History Of Crucifixion Explained

Arguably, no other symbol has become as strongly associated with the world's largest religion as the cross. In his book "Christianity: An Introduction," theologian Alister McGrath called it "the universally acknowledged symbol of the Christian faith." This isn't surprising, considering how the faith bases its tenets on the life and teachings of history's most famous crucifixion victim, Jesus Christ.

Before the rise of Christianity, however, the practice of crucifixion came with a terrible stigma. It was nothing more than a merciless form of punishment, reserved only for the dregs of society. The word "cross" traces its roots to crux, a Latin word that, in ancient times, simply pertained to "any object on which victims were impaled or hanged" (via the BBC). In fact, crucifixions before the time of Christ didn't even necessarily happen on crosses. According to some accounts, victims were just straight-up nailed to trees or structures; suspended helplessly, they were left with no choice but to endure the pain and die excruciating deaths.

To someone living in modern times, crucifixion may seem a tad too brutal and sadistic to still be used as a method of punishment. And while the history of crucifixion supports such an assessment, the practice has not yet faded into total obsolescence. Here's a look at how crucifixion began, its rise and fall in popularity, and the ways it is used in the present day.

How crucifixion became a form of punishment

It's not that easy to pinpoint exactly who came up with the practice of crucifixion to begin with. The Guardian attributes the invention of crucifixion as a method of punishment to the Persians, some time from 300 to 400 B.C. However, "The History and Pathology of Crucifixion" states that the Assyrians and Babylonians were the first ones to employ this torturous technique, with the Persians embracing it in 6 B.C.

Historical records indicate that the Roman empire was responsible for further developing crucifixion as a form of capital punishment (via the Guardian). Hanging on an upright wooden cross, crucified criminals usually suffered slow, agonizing deaths. The quickest deaths took only ten minutes, but some unlucky victims took up to four days to die. The actual causes of death varied. Some died due to the pre-crucifixion flogging they received, while others perished from internal bleeding and dehydration. Some died of heart attacks, while some slowly and steadily suffocated.

The earliest records of crucifixion

In his book "The Histories," the Greek writer Herodotus chronicled what many experts consider to be the oldest known incident of crucifixion, dating all the way back to 522 B.C. When Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, traveled to Magnesia upon the invitation of the Persian satrap (governor) Oroetes, the Persians killed him "in some way not fit to be told." Perhaps unsatisfied with the way he snuffed the life out of Polycrates, Oroetes took his dead body and crucified it.

Another early record of crucifixion as capital punishment is from 521 B.C. (via Livius.org). As told in an article on History of Yesterday, the King of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, Darius I, learned about how Arakha, a man claiming to be the son of a former king, led a revolt and subsequently declared himself the king of Babylon (while taking on the name Nebuchadnezzar IV). To reclaim the city from Arakha's forces, Darius I dispatched his bow-carrier Intaphrenes, who promptly defeated the self-appointed ruler on November 27, 521 (which was less than three months after Arakha claimed the throne). It's said that around 3,000 of Arakha's followers were crucified in the city. Darius I commemorated this victory by writing the following in his Behistun Inscription: "By the grace of Ahuramazda Intaphrenes overthrew the Babylonians and brought over the people unto me ... Then I made a decree, saying: 'Let that Arakha and the men who were his chief followers be crucified in Babylon!'"

How the practice of crucifixion reached Rome

While it's a bit complicated to trace the origin of crucifixion as punishment, tracing the path that it traveled to reach Rome is somewhat more straightforward.

According to CatholicEducation.org, the practice of crucifixion reached middle eastern Mediterranean countries through the efforts of Alexander the Great, the Macedonian ruler and commander who successfully established one of history's largest empires. A critical part of his military campaign was his triumphant siege of Tyre, Phoenicia's biggest and most significant city-state, in 332 B.C. (via WorldHistory.org). Under Alexander's orders, around 2,000 Tyrians were crucified on the beach. The conqueror subsequently introduced the practice to the neighboring Phoenician city of ancient Carthage.

Approximately one hundred years later, the Romans fought and eventually defeated Carthage in the series of clashes known as the Punic Wars. As LiveScience states, it was here when the Roman empire first caught wind of crucifixion. They ended up taking the practice with them back to Rome, subsequently developing it into an infamously brutal punishment method.

Was this the worst mass crucifixion?

Alexander the Great's crucifixion of 2,000 citizens during the Siege of Tyre may sound rather excessive, and it's unsettling to imagine that many bodies lined up and suspended from frames along the coastline. Shockingly, this incident isn't the worst recorded case of a mass crucifixion. That dubious distinction belongs to the mass crucifixions that happened in 71 B.C., which involved three times as many victims (via History of Yesterday).

In an interview with the BBC, classical historian Mary Beard recalled the story of Spartacus, a Roman gladiator who, alongside other gladiators, instigated a massive slave revolt called the Third Servile War. After Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus put an end to the slave uprising, he ordered his troops to take 6,000 of Spartacus' forces and crucify them along a 200-kilometer stretch of road connecting Capua to Rome, according to the records of historian Appian of Alexandria. Meanwhile, Spartacus' body was reportedly never found.

The offenses that got people crucified

When the Romans brought the practice of crucifixion home, authorities didn't roll it out as punishment for all offenders. As stated in a LiveScience article, crucifixion had a terrible reputation as "an extremely shameful way to die," and so the majority of Roman citizens who had committed crimes were spared from it.

Instead, the Roman Empire utilized crucifixion — which they saw as "a perversion of justice" if it were to be imposed upon an ordinary citizen — in punishing the undesirables and the disgraced in Roman society. These included soldiers who abandoned their service without authorization, non-Roman criminals, slaves, militants, rebels, and even Christians. Typical victims of crucifixion were accused robbers, according to The Guardian. The Roman Colosseum, the iconic oval-shaped amphitheater in Italy built in 80 A.D., became the site of such crucifixions (via Curious Historian).

One noteworthy example was when Antiochus IV Epiphanes, a king of the Seleucid Empire, punished Jews with crucifixion for not embracing ancient Greek customs. Another was when Roman general Julius Caesar, in an act of revenge against the Cilician pirates who had kidnapped him as a young man, captured them some time later and had them crucified (via Britannica).

How exactly does crucifixion kill?

From a purely visual standpoint, crucifixion looks like some truly nasty business: A victim is nailed to a tall cross, and left to hang under the blazing sun until they perish. Even more terrifying, however, is finding out exactly how a person dies from crucifixion.

The Guardian provides a closer look at what happens to a person while they're crucified. In some instances, the victim's hands are nailed to a horizontal piece of wood that bisects the vertical frame from which they're suspended. Nails approximately 7 inches dig deep into the victim's flesh, penetrating the wrists, paralyzing the hands, and forcing the bones to bear the individual's weight. (In more serious cases, however, the victim's arms are nailed or tied directly above their head, which makes breathing next to impossible.)

The victim's feet are then nailed to the vertical frame, with their knees bent at a 45-degree angle. The idea is that over time, the victim's entire weight would shift from the legs to their arms, lengthening them by up to 7 inches. Efficient (or perhaps sadistic) executioners reportedly broke the victims' legs to hasten the process. Sooner than later, the victim's own weight would cause their chest cavity to rise, effectively suffocating them. At this point, the victim may die of internal injuries, cardiac arrest, or asphyxiation.

Doing as the Romans do

As explained in "The History and Pathology of Crucifixion," the Roman Empire rarely pulled crucifixion out of its toolbox of capital punishment for Roman citizens, as it was considered far too brutal and embarrassing. It's not difficult to understand this viewpoint, based on the lengths that Roman executioners went to just to guarantee that the victims would actually die on their crosses.

Roman crucifixion guidelines prohibited the guards from leaving the crucified victims while they were still breathing. Unsurprisingly, this forced them to employ painful (and occasionally creative) ways to speed up the dying process, including "deliberate fracturing of the tibia and/or fibula, spear stab wounds into the heart, sharp blows to the front of the chest, or a smoking fire built at the foot of the cross to asphyxiate the victim." Despite the rather barbaric nature of the punishment, it still gained massive popularity among the Romans; one example was when a Roman general, Publius Quinctilius Varus, sentenced 2,000 Jews to death by crucifixion (via LiveScience).

That's not to say, however, that the Romans had a monopoly on this merciless method of execution. In fact, the enemies of the empire were reportedly more than happy to return the favor whenever possible. When Varus' forces were defeated in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, for instance, the victors, led by Germanic officer Arminius, crucified a good number of the Roman general's soldiers. (According to Smithsonian Magazine, Varus committed suicide.)

The crucifixion of Jesus

Without a doubt, the single most well-known and historically influential death by crucifixion was that of Jesus Christ. In their 2003 report, Francois Retief and Louise Cilliers wrote: "Christ was crucified on the pretext that he instigated rebellion against Rome, on a par with zealots and other political activists." The Gospels say that Jesus was arrested in Gethsemane, a garden in Jerusalem whose precise location is still debated.

According to CatholicEducation.org, the crucifixion of Christ followed what was the standard procedure of the era. The Gospels tell of how Jesus was tried by a Jewish judicial body called the Sanhedrin, after which he was taken to the court of the Judaean governor Pontius Pilate. Pilate proceeds to question Jesus, finding no grounds to charge the controversial figure with any case. Regardless, Jesus received the death sentence when the audience chose to free a bandit named Barabbas instead of the "King of the Jews" (which meant the latter's crucifixion).

The duration of time it took for Jesus to die on the cross was relatively short, and may be explained by a condition called hematidrosis. As defined in a 2103 paper in the Indian Journal of Dermatology, hematidrosis is the state in which an individual "sweats" blood due to the rupturing of their capillary blood vessels from severe stress. This explains why, when a Roman soldier pierced Jesus' side to check for signs of life, blood and water (likely serous pleural and pericardial fluid) came flowing out.

How crucifixion in Rome ended

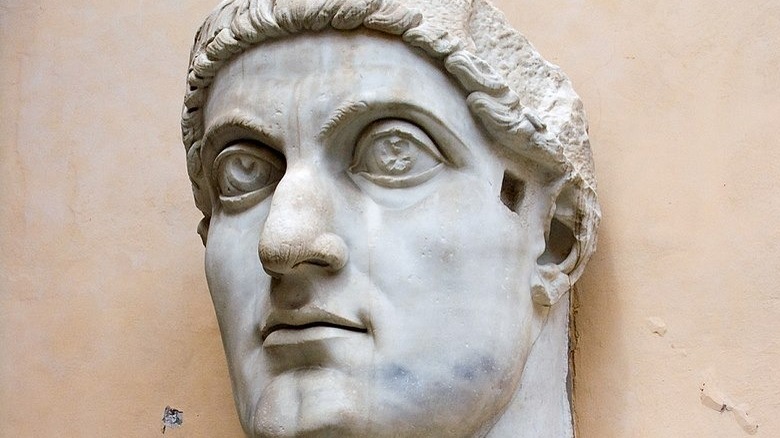

While it may have been the Romans who fine-tuned crucifixion as capital punishment, it was a Roman emperor who eventually outlawed its use, nearly 300 years after the death of Christ (via LiveScience). Some say that Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, abolished the practice due to his devotion to Christ. Interestingly, certain historical records suggest otherwise.

As the story goes, Constantine fought at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 armed not just with soldiers and weapons, but also with a vision: "a cross of light accompanied by the words, 'In this, conquer'" (via Slate). This not only prompted the leader's conversion to Christianity, but also supposedly enlightened him about the hardships endured by Christ. This, in turn, led to his decision to ban crucifixions in Rome. Some claim that he instituted hanging as a replacement, as one of many reforms pushing for humane treatment of criminals.

However, based on the account of Roman writer Julius Firmicus Maternus, crucifixions still continued in Rome for at least 20 years after the ban. Moreover, Slate reports that the "oldest unambiguous record of a crucifixion ban," the Code of Theodosius, is dated over a hundred years after Constantine's passing. Even the first person to write about Constantine's crucifixion ban, Aurelius Victor, didn't believe that Constantine's conversion led to his distaste for crucifixion; rather, the historian suggested that it was Constantine's sense of humanity that manifested in this decision, not his devotion to Christ.

Crucifixion and Islam

Believers of the Islamic faith have a different take on Christ's crucifixion: it didn't really happen (via the BBC). That's not to say, however, that they're unfamiliar with the practice. In fact, they have a word for it: Ṣalb, which quite literally means "crucifixion," according to Brill Online.

As Islamic scholar Dr Usama Hasan explained in an interview, some verses of the Koran, the holy book of Islam, talk about imposing crucifixion as a punishment for "those who wage war against Allah and His Messenger and strive upon earth [to cause] corruption." However, Hasan was also quick to clarify that, much like other verses in the book that talk about serious acts of harm or retribution, the verse pertaining to crucifixion was immediately followed by a disclaimer: "Except for those who return [repenting] before you apprehend them. And know that Allah is Forgiving and Merciful." Hasan even goes so far as to say that groups imposing such punishments in modern times are "un-Islamic," and that verses endorsing these acts shouldn't be read in isolation.

One recent case of crucifixion at the hands of Muslims happened in 2012, when a 28-year-old in Yemen was killed and hung on a cross after bugging vehicles with electronic trackers for U.S. military drones to trace and attack.

Crucifixions in Japan

Constantine the Great's ban on crucifixions in Rome didn't end the practice. In fact, it reached Japan during the Age of Civil Wars (1138-1560) an entire millennium later, as written by Charles A. Moore in "The Japanese Mind." Crucifixion allegedly resurfaced after three and a half centuries of Japan eliminating capital punishment. It is largely believed to have been brought back simply as a means of curbing the spread of Christianity in the country during this era, which started when Jesuits began their Japanese evangelical mission in 1549 (via Reuters).

It took less than a hundred years for Christianity to be banned in Japan, driving believers underground and missionaries out of the country until the ban ended in 1873. During this time, anyone caught adhering to the tenets of the Christian faith suffered a terrible fate: martyrdom on a cross. The most infamous instance took place in 1597, when 26 believers, including a 12-year-old boy, were crucified on Nagasaki's Nishizaka Hill (via Oratio).

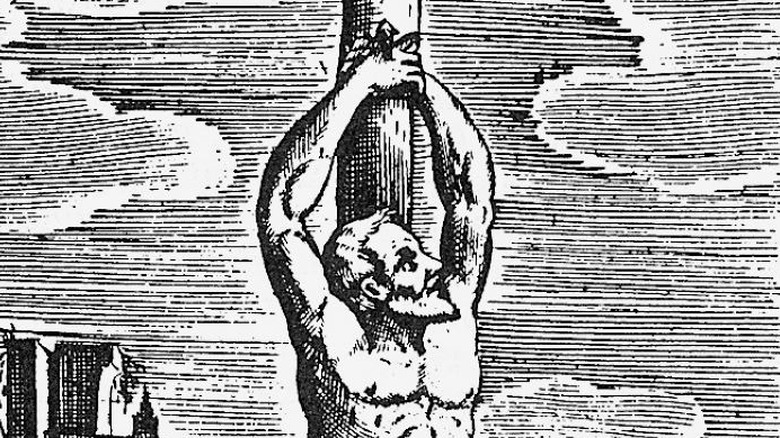

In the book "Capital Punishment in Japan," Petra Schmidt describes the process of crucifixion in Japan. First, the criminal would be paraded around town riding a horse (hikimawashi), then tied to a cross, gored with spears, and then stabbed through the throat. The body would only be taken down three days later. There were also some equally horrible variations, like sakasaharitsuke (upside-down crucifixion) and mizuharitsuke (water crucifixion).

Does crucifixion still happen in the modern world?

Despite its barbaric nature and disturbing history, crucifixion has survived as a practice well into the 21st century. However, it isn't always used as punishment for criminals; some voluntarily undergo it as a test (and display) of their faith in Jesus Christ.

According to Slate, Saudi Arabia still enforces crucifixion as a form of punishment; typically, rape and other grievous offenses merit this sentence. The same source reports that Middle Eastern crucifixions sometimes start with the criminals already dead (or worse, beheaded), with the crucifixion itself serving as a means of publicly displaying the offender's corpse. Additionally, during the early half of the 20th century, some women in Russia were crucified after being accused of practicing witchcraft. As for the United States, crucifixion is an obsolete practice, with lawmakers rarely putting forward any serious suggestions toward its revival.

In the Philippines, however, crucifixions happen at least once a year, as part of the Catholic celebration of Holy Week (via CNN). On Good Friday, believers dress up as Christ and subject themselves to public flogging and crucifixions, serving the twofold purpose of displaying their faith and atoning for their sins during the previous year. It's worth noting, however, that the Catholic Church doesn't endorse this tradition (which traces its roots to a local play about Christ written in the 1950s).