How The Supreme Court Could Have Saved The Reconstruction Era

It's a common axiom that when a person votes for the president of the United States, they're also voting for the future of the Supreme Court. The argument is supported by the fact that presidents appoint Supreme Court justices who then serve in their roles for the rest of their lives or until they retire. And the makeup of the Supreme Court determines so much about the laws of the United States — as the final stop for many laws passed by Congress, a "nay" from the highest court in the land can derail progress that seemed inevitable.

This was certainly the case in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. Per NPR, 4 million formerly enslaved people were freed in 1865 when the 13th Amendment was ratified, abolishing slavery. Afterward, the 14th Amendment establishing Black Americans as citizens with equal protection under the laws of the country, and the 15th Amendment gave Black men the right to vote. As reported by The New Yorker, seven Black men were elected to Congress via the first post-war elections, including Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first Black senator to represent Mississippi.

In 1875, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. Proposed by Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, it guaranteed that every American citizen was "entitled to the full and equal enjoyment" regardless of race or color. Speaking to NPR, constitutional scholar Lawrence Goldstone said: "They wanted the federal government to take these four million newly freed slaves and integrate them fully into society virtually immediately." But the Supreme Court wouldn't let that happen.

Civil rights were declared unconstitutional in 1883

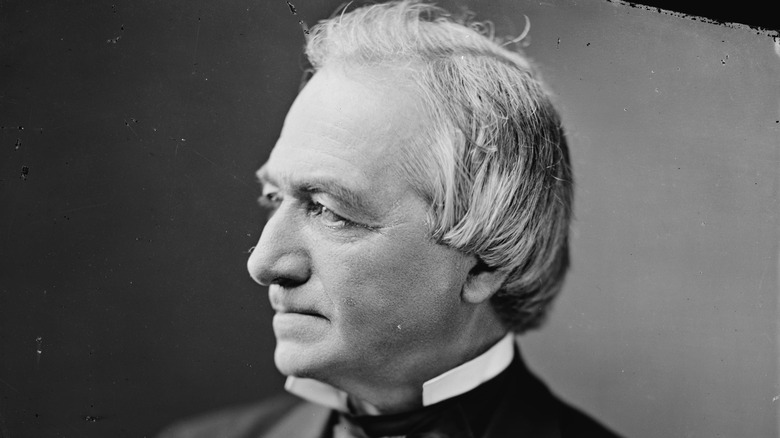

In 1883, the Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional and not authorized by the 13th and 14th Amendments. As reported by Thirteen, Justice Joseph Bradley (shown above) wrote the majority opinion, which said that "the denial of equal accommodations in inns, public conveyances and places of public amusement (which is forbidden by the sections in question), imposes no badge of slavery or involuntary servitude upon the party, but at most, infringes rights which are protected from State aggression by the XIVth Amendment."

This opinion opened the door to the racist Jim Crow laws that followed, as well as laws passed in southern states that made voting extremely difficult for Black citizens. Notably, "Black Codes" limited the rights of Black people to work and relocate, per The New Yorker. As reported by NPR, this was enforced by violence from the Ku Klux Klan, which was protected by the Supreme Court in 1883 when it declared the Enforcement Act of 1871 — which forbade Klan members to meet — to be unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court continued legalizing racism

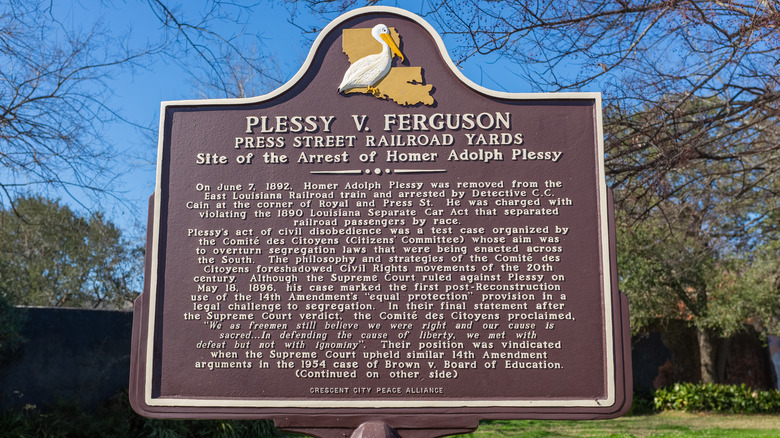

The Jim Crow laws were further legitimized by the 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson. As reported by Thirteen, Homer Plessy, a light-skinned Black man, bought a first-class train ticket in Louisiana and was arrested, imprisoned, and convicted of breaking an 1890 Louisiana state law that "provided" separate railway cars for white and Black travelers. Plessy filed a petition against John H. Ferguson, the judge that ruled against him, and it went to the Supreme Court. There, eight justices ruled that separate seating was in fact Constitutional, contending that the "fallacy" of Plessy's argument "consist[ed] in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it."

Many kinds of racial segregation remained legal right up until President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.