The Tragic Real-Life Story Of The Bronte Sisters

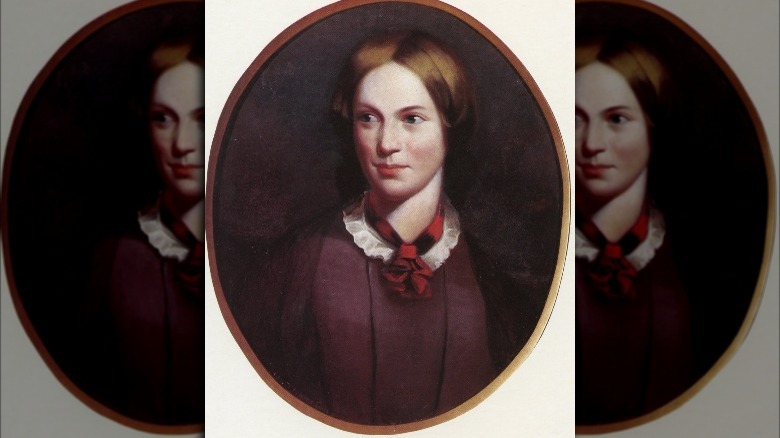

When people are asked to pick some of the most tragic characters in all of literary history, chances are pretty good that many will settle on the Brontë sisters. The three siblings who made their mark as authors — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne — are now well known for their novels, which include beloved classics like "Jane Eyre" and "Wuthering Heights." Few other 19th century authors can lay claim to the sort of modern success and name recognition now enjoyed by the Brontës.

But, during their lifetimes, they dealt with a wide and exhausting range of misfortunes. These included not only a number of family deaths that haunted them from nearly the beginnings of their lives, but also financial worries, romantic woes, and the treacherous sexism of 19th century Britain. That's not even mentioning the difficulties they encountered when trying to get their groundbreaking novels published in a growing literature industry that was at least as difficult to navigate then as it is today.

And, unlike the calamities that befell their fictional characters, all of the well-documented suffering of the Brontës really happened. From disease, to artistic rejection, to death itself, it may sometimes seem like all three experienced some of the worst the 19th century had to offer. That may not necessarily be true, but neither is their story all sunshine and rainbows. This is the tragic real-life story of the Brontë sisters.

Their mother died when the Brontë sisters were still young

While much is made of the three writerly Brontë sisters, as well as the occasional feature on their wayward brother or long-lived father, many forget to talk about their mother. Maria Branwell, who married Patrick Brontë and gave birth to their six children, is often referred to obliquely as "Mrs. Brontë " or even forgotten entirely.

But Maria Branwell Brontë has her own story, much of it compelling and quite tragic in its own right. According to the Bronte Parsonage Museum, she was born in 1783 and her early life was also marred by a spate of family deaths, including those of both her mother and father within the space of just four years. Left effectively on her own, the young Maria joined her aunt as an assistant housekeeper. She eventually met a curate named Patrick Brontë and married him in 1812.

After that, quite a few accounts pare her life down to the six children she produced, beginning with eldest child Maria in 1814 and ending with Anne in 1820. She died in September 1821 of what may well have been a tortuous bout with uterine cancer, when all of her children were still quite young. But many forget that Maria was also fully human, a woman who was reportedly outgoing, witty, and educated. She was compelling in a way that must have drawn not only her husband Patrick to her side, but those who became her friends during her short life.

School literally killed some of their siblings

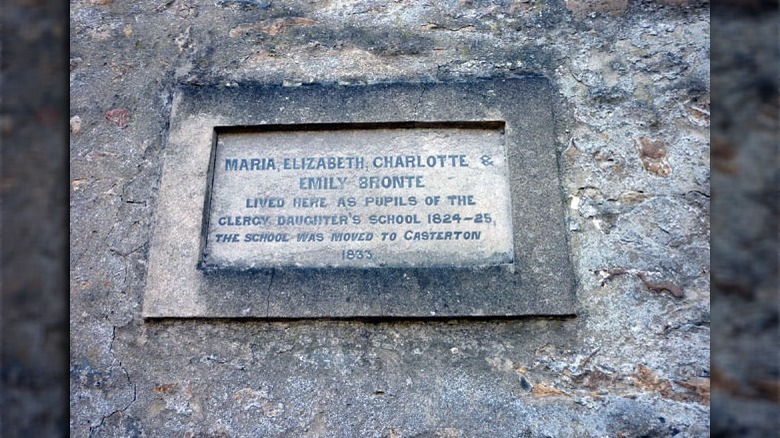

In 1823, some three years after their mother's death, a few of the Brontë siblings were sent to Crofton Hall, a boarding school for girls (via the Brontë Parsonage Museum). This would have been a big step for the attending siblings, eldest daughters Maria and Elizabeth, but the expense proved to be too much for their father. Eventually, they transferred to a more affordable institution, the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge, where Charlotte and Emily soon joined them.

Education could be a significant boost up in the highly stratified world of 19th century England, allowing girls of the middling sort a chance to earn their own living — albeit in a limited set of circumstances, as the sisters would discover later on in their lives. But, as the British Library reports, this opportunity would turn into disaster in short order. In 1825, about a year after the girls first enrolled at Cowan Bridge, typhoid fever ripped through the student population. Maria and Elizabeth became sick, were sent home, and died of what may have been in short order. Charlotte and Emily also returned home, but seemingly escaped any disease.

However, the harshness of the school's conditions — which some allege contributed to poor nutrition and greater susceptibility to disease for students — never quite left the surviving sisters. Charlotte almost certainly drew on their experiences at Cowan Bridge for the notoriously cruel though fictional Lowood School in her later novel, "Jane Eyre."

The Brontë sisters were in a socially agonizing situation

In Britain of the 19th century, class hierarchy was a pervasive way of life. Per the British Library, there traditionally wasn't much movement between classes, but the era in which the Brontës grew up saw more social mobility. However, it was all predicated on punishing conditions, like intense work, paltry pay, and moral judgements that assumed poor people were lazy rather than unfortunate. There was also quite a bit of fretting over whether or not women should work, with many taking the view that women of a certain social class couldn't both have a job and remain "proper."

Yet, as the Brontës discovered, sometimes you just needed to make money. While they didn't deal with extreme poverty like some sources might have you believe, they weren't rich either, says the Brontë Parsonage Museum. Given that their father's income wasn't enough to ensure a comfortable existence for all of his surviving daughters, they had to work.

This landed them in socially ambiguous and oftentimes isolating roles like teachers and governesses. The British Library notes that governesses, who worked like in-home tutors for rich families, were in odd situations. They were typically "beneath" a family in terms of class, yet "above" the other servants, meaning that they could live lonely existences. That, combined with paltry salaries, made work as a governess often unstable. Both Charlotte and Anne's experiences as governesses informed their later work, like "Jane Eyre" and Anne's "Agnes Grey."

Charlotte Brontë kind of became a stalker

As she grew into adulthood, eldest surviving sister Charlotte surely understood that she needed to earn a living for herself. For many women of the Brontës' situation, that meant teaching. And, for Charlotte, that also meant she eventually turned into something of a stalker.

According to Brain Pickings, it all began in 1842, when Charlotte and Emily traveled to Brussels, Belgium to teach at a school there. A family death caused them to travel back to England, but Charlotte later returned alone to Brussels and began her association with Constantin Héger, the school's founder. Héger tutored Charlotte in French, leading to some close associations, but he was also a married family man who apparently wasn't interested in stepping over the line.

Charlotte eventually went back to Britain for good, but began sending Héger intense letters, with phrases like "you showed a little interest in me in days gone by ... I cling to the preservation of this little interest" and "I will not resign myself to the total loss of my master's friendship" (via British Library). Some may think this romantic, but Héger and his family were creeped out. He eventually stopped responding to Charlotte's letters and his wife, Zoe, stepped in to pump the brakes on the younger woman's obsession. Yet, Zoe also preserved the letters that her husband threw away, perhaps sensing that the world needed to know about this side of Charlotte Brontë, too.

Anne Brontë had a miserable time as a governess

The youngest Brontë sister, Anne, was also obliged to make a living like her other siblings. And, as the British Library notes, she may have been especially quiet and pliant, having lived in a household full of big and perhaps occasionally overbearing personalities. So, when she became a governess for the Ingham and Robinson households, she was apparently primed to have a pretty terrible experience.

We don't have a clear picture of what Anne's real-life experiences as an in-home educator were like but, if they're anything like what's depicted in her first novel, "Agnes Grey," it was downright hellish. Per The Guardian, the incidents and characters in the novel include a sociopathic young man named Tom Bloomfield, who gets grim satisfaction out of torturing small birds. At one point, Agnes, the titular governess character, kills a nest of baby birds so they won't have to suffer Tom's ministrations. When someone asked Charlotte if this really happened to Anne, she didn't confirm or deny it, but did say that being a governess opened one's eyes to the innate corruption that could lie in a person's seemingly lovely heart.

The Brontës may have been drinking contaminated water

While much is made of the social and economic conditions that shaped the lives of the Brontës, it's easy to forget that they were also flesh and blood human beings who lived in a very real physical world. And that world, it seems, sometimes had a serious effect on their health in potentially dramatic ways.

It's generally accepted that the sisters had a hard time of things, health-wise, given that all of the children died of various afflictions before their own father's death in 1861 at the rather advanced age of 84 (via Brontë Parsonage Museum). But, beyond some vague talk about how they might have contracted communicable diseases like tuberculosis, not many sources get into the nitty-gritty of why so many young adults would have succumbed in such relatively quick succession.

It could be, as LitHub notes, that the source of the illness had to do with something as mundane as infrastructure. Haworth was plagued by issues with sewage, with fetid cesspits alarmingly close to sources of drinking water. Moreover, the parsonage was right next to the local graveyard, which was situated in such a manner that all of the dead inhabitants and any pathogens they contained could have also been leaching into the local water supply.

Charlotte Brontë seemed all too ready to diss Anne

Poor Anne Brontë. While everyone's talking about Emily and "Wuthering Heights," or else gushing about Charlotte's reputation as an obsessive letter writer and author of the beloved "Jane Eyre," youngest sister Anne is often ignored. Some readers may even forget that she ever existed, much less wrote two novels, "Agnes Grey" and "The Tenant of Wildfell Hall" (one more than Emily, for what that's worth). Yet, as much as that might sting for fans of Anne, the woman herself may have had to deal with similar snubs in her very own home.

Charlotte seems to have been especially ready to give what she thought was the unvarnished truth of her sister. According to the BBC, she painted a picture of Anne as a real downer, not to mention a less talented writer who was more focused on her exit from the world than actually living in it. Yet author Samantha Ellis, speaking to the BBC, argues that Anne was actually a pretty interesting figure who may have been the most groundbreaking member of the writing trio — and whose work was suppressed by none other than Charlotte.

It doesn't help that, as The Guardian reports, "Agnes Grey" was published after Charlotte's "Jane Eyre" and may have seemed like a more realistic, less compromising, and therefore less marketable governess novel, compared to the dark, swooning romance of "Jane Eyre."

Branwell Brontë struggled with substance abuse

While the Brontë sisters were dealing with work troubles, systemic sexism, and the horrors of getting a novel published, they also had to manage the ups and downs of their perpetually troubled brother, Branwell.

Branwell's problems seemed to reach their peak just when the sisters were finally starting to see their own artistic ambitions come to fruition. That led to his reputation as the ne'er-do-well of the family, says The Guardian, but that image flattens Branwell Brontë's complicated story. He appears to have been as intensely creative as his sisters, participating in early childhood storytelling and artistic works. Branwell even ventured into painting as a semi-professional, but alcohol and substance issues stymied much of his work and contributed to his early death aged just 31.

Branwell also appears to have had an affair with a married woman that shocked not only his sisters, but many others outside of the family, as Historia reports. That woman was Lydia Robinson, whose son was being tutored by Branwell (becoming in-home educators was apparently the Brontës' standard fallback plan). An author and friend of Charlotte, Elizabeth Gaskell, actually included the claim in her biography of Charlotte. And though she didn't name Lydia, it was enough for Mrs. Robinson's lawyers to threaten Gaskell with libel and get the claims removed.

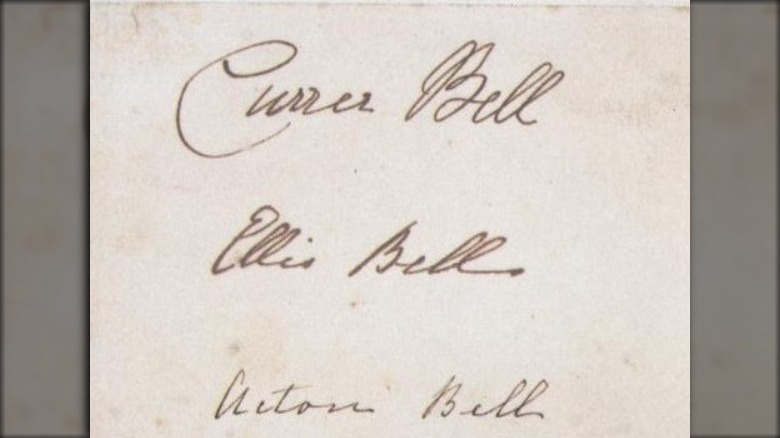

The Brontë sisters had to hide their gender

To finally publish their works, the Brontë sisters landed on a plan that was forced to acknowledge the rampant sexism of their day. They had to conceal their identities largely because they recognized their works went against many of the accepted norms for female writers of their day, who were expected to be more domestic and anodyne. Otherwise, it would be nearly impossible for publishers to accept the sisters' novels. As The Conversation notes, this means that the publishers who first worked with the Brontës barely knew anything about their mysterious but, soon enough, ultra-popular clients. The sisters first communicated and published under the names Acton, Currer, and Ellis Bell (Anne, Charlotte, and Emily, respectively).

When it came time for the sisters to reveal themselves as women, the three made their way to London, where Charlotte bluntly told publishers, "We are three sisters." The novels were subsequently reevaluated by some as "coarse" and the writers "nearly unsexed." Longreads reports that one reviewer, G.H. Lewes, who had previously issued glowing judgements of Charlotte's work turned his back on her completely. In The Edinburgh Review, he whined that women had no place as writers, arguing that "the grand function of woman ... is, and ever must be, Maternity." In short, he believed that Charlotte was better off quietly fading into motherhood, though "Currer Bell" had previously been a brilliant literary mind. Charlotte was, naturally enough, incensed at the words of her turncoat "friend."

Anne and Emily Brontë's deaths were traumatic for Charlotte

When talking about the tragedy of the Brontës, it's practically impossible to avoid the specter of death. Their mother died early on in their lives, followed only a few years later by their eldest sisters. Branwell, their only brother, died in his early thirties after a long struggle with both substance abuse and finding his place in the world. But, for many, some of the most tragic deaths in the Brontë tale are those of Anne and Emily.

Per Britannica, Emily's death in December 1848 came after a lingering, painful illness that accelerated after her only novel, "Wuthering Heights," was published. It was an end that, according to "The Brontës," continued to haunt Charlotte for many years afterward. She once wrote that "I cannot forget Emily's death-day ... it was very terrible." Anne died only the next year, also succumbing to tuberculosis in May 1849. Her end was somewhat more peaceful, says "The Brontës," with Anne accepting her coming demise and dying so quietly that no one but those at her bedside knew when it happened.

According to the Independent, tuberculosis, a highly contagious respiratory disease, could have been easily shared amongst the family. Prior to the spate of deaths, they all lived together in relatively close quarters at their father's parsonage in Haworth. Branwell and Emily both died there, while Anne's passing came farther away in Scarborough. Once again, Charlotte was devastated by her sibling's death.

Charlotte Brontë also had a difficult death

After Anne's death in 1849, Charlotte was left as the only surviving Brontë child. And eventually, unlike any of her siblings before, she got married. This wasn't the first time that Charlotte had come close to matrimony. Per History, she declined a marriage proposal a decade earlier, writing to the Reverend Henry Nussey that she was too "eccentric" for marriage. Shortly thereafter, she traveled to Brussels and began her ill-fated infatuation with Constantin Héger. It wasn't until after the death of Anne and the illness of her father that Charlotte finally agreed to marry Arthur Bell Nichols, her father's curate (a kind of assistant priest).

Though Charlotte initially seemed to do well as a married woman, she was eventually struck by illness. In "The Brontes: Life and Letters," she was struck with intense and unrelenting nausea, to the point where she could barely stand to look at food. She grew increasingly weak and, after months of suffering, died in 1855.

For years, many wondered what could have killed Charlotte. Given that she wasn't obviously suffering from a respiratory illness, it likely wasn't the tuberculosis that killed so many other members of her family. According to the journal Clinical Nutrition, it's most likely that she suffered from a condition known as hyperemesis gravidarum, or severe morning sickness. That could have been further complicated by "refeeding syndrome," a dangerous change in electrolytes that can happen when a previously starving person begins to eat again.