The Ten Plagues Of Egypt Explained

One of the most famous stories of the Old Testament is how God, through the prophet Moses, liberated the Hebrews from enslavement in Egypt by inflicting 10 calamities upon the land. This story, one of the most dramatic in Judeo-Christian traditions, is the centerpiece of Judaism's seven-day holiday of Passover which, as described by Britannica, celebrates the Hebrews' freedom from bondage. Passover is one of the most important holidays in modern Judaism.

Christianity too has been deeply influenced by the Ten Plagues of Egypt narrative. The story has been used as moral narrative for the struggle to overcome oppression and slavery. Its overarching themes of freedom and justice have resonated through the millennia. Throughout this time, there has been continual debate of the plagues with some seeking to prove that they were real events while others look to the story as a unifying moral tale that united a people. This is the Ten Plagues of Egypt explained.

The traditional account of the Ten Plagues of Egypt

The traditional account of the plagues is told in the Old Testament in the book of Exodus. The story begins with the Hebrews (sometimes Israelites) migrating to Egypt due to famine. The Hebrews originally prospered, but eventually they were enslaved by the Egyptians. Then, during the undated reign of an unnamed pharaoh, the prophet Moses entered the story.

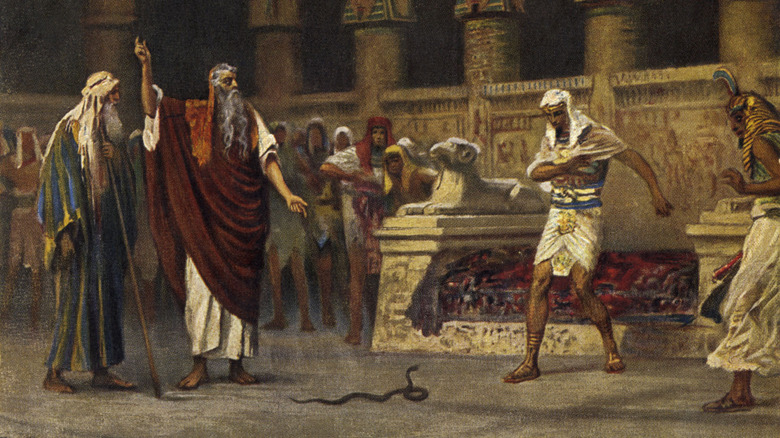

Moses was commanded by God to act as his prophet and free the Israelites. Exodus 7 quotes God, "And I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and multiply my signs and my wonders in the land of Egypt. But Pharaoh shall not hearken unto you, that I may lay my hand upon Egypt, and bring forth mine armies, and my people the children of Israel, out of the land of Egypt by great judgments. And the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I stretch forth mine hand upon Egypt, and bring out the children of Israel from among them."

Moses, as commanded by God, demanded the release of the enslaved Israelites with his companion Aaron, who acted as Moses' speaker. The pharaoh, as predicted, refused even though God turned Aaron's rod to a snake. As a result, God inflicted 10 plagues upon Egypt, called the maggafeh in Hebrew, which culminated in the slaying of every firstborn Egyptian son. This last plague broke the pharaoh's will and he freed the Hebrews. It is a great story, but people throughout history have asked whether it is true.

How much of the traditional account of the Ten Plagues of Egypt is true?

Any reported findings of proof of the Exodus are highly speculative, and most likely it did not happen as a dramatic historical event. Rabbi David Wolpe was quoted by the Los Angeles Times as saying to his congregants, "The truth is that virtually every modern archeologist who has investigated the story of the Exodus, with very few exceptions, agrees that the way the Bible describes the Exodus is not the way it happened, if it happened at all."

However, it is likely that a small group of people in Egypt migrated to Canaan. In trying bolster claims of archaeological evidence of the Exodus, the Biblical Archaeological Society cites findings, but each is based on speculation. The paper "Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective" emphasizes that there are hundreds of books devoted to the subject of proving the historicity of Biblical events. In the end, the authors offer that there was probably some form of the Exodus forming an historic kernel of truth, but not as written in the Old Testament. There is also fierce debate as to when it occurred, with most scholars saying either the 13th century or 15th century B.C.

This of course doesn't prevent scholars from trying to show how the plagues were plausible through mental gymnastics. Let's explore the Ten Plagues of Egypt individually, see what is known about them, and look at how scholars have tried to logically explain what happened.

Plague one: The Nile turns to blood

As described in Exodus 7, Moses let loose the first plague after Aaron struck his rod in the Nile, which caused it and all waters tied to it to turn to blood. This water grew putrid, becoming undrinkable and killing off all the fish. As noted by the Catholic Encyclopedia, the common consensus was that it didn't literally turn into blood but was instead fouled by some other substance.

LiveScience reports that some scholars have speculated that this condition may have been red tide. This occurs when water conditions allow red algae to proliferate in such great numbers that it can turn the color of water crimson. It is also toxic to some fish and shellfish. This phenomenon is well known in recent years, with Ecowatch reporting one large outbreak on both coasts of Florida in 2018.

Another theory that has been offered has to do with the fallout from a volcanic eruption on the Aegean island of Santorini around the year 1600 B.C. Time reports that some have advanced the notion that volcanic dust including the red mineral cinnabar caused the disaster.

Plague two: Lots and lots of frogs

The second plague were frogs. Lots of them. As quoted from Exodus 8, "And the river shall bring forth frogs abundantly, which shall go up and come into thine house, and into thy bedchamber, and upon thy bed, and into the house of thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thine ovens, and into thy kneading troughs."

So what's the deal with this one? Frogs seem more annoying than plague-like. While it is never clearly explained why frogs would be a plague, those who push the red-tide theory of the first plague link the second plague to the first. As reported by the New York Times, frogs could have rampantly bred in a river devoid of fish. However, they would have been driven out of the water by lack of oxygen.

Meanwhile, Time explains that if the volcano theory happened and the water was fouled by ash, it would have been so acidic that it would have driven the frogs out of the water. LiveScience also reports that there have been historical instances of mass movement of frogs, including several occurrences of a phenomena in which frogs rain down from the sky.

In any case, the pharaoh temporarily agreed to release the Hebrews. So God killed all the frogs, leaving lots of amphibian corpses. The pharaoh, however, went back on his word, and this set up the third plague.

Plague three: Lots of people scratching with lice

The third plague is somewhat nebulous. Exodus 8 tells how Aaron, at the behest of Moses, struck the ground with his rod, which turned the dust to lice. In its analysis of the plagues, the paper "Origin of the Old Testament Plagues: Explications and Implications" points out that the Hebrew word kinim has usually been translated to mean gnats, mosquitoes, or lice. Basically small biting insects. In this theory, atmospheric warming created warmer swamp-like conditions that these insects thrived in.

LiveScience proposes that all the dead frogs from the end of the second plague certainly would have led to an increase in insect activity. The New York Times reports that this could have been culicoides, small biting insects that lays their eggs in the dust, and whose larvae feast on corpses, such as dead frogs.

The pharaoh, of course, didn't get the hint, so it became obvious that the plagues needed to be intensified.

Plague four: Wild beasts or just more bugs?

The fourth plague is even murkier than the third. The King James version of Exodus translates this plague as one of flies. However, Bible Review notes that other translations have this plague as wild animals. The Hebrew term used in the Old Testament, arov, means "mixture," so it has been hard to pinpoint exactly what this plague was.

In fact, the Haggadah, the Jewish text for the Passover ritual sedar, has often been decorated with fierce beasts to depict the fourth plague. This seems to be due to translation issues over time, with debate over whether the term meant a mixture of wild animals or a mixture of insects. It is perhaps more likely that this plague was indeed insects of some kind, since it is hard to imagine lions, tigers, and wolves invading the pharaoh's land en masse.

If the fourth plague is interpreted as flies, it fits more tightly with the speculative framework of the Ten Plagues of Egypt being linked to scientific climate change. As analyzed in "Origin of the Old Testament Plagues: Explications and Implications," which promotes a climate warming theory, "Biting flies, having hatched in soil heavily polluted with animal urine and feces, also would have become abundant with warming weather." Indeed, flies would have easily bred in a land strewn with frog corpses.

The pharaoh at first agreed to let the Israelites go to the wilderness to pray for three days if Moses ended the plague. But he went back on his word.

Plague five: A disease that killed off livestock

The fifth plague, as written in Exodus 9, was an infectious disease that killed livestock, specifically Egyptian livestock, not Hebrew livestock. The King James version reads, "Behold, the hand of the Lord is upon thy cattle which is in the field, upon the horses, upon the asses, upon the camels, upon the oxen, and upon the sheep: there shall be a very grievous murrain."

This particular plague has many types of historically comparable events. LiveScience notes that rinderpest is an infectious disease that has afflicted cattle for centuries. The New York Times reports that African horse sickness and Bluetongue are two diseases that afflict only hooved animals, and that are spread by culicoides. These infectious diseases could have been spread by the insects of the fourth plague.

Just why the disease spared all the Israelite livestock is not easily explained, though one theory is that their livestock may have been situated well away from the insects that were the disease vector.

Plague six: A really nasty skin disease

For the sixth plague, it seemed like God wanted to get more personal. As quoted from Exodus 9: "And the Lord said unto Moses and unto Aaron, Take to you handfuls of ashes of the furnace, and let Moses sprinkle it toward the heaven in the sight of Pharaoh. And it shall become small dust in all the land of Egypt, and shall be a boil breaking forth with blains [skin sores] upon man, and upon beast, throughout all the land of Egypt."

Ouch. In trying to figure out a potential cause of this plague, "Origin of the Old Testament Plagues: Explications and Implications" links causality from the insect pests of the fourth and fifth plague and speculates that fly larvae could perhaps have burrowed into the skin of animals and humans to cause such horrid swelling. These researchers felt that the Tumbu fly larvae could be responsible, since these grubs have been known to emerge from human legs and buttocks. This would explain why the pharaoh's "...magicians could not stand before Moses because of the boils; for the boil was upon the magicians, and upon all the Egyptians."

The paper "Environmental and Medical Aspects Related to the Sixth Plague of Egypt" takes a different tack, relating to the mention of ashes and dust, and proposing that the boils were the result of environmental air pollution. Regardless of the cause, the pharaoh did not seem to be bothered by the boils, so he did not free the Hebrews.

Plague seven: Fiery hailstorm

For the seventh plague, God started getting even more dramatic. This plague, as described in Exodus 9, consisted of fiery hail storms. The authors of "Origin of the Old Testament Plagues: Explications and Implications," propose that this was a result of an El Niño-Southern Oscillation superstorm.

Another explanation goes back to the theory of a volcanic explosion in Santorini. As reported by Time, such a volcanic eruption may have disrupted weather patterns, perhaps causing storms. This seems to be the only plausible kind of scientific explanation for a storm of such intensity. According to tradition, the result was calamitous. Crops were destroyed en masse and there was a threat of famine. As the story goes, the pharaoh repented, but only temporarily.

It is also notable that biblical scholars found that the seventh plague in the text is treated different from the other plagues. The article "The Significance of the Seventh Plague" notes that there is more text devoted to this plague than any throughout the Hebrew Bible. This may be because of the significance of the number seven in ancient Middle Eastern religions.

Plague eight: Locusts

When Moses and Aaron returned to the pharaoh, they issued a new threat. They went back to the old standby of insects, specifically locusts. As quoted in Exodus 10: "And they [locusts] shall cover the face of the earth, that one cannot be able to see the earth: and they shall eat the residue of that which is escaped, which remaineth unto you from the hail, and shall eat every tree which groweth for you out of the field..."

Some have speculated that the moist and humid conditions caused by the earlier plagues were the ideal conditions for locusts to thrive (via Time). Siro Trevisanato, a Canadian scientist who supports the volcanic explosion theory and wrote "The Plagues of Egypt: Archaeology, History and Science Look at the Bible," was interviewed by the Telegraph. He was quoted as saying, "The ash fallout caused weather anomalies, which translates into higher precipitations, higher humidity.And that's exactly what fosters the presence of the locusts."

As related by Exodus, the pharaoh again repented and begged Moses to get rid of the locusts. This was done by a mighty divine wind. Then, predictably, the pharaoh reneged on his promise.

Plague nine: Darkness for three days

By now, it was clear that the Egyptian pharaoh wasn't getting the hint. So this time God wanted to do something completely unnatural. Exodus 10 recounts: "And the Lord said unto Moses, Stretch out thine hand toward heaven, that there may be darkness over the land of Egypt, even darkness which may be felt." This darkness lasted for three days, and caused all the Egyptians to stay home except the Israelites, who had lights within their own houses.

One explanation of this plague is offered by the Jewish Encyclopedia, which says that a south or southwest wind may have blown an intense sandstorm into Egypt, thus darkening it with very fine particulates. The volcanic explosion theory, as reported by LiveScience, could of course also have caused prolonged darkness. Alternatively, the tenth plague could have been a solar eclipse, although there is no recorded solar eclipse that has lasted for three days.

According to Exodus, this plague did have some impact, since the pharaoh was willing to let the Hebrews go free. But he told Moses and Aaron that they would need to leave their flocks behind. This was unacceptable to Moses. So the pharaoh, now insulted, kicked Moses and Aaron out and threatened to execute them if they dared come back. This led God to tell Moses that he was going to smite the Egyptians with one last plague that would do the job.

Plague ten: Killing of firstborn sons

The tenth plague is the selective killing of all Egyptian firstborn sons and firstborn cattle. To prevent the Israelites from being slain, God told them to smear lamb's blood upon their doorways so it would pass over them — thus the holiday of Passover was born.

This plague is the hardest one for experts to offer rational explanations for. The Biomedical Scientist reports that archaeologists have long offered the explanation of a fungal wheat infestation for the deaths of babies and livestock. This, however, does not really explain the selective killing of the tenth plague. Another possible explanation is offered in "Origin of the Old Testament Plagues: Explications and Implications," which suggests that the water puddles and vegetation growth from the seventh plague would have caused a e proliferation of mosquitoes, which attracted birds, and the birds passed on deadly diseases to the ancient Egyptians. This explanation strains credulity for the same reason — although it offers some idea of why vulnerable young children and animals may have died, it does not satisfactorily explain the selective killing.

However, as religious tradition holds, this plague did the trick and the Hebrews were freed from slavery.

Much of the scientific proof of the Ten Plagues of Egypt is speculative at best, but that is beside the point. The Ten Plagues of Egypt are a powerful spiritual statement. The theme of the power of God to liberate both physically and morally holds a powerful grip on the spirit and imagination.