The Untold Truth Of The Legend Of Zelda

It's hard to believe, but the first The Legend of Zelda game came out over three decades ago. That's like ten Weird Al Yankovic albums ago. There are roughly 20 titles in the series now, on about a dozen different systems, and one game even doubled as a wristwatch, because sure, why not? That's a lot of history, with some parts weirder and more obscure than others. We dug around for some of the more surprising revelations.

The original version of the the first game was planned to be completely different

One of the earliest cartridges for the Nintendo Entertainment System, 1986's The Legend of Zelda brought rudimentary strategy and role-playing elements to a gaming market largely dominated by platformers and action titles. The world of the game is a tight and well-contained fantasy setting with a distinctly fairy-tale feel, full of dragons, magic swords, hidden passageways, dungeons, forests, and literal fairies. It's strange to think that the first draft of the game was more of a sprawling, cyberpunk, Highlander-esque, fantasy/sci-fi, time-traveling mess of a thing.

Speaking to French gaming magazine Gamekult in 2012, creator Shigeru Miyamoto revealed that the original plan for the game was that the Triforce was a series of microchips you had to collect and put together. The game would have taken place in both a fantasy past and a sci-fi future. That would have changed the entire feel of the game, and short of finding some time-traveling microchips ourselves, there's honestly no telling what that game would have really been like.

Another fascinating part about early drafts of the game was the possibility of having players build their own dungeons. Miyamoto and Co. scrapped the idea, meaning mid-'80s gamers were forced to scratch their level-building itch via Excitebike.

The second quest for Legend of Zelda was created because of a programming mistake

A lot of early Nintendo titles included a second quest to extend play time, withhold special endings, or ratchet up the difficulty. The Legend of Zelda is one of the first to have a distinct second quest with new maps and puzzles, as well as an increase in difficulty. In the first quest, for example, the dungeons have different shapes based on different animals and symbols. But in the second, the first five dungeons spell out the name ZELDA. Items have different effects, and the overworld map has several key alterations, as well. It's almost like getting a whole new game, which is funny, considering its inclusion was the result of a last-minute screw-up.

When the game was finished, the developers accidentally only used up half the data they had available. Miyamoto played through the game and was really happy with how it turned out, so instead of going back to the drawing board, he suggested creating a distinct second quest to fill up the rest of the data.

Maybe they could have used that space to, y'know, include that dungeon building sub-game that was part of earlier drafts? Yeah, we're pretty bitter about that hitting the cutting room floor.

The Legend of Zelda and Super Mario Bros. were developed simultaneously, and shared resources

In the early days of developing Nintendo titles, resources were pretty thin and were shared frequently. Back then, Nintendo employees shared a bathtub, so sharing a few sprites and ideas must have seemed fairly tame in comparison. This is particularly noticeable detailing the development of the classic games Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda, which occurred simultaneously. The teams worked so closely together, the Zelda project was originally named "Adventure Mario."

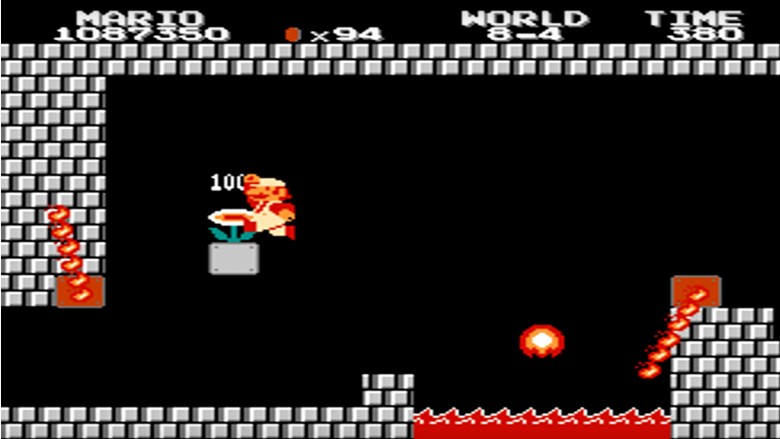

In "Iwata Asks," the series of probing interviews conducted by Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata, the gaming titan's head honcho elaborates on some of these shared resources. For instance, the infuriating "fire bars" that appear in all the castles in Super Mario Bros. started out in Zelda before being swapped over. Others were hinted at in the Japanese manual for Zelda, where they describe the boss Manhandla as related to the Pirahna Plants from Super Mario Bros. (they clearly use a similar sprite). It's also worth noting that both Bowser from Mario and Gannon from Zelda were known as "Great Demon King" in their respective Japanese manuals.

Incidentally, another boss in the game, Digdogger, is actually borrowed from an early NES game called Clu Clu Land. Apparently the developers couldn't just have a cycloptic sea urchin, they had to have a particular cycloptic sea urchin that had appeared in a previous top-view puzzle game released the year before. Because reasons.

The Legend of Zelda theme almost didn't exist

It's hard to believe, but the opening crawl music to The Legend of Zelda, an early composition by now-legendary Nintendo composer Koji Kondo, almost never happened. It's very likely one of the most recognizable pieces of video game music in existence, but it was actually frantically composed to replace a piece of classical music Nintendo wasn't allowed to use.

For most of the design and programming of the game, the title and intro screen had a completely different tune: "Boléro" by French composer Maurice Ravel. The developers believed "Boléro" was in the public domain at that point, but last minute research proved otherwise. Not wanting to delay production of the game waiting for the song's copyright to expire, they tasked Kondo with putting together a track, and after pulling an all-nighter, he created the iconic work, which has been re-interpreted and referenced countless times since.

Not a bad legacy, considering Kondo just jumped in and covered the slack for the rest of the team that had dropped the ball, like it was some chemistry class group project.

The Legend of Zelda games bypassed Nintendo of America's religious censorship (sort of)

Learning their lesson from the Atari video game crash, Nintendo restricted which games were allowed to be made on their system by requiring an "Official Nintendo Seal," indicating that the game met quality control standards and was also free of objectionable content.

A particular guideline Nintendo of America applied in order to make non-controversial games was a restriction on religious or ethnic symbols. This meant that symbols like crosses (even the Red Cross) had to be removed from in-game graphics. The application of these rules was inconsistent, however. In Castlevania, the "cross" weapon was made into a boomerang, but the Zelda games kept crosses on shields, gravestones, and other items. A cross is actually used as an item in Zelda II, allowing the character to see invisible enemies.

Not to say that the Zelda games were completely immune to the rules, however. The "Bible" was turned into a "Magic Book" (but still had a cross on it). The villain Agahnim from Link to the Past was changed from a priest into a wizard, and even the name Link to the Past was changed from the original Japanese title, Triforce of the Gods, which honestly isn't as cool of a name anyway. Sounds less like the wild dimension-hopping adventure we got and more like a straight-to-VHS Conan the Barbarian knock-off.

The Zelda timeline is completely bonkers

Through a timeline suggested in the 2011 Zelda art book Hyrule History, we more or less have an idea when each game takes place. And because the people that created Zelda probably hate us or something, the first two games are actually the final two chronologically and take place on the darkest alternate timeline presented by alternate outcomes of the quest in Ocarina of Time. Seriously — you may need to bust out the whiteboards to make sense of all this.

It makes sense, strange as it may sound. The Legend Of Zelda II: Link's Adventure ends with Link preventing Ganon from being resurrected. You never even see the Piggly Wiggly "Demon King" unless you game over. Also, compared to the later games of the series, Hyrule is a desolate Mad Max wasteland in the first two NES games. Other games are full of bustling towns, but in the first two titles, everyone is in hiding behind magic doors and in secluded pathways.

To make things extra confusing, it appears that Breath of Wild, minus some sort of mystical revelation, doesn't appear to fit cleanly into the bonkers timeline we have to work with.

The "Chris Houlihan" room from Link to the Past is named after a fan

A guy named Chris Houlihan won a contest in Nintendo Power in 1990, earning the right to have his name appear "in an upcoming game." That game ended up being A Link to the Past, but it's unclear if Mr. Houlihan ever even saw his name on screen.

The so-called "Chris Houlihan Room" is a sort of glitch/error code that pops up when the game is attempting to transition to a screen and can't quite figure out where to go next. It was a super-rare failsafe back in the Super Nintendo's heyday, essentially, but gamers have since figured out a few oddball ways to trigger it. The simple room is full of blue rupees and contains a telepathic tile with the following message: "My name is Chris Houlihan. This is my top secret room. Keep it between us, OK?"

Why would the game developers make finding this room such a hassle? Seems pretty cruel to take what should be a guy's triumph at winning a contest and burying it away so far in the code that you practically have to break the game to find his prize. Hopefully Chris got a kick out of it.

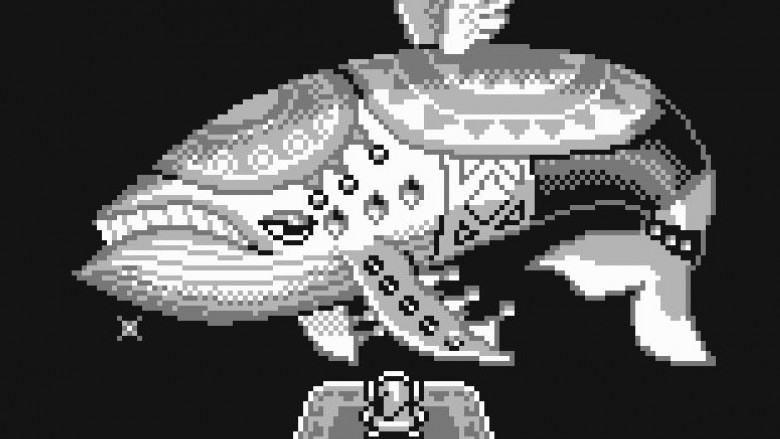

Link's Awakening was influenced by Twin Peaks

Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening is a pretty twisted game. It has all of the mechanics of a Zelda franchise game but everything is ... off. And it doesn't even have that whole "we literally just stuffed all our characters into someone else's game" aspect that also made Super Mario Bros. 2 so full of strange dreamlike logic, although both games take place in dreams.

The answer is simultaneously simpler and much more unexpected and bizarre: the game was heavily influenced by the work of David Lynch and Twin Peaks, in particular. The developers were very intrigued by how tightly the plot revolved around a small town full of "suspicious characters" and wanted to replicate that sort of experience within the already established Zelda universe. Having everything take place within the confines of a small island provided that limited environment, which kinda makes you wonder if, in turn, a Game Boy-playing J.J. Abrams was taking notes for Lost a decade later.

If you really wanna dig, there are a lot of incidentals in the game that match up to the series the developers already admitted inspired them. Owls, doppelgangers, zigzag floor patterns, Native American imagery — all sorts of wild stuff. Honestly, the frequently repeated Twin Peaks quote "The owls are not what they seem" is practically a spoiler for the game. All that's missing is the Log Lady.

The Phillips CD-i games were pretty much doomed to failure

The Phillips CD-i Zelda games really didn't have to be as terrible as they turned out. It all started when Nintendo and Sony got into a messy fight about developing a CD-based video game system and brought Phillips into it. That was entirely Nintendo's fault. Thing is, acquiring some Legend of Zelda character properties wound up being Phillips' consolation prize for basically being the hot boytoy Nintendo used to make Sony jealous, not realizing it would lead to a messy divorce that would screw everyone over except for Sony.

The Zelda game properties for the Phillips CD-i actually started out promising, despite the almost total lack of involvement from Nintendo. Philips brought in Dale DeSharone, a developer famous for the critically acclaimed RPG adventure game Below The Root. Then things went to crap.

The release of the Phillips CD-i system kept getting pushed back. DeSharone's supervisor, Steve Yellick, took his own life during the early development stages, which made him now the lead of a project he wasn't really planning on investing years into, but now couldn't escape. Philips insisted on sticking with 1987 technology, despite the release date inching closer and closer to 1991. Budget constraints meant the cut-scene animation for two of the three games was farmed out to Russia, leading to the histrionic flapping mess of a "plot" that the internet has made fun of ever since.

Phillips justified screwing over DeSharone and the rest of the game design team because they wanted the CD-i to be a "multimedia system" rather than just for games, which they practically sneered at. In the end, however, Phillips lost a billion dollars with the CD-i experiment, which serves them right for dragging these classic characters through the mud.