What Really Happened During The Great Binge?

Coined in the 21st century, the Great Binge refers to a period of time in Europe and North America from 1870 to 1914 when there was an explosion in the availability of various drugs. When you hear stories about heroin and cocaine being sold at every pharmacy around the corner, that took place during the Great Binge. When Sherlock Holmes was deciding whether he was going to shoot up heroin or cocaine, that was during the Great Binge.

People were able to get their hands on cocaine, heroin, opium, absinthe, and more with relative ease. Due to their widespread availability, everyone took part in the Great Binge. But ultimately, it's unknown exactly how many people worldwide were addicted to drugs during the Great Binge.

By the 1920s, an anti-drug crusade led by the United States and fueled by xenophobia and racism would cause the heroin cough drops and cocaine tablets to disappear from store shelves and bathroom cabinets. But while it lasted, the Great Binge was a time of true intoxication. Here's what really happened during the Great Binge.

Before the 1868 Pharmacy Act

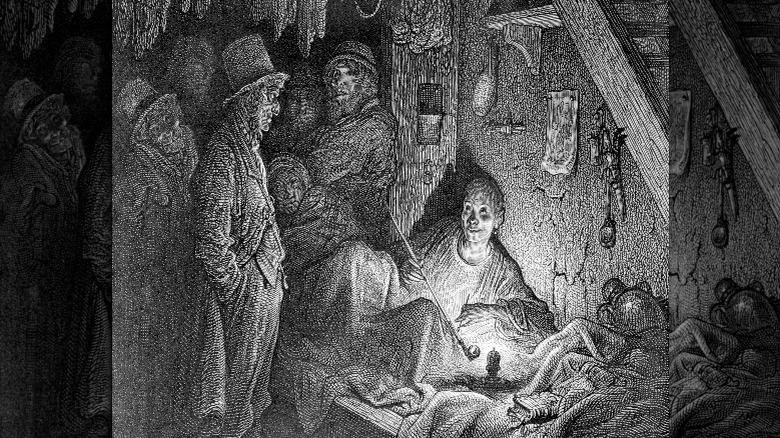

Up until 1868, when the Pharmacy Act was passed in the United Kingdom, opium could be obtained almost anywhere by anyone. The situation was no different in the rest of Europe or the United States, where laudanum, a tincture of opium dissolved in alcohol, would be kept around the house for anything from headaches and insomnia to diarrhea and cholera. WBUR writes that it was kept on hand "the way we keep Tylenol [or Ibuprofen] today."

The British Levant Company and the British East India Company were responsible for the import of opium around the world, and up through the 18th and 19th century, they were heavy suppliers. Between 1827 and 1842, it's estimated that over 27,000 pounds of opium came through U.S. ports. According to the British Library, opium was sold by stationers, tobacconists, barbers, confectioners, and ironmongers. And it was frequently prescribed to both adults and children for even the most basic ailments such as the hiccups.

But eventually, the distribution of opium was restricted through the 1868 Pharmacy Act. This happened mainly because of racist associations with Chinese opium dens and fears of white women being corrupted by "foreigners," as well as classist associations with the working class. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents' Journal writes that economic and intentional pressure also played a role, as did doctors and pharmacists who were "interested in safeguarding [their] role as gatekeepers to medicine."

Opium for babies

Although opium was restricted in terms of who got to distribute it, it was still given out relatively freely to people of all ages, including babies. Infants were frequently given laudanum, often as a distraction during teething or just as a way to subdue the baby, especially in foundling hospitals. According to the Museum of Healthcare at Kingston, in 1873 it was suggested that 6-month-old babies should get between two to three drops of laudanum, but higher dosages were often given.

Some parents even used it when they couldn't find someone to watch over their child. The Saturday Evening Post reports that one parent in New England used it to put her children "into a deep sleep" so she could go to prayer meetings in the evening.

However, as The Register and Library of Medical and Chirurgical Science notes, "the mortality of infants caused by [laudanum] is incalculable." According to Live Science, in the late 1800s, "narcotic deaths" was added as a category to the Registrar-General Reports in England, which recorded population statistics annually, and between 1863 and 1867, 236 narcotic deaths were reported in infants younger than 1 year old.

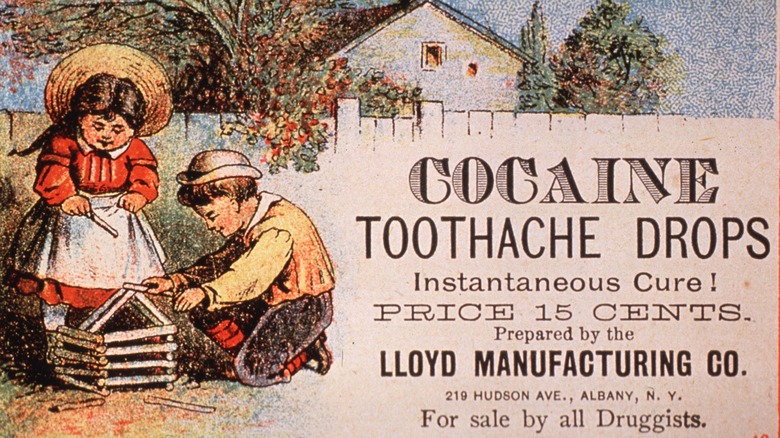

The many medical uses of cocaine

Coca leaves have been brewed and chewed for various reasons by numerous indigenous groups in South America for thousands of years, but the substance known as cocaine wasn't first isolated until 1860 by German chemist Albert Niemann. And within 20 years, it was being used and prescribed by doctors for a variety of reasons.

Mental Floss writes that cocaine's effect as an anesthetic was quickly noticed and soon it was being used as a topical anesthetic for things like eye or throat surgery. And cocaine wasn't just for serious ailments. It was advertised as a cure for basically anything, including "hemorrhoids, indigestion, appetite suppression, and fatigue," and Freud even suggested it as a therapeutic drug for depression and alcoholism. Lozenges with cocaine were sold for toothaches and cocaine was even used as "a cure for shyness in children," according to "Cocaine Nation."

The United States Hay Fever Association called cocaine their "official remedy" in 1884 and this recommendation carried into the beginning of the 20th century. In the 1890s, the Sears Roebuck catalogue advertised a cocaine kit with its own hypodermic syringe for $1.50. And by 1900, a gram of cocaine could be bought at any pharmacy in the United States for 25 cents.

Coca-Cola Classic

John Stith Pemberton was trying to create a morphine substitute to combat his own addiction, and it was in this process that Coca-Cola was invented. Originally known as Pemberton's French Wine Coca, the syrup was made out of kola nuts and coca leaves, said to be a remedy for ailments ranging from headaches to morphine addiction. The name Coca-Cola came from Frank Mason Robinson, Pemberton's bookkeeper, who suggested the name based on the drink's two main ingredients, according to Rewind & Capture. The name change came out of the alcohol prohibition in Atlanta, and although the law on alcoholic prohibition only lasted one year, by that point the name change stuck.

In an interview with Salon, Mark Pendergast notes that although Coca-Cola never contained added cocaine, meaning that the white powder around at the time wasn't added to the drink, but "it did contain fluid extract of coca leaf, which contains cocaine." By 1886, it was available in pharmacies, writes History By Day, sold at 5 cents a glass "as a medicine to improve energy levels and [help] those battling a cold."

While cocaine was clearly a part of the classic Coca-Cola recipe, it wasn't that much cocaine. The original recipe had about 4.3 milligrams of cocaine in a six-ounce drink. By 1903, it was decreased to about 1/400 of a grain per ounce of syrup and by 1929, Coca-Cola no longer contained any cocaine.

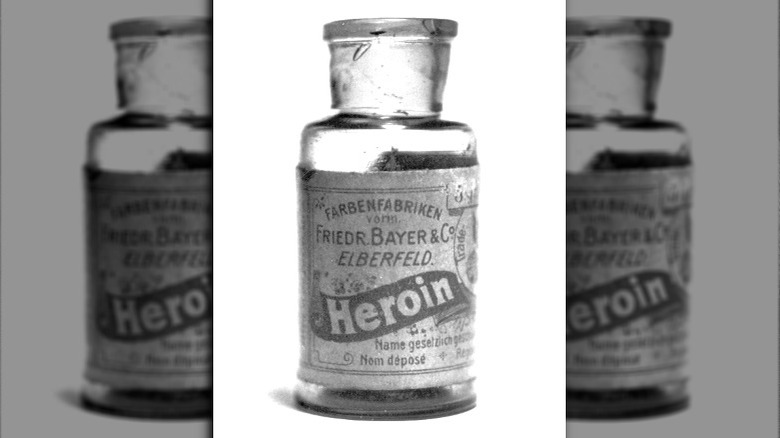

Bayer starts manufacturing heroin

While working for The Bayer Company in Germany in 1895, Heinrich Dreser and Felix Hoffmann synthesized diacetylmorphine out of morphine. Although it would be another three years before heroin, as the new chemical was called, would be commercially available, soon it was being marketed for numerous ailments.

NPR writes that Bayer started marketing heroin as a non-addictive painkiller to be used as an alternative to morphine, but it was also used as a treatment for coughing, pneumonia, and bronchitis in both adults and children. Many of Bayer's advertisements specifically featured children taking heroin. At the same time, Bayer was also coming out with its other famous drug, aspirin. One of their ads read "Aspirin for joint pains. Heroin for coughs," per "Drugs, Crime, and Justice."

According to "A Time-Release History of the Opioid Epidemic," Dr. John Leffingwell Hatch can be assigned some credit for popularizing and legitimizing the use of heroin as a cough suppressant. In several medical journals, Hatch published an article recommending the use of heroin as a cough suppressant, saying that it was effective for all ages, and before long other medical journals were citing his article. Heroin doses would range from 5 to 10 milligrams, but bottles of 5 grams were sold for a time, per History Today.

Morphine syrup for children

Another early medicine for children was Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup, which contained alcohol and morphine. According to the Museum of Health Care at Kingston, it contained approximately 65 mg of morphine per ounce, which meant that a spoonful of syrup was equivalent to about 20 drops of laudanum.

Ultimately, Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup contained such a high dose of morphine in just a single teaspoon that when the American Medical Association published "Nostrums and Quackery," Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup was mentioned in the section "Baby Killers." Although it's impossible to know exactly how many children died from Mrs. Wilslow's Soothing Syrup, since there are no precise statistics, according to the Wellcome Collection, several children in California fell into comas or died from the syrup in the 1860s alone. Overall, it's estimated that thousands of children ended up dying from morphine overdose or withdrawal due to Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup.

Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup had a global market and, despite its notorious reputation, was advertising its product in Australia into the 1920s.

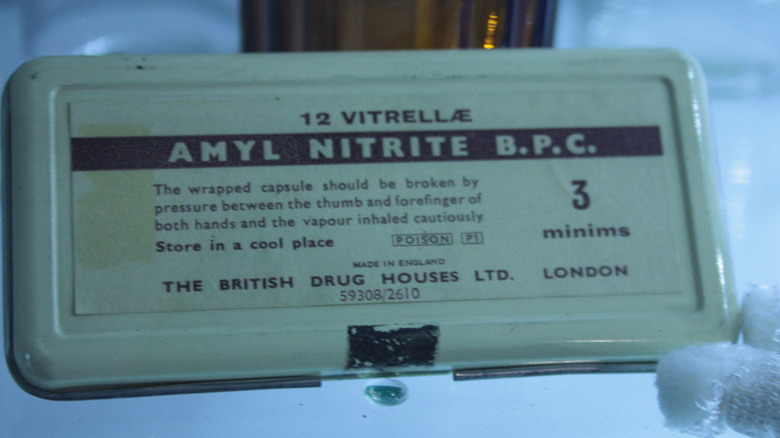

Poppers for your heart

When amyl nitrite was synthesized by French chemist Antoine Jérôme Balard in 1844, he noted down some of the physical effects that came from smelling the chemical's vapor. The effects included feeling lightheaded, now known to be due to a drop in blood pressure, and 20 years after the chemical was synthesized, British physiologist Benjamin Ward Richardson even passed it out to the audience at a medical conference, reports Popular Science.

By the 1900s, amyl nitrite started being used as a vasodilator to treat chest pain caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart. Put into glass capsules wrapped in cloth, also known as "pearls," which were to be broken and inhaled during an angina spell. Because they made a popping sound when crushed, they were also known as "poppers," according to Health Hazards of Nitrite Inhalants. And in addition to chest pains, Vice writes that amyl nitrite was also used to relieve seasickness.

The reign of the green fairy

Nicknamed the Green Fairy, absinthe built up quite the reputation during the Great Binge. Although it was used for medicinal purposes by the ancient Greeks and Romans, by the 19th century it was being used both as an antimalarial as well as its intoxicating pleasures. Made with wormwood, absinth ranged from 90 to 150 proof, according to Artists & Illustrators. However, Mic notes that absinthe never had any hallucinogenic qualities. This myth came out of studies done on animals done by Dr. Valentin Magnan, who set out to prove that absinthe was to blame for the collapse of French culture.

Absinthe soon became associated with artists, but that may have been because it was cheap, not hallucinogenic. After wine vineyards were almost completely destroyed by aphids during the Great French Wine Blight of the 1870s wine became too expensive for the lower classes and absinthe saw "a huge spike in consumption." But that didn't stop the association from forming in people's minds, write Science History. And when Jean Lanfray murdered three people in August 1905 after drinking two shots of absinthe, seven glasses of wine, black coffee with brandy, and another liter of wine in Commugny, Switzerland, it was decided that the absinthe was to blame.

By the early 1900s, both the United States and Europe banned absinthe, despite the fact that one would die of alcohol poisoning before ingesting enough absinthe to induce hallucinations.

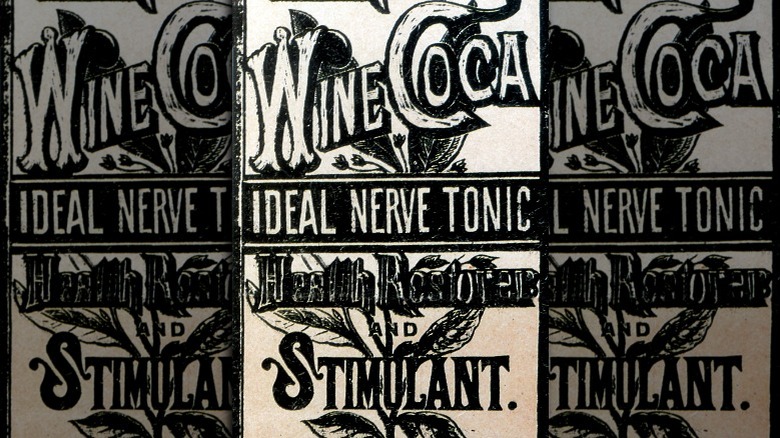

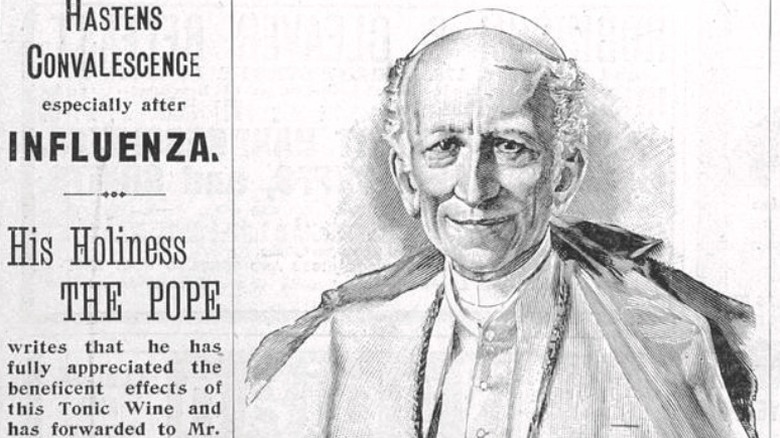

Popes and cocaine wine

In the 1860s, Angelo Mariani created Vin Mariani, a wine that included coca leaves, and it was so well-received that it was praised by not one, but two popes. AV Club writes that originally Vin Mariani contained 6 mg of cocaine per ounce. But after Mariani started exporting to the United States, he had to increase the cocaine in his wine by 20% just to compete with the cocaine wine that was already out on the market in America.

Both Pope Leo XIII and Pope Pius X were known to enjoy Vin Mariani, but Pope Leo loved it so much that he allowed his image to be used in Vin Mariani's advertising. According to Atlas Obscura, Pope Leo even claimed that the cocaine wine strengthened him "when prayer was insufficient." People like Ulysses S. Grant and Jules Verne were also fans of the wine.

And when you realize how much Pope Leo loved his cocaine wine, it suddenly makes sense how he was able to write more encyclicals than any other pope in history, writing 88 out of the 240 that have ever been written, according to History Is Now Magazine.

Drug kits for soldiers

For the first two years of World War I, British soldiers at the front may have received gifts from their loved ones filled with drugs to help make their time there less horrific. According to "A Social History of British Performance Cultures," pharmacies and departmental stores sold little kits with morphine and cocaine, complete with syringes and everything, advertised as being "useful presents for friends at the front."

The morphine was sent to be used as a painkiller and anesthetic, while the cocaine was to help keep the soldiers going. The kit also came complete with syringes. But by 1916, journals were reporting that the drugs were going to make soldiers inept and the Army Council banned the unauthorized sale or supply of drugs to soldiers, writes Łukasz Kamieński in "Shooting Up," including cocaine, codeine, hemp, heroine, morphine, and opium.

Small Wars Journal writes that British soldiers weren't the only ones supplied with cocaine during World War I. Canadian soldiers were also given cocaine in their medicine kits, and German and French pilots were also known to have used cocaine.

The 1912 Hague International Opium Convention

By the start of the first decade of the 20th century, the Great Binge started to wind down with the signing of the 1912 International Opium Convention. The first international drug treaty, the International Opium Convention sought to "suppress opium smoking, to limit its use for medical purposes, to control its exports, and to control its harmful derivatives," according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Signed on January 23, 1912 at The Hague, Netherlands, the International Opium Convention was eventually replaced by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs in 1916, but it established the framework for the international policing of drugs that continues to exist in 2021.

And although this convention only regarded opium and its derivatives, the United States unsuccessfully tried to have cannabis included as well, per UNODC. At the First International Opium Conference, where the Convention was signed, only 12 countries were represented. But by the end of 1912, "all the Powers of Europe" were invited to sign, and the United States was also asked to help get the signatures of Latin American states. But in the end, the Convention was only ratified by China, The Netherlands, the United States, Honduras, and Norway.

The Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914

Two years after signing the International Opium Convention, the United States instituted their own regulation of drug trafficking law known as the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act. Although the Harrison Act didn't ban drugs outright, it taxed opium and cocaine in addition to requiring all manufacturers and distributors to register with the federal government, per the King County Bar Association.

And despite the fact that Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce was limited at the time, since the United States had already signed the Hague Opium Convention, there was an international legal foundation already existing. And Hamilton Wright, who created the Harrison Act, even helped engineer the Hague Opium Convention. According to The Historical Foundations of the Narcotic Drug Control Regime, Wright was essentially the first U.S. drug "tsar," going on to use William Randolph Hearst's newspaper to "generate concern around substance use among minority groups."

Although it was claimed that the act was meant to curb addiction and the medical community initially thought that it would protect them from government interference, since the language of the act was so vague, soon undercover U.S. Treasury agents were arresting thousands of doctors and pharmacists. And almost immediately, anti-drug laws started coming into effect and targeting minority groups, including Chinese, Black, and Mexican people.