Messed Up Things That Happened During The Reformation

If you could travel back in time to witness groundbreaking historical events, where would you go? Maybe you'd spend time hanging out with the Wyatt brothers in the Wild West? Or head to 1920s Paris to rub elbows with Pablo Picasso, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway?

Some might rocket their way back to witness the birth of Jesus of Nazareth or jump to post-World War II India to gain words of wisdom from Mahatma Gandhi. Most of us likely wouldn't want to head into a time of rampant religious warfare, witch trials, or massacres that could happen at the drop of a dime. And even fewer of us would likely want to live in a place where religious affiliation could result in getting burned at the stake (via Royal Museums Greenwich).

In other words, should the DeLorean ever show up, make a mental note to avoid 16th century Europe and North America. Why? Because without putting too fine a point on it, lots of messed up things happened during the Reformation.

A man's word meant nothing

Most people associate the Reformation with Martin Luther, but a century before he spoke at the Diet of Worms, the reformer Jan Hus rocked Christendom. A Czech university professor, Hus launched the Bohemian Reformation based on the British academic theologian, John Wycliffe's teachings. According to Grace and Truth, Hus' popularity increased immensely over time. By 1402, he pastored one of the largest churches in Europe, the Priest of Bethlehem Chapel in Prague.

He taught against practices that exploited the peasantry, such as the sale of indulgences (forgiveness for sin). As reported by Musée Protestant, "he was as concerned about social justice as religious morality." Nevertheless, he learned the hard way that a person's word meant nothing, even those of seemingly pious religious leaders. According to Britannica, the controversial, excommunicated reformer received an offer of safe conduct to the Council of Constance in 1415. There, he and other religious figures would deal with a papal schism and discuss his reformed teachings as well as those of Wycliffe (via Reformation 500).

Despite these documented promises of protection from Emperor Sigismund, Hus found himself on trial as a heretic. He was imprisoned, and then burned at the stake. But Hus' persecutors weren't finished. They picked through the remains of the pyre to gather Hus' ashes, dumping them into the lake. In other words, he was denied burial in consecrated ground.

Crusades could be launched anywhere

Most people associate the word "crusade" with the Christian attempt to take Jerusalem from the Muslims. But papal crusades could get launched against anyone who disagreed with the church's religious leaders, according to Britannica. After Hus' death, the Hussites of Bohemia refused to elect a Catholic monarch. As a result, they found themselves on the radar of the Vatican. The result? They became the target of five papal crusades between 1420 and 1431.

Enraged by the execution of their beloved leader, the burning of his books, and his improper burial, the Hussites (as they became called) easily repelled the Catholic forces. According to Musée Protestant, they also threw prominent Catholic leaders out of windows, killing them. Relying on new military technology, including hand-held firearms such as wagon forts and hand cannons, Hussite soldiers kept the region in chaos for decades.

An internal storm brewed between moderate Hussites (Ultraquists) and more extreme sects of the reformed faith, including the Taborites. As the extremist threat within the Hussite factions continued to grow, moderate members of the Ultraquist faction eventually allied with the Roman Catholics. In exchange for helping to snuff out the "craziest" members of their brood, the moderates were allowed to practice their "religious variant" unimpeded.

Entire populations faced forced conversion

Despite repelling five crusades in twice as many years, the Hussites learned firsthand that it only took one defeat to usher in compulsory conversion (via Warfare History Network). The Thirty Years War began with the Battle of the White Mountain, and the stakes were high. Protestant Bohemians faced off against Southern European Catholics for control of Bohemia.

The battle would last for just two hours, yet it would result in a "crushing defeat" for the Protestants (via The World of the Habsburgs). In the aftermath, 27 Protestant leaders were executed, and "the Bohemian Estates [were] deprived of power." What's more, they experienced hundreds of years of authoritarian rule, involving an intense forced return to Catholicism, the execution of their leaders, and total loss of political power, according to Marie-Elizabeth Ducreux's review of "Converting Bohemia: Force and Persuasion in the Catholic Reformation."

The recatholicization of Bohemia left many feeling disenchanted by the intense focus on orthopraxy (right doing) over orthodoxy (right beliefs). Nevertheless, the region would endure centuries of repression.

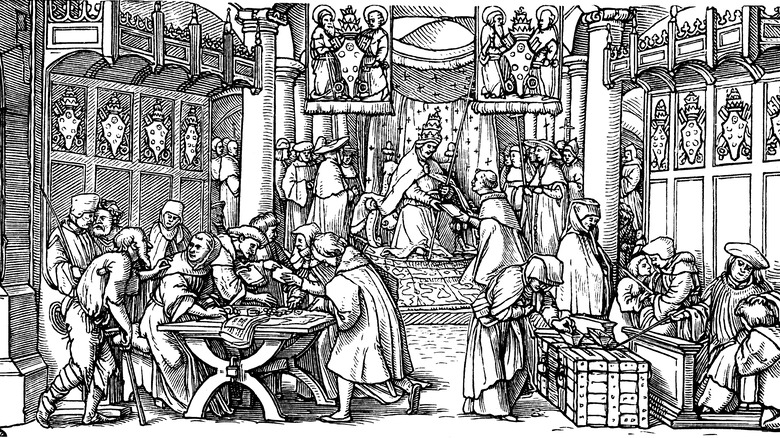

The church peddled forgiveness to fat cat sinners

Corruption ran rampant in the Roman Catholic Church before the Reformation. Not only did church leaders go to great extremes to keep Bible learning out of the hands of laypeople, but they also wielded incredible power over life and death, heaven and hell. Through the seven sacraments, the church managed to control nearly every aspect of life. According to St. Anthony of Padua, these sacraments were Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Reconciliation, Anointing of the sick, Matrimony, and Holy Orders.

Yet, the sale of indulgences (or forgiveness for sins) represented the straw that would break the camel's back (via ThoughtCo). In other words, no matter how despicable the human being, money talked when it came to a passport to heaven. (Well, at least that's what the church said.) ThoughtCo explains: "Buy an indulgence for a loved one, and they would go to heaven and not burn in hell. Buy an indulgence for yourself, and you needn't worry about that pesky affair you'd been having."

Interestingly, in 2009, the New York Times reported that the Catholic church had returned to dispensing indulgences. How much does it cost to sweep things like idolatry and murder under the rug today? Instead of charging money for these dispensations, the church requires specific pilgrimages, devotions, and prayers.

Religious tolerance proved non-existent

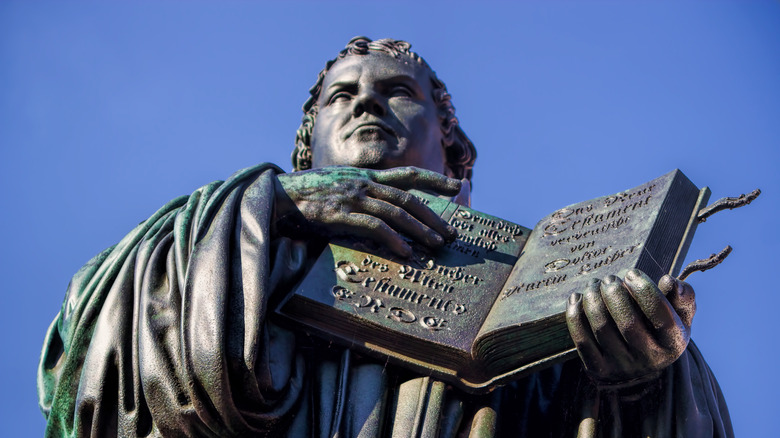

In 1517, Martin Luther famously nailed his "95 Theses" on the church's doors in Wittenberg, touching off the Protestant Reformation, per Lutheran Reformation. Why did he put his neck out despite the apparent danger illustrated by his predecessor Jan Hus? Because of the disgust he felt when church officials attempted to part the German peasantry from their hard-earned and scarce savings.

When Martin Luther came out against the corruption within the church, he faced ex-communication and the distinct possibility of a fiery death at the stake. Getting summoned to the Diet of Worms in 1521 seemed to seal the deal. Yet, Luther courageously appeared before the council, prepared for whatever punishment accompanied his religious convictions. He remained defiant throughout the proceedings, famously concluding his speech, "Here I stand; I can do no other. God help me. Amen!" (via Quote Park).

Although he received protection from the local German noble Frederick the Wise, Luther still faced exile. He withdrew to Wartburg Castle, going by the name of Junker Jörg and growing out his beard and hair. During this time, he devoted himself to translating portions of the Bible.

Holy Wars and bloodshed rocked the continent

The Protestant Reformation and the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation led to more than a century of vicious warfare among the European political powers of the day. The result? Europe remains divided among geographical and religious lines from north to south. According to Rick Steve's Classroom Europe, while there was a strong focus on religion in these conflicts, they devolved into land and power grabs.

Religious-inspired chaos and conflict culminated in the Thirty Years' War, taking place from 1618 through 1648. Although many nations got involved in the war, the German regions would bear the brunt of the violence, seeing a third of the population perish. According to Rick Steves, "After literally millions of deaths, the devastation of entire regions, and wide-spread economic ruin, all involved were exhausted."

Did the end of the war bring religious tolerance? Not on an individual level. But leaders of each nation gained the power to choose the faith of the area they ruled. Latin Christendom fractured into two camps that more or less exist today: Protestantism in northern and western Europe and Catholicism in southern Europe.

Peasants got betrayed and murdered

In 1525, peasants rebelled against the ruling order in Germany to overthrow the elite, according to Leverhulme Trust. Their inspiration? The words of Martin Luther. Hundreds of thousands of peasants united to violently overthrow the government during the German Peasants' War from 1524 to 1525. But it didn't turn out well. Luther thoroughly condemned the peasants and even advocated for their deaths, leading to unprecedented bloodshed.

How did a misunderstanding of this tragic magnitude take place? At least partially because of Luther's mixed interests, as reported by ThoughtCo. He had long identified with the salt-of-the-earth peasants. He demonstrated some of this sympathy in his 1525 work, "Admonition for Peace," in which he mocked the "arrogant" attitude of the aristocracy. Nevertheless, after the Diet of Worms, he couldn't deny that the only person genuinely protecting him was a nobleman, Frederick the Wise.

When peasants started to attack and even kill local nobility, Luther found himself stuck between a rock and a hard spot. Peasants had applied Luther's arguments about individual liberty and conscience to the political sphere and the religious one. Would he bite the hand that fed him to ally with the peasantry? Or would he acknowledge his debt owed to Frederick the Wise? As the "misapplication" of Luther's writings contributed to increasing anarchy, Luther went much further than merely distancing himself from the rebels. He wrote, "They must be sliced, choked, stabbed, secretly and publicly, by those who can, like one must kill a rabid dog" (via Dokumentar Film).

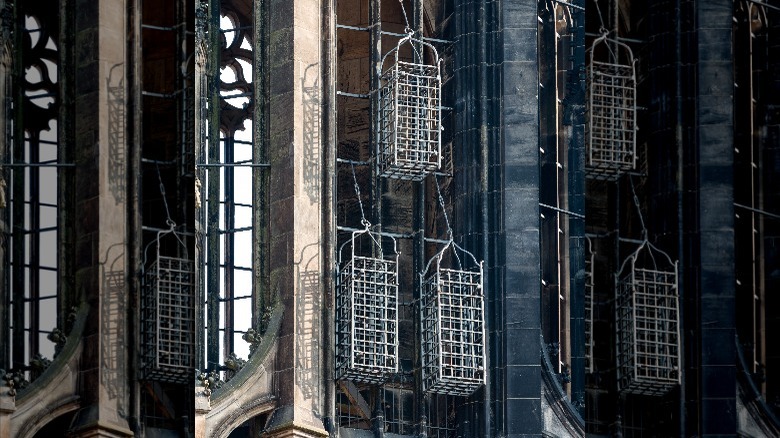

Religious extremists received nasty punishments

In the city of Munster, a group of Anabaptists went wild in 1534, seizing the civic government and ruling for two years over what they declared to be "New Jerusalem" (via New Histories). They drove the old bishop out of the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Munster, and they enacted a series of highly controversial policies. These included the introduction of polygamy, the abolishment of the fiscal economy, and the redistribution of material goods.

According to The Conversation, the commune ran afoul of other communities because of these radical policies, leading to epic confrontation. Internal arguments led to fracturing from within, and external Catholic forces used this strategically to siege the city, declaring a clear and immediate danger.

These Catholic rulers sieged Munster and eventually took the city. They rounded up the ringleaders of the movement for imprisonment and public torture. St. Lambert's Church in Munster still hangs the cages where the body parts of the tortured men were displayed. This occurred after torturous deaths via fire and flesh-ripping tongs that lasted for more than an hour apiece, as reported by Executed Today. Today, the three cages remain a powerful reminder of the fate religious extremists could face.

Wedding celebrations turned into religious massacres

All hell broke loose on August 24, 1572, in Paris, France, according to Christianity Today. Well, at least, it felt like hell for the French Protestants known as Huguenots. Thousands had amassed in the city for the royal wedding of Princess Margaret of Valois to King Henry of Navarre. The Huguenots hoped the marriage would prove favorable for their growing ranks, as Henry of Navarre grew up Protestant. But they proved deadly wrong in their assumption.

At dawn on that August morning, the church bells of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois announced the assassination of Gaspard de Coligny, admiral of France and renowned Huguenot leader. After slaughtering the man in his bedroom, French troops threw him from the window to the ground below, where an angry mob amassed to mutilate his body. Two theories exist about the instigator of the massacre. Protestants accused Catherine de Medici of ordering the killings to capitalize on the flood of French Protestants into the city for the noble nuptials, per Britannica. But Catholics would later claim Henry of Navarre ordered the action out of a paranoid fear that his Protestant past might come back to haunt him.

Either way, the aftermath of Coligny's execution remained undeniable. As reported by Christianity Today, Catholic Parisians slaughtered roughly 3,000 Huguenots in Paris. Scholars also believe approximately 8,000 people were murdered in other cities in the weeks to follow. The horrific event, known as the St. Bartholomew Day Massacre, forced many Huguenots to flee France for elsewhere in Europe, as per History.

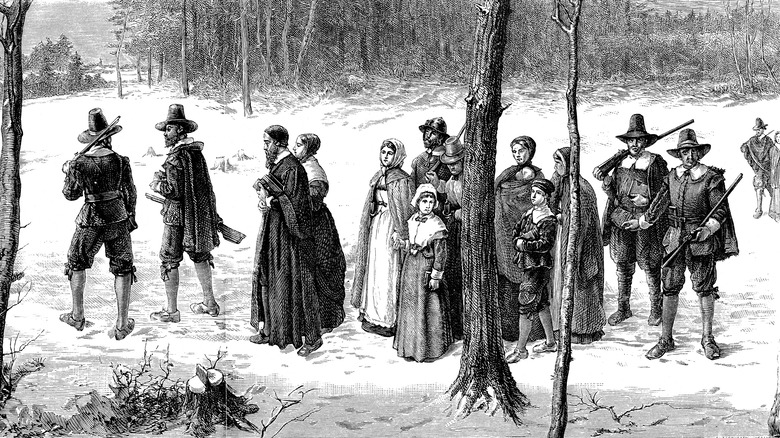

No place proved safe from religious conflict

Persecuted Protestants such as the Huguenots and the Pilgrims ultimately fled to the New World to escape the terrible religious persecution they faced. As reported by Totally History, before making this radical trip, however, sects such as the Puritans, Ranters, and Anabaptists fled to the Dutch Netherlands. There, they mistakenly believed they would find religious tolerance. Such was not the case.

Once these groups arrived in the New World, they spread out over time, establishing unique colonies where they could practice their beliefs freely. Their presence had a significant influence on their new homeland. Totally History reports that "The Reformation not only drove people to found America, but it also helped to establish the Constitution, which is the living document that governs the United States."

According to Small Planet Communications, Catholic nations like Spain aggressively pursued a foothold in the New World, too. Not only did they see obvious economic motivations for clinching ownership of the Americas, but they recognized opportunities to boost their numbers through the conversion of indigenous peoples. As with the colonization of North America, the Counter-Reformation in Central and South America resulted in local conflicts, open warfare, and the spreading of disease among indigenous populations.

Religious persecutions could swing in both directions

Religious turmoil didn't get relegated to mainland Europe alone. England also faced seismic religious upheaval, as reported by History Guide. As far back as the time of Bloody Mary, religious persecution swept the British Isles. The persecutions flip-flopped from Protestant to Catholic depending on the monarch.

It started with King Henry VIII's reign. Henry VIII was a vigorous defender of the Catholic faith, but this changed when the king decided to leave his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. The pope refused to offer the king an annulment, so he appointed himself the Supreme Head of the Church, which made dissolving his marriage a cinch.

Unlike in Germany, the English felt no great hatred towards the Roman Catholic Church. Rather, they generally followed Henry obediently due to his tremendous power. Things got sketchy with Henry's death and that of his son's, though. The king's daughter, Mary, became queen. A staunch Catholic, she worked zealously to place the nation back under the papal yoke. Over five years, she burned nearly 300 Protestants at the stake, hence the nickname Bloody Mary.

The Royal Museums Greenwich reports that Mary's persecution contributed to the flight of 800 non-Catholics from the country. Yet, her premature death would bring her Protestant sister, Elizabeth, to the throne, launching a retaliatory purge of Catholics. Only strategic dealings by Elizabeth during her long reign could unite the nation once more. But centuries of persecution (in both directions) created simmering hatreds. These would culminate in the post-Reformation English Civil War, in which Protestant Parliamentarians went toe-to-toe with Catholic Royalists (via Historic UK).

Getting executed for witchcraft was easier than you'd think

Between 1550 and 1700, more than 80,000 people went on trial for witchcraft in Europe, according to History. Half of these individuals got executed, and the vast majority were women, although men were also at risk. In the wake of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, History presents the argument that competing churches relied on witch persecution and trials to expand their flocks. Such persecutions also took place in the New World colonies. (Hello, Salem, Massachusetts!)

According to economists Jacob Russ and Peter Leeson (via History) , you can think about the competition between religious groups for new converts via witchcraft like Democrats and Republicans fighting for swing states. As they note, "Historical Catholic and Protestant officials focused witch-trial activity in confessional battlegrounds during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation to attract the loyalty of undecided Christians."

But why did witch trials see such a rise from 1550 to 1700? After all, these trials had all but disappeared between AD 900 and 1400. How did they get going once more? Again, it all stems back to what the Guardian refers to as "non-price competition between the Catholic and Protestant churches for religious market share." Apparently persecuting witches sold the general public.

Anti-Semitism exploded into the religious chaos

Anti-Semitism ran rampant during the Reformation, and it traveled from the top-down (via Lutheran Reformation). Although Martin Luther enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for taking significant steps towards religious freedom, he didn't extend this tolerance to the Jews. Some scholars have gone so far as to label the reformer a "rabid anti-Semite." And it appears these feelings got passed on to some of his followers.

Scholar Sascha Becker has long studied relations between Jewish communities and Christian religious groups. By examining the historical record, he's developed a fascinating picture of a Jew's precarious situation in Reformation and post-Reformation Europe. Records show higher Jewish concentrations in Catholic areas than non-Catholic ones. Becker also noted that when the Nazis rose in Germany before World War II, they first created anti-Semitic strongholds in Protestant (rather than Catholic) regions. Becker argues that this had a basis in the Protestant faith's permissive rules regarding money lending. Unlike Catholicism that had strict rules against money lending, Protestant financiers existed in direct competition with Jewish money lenders.

By scouring historical data, Becker concluded that after 1517, there was "a relative shift in pogrom intensity away from Catholic areas toward Protestant areas." In other words, tick off another reason to avoid time travel to the Protestant Reformation!