History Shows These Are The Diseases Most Preventable By Vaccinations

At the time of writing, the global COVID-19 pandemic has claimed 4.5 million lives, infected over 200 million worldwide (per Worldometers), and broken the backs of healthcare systems unable to even provide beds for the sick (per Al Jazeera, the BBC, The New York Times, Texas Tribune, and more). Nevertheless, it's important to remember all the medical advancements that carried us to the present.

Oftentimes, it's said that people live longer now than in the past — that human lifespans have increased. People do indeed live longer, on average, but only because there's less of a chance of dying at an earlier age. The cap for human longevity hasn't increased — immortality may be impossible — and a recent study on Medical Life Sciences reinforces the idea that there's a hard-coded cut-off shelf life for everyone. Quality of life while alive, though, has gone through the roof. Medical science, specifically, is an enormous part of the reason that we actually live in the most prosperous, healthy time in history, as Vox outlines.

A huge chunk of medical advances — up there with surgical procedures, diagnostic tools, and disease therapy — is disease prevention and antibiotics. From the implementation of penicillin in the early 1940s (per American Chemistry Society) to the future of nanotechnology to treat individual cells (per Technology.org), progress in medicine has come a long, long way in only the last 100 years. Vaccines, in particular, have given us a foothold against diseases that once swept through humanity unchecked.

Vaccines have eliminated 99% of polio cases the world over

Paul Alexander, a lawyer in Dallas, Texas, is a survivor of polio. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, through the early 1950s, this disease left 35,000 children per year crippled, mangled, wheelchair-bound, and in extreme cases, paralyzed. Alexander, who did an interview with Gizmodo on YouTube in 2017, lives inside an iron lung, which is a pressurized machine of metal and glass that forces his lungs to inhale and expel air. Only his head is exposed and he lays on a towel all day. He contracted polio in 1952 at the age of six and remains paralyzed from the neck down. And yet despite polio having such a horrifying history, as Alexander accurately says, "A lot of humanity knows nothing about polio. They don't even know what it is."

In the United States, new polio cases were 100% eliminated by 1979. Like any disease preventable using vaccines, though, polio is still with us — it's just held at bay. As the World Health Organization says, worldwide cases of poliomyelitis (its full name) have decreased by 99% since 1988, shrinking from 350,000 total cases to a mere 22 by 2017. Only two countries in the world, Pakistan and Afghanistan, have never inoculated against it, leaving five out of six WHO regions — Africa, the Americas, Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific — "wild poliovirus free," as the CDC says. Without a vaccine, polio would have left 18 million people paralyzed.

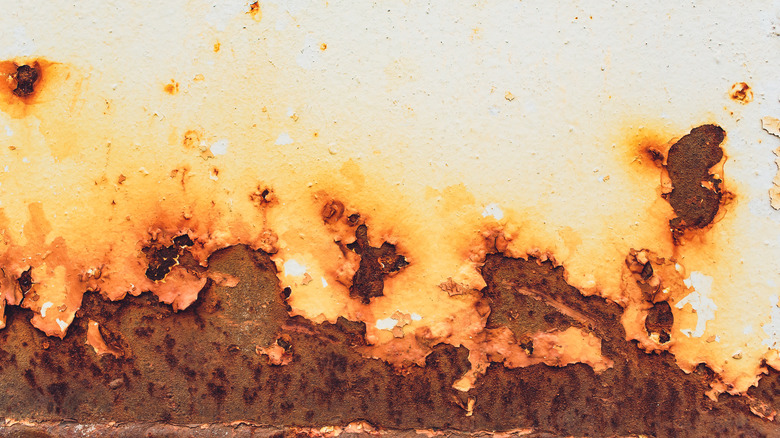

Tetanus can cause lockjaw and is preventable through booster shots

Folks who grew up in the 1980s or earlier (or maybe later, too) might recall their parents rushing over them if they got a cut, scouring for nearby patches of rusted metal, and muttering something like, "Okay, okay, you got your tetanus shot ... what, six months ago? You're good." Tetanus — a bacterial disease that causes lockjaw, painful spasms, fever, and rapid heartbeat — comes from bacteria that can live a long time outside of a host and enter the body through lesions, per the National Health Service. Cuts, gashes, piercings, animal bites, or things that generally tear the skin and leave inner flesh exposed — the deeper the wound, the greater the danger.

Tetanus is completely preventable through vaccines commonly given to children in groups along with vaccines against diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough), as the CDC outlines. Each country has a slightly different vaccination schedule spread out over childhood, which adjusts with age and concurrent changes in the immune system. As an adult, folks can get tetanus booster shots, especially if they suspect they might need protection against lesions or abrasions (on a long hiking or camping trip, for instance). If it's been more than 10 years since your last booster, it might be time to make an appointment, per WebMD. Lockjaw, the most serious symptom of tetanus, has no cure and kills 10-20% of those who develop it.

Diphtheria was once the third most common cause of death in England and Wales

In 1659, a Boston minister named Cotton Mather wrote about a "malady of bladders in the windpipe" that "invaded and removed many children; by opening of one of them the malady and remedy (too late for very many) were discovered." As quoted by the History of Vaccines, he continued, "The Lord sent a general visitation of Children by coughs & colds, of which my 3 children Sarah, Mary & Elisabeth Danforth died, all of them with[in] the space of a fortnight." Per NHS, Mather was correct in describing diphtheria as "bladders in the windpipe," because it typically manifests as "a thick grey-white coating at the back of your throat," which causes difficulty breathing. It also creates sores on the body, including "pus-filled blisters" and "large ulcers surrounded by red, sore-looking skin."

As the History of Vaccines states, diphtheria peaked in the United States in 1921 with 206,000 recorded cases resulting in 15,520 deaths. In the 1930s it was the third most common cause of death in England and Wales. Following World War II, diphtheria vaccinations thankfully went on the uptick, by 1950 reducing the total number of cases to a mere 962, the U.S. National Library of Medicine reports. Even though diphtheria still affects people in less vaccinated areas around the world, in the U.S. it was all but completely eliminated by 2004, with one case reported in 2012.

Whooping cough is making a comeback and shouldn't be taken lightly

Whooping cough (pertussis by its formal name) is another disease that's become far less threatening thanks to vaccinations but hasn't totally vanished. Before its vaccine was developed, treatment methods included placing children in specially pressurized rooms to reduce their symptoms (pictured above). This is because whooping cough causes a sudden increase in blood pressure. As reported by Rare Diseases, this spike can cause nosebleeds, ruptured blood vessels in the eyes, collapsed lungs, inflammation of bronchial lubes, hernias in the groin, inflammation of the brain, and more. And of course, there's the key symptom: a "paroxysm" of uncontrollable, spastic coughs that eventually produce a huge "whoop" sound – hence the name. And as is often the case, children — especially babies — are the most susceptible.

Before the vaccine became available in the 1940s, there were about 200,000 cases of whooping cough per year resulting in approximately 9,000 deaths, the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases reports. Whooping cough is a particularly volatile and transmissible disease, though, and hasn't been completely eliminated. In fact, it's been on the comeback, with 48,277 cases reported in the U.S. in 2012, despite reaching an all-time low of 4,000 cases in the 1980s, per Smithsonian. This definitely emphasizes the need for vigilance regarding childhood vaccines and booster shots as adults. For children, the whooping cough vaccine is often given in conjunction with other vaccines, such as those for tetanus and diphtheria.

Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines are combined into a single shot

Measles is a human-only disease transmitted by air that settles in the lungs and works through the body from there. As the WHO tells us, its well-known rash symptom is only the first sign of the disease. Severe diarrhea and dehydration, respiratory infections such as pneumonia, even blindness and swelling of the brain — all of this and more can debilitate an adult and outright kill the young.

Before the measles vaccine was developed in 1963, epidemics of measles broke out every 2-3 years and left a staggering 2.6 million dead around the world each year. Since then, instances of the disease have dropped dramatically, but because it was always so rampant, there were still 140,000 cases worldwide in 2018. That being said, it's estimated that from 2000-2018 alone, the vaccine prevented an astounded 23.2 million deaths.

The vaccine for measles has only gotten better over time. The measles-mumps-rubella (MMR in the U.S.) vaccine is possibly one of the most well-known triads of combined vaccines the world over. When administered properly in two doses, the vaccine is 97% effective against measles and rubella, and 88% effective against mumps, per CDC data. As the NHS states, those born between 1970 and 1979 might have only been vaccinated against measles, and those born from 1980-1989 against muscles and rubella, but not mumps. It's important for those born during these time periods to make sure that they're fully protected.

Hib has shrunk to 0.18 cases per 100,000 people

Hib — or Haemophilus influenzae type b — is a disease all but forgotten despite its relatively late development as a vaccine compared to others in this article. As WebMD outlines, Hib is terrifyingly destructive, largely because it causes bacterial meningitis: the transfer of bacteria to the meninges, a covering surrounding the brain and spinal cord that is typically bacteria-free. The disease has a 3-6% fatality rate, and those it doesn't kill face intellectual disabilities, comas, blindness, paralysis, pneumonia, bone disease, premature arthritis, hearing loss, seizures, and more. It's spread in droplets through coughing or sneezing and is particularly deadly for children under five.

Prior to the implementation of the vaccine in 1992, there were about 20,000 cases of Hib per year. Since then, the number has drastically dropped. The NHS reports no more than 10 cases in the entirety of the United Kingdom in 2018, or 0.18 cases per 100,000 people in the U.S., according to the CDC. Like other diseases on this list, certain populations are at risk besides young children: Native Americans, the elderly, those with pre-existing conditions like sickle cell anemia or HIV, or those who've passed through radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or stem cell transplants.

The Hepatitis B vaccine is 90% effective but has a low vaccination rate

Hepatitis B (HBV), or "Hep B," as it's commonly called, is a disease that carries with it a stigma due to transmission methods associated with lifestyle choices: bodily fluids such as semen or blood, shared needles, sore-to-sore contact on the mouth, and more. According to the CDC, HBV causes the development of two sets of symptoms: one short-term and the other long-term. The short-term symptoms include nausea, vomiting, fever, and fatigue, while the long-term symptoms transform Hepatitis B into a chronic, lifelong illness that never goes away but also isn't lethal. Healthcare workers often have to mandatorily get the HBV vaccine because they might come into contact with infected blood and "sharps" (needles, etc.) on the job.

Perhaps because HBV is more often transmitted between adults, it has a lower vaccination rate than those typically administered to children. As the CDC says, by 2017, only 25.8% of people aged 19 or older in the U.S. had received the full three doses of the vaccine. Per the NHS, this is in spite of its 90% effectiveness in developing protection. Due to the low vaccination rate and the virus' transmission methods, there are approximately 257 million people worldwide currently living with HBV. Infection is particularly rampant in areas of Southeast Asia, China, parts of the Middle East, most Pacific Islands, most of Africa, and the Amazon Basin, where as many of 8-15% of the population is infected.

A worldwide smallpox campaign obliterated a 3,000-year old disease

Even though there are plenty of other diseases preventable through vaccination, diseases like typhoid fever don't pose an imminent threat unless traveling to an area of the world where it's still alive, such as India or Pakistan, per the CDC. Other vaccines such as the anthrax preparation aren't available to the general public, also per the CDC.

It makes sense to end on the ultimate vaccination success story: smallpox. Smallpox has a mindbogglingly long and notorious history spanning back to 1000 B.C.E. in Ancient Egypt — blemishes from its skin-mottling pustules can be found on mummies, as the CDC says. By the 6th century, smallpox appeared in Japan through China and Korea and took centuries to travel to the Middle East, where it was passed around because of the Crusades in the 11th century. The virus then made its way to Africa through Portugal in the 12th century, and eventually out to the Americas and Australia. In 1959, the WHO declared its campaign to eradicate smallpox once and for all, but poor funding hampered the effort until 1967's Intensified Eradication Program. Work on the vaccine started as early as 1796 by the English doctor Edward Jenner, who in 1801 published "On the Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation."

One of the final patients to develop smallpox in the history of the world was 3-year-old Rahima Banu from Bangladesh in 1975. The last person to die from it was Janet Parker in England in 1978.