What Die-Hard Fans Don't Even Know About The Grateful Dead

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

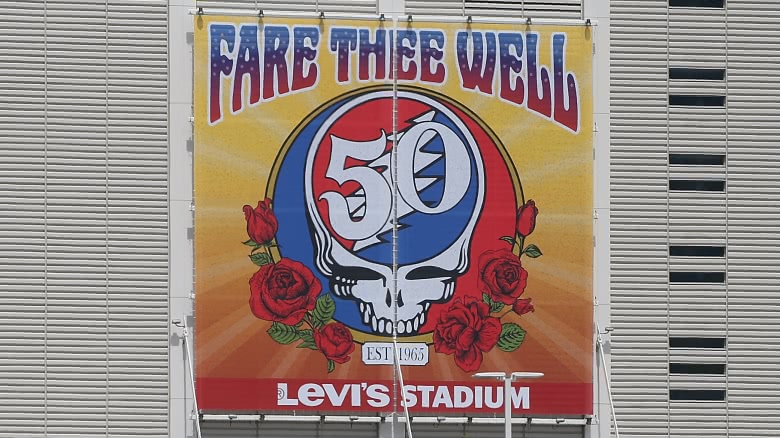

Fifty years after their founding and 20 years after the death of lead singer Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead remain one of America's most renowned bands. They did great rock songs as well as tunes that encompassed folk, country, bluegrass, jazz, Americana, the blues, and even disco. The common perception of their music is of psychedelic sounds and endless noodling. But they were a lot more than that. Here's the truth about the Grateful Dead.

They started in Palo Alto, not San Francisco

Palo Alto is a quiet, upscale college town located about 35 miles south of San Francisco and known as the birthplace of Silicon Valley. It was also the birthplace of the Grateful Dead, although Jerome John Garcia was born in San Francisco in 1942. He moved to Palo Alto after being discharged from the Army in 1960 for "lack of suitability to the military lifestyle." The San Francisco Weekly wrote that "he reportedly spent most of his time not following directions, missing roll call, and generally being young Jerry Garcia." Shocker.

Garcia met his future lyricist partner Robert Hunter in Palo Alto in 1961, and they briefly performed together as "Bob and Jerry." Soon after that, Garcia was in a horrible car accident that broke his collarbone. But it also made him put his career in high gear. He later described it as "the slingshot for the rest of my life."

He taught at Dana Morgan's Music Store there, where he jammed with future rhythm guitarist Bob Weir on New Year's Eve in 1963. That meeting of the minds was the impetus for the band that became the Grateful Dead. It wasn't until 1966 that the group moved to a house in 710 Ashbury Street in San Francisco, the city they were so identified with.

The Grateful Dead performed for both hippies and debutantes

In the mid-1960s, the Grateful Dead was the house band for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest author Ken Kesey's Acid Tests, where Merry Pranksters and others got together to take LSD and trip out. That era was immortalized in Tom Wolfe's 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. It's also how the band met Neal Cassady, the real-life Dean Moriarty of Jack Kerouac's On the Road. In addition, those shows were the inspiration for the ridiculous "Blue Boy" episode of Dragnet.

But the Dead also played for a very different audience back then. Peter Hartlaub of the San Francisco Chronicle was going through the newspaper's archives to find items on the Grateful Dead's 50th anniversary and found an amazing discovery—photos of the band performing at a 1966 debutante ball, as well as articles about the event. Hartlaub wrote that Bob Weir's sister was a debutante, which is how he thinks the band got the gig.

The Dead were pioneers in the world of business

Today, marketers talk about branding, and building tribes, and reaching out to your perfect customers. But the Grateful Dead did that for decades. They were pretty smart businessmen, according to David Browne, who wrote about the band in his 2015 book So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. He told Esquire that "there was nothing flower power about the Dead." Instead, "They were a pretty badass organization," he said. "It was a pretty tough, hardened world. It was not all group hugs and sunshine daydream."

Well before the rise of email and the Internet, the band were pioneers in communicating with their fans via direct-mail newsletters, and they later used modern technology. They allowed fans to record their music at shows, even giving them a special "tapers" spot at concerts, which helped spread their songs around. The Atlantic noted that the band also had a special phone number for fans to call for upcoming tour dates. They also sold tickets via mail order. Business professor Barry Barnes said in the article that "The Dead were masters of creating and delivering superior customer value" in a time where many businesses didn't worry about such things.

The band lost money thanks to an un-Grateful dad

Not all the band's business decisions were sound. Like hiring Mickey Hart's father Lenny. Mickey was not an original band member. He joined the band in 1967 as their second drummer, making them one of the only groups in history to have two drummers at the same time. His father Lenny, who was both a drummer and a reverend, ended up managing the group's money, but in 1970, the band realized he was embezzling from them. He then fled with their money, and Mickey left the Grateful Dead because he was so humiliated. (Hart would later return to the band in 1974.)

In August 1971, Lenny Hart was found in San Diego and arrested. A Rolling Stone article at the time said Hart was "baptizing Jesus freaks" when private detectives located him. John McEntire, who took over as the group's manager, told the publication: "So much of it's so cut and dry it's amazing how stupid we were." He said "It was a classic trip: Elmer Gantry coming in. We deserved it. But you wouldn't think he'd f*** his own kid."

The 1972 song "He's Gone" is about Lenny Hart, with lyrics like "steal your face right off your head," and "He's gone/Like a steam locomotive, rollin' down the track."

Garcia was in a Richard Nixon commercial

One of Richard Nixon's 1968 presidential ads talked about the youth of America, featuring photos of the counterculture. Twelve seconds into the ad, a photo of Jerry Garcia flashes on the screen. It's unclear how he ended up there. Maybe Nixon's ad people put his photo in because of the Uncle Sam hat Garcia was wearing.

Of course Jerry didn't vote for Nixon, but it turns out he didn't vote at all in that campaign, or in any other campaign after voting for Lyndon Baines Johnson as president in 1964. Garcia explained his lack of voting in a 1989 interview with Rolling Stone: "I don't feel there's anything to vote for yet. Constantly choosing the lesser of two evils is still choosing evil." Asked if he felt it was "possible for someone to like the Grateful Dead and the Republican party," he responded, "Yeah. We're American, too. What we do is as American as lynch mobs. America has always been a complex place."

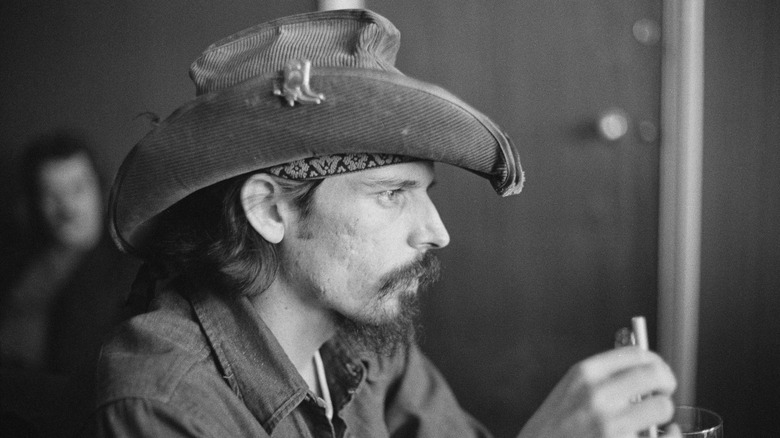

Pigpen died young, but not from too much drinking

For decades, the story was that keyboardist Ron "Pigpen" McKernan, who died in 1973, had passed on due to alcoholism. Like his onetime love interest and singing partner Janis Joplin, he was also a member of rock's infamous 27 Club. He was in bad shape before his death, having to take a leave of absence from the band due to health issues. While he was indeed a very heavy drinker, while the rest of the band preferred getting high, he had given up booze the last year of his life as his health declined. Instead, his death was reportedly due to congenital biliary cirrhosis, an autoimmune disease.

The band had a much more blues-based tone when Pigpen was with it, with him singing lead on "Turn on Your Lovelight," "Alligator," "Big Boss Man," and "Mr. Charlie," among others.

When Pigpen was with the band, he talked to the audience a lot, something missing from later shows, and was more of a frontman than Garcia was. As years went on, The Dead also took a different musical tone after his death, with more of a jazzy feel.

Even the band found Deadheads annoying at times

While the Grateful Dead was very fan-friendly, even they thought some of the adulation Deadheads had for them a bit much, especially if it took over the fans' lives. In The Other One, the 2014 documentary, Weir showed mixed emotions about those fans. "If it rings those lofty bells for them, what's wrong with that?" he said in the movie. "At the same time, if it takes your life down, that's another story." He continued, "If you're a kid and you want to spend a summer on the road, that's one thing. If you're selling drugs, I have limited sympathy."

He also talked in the film about how fans in the 1980s, especially after "Touch of Grey" became a massive hit, were "celebrating us way beyond what seemed reasonable." In addition, Weir felt that Garcia fell into hard drugs partly because of fans treating him like a god.

The band helped popularize yogurt in the U.S.

Yogurt is everywhere in American supermarkets today, but in the early 1970s, the product was considered a hippie-dippie food. Back then, Oregon's Springfield Creamery, founded by Ken Kesey's brother Chuck, sold Nancy's Honey Yogurt, the first yogurt in the US with live acidophilus cultures. But the business was struggling.

So Chuck Kesey reached out to the Grateful Dead to see if they could help. The band did a benefit show on August 27. 1972, in Veneta, Oregon, to keep the company going. Nancy's Yogurt is still around today. So is Sunshine Daydream, the concert film and recording of that concert.

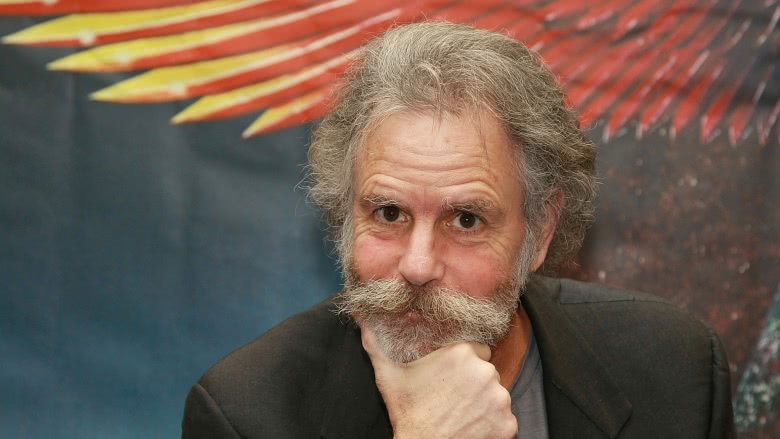

Bob Weir's biological father was an Air Force colonel

Weir was born in 1947 and was adopted by well-off parents from Atherton, California. He didn't quite fit in during his childhood. He had dyslexia but didn't know it at the time and ended up in a lot of different schools. His parents died in 1972, and sometime in the 1980s, his biological mother reached out to him. He wrote in an essay on Dozin.com, a Grateful Dead fan site, that when they met, they "did not exactly hit it off."

But she did give him the name of his biological father and told him that the father didn't know that she was pregnant. Weir hired a private detective and found out shortly thereafter that his father was not only an Air Force colonel but "the commanding officer at Hamilton Field, the local Air Force base in San Francisco." He wrote: "But because I am almost pathologically anti-authoritarian, I figured this would not go well for either of us." So he didn't do anything with the information for ten years.

Finally, in 1996, he figured it was time to reach out. He stated his name and explained the situation. His father replied, "The only Robert Weir I know is the guy that sings and plays with the Grateful Dead." And Weir responded, "Well sir, that would be me." Despite their different lives, they hit it off very well and became "very, very close," Weir said, and had similar personalities. Weir also found out that he had four brothers, several of whom also played guitar, and one who was a Deadhead. The documentary The Other One shows father and son, and the resemblance between the two in personality, looks, and voice is uncanny.

Altamont changed the trajectory of the band

For all the Grateful Dead's prowess as a touring band, they had mixed success when it came to concert festivals. They were overlooked at Monterey Pop and drugged out and awful at Woodstock. And in December 1969, they were supposed to be part of Altamont, and manager Rock Scully may have been involved in the idiotic idea of hiring the Hell's Angels as security. But the Dead wisely backed out of their set once they heard about the motorcycle gang beating up not just Jefferson Airplane lead singer Marty Balin onstage but some of the band's own crew.

According to Joel Selvin, author of the 2016 book Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels and the Inside Story of Rock's Darkest Day, the band "scurried out of the speedway with their tail between their legs," but he noted that "rather than run and hide" after the event, "the Dead absorbed Altamont as a lesson." Selvin thought the band's 1970 gentle, folky Workingman's Dead, very different from the psychedelic music they had previously been playing, was "a kind of reaction to Altamont."

They also wrote the song "New Speedway Boogie" about the debacle. And Selvin told the San Francisco Chronicle that after Altamont, "The Dead determined never to have anything to do with the mainstream audience ever again and dedicated themselves to their audience and their community," focusing on what they could control.

The man who made LSD also created the Dead's Wall of Sound

Augustus Owsley "Bear" Stanley III, known as Owsley, was legendary in the 1960s for manufacturing massive amounts of LSD—so legendary, the word "Owsley" is in the Oxford English Dictionary to define a very strong type of the psychedelic drug. But he also manufactured something else—the band's incredible Wall of Sound speaker system. The full system encompassed close to 600 speakers, put out over 28,000 watts of sound, and took a day to assemble.

The band only used it from 1972 to 1974, but the sound quality was amazing. "It was wretched excess," Weir told Vice.com. "But we were known for that. We would try anything. It did work for the people in the back rows. I think they got the full benefit of that PA." Unfortunately, it was also far too expensive for the band to keep on using.

Garcia got the entire band into the Rock and Rock Hall of Fame

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has a rule that musicians can only be inducted "become eligible for induction 25 years after the release of their first record." So technically, when the Dead were elected into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, only the original members of the band should have been inducted, and not later additions like Donna and Keith Godchaux and Brent Mydland. But Garcia insisted that everybody in the band had to be inducted, not just those who were in the band 25 years before. He also fought for Robert Hunter, the group's main lyricist, to be included as well. He won, and 12 members of the band were included in 1994.

What Garcia did made him a true mensch, especially since he himself cared so little about the induction he didn't even show up (the band brought a cardboard cutout of him instead). But he knew the recognition was important to his bandmates.

On the other hand, Bruce Springsteen didn't fight for the E Street Band to be inducted along with him in 1999. It took 15 more years for them to finally make it in on their own. Springsteen admitted in 2014 when he gave the induction speech for his band that although guitarist Steve Van Zandt asked him to fight for them back then, he wouldn't do it, saying, "perhaps the shadows of some of the old grudges held some sway." Too bad saxophonist Clarence Clemons was not alive to enjoy the honor. He died in 2011.

Garcia was addicted to cocaine, heroin, cigarettes, and food

People associate pot and LSD with the Dead, and Garcia certainly partook of those drugs. However, it was cocaine and heroin, the antithesis of hippie drugs, that really took its toll on Garcia. In early 1985, the band did an intervention on him. He agreed to go to rehab, but before he did, he was arrested in Golden Gate Park after being spotted freebasing cocaine in his car.

Then in 1986, he nearly died from a diabetic coma, with his diabetes brought on by overeating. The Los Angeles Times notes that Garcia also was a heavy cigarette smoker. He battled drugs on and off for the rest of his life and died in rehab in 1995 from a heart attack at 53, looking decades older thanks to obesity and hard living.

Garcia was also tired of touring. He said in a 1991 Rolling Stone interview that the band had been "running on inertia for quite a long time," but because they had a lot of people on the payroll "that we're responsible for," he said "we're reluctant to do anything to disturb that."

In retrospect, when Garcia got addicted to drugs again in the mid-1990s, they should have taken time off from touring to let him get clean. But according to David Browne's book So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead, the band had $750,000 in expenses each month with all the people on their payroll. And Garcia had alimony payments of over $20,000 a month alone. So they kept on playing, even though he was forgetting lyrics and had a hard time playing guitar thanks to clogged arteries and carpal tunnel syndrome.

By 1995, he was in really bad shape—so bad, he told his driver that May, "I won't see the end of the year." Three months later, he was dead.

Members of the band talk about Garcia's addiction in the 2017 Grateful Dead documentary Long Strange Trip. Mickey Hart says that "It shows you how lonely it is when people want to pick you apart and give you no peace just because they love you to death. It's kind of tragic."

Bandmate Bob Weir later admitted he was Garcia's "bagman," doling his supply out to him over the years so he didn't take too much. He said he had a message for fans today: "Bottom line: you're better off straight."