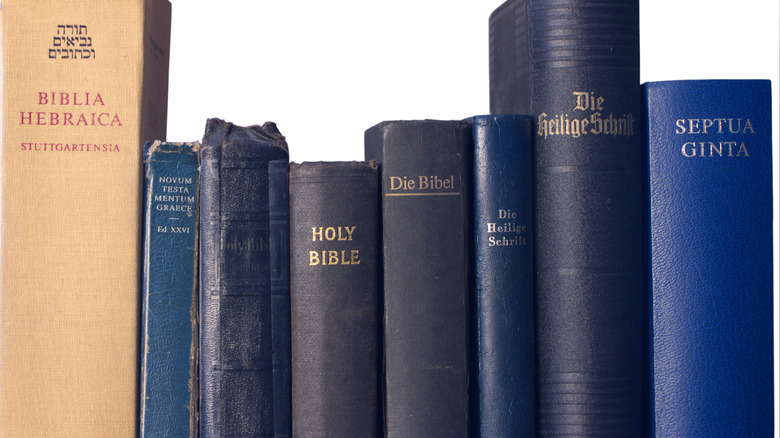

The Bible is a multilingual, cross-temporal library

Today, the Bible is seen as one book. But according to the BBC, the Bible is a multilingual library spanning 1,000 years and three languages. The first section of the Bible, the Old Testament dates to around 1000 B.C., reports Live Science. According to Bible Gateway, the Old Testament is mostly in Hebrew, the language of the Israelites. The last seven books, the infamous Deuterocanonical Books, however are extant in Greek. As My Jewish Learning explains, fourth century B.C. Jewish elites adopted Greek to interact with the rest of the Hellenistic world, leading to the translation of Jewish texts into Greek. The New Testament was also written in Greek, but in order to reach the wider non-Jewish audience that did not speak Hebrew.

Alongside the well-known languages of Hebrew and Greek is an oft-overlooked third tongue — Aramaic. Surviving today among the Middle East's Christian minority, Aramaic was once the Middle East's prestige language. The Deuterocanonical Books, according to EWTN, were likely translations of Aramaic originals, reflecting the native language of their writers. From this web of languages and traditions, a single volume was eventually created. But surprisingly, it happened well after Christianity took root in the Mediterranean.

The Bible post-dates Christianity by four centuries

The Protestant practice of Sola Scriptura, which sees the Bible as the only, inerrant source of God's teaching (and therefore the guide for early Christians), has created the idea of the Bible as a singular tome, especially among American Christians. In reality, though, the Bible as it is understood today did not exist when Jesus established his church on earth nor after his crucifixion.

According to historian Elaine Pagels, the march towards a common canon was littered with problems. After Jesus' death and resurrection, numerous, often contradictory gospels circulated in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially Egypt. These Coptic-language texts, called "gnostic gospels," promoted the idea of "hidden knowledge" rather than obedience to a deity. Mennonite scholar David Ewert noted that there also existed books cited in the Bible or by the Early Church Fathers that some Christian communities considered scripture. At the end of the fourth century A.D., two church councils sought to end the confusion by standardizing what is today called the Bible.

In 393, the Synod of Hippo achieved what previous councils had not. It agreed upon an Old Testament standard of 46 books. The Synod of Carthage four years later set the New Testament canon at 27 books. Gnostic texts such as the Gospel of Thomas were rejected due to heretical material (Jesus killing childhood friends), questionable origins, or other inconsistencies. The final result was a 73-book volume. But it would not be the last time it received a major edit.

There are two major versions

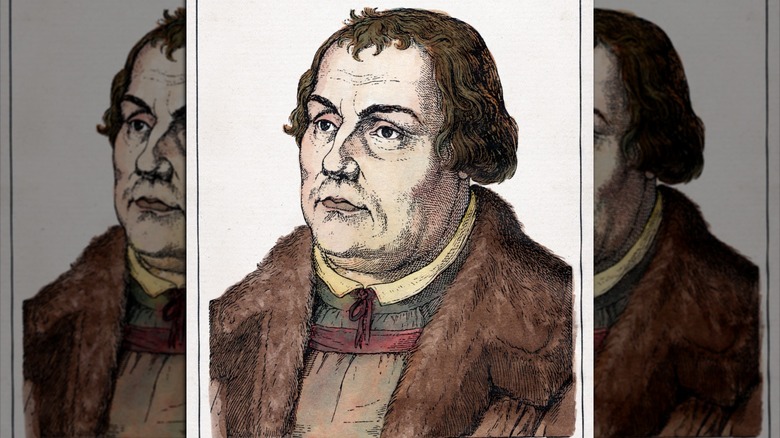

Catholics and Protestants do not see eye-to-eye on many issues. One would think, though, that they would agree on the number of scriptures. After all, the Bible is the Bible, right? Not exactly. A cause for frequent misunderstandings on both sides, Catholics and Protestants actually use different Bibles thanks to Martin Luther's changes in the early 16th century.

The National Catholic Register argues that Luther removed the Deuterocanonical Books from the Bible, reducing the total from 73 to 66 books, because he believed they weren't "what God really wanted." Nathan Busenitz of The Master's Seminary rejects accusations that Luther modified the Bible or "cut books." Luther conformed his Old Testament to the Jewish Hebrew Bible, which does not contain the seven Deuterocanonical Books. His opinion was that if Jesus, a Jew, affirmed only 39 Old Testament books, then the others were not scripture.

Nevertheless, Protestant Bibles include the Deuterocanonical books in appendices as worthy of a believer's attention, while ecumenical Bibles place them at the end of the Old Testament. The Catholic Church, meanwhile, solidified their status as scripture at the Council of Trent in the 16th century, cementing today's division.

Jesus appears in the Old Testament

According to the Jewish Voice, a popular misconception among both Christians and Messianic Jews is that only the New Testament is about Jesus because he does not appear in the Old. But Christianity believes that the whole Bible is about Jesus, notes The Gospel Coalition, and scholars have poured over the Old Testament looking for him there. The conclusion? Jesus makes multiple cameo appearances in the Old Testament. They just hide behind English translations.

The Jewish Voice notes that Jesus' Hebrew name Yeshua is translated as "salvation" some 150 times in the Old Testament. So the phrase "the Lord is my salvation" can technically be read as "the Lord is my Yeshua/Jesus." In a Christian worldview, this makes sense. Jesus is the savior of mankind, so his name should be a byword for salvation. Whether this counts as an appearance is debatable, but his name is definitely there.

Jesus also physically appears in the Old Testament, just not in human form. According to St. Justin the Martyr (via Bible Society), the Angel of the Lord in Genesis was likely an early appearance of Jesus. Walter Kaiser Jr. of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary also sees Jesus as the voice behind the Burning Bush that spoke to Moses, among a few other occasions. Unlike the appearance of Jesus' name, none of these are 100% settled in any Christian denomination, but are interesting nevertheless.

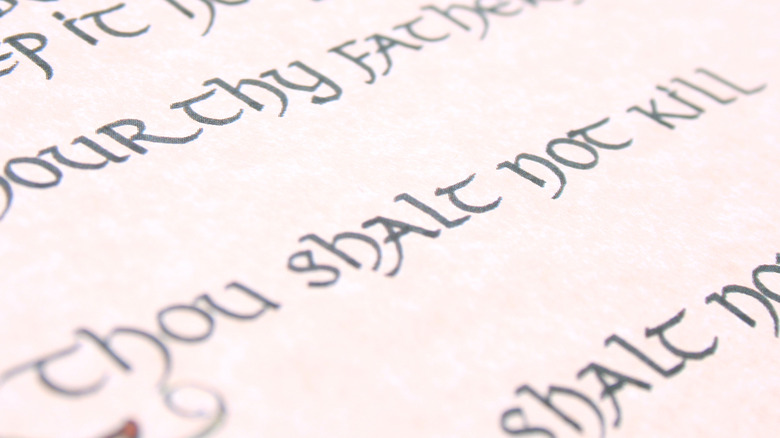

Thou shalt not murder

The Fifth Commandment (Sixth for Protestants) has recently become a political weapon among and against Christians in the debates on abortion, capital punishment, self-defense, and war. Most know it as "thou shalt not kill." In a nutshell, human life, made in God's image, is sacred. Therefore killing must be forbidden, right? Pope Francis would agree in part, having recently condemned the death penalty as a violation of the right to life. But is the commandment the blanket statement it appears to be?

According to the Jewish Magazine The Forward, the original Hebrew command is restricted to the killing of innocents. Matters such as self-defense, war, and capital punishment are governed by a different set of rules, a view most Christians maintain today. That said, the Forward notes that even Jews have debated the commandment's meaning, so Bible translators sometimes left the commandment purposely ambiguous.

In a historical context, Catholics and many Protestants interpret the commandment as "thou shalt not murder." From the Catholic perspective, the idea of a crusade for instance, ideologically conceived as a defense of Christendom against Islamic expansion, does not run counter to this commandment. Neither does the death penalty, which Christianity has historically supported.

Lord does not always mean the same thing

Readers of English Bibles will notice the appearances of the words Lord, lord, and LORD in the Old Testament. This confuses even Christians, as noted by the Christian Courier, and does not, at first glance, seem to have a purpose. But it is actually an example of translations attempting to convey original Hebrew nuances that are lost in English.

Written "Lord," the word is one of God's titles (in Hebrew, it's "Adonai"). When written LORD (or lord), it refers to God's name. So why not just write out the name of God? It seems easier than creating this confusing trifecta of uses with one word.

The reason is Jewish tradition. Haaretz notes that although Jews did not (and still don't), out of reverence, pronounce God's name YHWH under any circumstances, the scriptures and prayers containing it still had to be read or recited aloud. Therefore, Jewish scribes noted that YHWH should be read aloud as Adonai, a workaround that is preserved in Bible translations today. Christian Bible translators imitated the convention, translating YHWH as LORD rather than writing out God's name, whose exact pronunciation is unknown. This neat but misunderstood distinction ties Christianity with its Jewish roots and explains one of the Bible's more mystifying conventions.

The Philistines were not very philistine

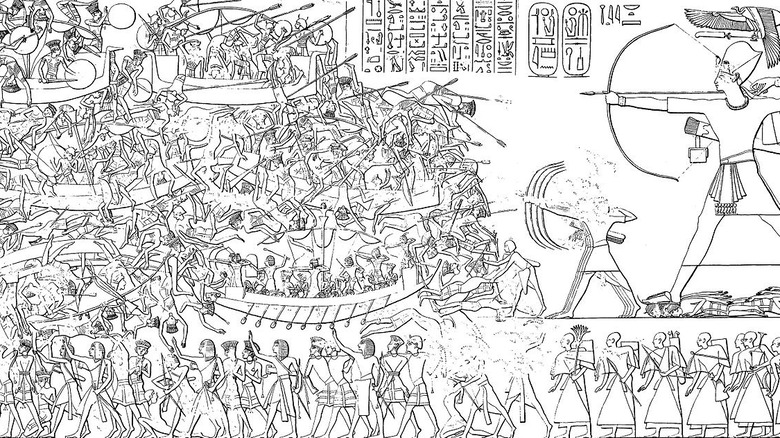

The word "Philistine" originally referred to Israel's chief enemies in the Promised Land. Because they are one of the primary villains in the Old Testament, their name, according to Merriam Webster, is a byword for uncouth, uncultured people. However, this view of the Philistines has its origins in 17th century Germany, and is not biblical. The Philistines were actually quite civilized, as recent archaeological evidence attests.

The Christian Science Monitor reported in 2016 that a team of archaeologists working near the city of Ashkelon discovered a large Philistine cemetery dating to around 1000 B.C. The site was hidden to prevent Haredi Jewish protests, but the team eventually released its findings, which were nothing short of spectacular. Among the finds were large storage jars, imported pottery, perfume, fragrant oils, and jewelry. The Smithsonian notes that the grave goods were strategically arranged for the benefit of the dead. The perfume was placed on the dead person's face near the nostrils so the tomb owner could smell the fragrance in the afterlife.

The careful and reverent treatment of the dead, who were equipped with the most sumptuous and exotic goods of the era, debunks the idea of the Philistines as savages. Instead, it points to a civilized foreign culture that had been inherited from the great Bronze Age civilizations of Greece and Crete.

They were probably European

The word "Philistine" in Arabic means "Palestinian." As a result, ferocious political debates have attempted to connect the modern Palestinians with the Philistines to establish some sort of continuity in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These debates are not only ahistorical, they also obscure the Philistines' fascinating origins, which are found in the Bible.

According to the Bible, the Philistines originated in Caphtor (probably Crete), and they were a "sea people" from the Aegean (via Purdue). Genetic testing on the bodies in the Ashkelon cemetery supports this notion, having determined that the Philistines probably originated in southern Europe, such as Greece, Spain, and Sardinia (via Smithsonian Magazine), and migrated somewhere between the end of the Bronze Age to the early Iron Age.

The genetic studies suggest that the Philistines were a result of a sea migration. The Smithsonian also reports that the Philistines were genetically very similar to their Levantine neighbors. However, they crucially also carried DNA from southern Europe and the Aegean. Most likely, these migrants had settled in the region and intermarried with local women. So potentially the Philistines were actually heirs of the first Greek civilization, not the uncouth barbarians the Bible makes them out to be.

King David was probably real

Millions of American children are familiar with the classic underdog story of the shepherd boy David and the giant Goliath. According to the Bible, David killed Goliath with a slingshot and became king of Israel (via National Geographic). It seems too good to be true, especially since according to Sci-News, scientists and historians generally have rejected David's very existence. But evidence from the Middle East suggests that even if he did not kill Goliath, he was a real person.

According to Biblical Archaeology, the strongest evidence for David in the textual record comes from the Israelites' enemies. The Tell Dan Stela, belonging to Hazael of Damascus, describes how he defeated a rival king of Judea of the "House of David." Now, this stela is fragmentary, and the reading has been challenged, but it is not the only appearance of David's name.

There is a second possible attestation of David's name, although it is admittedly less clear. According to Egyptologist Ken Kitchen (via Deseret News), there is a possible mention of a place called the "heights of David" in a list of place names engraved onto the walls of the Egyptian Temple of Karnak. This one is contested because one sign is too damaged to be read with full certainty. But, in light of the mention of David in the Tell Dan Stela, King David seems less mythological, reminding readers that religious questions aside, the Bible does contain accurate historical accounts.

The New Testament does not abrogate the Old

The Evangelical Gospel Coalition notes that a popular misconception regarding the two parts of the Bible is that the New Testament does away with the Old. This view primarily stems from the stark difference between Jesus' message of salvation and forgiveness on one hand and Old Testament Jewish Law on the other. Now, Jewish law was harsh. The notorious Levitical Laws proscribed the death penalty for a range of moral offenses, sometimes by burning or stoning the transgressors. The law also mandated reciprocal justice (an eye for an eye) for interpersonal crimes. So what does the Bible itself say about this controversy?

According to the Bible, the Old Testament was not abrogated. Jesus stated in no uncertain terms in Matthew 5:18 that "not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished." So the New Testament clearly gives Jesus' approval to the content of the Old Testament. So why don't the old penalties apply? The Catholic Church (via Catholic Culture) explains that Jesus took upon himself all of the sin (moral violations of the law) and suffered the penalty, which was death. Thenceforth, the penalties for violating the law were no longer needed because Jesus had already suffered them.

The Immaculate Conception is not the Annunciation

According to the Huffington Post, the Immaculate Conception is largely misunderstood. Popular wisdom holds that since Jesus' mother was the Virgin Mary, his conception was immaculate and free of sexual relations. This is a near-universal Christian belief, but it is not the Immaculate Conception. It is the Annunciation. The Immaculate Conception is an exclusively Catholic dogma concerning the Virgin Mary's conception.

The phrase "Immaculate Conception" posits that God shielded the Virgin Mary at her conception from original sin (also a Catholic term). Catholics believe that humans are born with sin inherited from Adam's disobedience to God in the Garden of Eden. Baptism washes it off. But Mary suffered from none of this. The Catholic reasoning, per the National Catholic Register, is that Mary needed to be sinless in order to be Jesus' (God's) mother. Thus, not only did she never commit any sins in life, she could not have been born with any sin either. That would have negated her purity.

Unlike the Annunciation, which does appear in the Bible, the Immaculate Conception does not. Instead, the dogma developed in Western Europe during the Middle Ages before being defined under Pope Pius IX in 1854. Protestants view the dogma as unbiblical papal overreach, while the Eastern Orthodox Church rejects the dogma as unnecessary.

The three kings were not kings

The well-known Christmas carol "We Three Kings" is a holiday favorite. Three kings from the East came to adore the infant Jesus and bring him gifts. But this famous phrase does not appear anywhere in the Bible, and according to Catholic Encyclopedia, is completely absent from early Christian writings. National Geographic notes that the Bible does not even mention how many of them there were.

If the three kings were not kings, then who or what were they? English Bibles call them "Wise Men from the East," which in Jesus' time meant the Iranian world. In a nod to their Persian background, they are sometimes referred to as the magi, which Encyclopedia Iranica notes was the Persian word for a Zoroastrian priest. The Parsi Times notes that these astrologers had a keen interest in the Star of Bethlehem, while the Gospel of Matthew suggests that they were among Jesus' first believers. But why a group of Zoroastrian priests cared about Jesus in the first place, no one knows for certain.

The story of the Three Kings draws heavily on inference and tradition, as well as the Bible. The canonical story, which states that there were three, is an example of this. Because the magi brought Jesus three gifts, it was inferred, according to Biblical Archaeology, that there must have been three of them. However, some Syrian sources give numbers as high as 12. But inconsistencies of these sorts are expected from a story that draws so heavily on oral tradition.