Here's What Happens To You When You Spend A Year In Space

Ask any group of children what they want to be when they grow up, and you're sure to hear "Astronaut!" from at least one or two voices. (Heck, ask any group of adults and you'll probably get the same result.) But, while being an astronaut is exciting, it's also dangerous — and not just because of the risk of a deadly explosion. Astronauts have to deal with living in space, and space has both radiation and weightlessness — two features that can cause lasting changes to the human body.

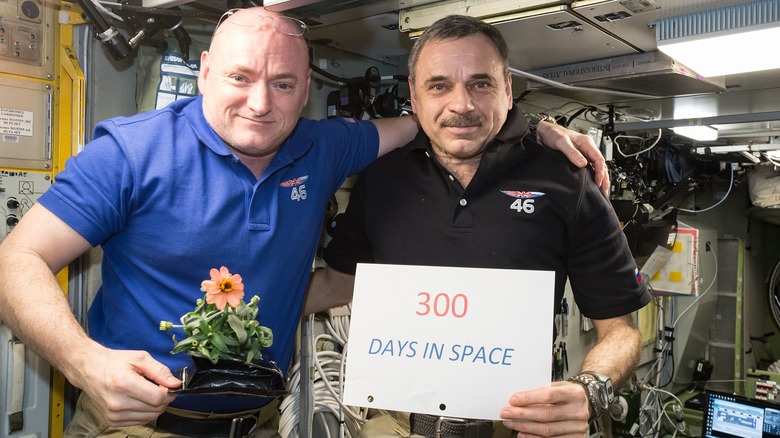

But, for decades, scientists have remained uncertain about the exact nature of these bodily changes. That all changed with an experiment that NASA conducted a few years ago. As NASA explains, this experiment involved two retired astronauts: twin brothers Scott and Mark Kelly. Starting in 2015, Scott Kelly was sent for a year-long mission to the International Space Station. Meanwhile, (now-Senator) Mark Kelly remained on Earth. By comparing vital signs, bodily fluids, and cognitive tests from both twins, NASA researchers sought to determine the exact changes that life in space has on the human body — down to the level of DNA.

There's a good chance you've already heard of NASA's Twins Study; it received a considerable amount of media attention a few years ago. But have you heard about the study's results? Probably not; they were published in the journal Science in 2019 with little notice from the press. So, allow us to tell you what happens to a human who spends a year in space.

Spending a year in space can hurt your bones, muscles, and even your cognition

Two of the directors of NASA's Twin Study — Dr. Susan Bailey and Dr. Christopher Mason — went on the radio show "Science Friday" to discuss the results of their experiment. Drs. Bailey and Mason revealed a number of surprising findings about the changes to astronaut Scott Kelly's body over his year-long stay in space.

For one thing, Kelly suffered noticeable bone loss; "In his urine, you could see the calcium sort of disappearing," Dr. Mason revealed. Likewise, a year in microgravity led to muscle loss. Both bone and muscle loss have long been understood to result from microgravity; as a result, NASA has installed special exercise equipment — like treadmills — on the International Space Station (per NASA). However, when astronaut Kelly was tested while in space, NASA's researchers found that the genes responsible for building bone and muscle mass were in an active state. Kelly's body was actively fighting (without much success) to restore what it had lost; the researchers called it a "Sisyphean struggle."

But the Twins Study found something even more surprising: returning from a year in space can negatively affect cognition. Per Dr. Mason, once Kelly landed back on Earth, cognitive tests revealed that his mind had declined in both speed and accuracy; he scored worse on cognitive tests than he had while still in space. These cognitive impediments persisted for the full six months that astronaut Kelly was tested after landing — suggesting that they could even be permanent.

Living in space can change your DNA, and might lead to faster aging

Could returning from space lead to a duller mind? If so, that's certainly not good news for a future Mars colony. But, as Dr. Susan Bailey's told "Science Friday," astronaut Kelly's cognitive decline is more likely related to radiation exposure than the effects of microgravity — and she's hopeful that technological advancements will better protect future astronauts from radiation.

But, for now, radiation remains a major threat. Per Dr. Bailey, radiation exposure modified Scott Kelly's DNA over his one year in space; radiation led to rearrangements between his chromosomes, as well as within his chromosomes. Then, six months into his mission, Kelly's T cells — immune cells responsible for DNA repair — noticeably ramped up their action. Upon returning to Earth, many of Kelly's modified cells died out, but some genetic changes persisted. Thankfully, the researchers did not mention any lasting impacts to Kelly's health.

Additionally, the ends of a person's chromosomes — the "telomeres" — usually shrink in response to stress, which leads to faster aging. So, NASA was surprised to find that astronaut Kelly's telomeres actually lengthened while in space; it was only after he landed that they began to shrink rapidly until ultimately stabilizing. This was something the researchers were unable to explain, but it seems to imply that a return from space — not space itself — may lead to premature aging.

Of course, there's not much you can conclude from just one test subject. Naturally, NASA's researchers hope to study the health of many more astronauts in the years ahead.