The Sad Truth About The Libby Prison Jailbreak

Everybody loves a good prison break story. Indeed, there's a reason why movies like "The Great Escape" and "The Shawshank Redemption" are beloved parts of any film collection decades after their release. There's just something about overcoming incredible odds and risking everything for a taste of freedom that strikes a chord in all of us. Even if the person imprisoned deserved to be there — such as in the case of Frank Morris and the Anglin Brothers, depicted (somewhat fictitiously) in "Escape From Alcatraz" — you can't help but root for them.

However, not every prison break ends in success, and many of the escapees are sent back to face additional punishment for their escape attempts. One of the largest (in scale) prison breaks in U.S. history occurred during the Civil War, and about half of the men managed to reach safety. The other half were either recaptured (and made to suffer for their actions) or died in the attempt.

The Libby Prison was a Civil War POW camp

These days, prisoners of war are, at least theoretically, treated humanely according to regulations set about in international agreements. But that was not the case during the American Civil War. Indeed, history has recorded the inhumane and atrocious conditions at POW camps in places like Andersonville and elsewhere where the prisoners were starved, held in cramped conditions, exposed to the elements, and deprived of medical care.

One such place was the Libby Prison. The Richmond, Virginia building was, at one time, a warehouse, but the Confederate Army converted it to house Union prisoners of war, per Encyclopedia Virginia. Conditions there were, of course, deplorable. However, even worse for the men housed inside, the building was considered to be escape-proof. This was at least partially due to its location in the middle of a city, where any escapees would be plainly visible to townsfolk. Nevertheless, the Confederates' plan to house captured enemy soldiers there had one fatal flaw, and a number of prisoners there exploited it in a bold attempt to escape.

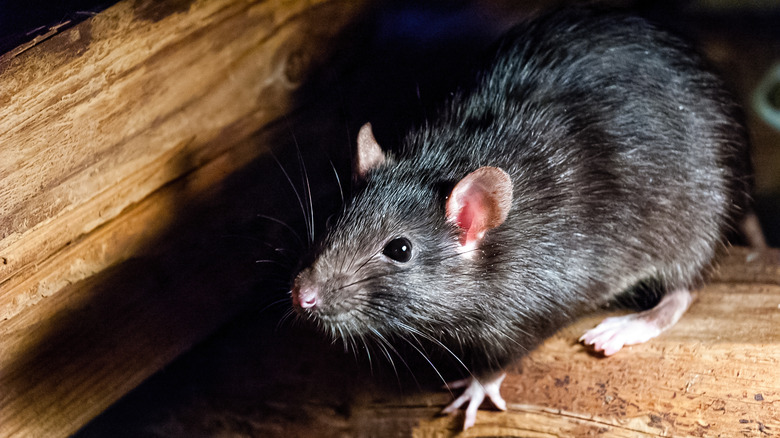

Rat hell

To describe the conditions at Libby Prison as "hellish" goes without saying. But one particular area of the prison had such a bad reputation that even the guards avoided it. According to Discerning History, the building's former kitchen was so infested with rats was that it earned the nickname "rat hell." And Col. Thomas Ellwood Rose and Major A.G. Hamilton, both captured Union officers held in the prison, realized that the former kitchen could be the perfect means of escape, according to Church Hill People's News.

Prisoners used crude tools to chip away at the building's defenses, all while rats crawled over their bodies, and co-conspirators fanned in fresh air to cover the overwhelming putrescence of the place. Over the next 17 days, a handful of tunnels proved not to be useful, but eventually, the men dug a tunnel that opened up on the other side of the fence. Once through, the men could simply walk out into the night and, with any luck, disappear into the countryside.

About half the men who tried to escape were successful

On the night of February 9, 1864, Col. Thomas Ellwood Rose and Major A.G. Hamilton — plus another 107 Union men — crawled through the escape tunnel, past the sentry guards' posts, and walked to freedom on the streets of Richmond. Of those 109, 59 managed to make it all the way back to Union lines to safety, according to Church Hill People's News. Of the remainder, two drowned in the James River, while the rest — including Rose — were recaptured.

Stung by the large-scale breakout from their "escape-proof" prison, as well as a couple of later escape attempts, the Confederates doubled down on the security at Libby. As Encyclopedia Virginia notes, the prison's commandant, Major Thomas Pratt Turner, was authorized to place a bomb in the basement filled with 200 pounds of explosives and threaten to blow up the prison if anyone else escaped. Of course, once the war ended, the building's days as a prison were numbered, and today, nothing remains of the facility save for a single place on the Richmond flood wall.