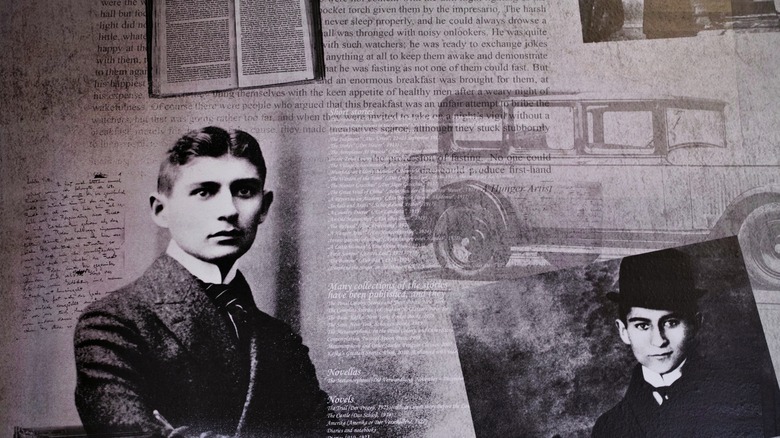

Franz Kafka's Tragic Real-Life Story

In common usage, the term "Kafkaesque" refers to something tthat is frustratingly convoluted and pointless. This is a common theme in writer Franz Kafka's work — his protagonists are often trying to navigate a complex and painfully confusing system outside of their control. Noah Tavlin for TED-Ed explains, "His tragicomic stories act as a form of mythology for the modern industrial age, employing dream logic to explore the relationships between systems of arbitrary power and the individuals caught up in them."

While Kafka's stories are often grim, they also embrace the humor in the absurd situations that the characters find themselves in, whether that be a god confined to his desk due to paperwork or a man unexpectedly transformed into an enormous bug.

From the unending bureaucratic nightmare of "The Trial" to the body horror of "Metamorphosis," Kafka's work invites the reader into intensely uncomfortable and unsettling worlds — not unlike his own. This is Franz Kafka's tragic real-life story.

Franz Kafka had an unhappy childhood

Despite living with both parents and three sisters, Franz Kafka had an isolated youth. The Kafka Museum reports that he "suffered from being left to himself as well as from insufficient parental affection and lack of emotional ties with his parents."

His relationship with his authoritarian father was a difficult one, with Kafka stating that he was afraid of his father, and that they were unable to communicate. In a letter to his father that was never sent, Kafka recalls his father once telling him, "If I have not treated you as fathers usually treat their children, it is just because I cannot pretend as others can."

The family moved often when Kafka was growing up, but remained in the city of Prague. According to the Kafka Museum, they primarily spoke German influenced by Yiddish when Kafka was growing up, while everyone around them spoke Czech. As a young child, Kafka's father sent him to a German elementary school with Czech classes so that he would be bilingual.

Kafka's early years influenced his views on both family and schooling. He expressed a view that both parents and schools are "bad educators," because they "suppress the child's individuality."

Franz Kafka had a confused relationship with Judaism

In his unsent letter to his father, Franz Kafka remarks on the guilt he felt as a child for not attending synagogue often enough, saying that he felt he was letting his father down. His description of his father's relationship with Judaism indicates that it was more about tradition than faith:

"A child hyper-actively observant out of sheer anxiety could not possibly be made to understand that the few insipid gestures you performed in the name of Judaism had some higher meaning. For you, they had their meaning as token reminders of an earlier time; that was why you wanted to pass them to me. But since even for your self they no longer held any intrinsic value of their own you could only do so by threats or persuasion."

Kafka would come to love the Yiddish theater in Prague, and Yiddish literature in general, which he described as having "an uninterrupted tradition of national struggle." According to Harriet L. Parmet's paper "The Jewish Essence of Franz Kafka," he was attracted to it because it was the opposite of the way he wrote his own work, which was "an agonizing exploration of a private world."

His interest led him to study Jewish history, Hebrew, and even Zionist philosophy when he was older. It did not lead to a tighter bond with his father however. Kafka described his father as "nauseated" by the Jewish writing he showed him.

Franz Kafka was a nonconformist

Franz Kafka's interests ranged far beyond Yiddish literature. He read the works of Charles Darwin and famous German scientist Ernst Haeckel. He was particularly fascinated by the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. According to Sander L. Gilman's biography "Franz Kafka," at 17 Kafka even read passages of Nietzsche aloud to a girl he was interested in. Kafka's wide reading of philosophy and ideas would eventually lead to him declaring himself an atheist, as well as questioning the political and economic system that he lived in.

Kafka's high school friend Hugo Bergmann described them both experiencing "the thrill of nonconformity." Bergmann was a Zionist, while Kafka was a socialist. These two belief systems were not at odds, and in fact when Kafka was young, "some young Jews ... saw socialism as an extension of their Jewish identity and were pleased simultaniously to be socialists and members of Zionist organizations," according to Gilman.

Evidence of these beliefs can be found in his work. Kafka's writing was praised in the Soviet press for its depiction of "the destructive power of money" and "the truth about the anti-human nature of capitalist relationships," as quoted in Emily Tall's article "Who's Afraid of Franz Kafka?: Kafka Criticism in the Soviet Union."

Franz Kafka experienced anti-semitism in Prague

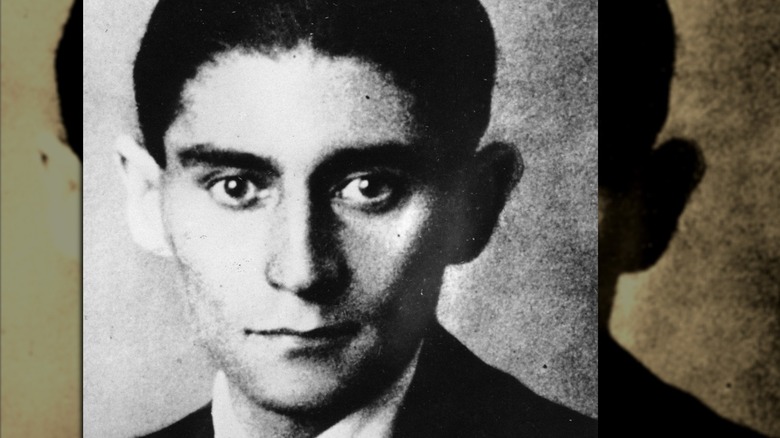

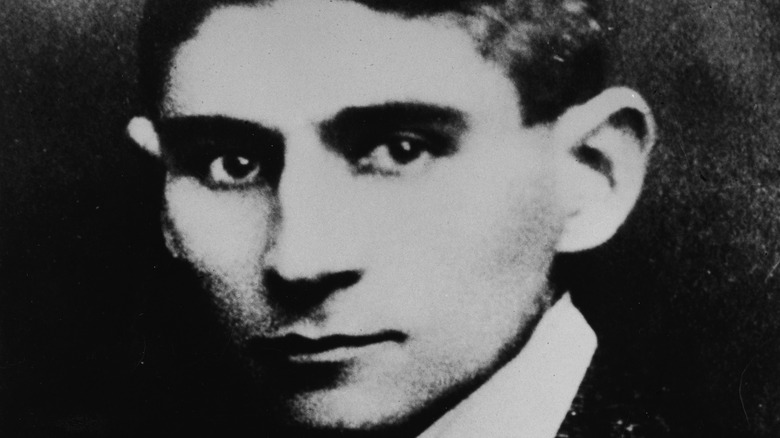

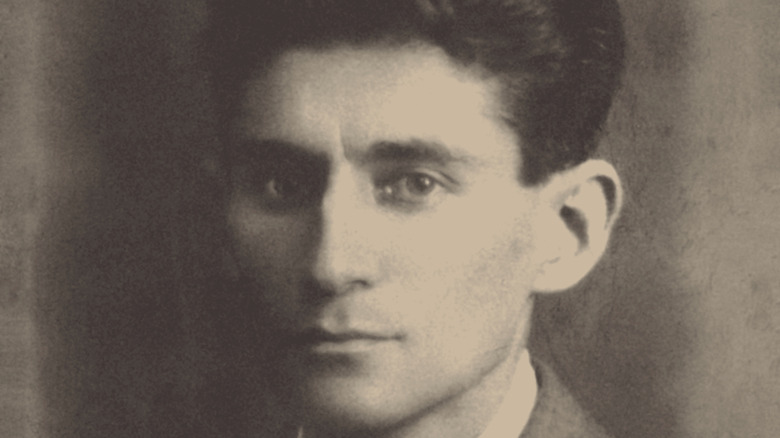

Though Franz Kafka would declare himself an atheist, Harriet L. Parmet's paper "The Jewish Essence of Franz Kafka" states, "who [Kafka] was cannot possibly be understood without realizing his being Jewish ... in turn of the century Prague was as vital a component of his identity as his dark hair and deeply brooding eyes."

In "Conversations with Kafka," the writer is quoted as describing that while the company that he worked for came out of the work of the labor movement, and one would expect it would be progressive, he was the only Jewish person to work there, saying "I function as the solitary display-Jew."

In the early 1920s, Kafka predicted that anti-semtism would continue to spread and, "seize ahold of the masses," and there was an ever-present threat of anti-semetic violence in the city of Prague while Kafka lived there. In "Kafka as a Jew” Walter H. Sokel states that, "The German and Czechs of Bohemia fought each other bitterly, but were united against a common enemy in the Jews."

During Kafka's teenage years and again when he was in his early 30s, there were mass anti-semetic riots in Prague. Jewish people living there had to be guarded by the military. Kafka chafed against this, describing, "the disgusting shame of perennially living under protection."

Isolation was a recurring theme in Franz Kafka's work

"Man is wretched," Franz Kafka is quoted as saying to his friend Gustav Janouch, "because amid the continually increasing masses he becomes minute by minute more isolated."

The struggle to fit into society is at the heart of many of Kafka's works, with isolation being one of the most frequently cited themes in his writing. It's an experience that he understood intimately. From his distant relationship with his father (Kafka himself once stated that he wrote because he couldn't speak to his father in real life) to growing up and working in a society that despised him for being Jewish, Kafka felt alienated from the people around him throughout his life.

Britannica goes so far as to describe the way Kafka lived every day as "a double life." Most people who met him found him charming and likable in person, but he truly despised the daily routine of his day job, and struggled with his personal relationships and the society around him.

Franz Kafka found his day job as a lawyer torturous

After high school Franz Kafka obtained a law degree and began working at the Workmen's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia, where he routinely dealt with the bureaucracy around industrial injuries.

As noted by Richard Posner's article "Kafka: The Writer as Lawyer," "he was a diligent and conscientious employee, highly valued by his superiors," and he has even sometimes been credited with the invention of the safety helmet during his employment. However, according to Biography, he despised his time there.

One reason for Kafka's hatred of his work was that he would have preferred to devote his time to writing, but it did not prevent him from writing all together. He worked at the insurance agency from 1908 to 1922. Despite Kafka's stated hatred of the job, the years that he was working there were also some of his most productive years as a writer. The bureaucracy he traversed and the horrific accidents he became aware of while employed there are believed to have inspired his work.

Franz Kafka's closest friend betrayed him

While Frankz Kafka was studying law degree at the University of Prague, he met Max Brod, who would go on to become his close friend.

Brod was also studying law, and like Kafka was also a writer. In almost every other way, they could not have been more different. The New York Times stated that Brod was "an extrovert, Zionist, womanizer, novelist, poet, critic, composer and constitutional optimist," and that "Brod had a tremendous capacity for survival."

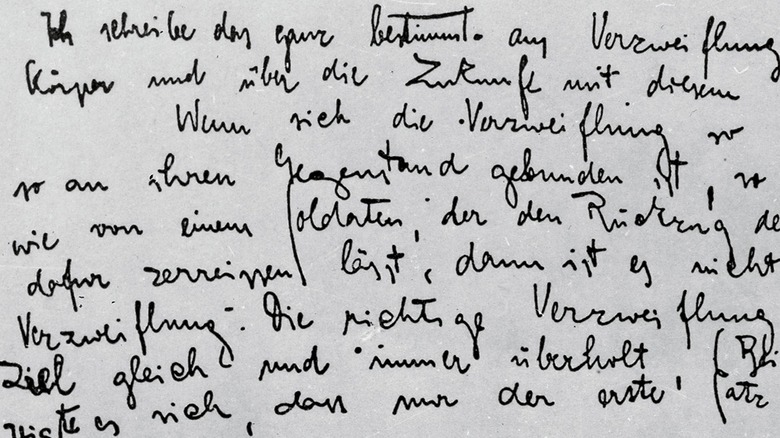

Their friendship was so strong that Kafka would ultimately make him his literary executor, leaving Brod in charge of his work — a task that put honoring his friend's wishes and preservation of his art at odds. Despite devoting his life to writing, Kafka is quoted in the Australian Financial Review as dismissing his own work as, "nothing more than my own materialisation of horror. It shouldn't be printed at all. It should be burnt." This is exactly what Kafka asked Max Brod to do. Kafka instructed his lifelong friend to destroy all the unpublished writing that Kafka would leave behind upon his death. But Brod didn't honor his friend's dying wishes.

Franz Kafka's early relationships didn't work out

Franz Kafka's romantic relationships were as fraught as his family ones. The first of his known relationships was with Selma Kohn, the girl that Kafka read Nietzche to. Kafka met Kohn while he was in high school, and as reported by the Kafka Museum, he wrote her a poem in her scrapbook, which remains the earliest piece of Kafka's writing that has been found. However, within two years he felt "indifferent" towards her. He also briefly dated a young woman named Hedwig Weiler, but the relationship ended quickly, "on account of Kafka's worries about the future."

In 1913, Kafka was staying at a sanatorium in northern Italy. There he met a young Christian woman named Gerti Wasner, and they had a brief relationship during the few weeks of Kafka's stay. According to Professor Sander Gilman, when Wasner left the sanatorium, he was "overwhelmed." But Kafka had already met one of the most significant women in his life: Max Brod's cousin.

Franz Kafka's failed relationship with Felice Bauer

In the summer of 1912, Franz Kafka visited Max Brod's home to bring him some of his manuscripts. There, he met Felice Bauer, Brod's cousin. He became enamored with her immediately. But this was to be just one of a few times that they actually met in person, since Kafka canceled many of their planned meetings at the last minute. However they exchanged hundreds of letters. The Guardian states, "the love he felt for Bauer was constructed entirely in writing, the content and frequency of which he could control." They were engaged twice, but never married.

They were engaged in 1914, and then again in 1917, but the marriage was called off, in part because of Kafka's poor health. Shortly after, a friend of Bauer's named Grete Bloch confronted Bauer with letters that Kafka had written her over the course of a year. While it was never verified, Brod reportedly believed that Kafka was the father of Bloch's child.

Franz Kafka suffered from tuberculosis and survived the Spanish Flu

In the summer of 1917, when Franz Kafka was only 34 years old, he experienced a pulmonary haemorrhage.This eventually led to tuberculosis.

Kafka struggled to work after his illness began, though the insurance company where he worked was loath to let him go, and even promoted him while he was on extended sick leave. His failing health was also given as one of the reasons for the end of his engagement to Felice Bauer.

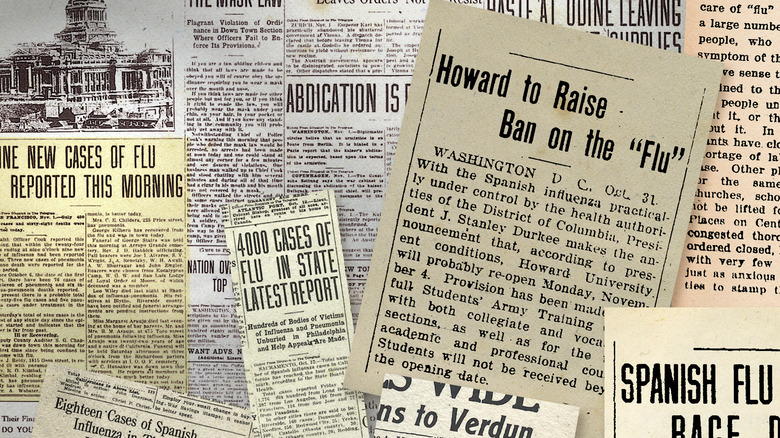

In 1918, he contracted the dreaded Spanish Flu, which the Centers for Disease Control refers to as "the most severe pandemic in recent history," infecting approximately one third of people on Earth and killing at least fifty million. Remarkably, Kafka survived.

According to the Kafka Museum, he also struggled with frequent headaches, sensitivity to noise, fatigue, and periods of insomnia. Kafka believed that the source of his illness was the result of a "battle between good and evil within himself."

Franz Kafka struggled with mental health issues

In 1912, Kafka wrote to Max Brod and told him that "he had come very close to suicide." According to Felisati and Sperati's paper "Franz Kafka (1883 – 1924)," he struggled with extreme anxiety and depression. His condition was described as "self-destructive mania, the need to torment and humiliate himself, the sense of personal emptiness and helplessness." In 1920, he asked his doctor to give him "a fatal dose of opium," but was refused.

Modern researchers, including M. M. Fichter, have posthumously diagnosed Kafka with "an atypical anorexia nervosa" based on his diaries and letters. Some have cited themes in his work as being inspired by his personal experience, in particular his short story "The Hunger Artist." It tells the story of a performer who entertains audiences by starving himself. The manager forbids starving himself for too long, to ensure his survival. Eventually, these performances become unpopular, and the protagonist is able to truly starve himself outside of the public eye. Before he dies, the hunger artist confesses that he simply couldn't find food he enjoyed. When he starves to death, he is replaced by a joyful panther that entertains the public and eats often.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

If you are struggling with an eating disorder, or know someone who is, help is available. Visit the National Eating Disorders Association website or contact NEDA's Live Helpline at 1-800-931-2237. You can also receive 24/7 Crisis Support via text (send NEDA to 741-741).

Franz Kafka never married, despite several engagements

In 1919, while staying in a boarding house to attempt to recover from a bout of illness, Franz Kafka met Julie Wohryzek, a young woman whose fiance had died in the war. He described her as "cheerful and carefree." As with Felice Bauer before, he asked Wohryzek to marry him, but their engagement did not last long. One reason may be that Kafka's father objected to their marriage. Although the date was set for the wedding, Kafka called it off via letter and suggested they stay together without being married.

But by this time he had already met Milena Jesenká, who the Kafka Museum refers to as "the second great love of Kafka's life." Jesenká was unhappily married, and she translated several of Kafka's works from German into Czech. The two only met in person twice.

Finally, in 1923, Kafka met a woman named Dora Diamant, who at 19 was 20 years Kafka's junior. Although they never married, they did move to Berlin together. The Kafka Museum describes their time in the city as extremely difficult because "they could not afford electricity ... they used candle ends to heat up [their] food."

Franz Kafka died young after a battle with tuberculosis

Franz Kafka's health deteriorated between Christmas 1923 and the start of 1924, and by the end of February 1924 he was in a critical condition, according to the Kafka Museum.

When Kafka told Max Brod about his illness, Brod responded with "You are happy in your unhappiness," according to Literary Hub. Kafka told him that in truth he had "a terrible fear of dying," because he "has not yet lived." Brod consulted doctors about Kafka's condition behind his friend's back. As Kafka's health got worse, he endured multiple stays in hospitals, clinics, and sanatoriums.

In 1924, just one year after he had committed himself solely to his writing and aged just 40, he died of tuberculosis. Dora Diamant stayed with Kafka until his death. According to the Kafka Museum, shortly before he died, Kafka asked Diamont's father if he could marry her. Ultimately, her father refused, on the advice of his rabbi. Diamant said in a private letter to Kafka's family that the writer died while mid-sentence.

Against his wishes, Franz Kafka's manuscripts were published

According to the New York Times, Franz Kafka burned about 90% of his own work while he was alive. Dora Diamant believed that "he wanted to burn everything he had written in order to free his soul from these 'ghosts.' I respected his wish, and when he lay ill, I burnt things of his before his eyes." She did not speak publicly about him after his death.

Most of Kafka's work was unread at the time of his death. He had never completed an entire novel, and his short stories had gone largely unnoticed. Kafka had nominated Max Brod to act as his literary executor, telling him that the work "is to be burned unread and to the last page." But Brod, who had been a champion of Kafka's work while he was alive, chose not to destroy the manuscripts after his death.

Instead, he edited the manuscripts and had them published. This started a legal battle that would last 50 years. In 1988, one of the manuscripts left to Brod would ultimately be sold for $1.98 million. The books that Kafka wanted destroyed and were published against his wishes made him "one of the major authors of the 20th century" after his death.