The History Of The Most Sacred Rocks In The World

It seems like no matter what problems humankind faces — whether it's the stresses of a 21st-century world or wondering how well your sharpened stick was going to do against all those teeth — there's something that unites us across the history of humanity: The desire to believe in something larger. And it turns out that humankind has been believing in things we can't always see for a long time.

According to the University of Oslo, humans were performing ceremonies of ritual worship 70,000 years ago. University research teams came to the shocking realization when they found evidence of ritualized belief in an area of Botswana's Kalahari Desert called the Tsodilo Hills, which was already well-known as the site of thousands of cave paintings. A little more exploring revealed there's something else there, too: a sacred cave, and a rock that bore a striking resemblance to a python.

The rock, which is 20 feet long and about 6.5 feet tall, has a unique pattern that looks like snakeskin in the daylight and seems to move in flickering firelight. The site was surrounded by over 13,000 artifacts, including a lot of spearheads that seem to have been left as offerings.

The idea of a rock at the heart of sacred ceremonies and worship isn't a strange one, and throughout history, humankind has assigned powerful thoughts, meaning, and prayer to a number of sacred stones. Big or small, their power to inspire is undeniable.

"Everyone thought Tamanowas Rock would be there forever."

It was in the early 1990s that the people of the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe realized their ancient, sacred Tamanowas Rock wasn't guaranteed to be there for the next generation.

It had stood watch over Washington State's Jefferson County for a long time: Once, it was used by hunters and lookouts to keep watch for approaching mastodons, but it was around long before even that. Made from the lava that poured from the Earth around 43 million years ago, the rock has been used as a lookout and a shelter from floodwaters and is considered sacred to the S'Klallam and the Chimacum (who were folded into the S'Klallam as their population declined).

Tamanowas Rock towers around 150 feet above the surrounding forests, and the surface of the rock is pockmarked with caves and crevices that were once used for spiritual vision quests. It was considered a sacred place that a person would go to in order to meet their guardian spirit, and the S'Klallam still leave offerings of thanks at the rock, acknowledging generations of guidance.

The area is now protected by the Tamanowas Rock Sanctuary and the Jefferson Land Trust, but it was nearly gone forever. It took two decades of negotiations and purchases to save the land from real estate developers and make sure it was safely in the hands of those who have loved it for thousands of years.

The rocks joined in a sacred union

Standing off the coast of Japan near the town of Futami is, at first glance, an odd sight. Two rocks rise out of the water, and they're tied together with a rope.

That's not all they're connected with, because according to Japan-Guide.com, the rope is a shimenawa rope, woven with rice straw and replaced three times a year in a sacred Shinto ceremony. It's meant to represent not just a union but also the divide between the earthly realm and the spiritual one. Atlas Obscura says the two rocks — with their symbolic connection — represent "paired dualities," with the larger rock representing a husband and the smaller rock seen as the wife. They're seen as the embodiment of a holy union between two sacred entities, one that ultimately went on to create all the Shinto spirits.

The rock formation known as Meoto Iwa stands just near the Futami-Okitama Shrine; those hoping to bring people back into their lives commonly leave frog sculptures or tokens there.

The Foundation Stone sacred to many

The history of the building known as the Dome of the Rock is insanely complex, but here are the basics (via Reuters): It was built in 691, and according to Muslim tradition, the Foundation Stone marks the place where the Prophet Muhammad was standing when he rose into heaven.

Here's where things get complicated.

It's also a sacred spot in other religions. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Judaism says the Foundation Stone was the source of the dust used to create the world's first man, Adam, and it's also where Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his own son at God's behest. Christians, on the other hand, believe it's where Christ went head-to-head with the money changers, and it's just a short distance away from where he was crucified.

Beliefs involving the Foundation Stone are just as extensive, so here's one: According to the Texas Jewish Post, Jewish belief says the Foundation Stone holds all the powers of the world. What does that mean? Rabbi Fried gives just one example: All plants are said to grow on the Foundation Stone, which then acts as a conduit that allows life to grow elsewhere.

The entire area was settled around 4,000 years ago, and since then, it's been controlled by the Canaanites, Nebuchadnezzar and the Assyrians, the Greeks, Romans, and the Persians, the Byzantines and the Ottomans, and even the Crusaders. (In 1099, the Foundation Stone was turned into the foundation of stables for the horses of the Knights Templar.)

Scotland's most mysterious standing stones

When it comes to standing stones, Stonehenge gets all the attention. But according to the BBC, Scotland's Callanish (pictured) and Stenness standing stones are even older than Stonehenge — and were just as sacred.

That's the running theory, at least. Stenness and Callanish both date back to around 5,000 years ago, and this was about the time people were shifting from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle into an agricultural one. It was also the time they started building monuments, and that's where stone circles come in.

The theory that both of these stone circles served a dual purpose as monuments to the dead and observatories went back to Alexander Thom's work in the 1930s, but it was only in 2016 that researchers from the University of Adelaide confirmed that yes, the stones were aligned with the most extreme positions of the Sun and the Moon.

It wasn't just a way to keep track of the seasons, though. Researchers believe these stones were an acknowledgement of the builders' place in the universe and were a nod to the idea that the land and nature were much more powerful than any person could hope to be. Other archaeologists and historians lean even more heavily into the idea that they were built as monuments to the dead, and the two are very connected. University of Adelaide's Gail Higginbottom explains: "There was still a sympathetic magic. They believed that if they set up these monuments, they [were] connecting death and [nature]."

Vishapakar, the Dragon Stones

Go far enough back into history, and things get a little fuzzy. Take the so-called Dragon Stones that are found across what's now Armenia. These basalt standing stones date to sometime in the Bronze Age, and around 150 remain. There are a few different versions: Some are carved to look like fish, some are cows or bulls, and others have both animals.

While the Eastern Partnership Culture Programme says it's not 100% clear just what they were, archaeologists have been able to make some educated guesses based around the fact that most of the stones were found in areas that have a connection to water sources and burial grounds.

One of the ongoing theories is that the stones mark the location of sacred sites used to perform ritual sacrifices. Armenian highland and Philology scholar Armen Petrosyan, PhD, suggests the bull represents the thunder god of ancient creation stories, while the fish represents the adversarial serpent. Other theories suggest the carved animals represent the guardians of the ancient civilization's water sources, and another says they're meant to symbolize the god of death and rebirth, along with the goddess of love and fertility. Whatever they truly meant to those who created the 150+ standing stones, one thing that hasn't been questioned is their importance.

Australia's most iconic monolith is deeply connected to Aboriginal beliefs

No matter where they're from, it seems as though indigenous peoples have historically gotten the short end of the stick — and that's absolutely true for Australia's Aboriginal peoples. The chronic lack of respect they've been shown is nowhere more evident than around Uluru, the sandstone rock that National Geographic says has been one of Australia's most popular tourist stops since the beginning of the 20th century.

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal peoples have had a powerful connection to their land, and one — Anangu elder Tony Tjamiwa — explained that while visitors might photograph a rock, there was much more to Uluru: "He should get another lens — see straight inside. He would see that Kuniya living right inside there, as from the beginning. He might throw his camera away then."

Kuniya, says Parks Australia, was a giant python who once hatched her eggs at Uluru. It was the same place where her nephew was killed by a group of poisonous snakes, and where Kuniya first took her revenge on the murderous snakes and then merged with Uluru, where she remains.

It's easy to see how the actions of countless tourists have brought with them an infinite amount of pain, but there's good news: As of October 26, 2019, climbing on Australia's Uluru was no longer allowed.

The sacred footprints of a prophet

The Maqam Ibrahim is mentioned several times in the Quran, and for generations, Muslims who have gone to the Kaaba in Mecca have been able to see it in person.

It's safely tucked away behind metal and glass, and that's not entirely surprising. According to the Madain Project, the stone was actually broken sometime in the eighth century and pieced back together with the help of a silver and gold case.

Even then, it was already old, and there are a few different stories behind it. They agree, though, that the stone holds the footprints of the prophet Ibrahim. One version says that when Ibrahim was building the Kaaba, he stood on the stone, and his footprints were preserved. There's another belief, though, and that's the idea that Allah sent Ibrahim the Maqam Ibrahim — along with two other sacred stones — and that it marks the place where the prophet stood to offer prayers upon the completion of the Kaaba.

The Quran calls the Maqam Ibrahim a place of peace and prayer, and it continues to be at the heart of pilgrimages today.

Togo's sacred stones bring hope ... and warnings

Voodoo is one of the world's ancient religions, and at the center of the Epe Ekpe festival in Togo is a sacred stone. Every year, a voodoo priest heads into a sacred forest near the village of Glidji and emerges with the sacred stone. The color of the stone is thought to foreshadow the events of the coming year, and it can also send a very important message about what the gods think of the activities of mankind.

In 2004, NPR says the priest emerged holding a white stone — and it was a huge deal. White stones signified coming happiness, and seeing a white stone meant the faithful assembled at the village could kick off the new year with a sense of hopefulness.

It's not always such good news, though. A red stone is a clear sign that there's danger and tragedy on the horizon, and in 2015, Gulf News reported that the turquoise blue stone brought from the forest sent a very direct message. Guin elder Togbe Kombete interpreted: "We have offended our ancestors with our little squabbles. We must sit down quickly around a table and talk so we no longer have these small problems."

The ceremony of the sacred stone officially started in 1663, and some people travel a long way to be there. One attendee explained: "It's the tradition that our ancestors left us and I will never abandon it. This sacred stone is my spirit."

The most famous of all stone circles

When it comes to famous stones, the one with the most name recognition might be Stonehenge. Even those with only a passing familiarity with ancient history know that it's been linked to the religious beliefs of Britain's earliest Neolithic farmers, but there've been some fascinating developments in the study of the 5,000-year-old monument.

The medieval writer Geoffrey of Monmouth said that it was Merlin who assembled the stone circle in England after stealing it from Ireland, and according to The Guardian, it's entirely possible there's a bit of truth to the story.

Researchers have discovered a stone circle in what's now Wales, but an important footnote to that is that the land was considered Irish territory at the time Geoffrey was writing. Not only do Stonehenge's stones fit into the holes of the earlier monument, but researchers say that it's such a good match that it fits "like a key in a lock." It implies that the monument was assembled in Wales — about three miles from where the stones were quarried — and then disassembled and dragged 140 miles to where it now sits.

That's not the only fascinating discovery 2021 brought, either. Live Science says that's when researchers from the University of Brighton analyzed a core drilled from Stonehenge back in 1958 — and discovered that parts of the rock are 1.6 billion years old.

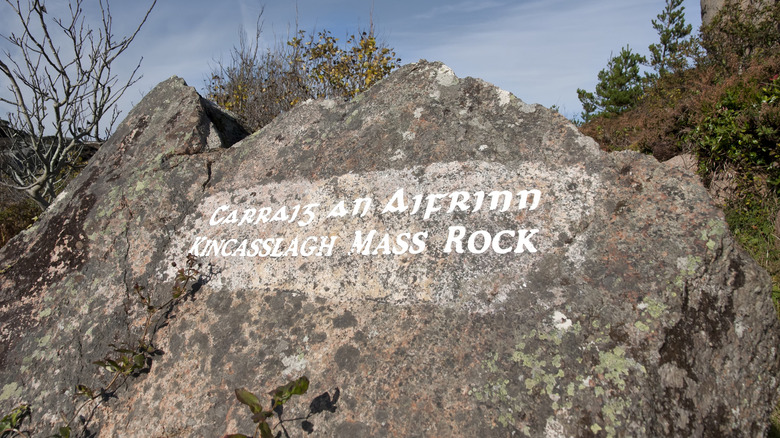

When saying Mass was punishable by death

It's no secret that starting with Henry VIII's determination to get both divorces and sons, there was a massive schism in Christianity. While England followed their king, Ireland held onto their Catholic ways — and between the 16th and 18th centuries, observing Mass was a crime punishable by death.

It got bad when Edward VI banned Mass, and it got worse when Oliver Cromwell showed up, says ACN Ireland. The answer was to continue to do what Catholics had been doing for a long time — take Mass out of the churches and hold them on altar-shaped rocks that were consecrated for secret ceremonies.

According to UK Research and Innovation's Arts and Humanities Research Council, the locations of Mass rocks weren't recorded — it was simply too dangerous, as priest-hunters absolutely knew about them. Each county had hundreds of Mass rocks, and many sites were chosen because they held an innate spirituality and were connected to pre-Christian, pagan worship. They were often well-hidden, difficult to get to, and generally not talked about.

Some are still in use today. The movement to take Mass back to these centuries-old places came with Friar Gerard Quirke's celebration of a special Easter Mass at a rock on Achill Island, and The Tablet says that led to a movement to recognize the June 20th Feast of the Irish Martyrs at Mass rocks across the country.

The sacred rock destroyed with dynamite

Mistaseni was a giant rock that stood on the plains of Saskatchewan. It was, says the National Post, at one time the meeting place used by different groups of Cree, and when they would meet in the spring, the crowd would spread out for miles in each direction. It was more than a meeting place, though.

The rock was called the Buffalo Child Stone and represented the spirit of a child who was long ago lost on the plains and then raised by the buffalo. He thought he was one of them until he saw his reflection, and when his buffalo family told him the truth, he returned to his human family. After having a hard time seeing buffalo meat and hides, he returned to his herd and was transformed into the buffalo he'd grown up as.

The rock stood until 1966, and here's where the tale takes a terrible turn. The 400-ton rock sat in an area that was going to be submerged by a lake with the construction of Gardiner Dam, and amid a push to save the stone, the government decided to dynamite it instead.

Fast-forward to 2015, and a diver named Steven Thair had researched the location of the stone and then tried to find it. He did: The remains of the stone are still there, lying in jagged pieces beneath the surface of Lake Diefenbaker.

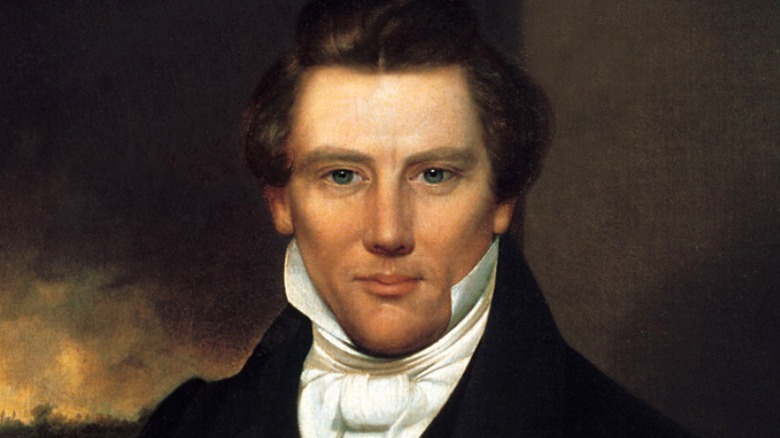

The stones that allowed for the translation of the Book of Mormon

Belief in the divinity of seer stones, explains The Joseph Smith Papers, goes back a long time. During the medieval era, stones were used to find lost items or other invisible things, and that belief was brought to the U.S. with European immigrants.

Joseph Smith regularly used seer stones — occasionally in the search for buried treasure — and when his angel appeared to him with instructions on translating the Book of Mormon, the use of two seer stones was in those instructions, too. It was a relatively unique use for seer stones, and according to Deseret News, the precise information of how, when, and what stones is kind of vague.

They do say, however, that Smith had several different stones, although where he got them from isn't clear. Two stones — which together made one seer stone — were said to have been given to him by the angel, while other stones he discovered along Lake Erie ... or while he was digging a well. His papers indicate that he used a white seer stone, a brown one, and the two Nephite stones, which are the ones that showed him the Book of Mormon, written one sentence (and one name) at a time.

It was only in 2015 that the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints released official photos of the seer stone (via KUTV), before it was moved to Harmony, Pennsylvania, and the LDS church visitors' center.

The heart of Islam

Mecca is at the center of the Islamic world, but more specifically, it's the Kaaba at the center Islamic pilgrimages. Set into one corner of the Kaaba is the Black Stone. According to traditional beliefs, it was Ibrahim who built the Kaaba and Muhammad who helped rebuild it — and, in doing so, set the Black Stone into place.

The Black Stone, says The Telegraph, is believed to have been heaven-sent after Adam's fall from grace. It was sent as a message to indicate the spot where a new altar was going to be built, and originally, it was white. It only turned black when it was touched by those who had sinned, and kissing it — honestly and with good intentions — is thought to connect a person to it: The stone will give witness to those people during the end times.

As with many religious artifacts, there are a few different stories around the Black Stone. Another tradition says that it was the angel Gabriel who gave the sacred stone to Ibrahim as he was building the Kaaba, with yet another saying that it goes back to Adam himself.

In 2021, the Saudi government released an image of the stone that was taken with almost unimaginable detail. The 49,000-megapixel image was a composite of 1,050 individual photos that were 160 GB each, and according to CNN, the photos support one of the leading theories behind the origin of the stone: It's believed to be a meteorite, and the scientific community agreed it did fall from above.

The most sacred place in England

When the British Pilgrimage Trust laid out their 110 different routes, they went through a number of ancient sites. Arguably one of the most important is Avebury, which The Guardian describes as one of the most revered places in the country — and it's been that way for somewhere around 5,000 years.

Avebury, says English Heritage, makes Stonehenge look a bit like amateur hour. Construction on the complex started around 2850 B.C., and while archaeologists don't have a complete handle on the whys, whats, and hows, they do have some pretty detailed guesses as to what's gone on there over the years.

While the exact rituals and ceremonies held there have been long lost to the mists of history, the general consensus is that the 100 stones of Avebury were erected as a sacred link between the earthly and the divine. Just what that divine power was undoubtedly has changed over the course of thousands of years, and Guidelines to Britain says that archaeological finds show that it was a place to gather and feast. Some believe it was built as an offering to the deities that controlled the weather, in hopes that this earthly acknowledgement would help keep the builders safe from things like drought, disease, and, in turn, starvation.

The sacred mountain where all are welcome

Most religious artifacts are claimed by just one or two religions, but Adam's Peak is a sacred mountain in Sri Lanka that is important to all believers and nonbelievers alike.

According to the Fair Earth Foundation, around 20,000 people a year climb Adam's Peak, and each person has their own reasons. Some are religious: At the top of the peak is a footprint, with different religions applying different significance. Those who follow Islam and Christianity belief it marks the first step Adam took after his banishment from the Garden of Eden, while Buddhists believe it's the footprint of Buddha, and Hindus believe it marks a footstep of Lord Shiva.

Dawn says it's also a place of pilgrimage for atheists, too, for different reasons. Some want to climb the mountain and see the sun rise over some of the most stunning views in the world, while others search for mental clarity. And people have been visiting for a long time: Sri Lanka Travel says the peak and footprint were a pilgrimage destination starting sometime around 1100, and even Marco Polo made the ascent alongside monks and kings.

The ancient rock once worshipped as a divine fish

The area of Colombia that's home to El Peñon de Guatape is pretty flat, says Atlas Obscura, and the rock — all 10 million tons and 650 feet of it — stands out over the landscape. By the middle of the 20th century, it was just another rock in the way ... until locals climbed it in an expedition that took a whopping five days. That was the beginning of the construction of a staircase within the rock's single crack, and the transformation from sacred spot to tourist attraction. Today, visitors can spend a few bucks to climb the 649 steps to some incredible views, but to the Tahamí people who used to live there, the rock meant so much more.

According to Outdoor Revival, the Tahamí who once lived in the area heavily relied on fishing for survival. Among their deities was a divine fish named Batolito, and regular offerings to Batolito helped guarantee bountiful fish.

Batolito, however, wasn't exactly a god — and when the gods realized how devout the Tahamí were, they decided to do a little teaching ... in a supreme deity sort of way. Batolito leapt from the waters to protect his people, and while he succeeded in driving off the gods, he fell to the ground, mortally wounded. He became El Peñon, and his faithful continued to worship him until they, too, retreated into the mists of long-lost history.

The centuries-old tale of Sugar Loaf

Sugar Loaf isn't exactly a mountain — according to the Mackinac Island Tourist Bureau, it's the tallest of a handful of rock formations on the island, called limestone stacks. It's about 75 feet tall, and it was formed around the same time the Great Lakes were. Geologists say it was the movement of an ancient glacier that carved the peak, but the area's Native American tribes have another story.

To them, Sugar Loaf is the place where Manabozho, the half-human, half-divine messenger of the Great Spirit, went to spend his final days. As he was dying, he was found and approached by 10 men, each of whom asked him for a gift. When one asked him for eternal life — a gift that not even Manabozho himself possessed — he turned on the man in anger. With one gesture from the demigod, the mortal man started to grow and grow ... until he became 75 feet tall and turned into the limestone structure that is now Sugar Loaf.

In another version of the story, Mackinac Island is known as the Great Turtle, and Sugar Loaf is revered as the home of the Great Spirit.

Cup, chalice, or stone?

Indiana Jones famously pointed out that the cup of a carpenter wouldn't contain 10 pounds of gold and as many jewels, but there's another version of the Holy Grail that's even stranger.

The Grail first shows up in Arthurian legend in the works of Chretien de Troyes, and there, University of Bristol Reader in Medieval Literature Leah Tether says (via The Conversation) it's described as a wide platter. One of the knights who fails in the quest for Chretien's grail is Parzival (or Perceval), and his story is picked up by Wolfram von Eschenbach in around 1210.

But here, the Grail isn't a cup or a dish at all — it's a stone. Oxford Scholarship Online says that Parzival's Grail was actually a consecrated altar made from a green gemstone and absolutely immoveable for any man. Only a woman could move the altar, and as the story unfolds, audiences learn it was ultimately responsible for reuniting Muslims and Christians in peace. When Parzival finally fulfills his destiny as King of the Grail, he and his wife both act as custodians to the stone delivered to mankind by God himself, and on each Good Friday, the Holy Ghost descends from Heaven to place a wafer on the Grail and bestow divine powers (via the BBC).

An odd interpretation, for sure, but who's to say it's wrong?