History Of Speaking In Tongues Explained

What do you think of when you hear the phrase "speaking in tongues"? If you're like many Americans, you might associate it solely with Pentecostals. What's more, images might come to mind of snake handling and poison drinking. Others might think of Pentecost, when Jesus' disciples claimed tongues of fire appeared over their heads, and they spoke in all the intelligible languages of the known Roman world, or about foreign languages spontaneously spoken (and translated) in a church setting.

Which of these associations proves correct? All of them. Speaking in tongues (aka glossolalia or xenolalia) has a long history that stretches back into ancient times yet remains a vital part of some worship traditions to this day. What's the difference between glossolalia and xenolalia? According to Britannica, glossolalia refers to unknown tongues. As for xenolalia? It relates to speaking a human language that the speaker doesn't comprehend (via Definitions).

Contrary to popular belief, many "tongue speakers" are not members of fringe Christian movements. According to historian of American religion Grant Wacker (via New York Times) many early Pentecostals "paralleled the demographic and biographical profile of the typical American" and the same source reports that Pentecostalism was "the largest form of Christianity after Roman Catholicism and the fastest growing" in 2001. Keep reading for more surprises when it comes to the fascinating and diverse history of speaking in tongues.

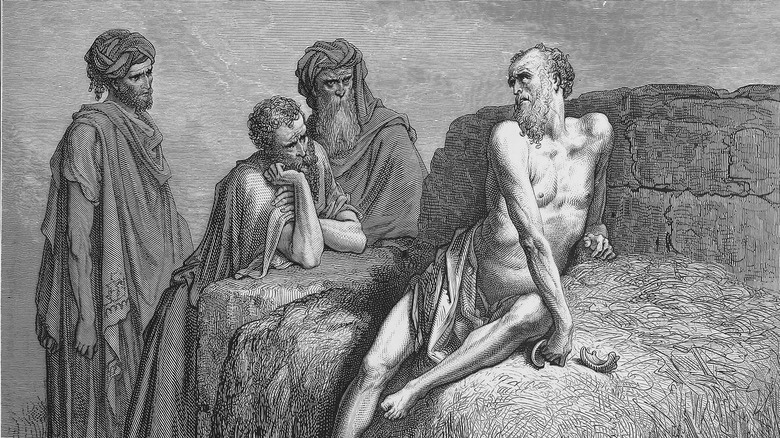

Job's daughters spoke in angelic tongues

What are some of the oldest references to people practicing glossolalia? Speaking in tongues is referenced as a gift that Job's daughters possessed in the Testament of Job, an extra-biblical work (via "An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives"). According to this tradition, the daughters — Amaltheia, Hemera, and Kasia – received special garb (sashes or girdles) as an inheritance from their father.

Job told his daughters that their inheritance would be "better than the portion of the sons, because it is from Heaven," as reported by Jewish Women's Archive. What did these garments do? They gave the girls the ability to speak in unknown tongues. Each of the girls uniquely manifested this gift.

Besides speaking in unknown languages, Job's three daughters also saw the total transformation of their lives when they donned their sashes. They lost their cares for the world, and they became ecstatic in praise and worship of God. Hemera improvised in the "hymnic style of the angels," according to Gerald Hovendam's book "Speaking in Tongues: The New Testament Evidence in Context." Kassia spoke in the language of the "archons" (heavenly rulers), and Amaltheia spoke in the tongue of the cherubim.

Glossolalia has ancient origins

While people familiar with Christianity might assume that the practice of glossolalia started in the New Testament at the time of Pentecost (Shavuot in Hebrew), the phenomenon has much older origins.

The Jewish festival of Shavuot commemorates the first fruits of the wheat harvest and revelation of the Torah. According to the account, God gave the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai "in one magnificent utterance ... yet more than one utterance was heard by the people" (via Random Groovy Bible Facts). But some rabbis have taken this idea much further. They believe that the Israelites not only heard the words of the Lord, but they saw the sound waves of His words "as a fiery substance." Some religious leaders believe this culminated with the transmission of the message in 70 languages, many incomprehensible. As reported by Firm Is Israel, "God's voice, as it was uttered, split up into 70 voices, in 70 languages, so that all the nations should understand."

The Ten Commandments set an important precedent for the Israelites' relationship with God and fellow human beings. As argued by the International Christian Embassy Jerusalem, it also set the stage for a remarkable event in Christian history: Pentecost.

Speaking in tongues is connected to tongues of fire

The revelation of God's word is accompanied by tongues of fire in both Exodus and the Book of Acts, and the texts share crucial religious significance. Why? Because in both cases, God revealed his character to humanity, providing a standard by which even the worst sinner could be transformed for the better (via the Jerusalem Connection Report).

Exodus also had implications for the priestly class, and how their leader (the high priest) communicated with God once a year in the Holy of Holies located at the Temple. How do we know this? According to the Jerusalem Connection Report, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus Flavius described how God spoke to the high priest via illuminated letters engraved on the priest's breastplate. This symbology denoted the religious authority of the high priest as a figure capable of communicating directly with God.

Does anyone else mention the high priest and tongues of fire in first-century Palestine? Yes, the Essenes of Qumran copied and preserved the Dead Sea Scrolls and various other Jewish texts (via the Library of Congress). These include a scroll entitled "The Tongues of Fire." According to the International Christian Embassy Jerusalem, the surviving parts of the scroll tell of "how tongues of fire would descend on the High Priest and speak through the Urim and Thurim and the stones on the breastplate of the High Priest."

Judaean views of Hebrew and the language of angels

If you could travel back in time to speak with an ancient Judaean, they might tell you two things about the language of angels, according to Eben de Jager's "An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives." The first, known as the hebraeophone theory, was that the angels spoke Hebrew. The second — the angeloglossy theory — said that angels spoke "esoteric angelic languages."

The first instance of Hebrew-speaking angels comes from the Book of Jubilees, considered the oldest source on this topic. The concept of specific languages having religious significance is far from unique to Judaism, but it's vital to understanding how early Christians perceived tongues.

According to de Jager, some scholars understand "praying in the Spirit" to refer to glossolalia. What's more, the Apostle Paul had a thoroughly Jewish perspective regarding tongues. "Paul thought of glossolalia as speaking the language(s) of heaven," the paper posits. Within this context, these utterances represented a devotional language that Paul encouraged followers to practice.

In 1 Corinthians 14:18, he writes, "I thank God that I speak in tongues more than all of you." That said, de Jager explains that he qualifies this statement (and others about tongues) as a prayer language used in private. The only exceptions to this? Situations where someone (besides the speaker) with the gift of interpretation translates the tongue-speaker's message.

Pentecost and the early Christian Church

While the feast of Shavuot or Pentecost (aka Whitsunday) has long had religious significance for the Jewish people, it's unclear when and how the earliest Christian churches observed the holiday (via Britannica). What happened during the New Testament event? According to Biblical Archaeology, Jews from across the diaspora gathered to hear the disciples speak. A melting pot of cultures, the audience members conversed in a diverse and rich variety of languages.

When the tongues of fire descended on the disciples, "each one heard them speaking in the native language of each [nation]." Biblical scholars still debate the nature of the miracle that occurred at Pentecost. Some claim the event involved two miracles, but others argued that only one miracle took place: the spontaneous ability to speak in another language.

Biblical Archaeology also explains that some scholars interpret what happened during Pentecost as the opposite of the events at the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11:1-9, when God confounded the nations by scrambling their languages. "While Pentecost doesn't reverse the languages at Babel, it overcomes the problem for the sake of the salvation of the nations," Ben Witherington III argues (via Biblical Archaeology).

Christian references to the holiday suggest a 50-day observance period that began and ended with baptisms. Historically, some Christians also wore red vestments and even dressed the altar in red, symbolizing the "tongues of fire," according to Britannica.

Paul called it 'praying in the Spirit' and the 'language of Heaven'

Paul the Apostle referenced speaking in tongues in several of his epistles. He described the practice as "praying in the Spirit" and considered it a devotional language for use in a private setting, per "An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives."

But some argue that Paul's beliefs about glossolalia don't stop there, proposing that in saying "For if I pray in a tongue, my spirit prays but my mind is unproductive" in 1 Corinthians 14:14, he is alluding to the practice as the Holy Spirit helping believers to pray for things they don't even know to ask for. It's also argued that Paul contrasts the intellectual tradition of praying with that of doing so in unknown languages, representing a leap of faith (via Blue Letter Bible).

According to Crosswalk, Paul describes glossolalia as a form of "personal edification" that involves speaking "not to men but to God" (1 Corinthians 14:2-4). In other words, it wasn't a practice for show or religious prestige. Instead, it should occur in the privacy of one's prayer closet, fortifying faith and strengthening the believer's personal relationship with Jesus through the Holy Spirit.

This interpretation of speaking in tongues leads to some fascinating questions about Pentecost. After all, this miracle involved speaking in real-world languages. And more particularly the languages of those present in the crowd that day. In his book "The Holy Spirit and Spiritual Gifts," author Max Turner distinguishes the tongues spoken publicly in the Book of Acts from those for self-edification. He argues that Luke, the author of the Book of Acts "would not wish to suggest that the apostolic band merely prattled incomprehensibly, while God worked the yet greater miracle of interpretation of tongues in the unbelievers" (via Crosswalk).

Some early Church fathers rocked unrecognizable lingo

References to speaking in tongues also appear in material written by early theologians such as Tertullian, as reported by Evangelical Focus. Tertullian discussed the spiritual gift of interpreting these languages in 207. Others who mentioned this practice include Novatian in 360, Justin Martyr in 150, Eusebius in 339, Chrysostom in 407, and Augustine of Hippo in 430.

In the second century, Irenaeus referred to church members speaking in diverse languages "through the Spirit," per Unsettled Christianity. These messages stood in stark contrast to a group of Christians who would develop the theological concept of Cessationism. What was Cessationism? The argument that the miracles of the New Testament, including healing and speaking in tongues, started and ended with the first generation of Jesus' disciples. This controversy would have significant implications for church unity.

It also explains why later generations of "miracle-working" Christians would get derided and marginized by conservative Cessationists. There's no faster way to get kicked out of many churches today than publicly praying "in the Spirit." Interestingly, Irenaeus's interpretation of the role of glossolalia to the faith couldn't have been in greater opposition with many mainstream beliefs today. According to Unsettled Christianity, Irenaeus "seems to take the position that speaking in tongues is a sign of spiritual maturity, of spiritual perfection."

Glossolalia takes a back seat

At this point, you may be wondering how speaking in tongues went from an accepted Christian practice to something reserved for snake handlers and poison drinkers (as the stereotype goes). According to LDS Church History, it all started in the 12th century, when Bernard de Clairvaux proclaimed that no more extraordinary miracles existed than the positive changes wrought in believers' lives. Essentially, things classed as "supernatural," such as speaking in tongues, no longer took place among believers.

Besides minimizing the role of glossolalia in contemporary worship, other medieval church figures associated the practice solely with known languages. In other words, unlike the ancient Judaeans who often linked tongues with angelic languages, medieval church figures such as Hildegard von Bingen and Thomas Aquinas thought tongue-speaking involved commonly used, interpretable languages.

According to Science Doc Box, Von Bingen even claimed to have the ability to speak and write fluently in Latin with no training. What's more, scholars such as Guibert de Nogent mention women also speaking in tongues that proved translatable. Thomas Aquinas didn't claim to have the gift of speaking in tongues, but he did write about it. Interestingly, he notes that Jesus never exhibited the gift of glossolalia. So, why did his disciples? In his iconic "Summa Theologica," Aquinas hypothesizes that they would have needed this skill in order to spread the word of the gospels, arguing that "both Paul and the other apostles were divinely instructed in the languages of all nations sufficiently for the requirements of the teaching of the faith."

Other groups revived the art of sacred babbling

The Moravians earned a reputation as one of the oldest Protestant denominations globally. But they also became known for speaking in tongues long before Pentecostals and Charismatics hit the scene, as reported by Moravians. The sect also set up a continuous prayer watch that ran uninterrupted 24 hours a day for 100 years.

A group of 17th-century French prophets known as the Camisards spoke in incomprehensible languages, according to Michael Pollock Hamilton's "The Charismatic Movement." They would sometimes also interpret the tongues they spoke, and they differed from the Cessationists when it came to the role of miracles in today's world. They claimed, "God has no where in the Scriptures concluded himself from dispensing again the extraordinary Gifts of His Spirit unto Men." Despite their radical beliefs, the French prophets took social respectability to the next level, maintaining well-kept appearances, per "The French Prophets: A Cultural History of Religious Enthusiasm in PostToleration England (1689-1730)." In other words, they represented a far cry from stereotypes about backwoods tongues speakers.

Early Quakers also participated in glossolalia, according to PCPJ. You'll never look at the Quaker Oatmeal guy quite the same! While the thought of sober Quakers getting caught up in ecstatic speech might appear counterintuitive at first glance, think again. As it turns out, the Quakers have long-held linkages with the Charismatic Movement.

Speaking in tongues went wild in the 19th century

By the 19th century, an outbreak of glossolalia took place in locations across the Christian world. According to Richard Hogue's "Tongues: A Theological History of Christian Glossolalia," a German aristocrat of the Prussian Guard named Gustav von Below founded a religious order with his brothers in Pomerania. Their worship included prayer meetings of a charismatic bent, and believers from all walks of life received a warm welcome at von Below's estate at Redenthin. The meetings were "dominated by singing in tongues," and the movement attracted notables including Otto von Bismarck.

The founders of the Mormon church also extensively referenced speaking in tongues in their writings. According to Dialogue Journal, "numerous sources describing the origin of speaking in tongues in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints credits Brigham Young with introducing the practice to Joseph Smith."

What's more, a minister within the Church of Scotland, Edward Irving, wrote about a woman named Mary Campbell (via Apostolic Archives International). Irving claimed the Holy Spirit came upon the woman, bedridden with illness, during worship. The event caused her to speak with "superhuman strength" in a language that nobody recognized. Campbell's experience contributed to the rebirth of speaking in tongues in the Christian movement. By the spring of 1830, a handful of Scottish women followed suit, and observers claimed "tongues of flames" descended on some of them.

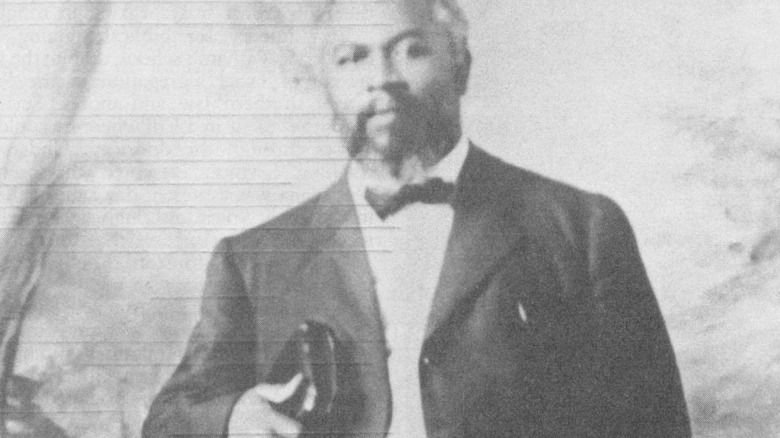

From Asuza Street to neuroscience

In the 20th century, Pentecostalism and a later Charismatic Movement brought glossolalia back to the forefront. What proved the pivotal event in these movements? According to the Apostolic Archives, the Azusa Street Revival, a Pentecostal revival led by African American preacher William J. Seymour, contributed to a significant movement in southern California.

Eyewitnesses described the Azusa Street Revival as a frenetic admixture of miracles, glossolalia, "dramatic worship services," and indiscriminate fellowship between people of every class, color, and background. The movement endured heavy criticism, particularly from bewildered members of the media. Nonetheless, it is considered to be the "primary catalyst" of a Pentecostal resurgence in the 20th century (via Assemblies of God).

In 2006, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania studied images of peoples' brains while they spoke in tongues, and they came to some fascinating conclusions (via the New York Times). Contrary to centuries of stigma, individuals who speak in tongues rarely have mental illness, and they often prove more emotionally stable than those who don't. Their conclusion? The act of glossolalia involves submission to a higher power leading to a "very intense experience of how the self relates to God," per Science. Moving forward, it'll be fascinating to see what science has to say about this ancient practice.