The Mythology Of Demeter Explained

The ancient Greeks had some seriously important reasons to stay on the good side of all their gods: Offend Artemis, for example, and you just might find yourself turned into a stag and torn apart by your own faithful dogs.

Fun times. Hey, at least they all get points for creative vengeance.

As the sister of Zeus, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Hestia, Demeter was one of the older Olympians — and she was incredibly popular, because the last goddess you wanted to upset was one that could destroy the world with famine. Demeter was the goddess of agriculture, and Theoi says she was specifically associated with grain and, by extension, bread.

It was Demeter who gave humankind the ability to farm, grow, and in turn, develop civilization. Her messenger was Triptolemos, a prince turned demi-god who earned her favor when he gave the goddess shelter as she wandered the land in search of her missing daughter. She granted Triptolemos a chariot drawn by snakes, which he used to spread the gift of agriculture. When Lynkos, king of the Scythians, tried to kill Triptolemos, Demeter turned him into a lynx.

So... maybe be sure to give this goddess the respect she deserves.

Demeter had a rough start to life

Demeter — whose name means "giver of barley" — was one of the first generation of Olympians. The daughter of the Titans Rhea (goddess of motherhood, generations, and the progression of time) and Cronos (god of time), Demeter was originally swallowed by her father just after she was born. Cronos had been told of a prophecy that one of his children would take his place at the top of the pantheon, and one did: Zeus, who was hidden away by Rhea until he was old enough to return and — with the help of the Metis — give the Titan with a potion that made him throw up his children, who then banished him to a place deep beneath the earth.

After the siblings were vomited up by their father, Zeus ended up marrying his sister Hera. In the meantime, though, he still found time to have a daughter with Demeter. That was Persephone — and there's a lot more to her story.

Persephone is the most famous of Demeter's children, but she's not the only one. There are a few more agricultural gods — like Ploutos and Eubouleus — and an immortal horse named Areion. Mount Olympus was a weird place.

The story of a mother and daughter

Demeter is a little unique among the gods in that she doesn't really appear in many stories. She doesn't have an active role in famous works like "The Odyssey," and she's not in any of the surviving Greek dramas. She is, however, at the center of a massively important story involving her daughter, Persephone.

According to La Trobe University's professor of Classics Chris Mackle (via The Conversation), it's told in a 6th century BC Homeric hymn. Things kick off when Hades, god of the underworld, sees Demeter's beloved daughter picking flowers. He's a Greek god, so of course he kidnaps his sister's daughter and spirits her away to his domain.

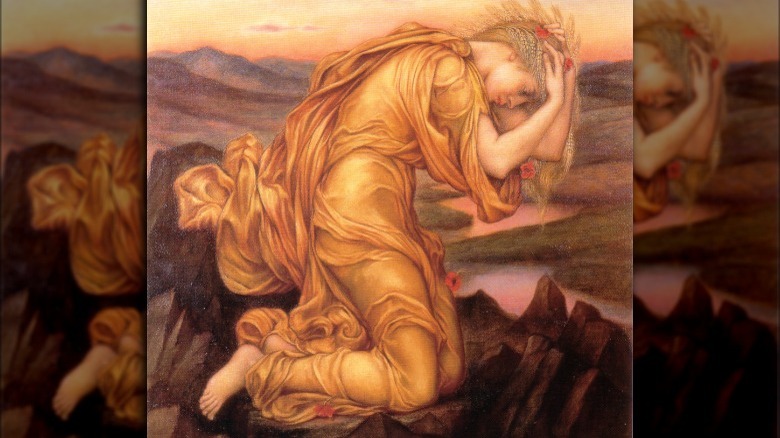

Demeter abandons her duties to mankind and starts searching for her daughter. She wanders for nine days, asking her fellow gods if they have seen any trace of her daughter. Crops begin to die, famine sets in, and she makes it clear that she's not going to let anything grow until Persephone is returned. According to the hymn (via Theoi), she finally discovers the truth from Helios (the Sun), then sinks into a deep depression. Disguising herself as a mortal, Demeter wanders from city to city and ultimately either curses or rewards those she meets.

Zeus intervenes, but Persephone has done something small but life-changing: she has eaten a pomegranate seed. This action is enough that Hades can insist she spend a third of the year with him, and two-thirds with her mother.

The story of Demeter and her daughter has far-reaching consequences

Persephone's stay in the underworld and annual return to her mother is one of the events that helped to shape the world as the ancient Greeks knew it, says La Trobe University's professor of Classics Chris Mackle (via The Conversation).

There are a few things going on here. For starters, Persephone's journey is reflected in the seasons. When she leaves her mother for the underworld, Demeter mourns. The land grows barren and cold, plants wither and die, and the life cycle comes to an end.

But Persephone also represents hope. Theoi says she's usually depicted in art as a young girl holding a torch and stalks of grain, whether she's pictured with her mother or her husband. Her return to Demeter and the world above brought life back to the land, as spring returned with her. Winter happens when she steps into her role as queen of the underworld, but as the goddess of spring, she and her mother give life, as well.

The presence of Persephone in the underworld also served to make it a little less of a scary place. It gave people the sense that they were a part of a cycle, and at the heart of that cycle was one of the most powerful forces in the world: a mother's love for her daughter.

Many stories about Demeter involve her search for Persephone

Unlike other gods, who spend a good amount of their time messing up the lives of humans, many of Demeter's stories happen in the relatively short time she's wandering the land looking for her daughter. She came across a large number of people as she searched, and how they received her pretty much sealed their fate.

Not only did all of mankind pay with a great famine, but she also singled out some particularly offensive people. Askalabos came across the famished goddess as she was pausing for a meal, and when he mocked her ravenous appetite, she turned him into a gecko. Then, there were the Seirenes. While they were Persephone's handmaidens, they refused to help Demeter in her search, and were turned into monsters as a result.

But Demeter was also very grateful to those who welcomed her into their homes or helped her on her journey. She gave Phytalos the first fig tree for his kindness, and gave the Eleusinian king Keleos the gift of farming and agriculture (via Theoi). Trisaules and Damithales gave her shelter, and were rewarded with the gift of a crop called pulse, while the prince Triptolemos was made a god of sowing and milling.

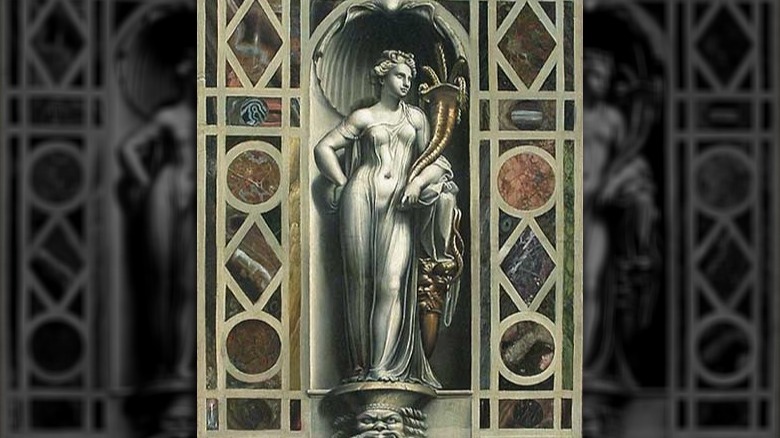

Demeter had some strange sacred symbols

Demeter's chariot wasn't drawn by regular horses. Instead, she used a set of winged serpents called Drakones to not only pull her chariot, but to serve as her personal guards as well. Serpents were one of her sacred animals, too: they were thought to represent fertility and rebirth.

Most of the Greek gods had symbols and attributes, and Demeter was no different. When she showed up in ancient art, she was usually identifiable by the torches she held, in a reference to her desperate search for her daughter. Theoi says she was sometimes depicted as holding a sword or a sickle, and that it was no ordinary scythe.

The world began with Ouranos and Gaia, who were (respectively) the sky and the Earth. When Ouranos insisted on locking their eldest children away inside the Earth, the pain was so great that Gaia encouraged her Titan sons to rebel. That included Cronos, who put an end to things when he castrated his father with a scythe.

Ouranos cursed his son to be dethroned by his own offspring — just as he had been — and the prophecy came true. Meanwhile, the scythe was found by Demeter, and was used to harvest the first grain crop ever grown.

Demeter and the creation of mint

Demeter was heartbroken when Hades stole her daughter away, and while it might seem like she would have appreciated any help in getting Persephone back from the underworld, it turns out that whole "enemy of my enemy is my friend" thing doesn't really work for Greek gods.

Hades had his share of lovers before Persephone, and one of those was the nymph Minthe. According to the Greek writer Oppian (via Theoi), Minthe was pretty bitter when she was replaced by Demeter's daughter. She was just as vocal about it, too, complaining that she was "nobler of form and more excellent in beauty," while making it clear that she was all about kicking Persephone out and taking back what she viewed as her rightful place.

Demeter may have wanted her daughter back, but she wasn't about to stand for that disrespect, either. There are two versions of what happened. One says that she turned the nymph into dust, and Hades sprouted the mint plant from Minthe's remains. The other says Demeter turned Minthe into mint, and there's a little footnote to this, too. Anyone wondering what mint has to do with Hades and the underworld might look at the plant differently once they know that the fragrant leaves were (likely) used during ancient funerals to help cover the smell of the dead.

Demeter, her mortal love, and the constellations

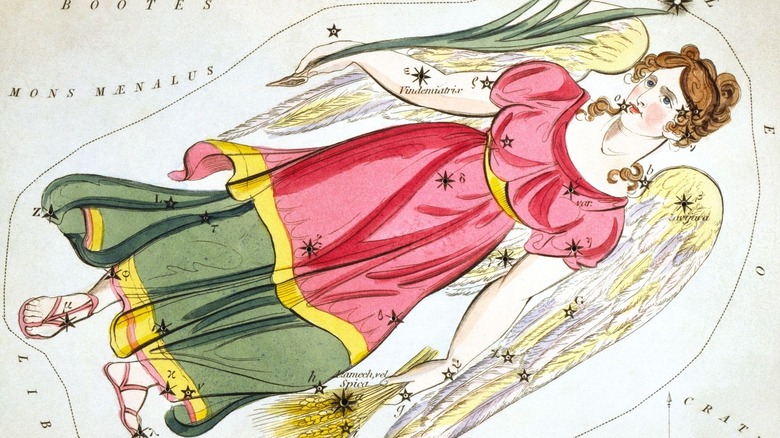

According to World History, Athenians had a bunch of different calendars, and the parapegma — which was used to tell people when they needed to plant crops and plan for the harvest — was based on the cycles of the moon, sun, and constellations. Knowing that, it's not entirely surprising that Demeter became associated with several major constellations.

Virgo reappears in the sky in late April, according to EarthSky, and is said to represent the reappearance of Persephone alongside the return of the spring. Virgo then starts to sink below the horizon in late August or early September, heralding Persephone's return to the underworld and the slow dying of the summer.

Gemini is also connected with Demeter. According to the Pseudo-Hyginus, the two figures are men beloved by Demeter. One is Triptolemos, the grain-bearing prince of Eleusis, and the other is Iasion, Demeter's springtime lover. Sometimes a mortal and sometimes the son of Zeus, he and Demeter fell in love, but when Zeus killed him with a thunderbolt for his insolence, Demeter raised him to the stars as half of the constellation.

The constellation Bootes is said to be Philomelus, the son of Iasion and Demeter, and inventor of the plow.

Becoming a constellation is not always an honor, though. Ophiuchus is said to be a king of the Getae who killed one of the serpents that drew the chariot of Triptolemos. As punishment, Demeter condemned him to a life in the stars, where he forever holds a serpent.

Demeter the law-giver

Different areas of the ancient world gave Demeter different titles. Sometimes she was called the Bringer of Sheaves in reference to her gift of wheat, and she was also called Of the Furrow, Fruit Bearer, or The Green Shoot. In places including Athens, Pheneos, and Megara, she was known as Demeter The'smia, or Thesmo'phoros, which essentially translates to Demeter the Law-Giver, because in addition to giving mankind the gift of agriculture, she also provided law. (Sometimes, says Theoi, Persephone was given those same titles, and they were called The Two Goddesses.)

It seems like an odd combination at first glance, but according to Greek religion scholar Allaire B. Stallsmith's "The Name of Demeter Thesmophoros," it actually makes a lot of sense.

"Law" is meant in a few respects. First, Demeter revealed the laws that governed her secret rites and rituals, but she was also said to have established the natural laws that govern the way things grow and the cycle of life.

Then, writers including Callimachus say that she also gave mankind the idea of civil laws and ordinances (via Theoi). As Mythagora points out, the gift of agriculture allowed mankind to settle into cities and towns, and in order to make the most of her gifts, they needed to figure out how to live in close-knit societies and work together to plow fields, sow seeds, harvest crops, and process — then share — the fruits of their labors. Fortunately, she's credited as showing them how.

The extreme secrecy about the inner workings of worshipping Demeter

Demeter was one of the most widely celebrated and most important goddesses in the Greek pantheon, but here's where things get weird. Oxford Classical Dictionary says that the heart of her worship was in the city of Eleusis, just outside of Athens. This was also the location of a yearly festival, and while the public events were well documented, no one has the foggiest idea what went on behind the closed doors of the inner ritual.

Why? In spite of the fact that over the years, thousands upon thousands of people would have participated, no one ever revealed what happened. The punishment for doing so was death, and Roman historian Livy wrote that authorities followed through with it in the execution of at least two foreigners who accidentally stumbled into the ceremony (via Oxford Classical Dictionary).

The chief archaeologist of Eleusis, Kalliope Papangeli, says that at the height of the festivities, 3,000 people — women, men, slaves, land-owners, and children — were invited in as initiates (via The New York Times). The only requirements were no murderers, and the ability to speak Greek. The sheer number of people who participated makes it wildly impressive that no one ever spilled the beans.

There was more to it than just the threat of execution, though. The ritual — along with Demeter and Persephone — gave people hope that the afterlife wasn't going to be that bad after all, and that's the kind of thing no one wants to mess with.

The Eleusinian Mysteries

So, what do we know about the Eleusinian Mysteries, that mystical, mysterious festival dedicated to Demeter and her beloved daughter?

Kalliope Papangeli, head archaeologist at Eleusis, says that the most sacred part of the ritual would have started with initiates partaking in the drink called kykeon (via The New York Times). While it's often repeated (via Gizmodo) that it was a psychedelic drink, Papangeli says that probably wasn't the case at all. They were simply drinking a mix of mint, barley, and water — the same meal that Eleusinian queen Metaneira gave Demeter as she rested in her search (via Oxford Classical Dictionary).

As participants walked through the sanctuary and ultimately down into the caves beneath, they would have seen actors and priests reenacting the abduction of Persephone by her uncle, Hades. Persephone would return to the surface — with the initiates — and everyone would move into a massive space called the Telesterion.

And that's where the mystery starts.

There are a few clues as to what went on in that innermost ritual, including three words: dromena, deiknumena, and legomena. That's pretty vague, as it translates to "Things done, things shown, things said." The New York Times explains that a further hint was buried in a later, Gnostic text, which referred to "the ear of wheat harvested in silence." What the heck does that mean? No one's sure, exactly, but it's almost definitely a reference to Demeter's ultimate gifts: wheat, grain, bread, and life.

A brutal assault and the birth of another mystery cult

The great goddess of the harvest wasn't at the heart of just one major mystery cult, but two.

During her quest to find her daughter and bring her home, Pausanias wrote that the grieving Demeter caught the lustful eye of her other brother, Poseidon (via Theoi). In an attempt to get away from him, Demeter turned herself into a mare and joined a herd of horses in Arkadia. Poseidon wasn't about to be deterred — he turned himself into a stallion, and had his way with her.

The union bore two children: the immortal horse Areion and a daughter named Despoine. Despoine became sacred to the Arkadians, as did the cave where Demeter supposedly retreated after being assaulted.

Another mystery cult sprang up around Despoine (or Despoena), and while the details are fuzzy, what we do know is weird. Only initiates into the cult — which also honored Demeter, Persephone, and Artemis — were privy to the details, but Pausanias wrote that the sanctuary included a statue of a horse-headed woman, and a mirror that would reflect only shadows of anyone who looked into it, but that would clearly show the reflection of the gods. There were also sacrifices — a lot of sacrifices — and victims were killed by cutting off a limb.

The end of Demeter's cult

It's impossible to exaggerate just how important Demeter, her cult, and the Eleusinian Mysteries were. World History says that the first of these rituals were held sometime around 1600 B.C., and for a long time, the only actual road in the Greek world was the one that spanned the 14 miles from Athens to Eleusis, where Demeter had rested beside a well on her journey to find her daughter. It was there, too, that she — in disguise — cared for the city's young prince. When his mother found the old woman baptizing her son in fire she was understandably upset, but when Demeter revealed herself, it was agreed they would build her temple, and the prince would grow up to be the demigod and bringer of grain, Triptolemos.

The road was the Sacred Way, and it was meant to trace the same path Demeter took on her journey.

Those who participated in the Eleusinian Mysteries were said to be forever changed: Plato wrote "because of those sacred and faithful promises given in the mysteries... we hold it firmly for an undoubted truth that our soul is incorruptible and immortal."

It's not entirely surprising, then, that Christianity had a huge problem with Demeter. The rituals officially came to an end in 392, when Emperor Theodosius decreed the entire thing was an affront to Christ and the one true religion of Christianity. Demeter's temple was abandoned, and completely destroyed by the Christian Alaric, King of the Goths, in 396.