Places On Earth We Still Haven't Explored

Adventurous people out there have the resources to explore the farthest reaches of the Earth. But while it seems every last spot will get explored, researched, and photographed, there do remain some places that have barely been touched — or haven't been seen at all. From the deepest depths to the highest peaks, these virgin territories are still out there to spark your imagination and wanderlust.

Gangkhar Puensum, Bhutan

This impressive peak on the border of Tibet and Bhutan is the 40th-highest-mountain in the world and has yet to be summited. According to historical records, aspiring climbers of days past had trouble even locating the 24,280-foot mountain. Maps were pretty inaccurate for quite a long time, and even after people knew where it was, it still proved impossible to conquer between the cold and the wind and this one really, really steep ridge. In 1985, a team from Britain attempted the climb, but illness forced them back. In 1986, a monsoon stopped an Austrian climbing team.

In 1987, the government in Bhutan banned climbing Gangkhar Puensum because powerful spirits are said to inhabit the mountain's peak. Some cite stories of strange lights, ghostly figures, magnetic anomalies, and even Yeti on the way up the allowed 6,000 meters from the top.

Undeterred by the rumors, a Japanese group of climbers got permission from the Chinese Mountaineering Association to climb the unclimbable mountain from the Tibetan approach. The Bhutanese side disputed this permission, and the group settled for climbing the peak near Gangkhar Puensum, known as Gangkhar Puensum North. Although that peak was also previously unclimbed, the climbers were a bit grumpy about the whole thing. Still, no one has gotten as close as they did, and it's possible no one ever will.

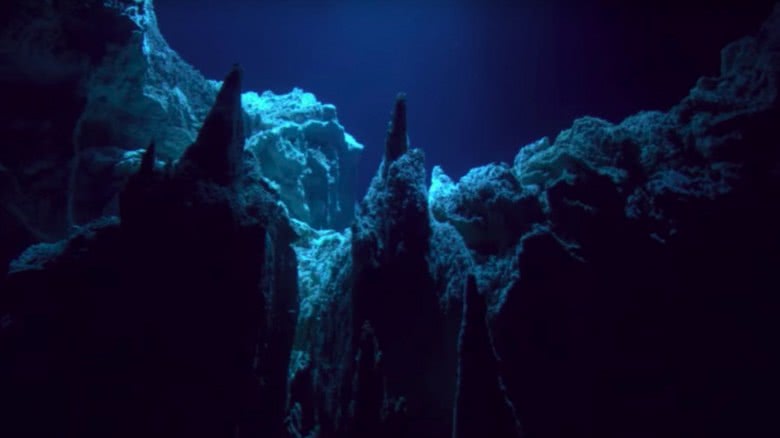

The eerie graveyards of Earth's underwater caves

You've probably heard the phrase "the age of exploration." It refers to the hundred or so years when Europe got really into the pastime of finding new parts of the Americas untouched by white dudes and then intentionally giving smallpox to the non-white dudes already living there. Sounds ... inspiring? Well, fear not, romantics who wish you still lived in these virgin times. By some measures, humanity is in the middle of a brand new age of smallpox-less exploration right now.

Planet Earth is riddled with caves, a good proportion of which have spent a few dozen millennia submerged underwater. Until very recently, that meant they were inaccessible to anyone but the suicidally insane, plus Aquaman. And Aquaman is way too busy starring in a sinking movie universe to search every cave. Which is why what's been happening this past decade is so fascinating. Utilizing state of the art diving equipment, adventurers have started exploring Earth's drowned caves (via adventure magazine Outside). What they've found is already rewriting history.

From Africa, to the Americas, to Europe, underwater caves have been found filled with perfectly preserved skeletons of animals we haven't seen for ages. These finds are helping scientists better understand how certain species evolved, and exactly what the planet used to look like. The best part is humanity has still explored only a fraction of the underwater caves out there. Star Trek was wrong. The final frontier is really here on Earth.

The Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is located off Japan in the Pacific Ocean and is the deepest place on the entire planet. Just to give some perspective, the Indian Ocean is 12,740 feet deep, with its Java Trench at 25,344 feet deep. The Atlantic Ocean is 12,254 feet deep with its Puerto Rican Trench at 28,374 feet deep. The Pacific Ocean is 12,740 feet deep, and the Mariana Trench is a staggering 36,201 feet deep. If Mount Everest were placed at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, it would still have 7,176 feet of water above it.

The trench was created when one tectonic plate topped with oceanic crust slid under another. It was first discovered in 1951 by the HMS Challenger II, which is why the deepest point is called Challenger Deep.

In 1960, Swiss scientist Jacques Piccard and U.S. Navy Lt. Colonel Donald Walsh traveled to the bottom of Challenger Deep in a submarine designed by Piccard's father that used gasoline in its floats because gasoline is lighter than water. More recently, film titan James Cameron launched an expedition to the floor of the Mariana Trench called DeepSea Challenge. Cameron himself traveled to the bottom in a custom submersible that he helped design, and he took cameras, unlike the 1960s expedition. He filmed lots of squishy creatures, and maybe helped discover a new species of sea cucumber. But even still, the Trench is almost entirely unexplored.

Inside Venezuela's impossible tepuis

If you've ever opened a South America guidebook, you'll know what a tepui is. These gigantic towers of rock with sheer sides that rise out the ground like God has decided to just start messing with scientists are found across Venezuela. They're incredibly remote and seriously hard to climb.

But while there are likely tepuis which still have yet to experience sweaty adventurers standing on their summits, humanity has at least flown drones over most of them. The real virgin territory comes much lower down, inside. Hundreds of tepuis are riddled with cave and crevice systems so isolated from the world that they've evolved parallel ecosystems. According to New Scientist, only a fraction of them have ever been explored, and many of those by a single man.

Meet Francesco Sauro of the University of Bologna. For the last decade, he's been traipsing through the mysterious worlds inside tepuis, where the walls are pink, where undiscovered bacteria lurk, and where you can find minerals that have never been documented before. However, there are plenty even Sauro hasn't gotten inside. Many tepuis are only accessible from holes in the top, requiring dangerous helicopter landings in a part of the world known for extreme weather, in a country that's a model of political instability. You might die trying to get inside, but at least you'll die knowing you were first.

Oodaaq Island, Greenland

There are six total "visited" islands north of Kaffeklubben, Greenland. "Visited" means that someone, at some point, set foot on them, but whether they still exist is up for debate. Confused? Read on.

Take, for instance, Oodaaq Island. It was discovered in 1978 by Uffe Petersen, a Danish scientist mapping north Greenland with his team. They were hanging out on Kaffeklubben, thought to be the northernmost of the Greenland islands, when they saw a speck out yonder. North! They flew over, and sure enough, there was an "island" there. Well, really a gravel bar, but it counted. Petersen named it after an Eskimo sledge driver who'd been part of Robert Peary's North Pole expedition in 1909. While some sources say it hasn't been seen since it was discovered, that's not technically true.

Fast-forward to the early 2000s, when Dr. Peter Skaffe, a Danish anthropologist, was filming and studying the northern islands. Even though an expedition in the sea north of Kaffeklubben saw no trace of Oodaaq, Skaffe found that only eight days later, his camera had caught a glimpse of the small island. Want to see it? Well, if sea levels continue to rise, it might be best to hang on Kaffeklubben instead and check out the crazy arctic flowers.

The vast majority of Earth's mountains

In 2014, BBC Future sat down with the chairman of the Mount Everest Foundation screening committee, Lindsay Griffin, for a piece on mountains humanity had never climbed. While Griffin identified many well-known unclimbed peaks (say hello again to Gangkhar Puensum!), there was one point he made that should give every wannabe explorer pause for thought. According to Griffin, "there are infinitely more unclimbed peaks than there are climbed ones." In fact, there are so many we don't even know how many there are.

Griffin should know what he's talking about. When the BBC spoke with him, he had "at least 65" previously unclimbed mountains under his belt. His method? He just identified the untrendy peaks and climbed them. Since they're not the highest or hardest, most of these mountains are basically ignored by the world. Yet, as far as anyone can tell, they've never had a single human set foot on their summits.

This surplus of unclimbed mountains makes sense when you think about it. There are whole chains in, say, Antarctica that are so inhospitable to life only an idiot would attempt summting them and risking the wrath of the Shoggoths inside. But there are other peaks, too, that are less hard to get to, but simply remain unclimbed for the same reason you've probably never gone to Delaware: Why bother? It may not quite have the glamour of discovering a new continent, but, hey, beggars can't be choosers.

Machapuchare, Nepal

In the Annapurna Himalayas, there's a sacred mountain that the Nepalese have made off limits to climbers. It's called Machapurchare, or "Fish Tail Mountain." In 1957, Wilfrid Noyce and A.D.M. Cox climbed Machapuchare, but they didn't go to the top. They could have — Noyce was one of the first to climb Everest. But this mountain is sacred because Lord Shiva lives on the top, and that's pretty serious. Nepal's king asked Noyce and his partner not to go all the way up, and they agreed.

Climbers say Bill Denz, a rogue climber from New Zealand, didn't give a hoot about what the Hindus held sacred and went all the way to the top in the early 1980s. Denz died on Mansaw, another Himalayan mountain, in 1983, so we'll never really know for sure. We have a written account, however, of Noyce's experience in his book Climbing the Fish's Tail.

While you can't climb this sacred mountain to its summit, you can do plenty in the base camp. And because the mountain is in a conservation zone and the peak's religious significance, Machapuchare is perhaps the last pristine mountain in the Himalayas. Humans would probabaly ruin it right away anyway. Mount Everest climbers have left behind 12 tons of human poo, 50 tons of garbage, and quite a few frozen corpses. We suck.

Northern Mountain Forest Complex, Myanmar

High in the mountains of Myanmar, the Hkakabo Razi National Park and Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary make up the Northern Mountain Forest Complex, and the World Heritage Convention has proposed expanding it to create an area of over 7,000 square miles.

A Cambridge study found that less than 1.4 percent of the existing forest area in this region of Myanmar is affected by humans, which is pretty extraordinary, though this does not include hunters. So, when we say this area is unexplored, it means the flora and fauna and wildlife have not been studied, and the area has not been explored by scientific or climbing communities. That doesn't mean poachers out for tiger parts and other animal products to sell in China haven't set foot in these lush and vibrant forests.

Even though almost half of Myanmar is still covered in forest area, deforestation is a real problem, as is the destruction of wildlife population. Scientists filmed some red pandas there in 2014, and their habitat is declining, largely due to illegal logging activity.

Antarctica's subglacial lakes

First discovered in 1973, massive subglacial lakes in Antarctica have fascinated scientists for years. While there are now 400 known subglacial lakes in the 5 million square miles of frozen area, plenty are not known. Also unknown are the ins and outs of the complex ecosystem that thrives under so many thousands of feet of ice.

It was very important to Russian scientists to be the first to get a sample from a subglacial lake, and they started digging into Lake Vostok in 1953. The drilling was suspended in the late 1990s, but it seems that they're making good headway now.

Another successful experiment was conducted on Lake Whillans by a microbial ecologist from Montana State University, John Priscu. He got a sample from almost a half mile under the ice and reported that the ecosystem was, indeed, absolutely thriving. While there's so much unexplored and unknown about these ancient, frozen lakes, they're on scientific radars across disciplines and countries, and it's expected that easier access will exist by 2035. So, that's one upside to the whole world melting.

North Sentinel Island

The Andaman Archipelago is in the Indian Ocean's Bay of Bengal. It lies in between Burma and Indonesia and contains about 200 islands, and in it, there's a little island, a little off to the west of the bulk of others, called North Sentinel Island. It's about the size of Manhattan and has between 50 and 400 inhabitants. Nobody knows for sure because the island is totally unexplored by Westerners. The local Sentinelese are notoriously resistant to any visitors whatsoever.

If the island is anything like the other islands in the region, it's home to unique flora and fauna. As of 2015, fishers looking for sea cucumbers (a delicacy in China) were trying to encroach on the waters around North Sentinel, but outside contact would be disastrous for the North Sentinelese. They have not built any immunity to diseases modern people carry, and interference could well wipe them out.

Of course, asking humans to just leave well enough alone is a tough sell.