The Surprising Truth Behind The Bizarre Codex Seraphinianus

Sometimes, in the arts, the line between laudable creativity and haphazard incomprehensibility gets strangely blurred. Adjectives like "tour de force," "auteur," and "groundbreaking" get tossed around willy-nilly. It's too easy to point to a work that's difficult to understand and declare it "genius."

In the world of literature, some books — like the rambling sprawl of "Gravity's Rainbow" by Thomas Pynchon, the semantic-shattering "Finnegan's Wake" by James Joyce, or the fake-poem-by-a-fake-novelist "Pale Fire" by Vladimir Nabokov — are justifiably called any of those words. But if you read a line like "dark plumbs the smoothbore teeth flexed rigid" taken out of context and left to hang like a random strand from Allen Ginsberg's legendary beat poem "Howl," is that merely an exercise in poetics? Does it have a single, concrete meaning? Put technically: Does creative relevance require semantic intention?

In the visual arts, some critics called the renowned drip-drop painter Jackson Pollack's work "mere unorganized explosions of random energy, and therefore meaningless," as The New York Times quotes. An article on Unaffiliated Press goes one savage step further with its headline, "Jackson Pollock is Trash and Abstract Expressionism Needs to Die." Psychology Today, though, when reporting on a study about abstractions and ambiguity, found that tolerance for abstraction tends to scale with education: the more you understand, the more you appreciate.

So what are we to make of an utterly abstract text stuffed with surrealistic imagery and a fake language? Is it genius? Meaningless? Enter the "Codex Seraphinianus."

An encyclopedic fever dream of otherworldly visions

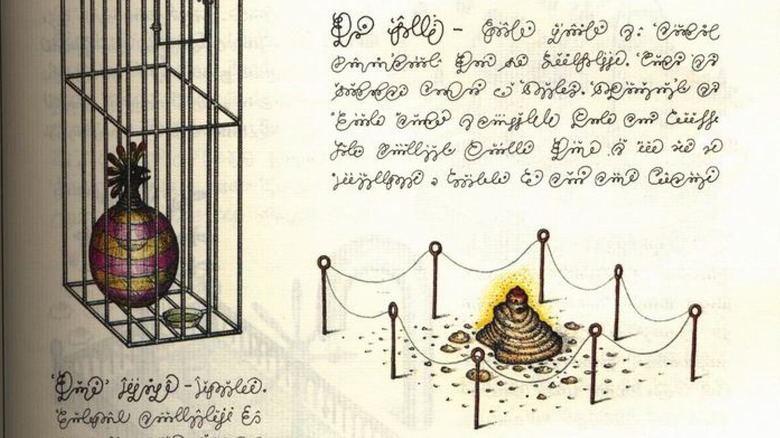

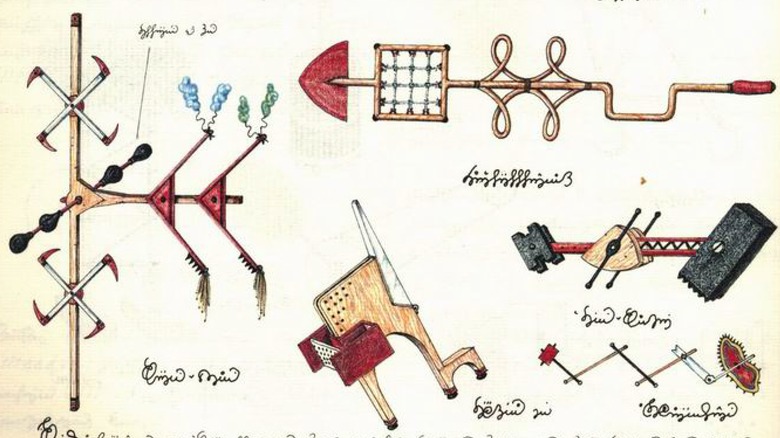

The second you crack open the "Codex Seraphinianus" — available in full online at Holy Books (more on the "holy" angle later) — you'll likely be frowning, tilting your head, and muttering "what in the world?" By page 11, you've got an encyclopedic table of organic plant-looking diodes, green splatters, musical instrument shapes, coiled shells, and more. By page 26 we've got a capsule-filled transparency cut into the side of a banana; page 58 a pink jelly ring pinching itself off into ladybug shapes; page 96 a white horse with a pom-pom on its head grown out of a larva with wheels; by page 192 it's (arguably) most infamous depiction of an amorous couple metamorphosed into an alligator. On and on it goes.

Interwoven within all the plant, animal, and machine imagery are notes, notations, tables, paragraphs, diagrams, and more. These additions are written in the spiraling script of what looks like an alphabetic language, something like Arabic by way of a spiral-obsessed, very bored, very determined cellmate. It's by turns disturbing and reviling, wondrous and charming, or insane and uncanny. The imagery makes just enough sense to make the reader want to make sense of it. It's a fever dream of apophenia — the human tendency to want to make sense of patterns — written into a "quirky encyclopedia" of an "extraterrestrial" world, as Grapheine puts it.

Most pointedly of all, the "Codex Seraphinianus" is basically just an art project published in 1981 by Italian artist Luigi Serafini.

A Rorschach test of imagination from artist Luigi Serafini

When flipping through the "Codex Seraphinianus," you might want to ask the author, "What were you thinking?" Surely, there must be some code — something to decipher. It's a revelation, perhaps, a cosmic secret bequeathed through a singular, worthy mortal vessel. It's like the Voynich Manuscript from the 15th century, similar in artistry and content, which professional codebreakers continue to try and crack as recently as a 2020 attempt by a German Egyptologist, as The Art Newspaper describes. It's like the "Codex Gigas," a 30-year-long mammoth endeavor from at least A.D. 1200 written by a single monastic author and containing magic spells, esoteric texts, and the largest medieval illustration of the Devil. It's like the "Urantia Book," the 2,000-page-long mashup of New Age celestial hierarchies and Jesus-as-alien mythos that spawned the actual Urantia University Institute. It's like beat poetry as pictures.

But actually... no. The difference here? The author is still alive, and we can just ask him. Speaking to Open Culture, Luigi Serafini, after whom the "Codex Seraphinianus" is named, says, "At the end of the day [it's] similar to the Rorschach inkblot test. You see what you want to see. You might think it's speaking to you, but it's just your imagination." Serafini is an architect and designer, too, and has also worked in movies. As the book's publisher Rizzoli states, the Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea in Milan dedicated an exhibition to him in 2007. Also? He's a fan of Franz Kafka.

A 'proto-blog' telling the story of telling meaning

Wired conducted an in-depth interview with Luigi Serafini in 2013. Serafini took several years to write the "Codex Seraphinianus" from his studio in Rome. To him, born in 1949, it was the "product of a generation that chose to connect and create a network, rather than kill each other in wars like their fathers did." He likened it to a "proto-blog" personally conveyed by readers, and said that he was "anticipating the net by sharing my work with as many people as possible." One of his goals was "to convey to the reader... the sensation that children feel in front of books they cannot yet understand," and that "the real challenge is to offer something completely new and different."

The internet did indeed popularize the mythos of the "Codex Seraphinianus." Serafini said: "The book took over his author, I ended up being just a go-between ... It's a book that speaks about crisis and about communication and it's quite apocalyptical, suited for the present times. Anything can happen inside the Codex, just like in the Internet."

In the end, the "Codex Seraphinianus" does what all art minimally does, genius or otherwise: It tells us about ourselves as we attempt to make sense of it. Like the original Italian publisher Alberto Manguel says on The World, "We have a tendency to believe that everything that surrounds us is an encoded language... We make sense of the world in order to survive in it."