What It Was Like Serving On The Timothy McVeigh Jury

One of the dead was described as a "back-seat quarterback." Others were givers, builders, musicians, and crafters. Some were very religious. A couple of the victims were described as determined, take-charge types. Others were said to be quiet, kind, or loving. They adored their families. Most had lots of friends. One woman loved to bake Christmas cookies. A few of the 168 people killed in the Oklahoma City bombing on April 19, 1995, were described as having an infectious enthusiasm.

Of the 19 children who were murdered, one toddler was nicknamed "Motormouth." Others were said to be good-natured and happy. One little guy was said to love "anything he wasn't supposed to mess with," according to the Oklahoma City Memorial Museum's page dedicated to those who died on that clear spring morning when a bomb ripped through the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City.

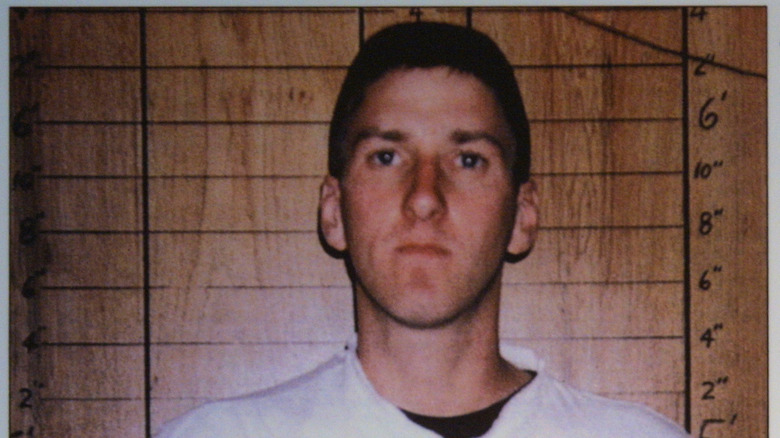

At the time it was the "worst act of homegrown terrorism in the nation's history," according to the FBI. But it didn't take long to find a suspect. In fact, by the time investigators followed the clues and tracked down the name Tim McVeigh, they learned he had been arrested just about an hour and a half after the bombing when a state trooper nabbed him 80 miles outside of Oklahoma City for driving his getaway car with no license plate and for having a concealed weapon.

Timothy McVeigh's trial was held in Denver

Timothy McVeigh was charged for the bombing on April 21, 1995, along with a co-conspirator named Terry Nichols, per the Denver Post. Both were federally indicted on Aug. 11 on 11 counts. Later a third man, Michael J. Fortier, was arrested on charges related to the crime, but the three men would be tried separately. McVeigh was up first.

McVeigh's charges included using a weapon of mass destruction to kill and destroy federal property, "using a truck bomb to kill people," and for "malicious destruction of federal property resulting in death." The other charges had to do with the eight federal law officers that died in the bombing, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

The trial was held in Denver instead of Oklahoma to help ensure they could find jurors who could be objective. According to the University of Missouri-Kansas School of Law's Famous Trials website, jury selection started for the McVeigh trial on March 31, 1997.

Once the jury was selected, the twelve members were mostly white and ranged in age from their 20s to their 70s, according to the Washington Post. They were seven men and five women including a grandmother, a teacher of learning-disabled kids, a landscaper, a Sears employee, A Vietnam veteran, a computer technician, an R.N., a maintenance worker, a government housing property manager, a young restaurant employee who'd just finished college, an engineer, and a computer programmer, per the Denver Post.

A juror said the testimony of the survivors and families was 'pretty overwhelming'

Two years after nearly 150 federal workers and 19 of their children were killed in the bombing, Timothy McVeigh's trial finally began on April 24, 1997. By then the FBI had volumes of evidence. The agency reported, "the Bureau had conducted more than 28,000 interviews, followed some 43,000 investigative leads, amassed three-and-a-half tons of evidence, and reviewed nearly a billion pieces of information."

Mike Leeper, a.k.a. juror number 5 in the McVeigh trial, told The Marshall Project in 2015 that due to the sheer amount of evidence some days were "incredibly tedious." He said since the jury wasn't allowed to take notes it was imperative they pay close attention because it wasn't clear what would be important when they deliberated.

Overall though, Leeper said, "I remember the graphicness of the testimony of the survivors and the families, and that was pretty overwhelming. Just a sadness of totally innocent people who did nothing wrong on that day. There were so many."

Leeper also told The Marshall Project that he was very impressed with the way Judge Richard P. Matsch handled the courtroom. He said the judge was a "sharp cookie."

One member of the jury said the evidence 'hit home' and proved McVeigh's guilt

The jurors started deliberation on May 30, 1997, after more than a month of hearing evidence and testimony, according to the Washington Post. The jury was, as is usual, ordered to avoid any media coverage of the trial and they were not allowed to be alone together outside of the courtroom, that is until it was time for deliberations. Leeper told The Marshall Project that it was beneficial to have a "wide variety of people" on the jury. Some remembered things the others didn't.

According to what juror Ruth Meier told CNN, the jury dedicated itself to looking over the evidence with a fine-tooth comb.

"We went over the evidence piece by piece," Meier said. "We read papers and reread papers. We handled the evidence, and the more we handled it and the more we saw it, the more sure we were we had to come up with a guilty plea."

Once the jury got together and was able to get their hands on the evidence, they had no doubt of McVeigh's guilt, according to what another juror, Roger Brown, told CNN.

He said, "We were overwhelmed with the evidence. That was the most shocking thing to me. It was, 'Yeah, he's guilty.' It just hit home."

The jury found Timothy McVeigh guilty on all charges

According to the Washington Post, the jury in the Timothy McVeigh trial was presented with the prosecution's story that McVeigh's fury against the federal government — in part for their involvement in stand-offs in Waco and in Ruby Ridge, both of which ended in federal agents killing rebellious civilians — motivated him to take revenge and blow up a federal building.

The defense argued that McVeigh's opinions about the federal government, as displayed in his writings, didn't make him a killer. They tried to portray McVeigh as a scapegoat for federal agents who were desperate to solve the case, manipulating the evidence and witnesses to wrongly prove McVeigh carried out the bombing, the Washington Post reported.

Prosecutor Larry Mackey spent more than three hours recapping the case in his closing arguments, saying to the jurors, "What you learn from all this evidence is that Timothy McVeigh either bombed the Murrah building and killed all those people," said Mackey, "or he is the unluckiest man in the world," per The Washington Post.

The jury deliberated for 23-and-a-half hours over four days. On June 2, 1997, they came back with a guilty verdict on all 11 counts.

The jury sentenced McVeigh to death

The jury found McVeigh guilty of the mass murder of 168 people but the they had one more job to do in the case. They had to decide whether his crimes were enough to warrant the death penalty. According to the Washington Post, the jury had to decide whether seven aggravating factors were in play in McVeigh's bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.

Those factors included whether he intended to kill people, whether he pre-meditated or planned the crime, whether he created a "grave risk to others with reckless regard for their lives," whether his actions caused severe loss for the victim's families, and whether he committed crimes against federal law officials, per the Washington Post.

The McVeigh jury spent 11 hours over two days deliberating about whether he should get the death sentence. Finally they agreed unanimously that McVeigh's bombing in Oklahoma City checked all of those boxes and he was sentenced to death on June 13, 1997

Years later, McVeigh agreed to be interviewed by two authors for their book about McVeigh and the bombing called, "American Terrorist: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing." According to ABC News, McVeigh admitted publicly to the bombing for the first time in those interviews, and said he had no regrets nor any sympathy for the people he killed or their families. McVeigh died by lethal injection on June 11, 2001.