What It Was Really Like To Party In Ancient Greece

For as much as we advance as a civilization and shed the archaic ways of the past, some things do not change even over thousands of years. Then and now, people love booze, and even though the ancient Greeks made and drank the stuff in far different ways, they usually got drunk at the local bar or at home with friends just like we do today.

That said, there's one striking difference between how we perceive alcohol in modern times and the ancient Greek world — in Greek history, drinking was inherently tied to religion. The ability to get drunk was viewed as a true gift from the gods, so the ancient Greeks never forgot to thank them for providing such pleasure. Yet even with the formalities involved at drinking parties and festivals, people certainly knew how to cut loose and have fun. And more often than not, enjoyment was the end result for everyone once the wine jars had been cracked open, from the poor laborers to the wealthiest nobles. Here's what it was really like to party in ancient Greece.

Common people drank at taverns

Hosting a party at home was much less of an option for most ancient Greeks, who did not have enough space in their houses or enough money to pay for such an affair. Thankfully, taverns were on nearly every corner, and here patrons of all walks of life could go to drink, especially in democratic cities like Athens.

Unlike the private drinking parties hosted by the wealthy, most taverns were open to almost anyone, including women and slaves. And since the local joints were also under much less pressure to look respectable, it was not uncommon for some places to get pretty wild at times, with a promiscuous atmosphere, according to Warwick Knowledge Center. It sounds just like the bars and clubs of today, where all sorts of people hook up.

The ancient Greeks were wine drinkers through and through, and taverns had plenty of it to go around. Tavern owners sold wine in bulk for the wealthy to drink at home, but they also opened the large wine jars to sell drinks by the cup too.

The rich threw house parties for dinner and drinks

Taverns were not just for the lower classes, and quite a few catered to wealthier clientele by serving the best vintages of wine. However, nobles partied at each other's houses when they wanted to avoid the lowly rabble. In aristocratic homes, honored guests were invited over knowing that an extravagant dinner came first, followed by drinking afterwards.

The staples food that all ancient Greeks enjoyed, like olives, cheeses, bread, figs, and grapes, would likely be served alongside various vegetables, and more exotic fare. Seafood was the most prized delicacy in an ancient Greek home, though there were others prized foods, such as some game birds, hares, sausages, offal, and various kinds of cake, according to James Davidson in "Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens." To the ancient Greeks, the best fish were eel, tuna, sea-perch or grouper, grey mullet, red mullet, gilthead, and seabass.

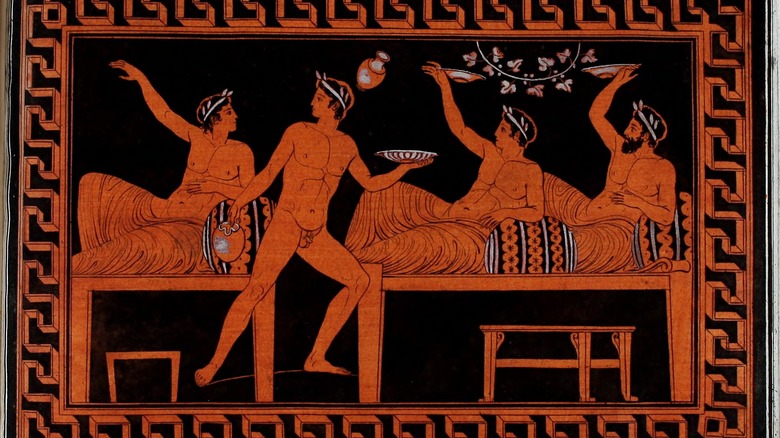

While the guests enjoyed their food, they reclined on couches, propping themselves up on their left elbow and using their right hand to eat. Once the food was gone and dinner was over, the most important part of the party began. The Greeks called this later phase a symposium, which meant "drinking together."

Aristocratic homes had party rooms

Many wealthy ancient Greek households had a special room for parties called an andrôn, or literally a "men's quarter." The large man cave was usually found near the front entrance of a noble's home to separate it from the private areas of the house. Anywhere from seven to 15 couches were arranged against the walls of this male dining room for several guests to recline on, according to the Iris. For larger parties where there were not enough couches, so it was common for guests to share, with two men reclining together.

Small, three-legged tables stood in front of the couches to hold snacks and for guests to occasionally set down their cups. Aside from that, the middle of the room was mostly empty, which created an intimate circle. Everyone in the room could clearly see each other and make eye contact. As the wine flowed, cups were filled counterclockwise, and symposia would also include story telling stories, and singing verses of songs.

Hosts showed off their wealth

The guests at these parties were almost always fellow nobles, so hosts wanted to impress. Alongside the fancy food, they would offer the finest vintages of wine, which was sometimes even chilled with snow to really show off.

The most luxurious homes were decorated with gilded ceilings, inlaid floors, and painted vases, according to Jessika Akmenkalns and Debby Sneed in "The Symposium in Ancient Greek Society." Wealthier nobles could afford more elaborate entertainment as well, with musicians, acrobats, or others hired to perform for the night.

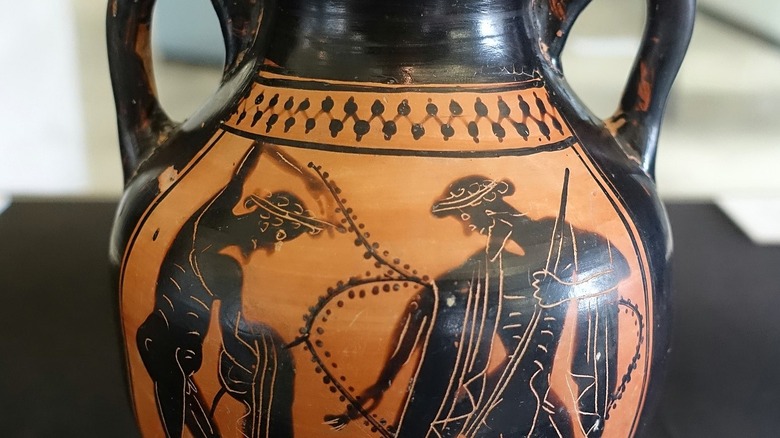

The guests not only reclined on expensive furniture, but also drank from the finest cups, sometimes made of bronze, silver, or gold. Other cups and drinking vessels, such as wine jugs, wine coolers, and wine-mixing ceramics called kraters, were beautifully decorated with episodes from myths, or everyday life, including scenes that occurred during actual drinking parties. Sometimes the painted ceramics depicted images of the inside jokes of the partiers.

Women were not allowed at symposia ... well, sort of

The symposia were reserved strictly for men, which really meant that "respectable" women were not allowed. That is the noblemen's wives, sisters, and daughters. One major exception to this rule was when all the guests to the party were family members. In this situation, it was totally fine for the women to join in the fun.

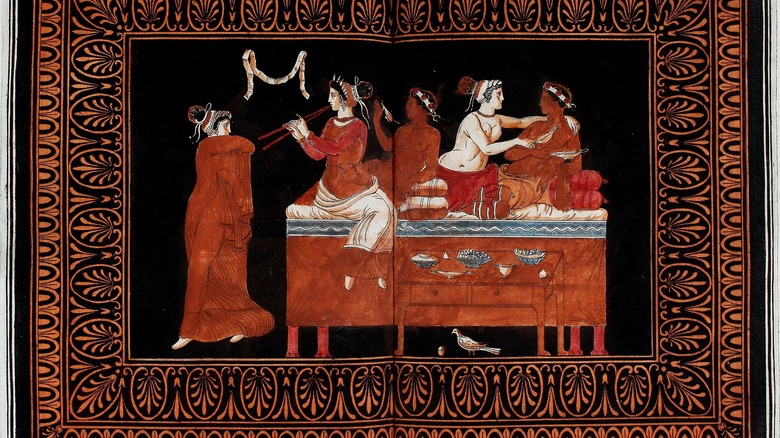

However, that doesn't mean that symposia were entirely male. Courtesans known as hetairai were a common feature of many of drinking parties. These women were not merely prostitutes, but instead were both highly educated and musically talented as well. Unlike the pornai, the lower-class sex workers who were found at the local tavern, courtesans were hired to flirt, converse, and play the flute as much as anything else. Encyclopaedia Romana says that it is likely that the courtesans were more educated than the wives and daughters the partygoers left at home, so the men probably found the drunken discussions quite fascinating and entertaining.

Aristocratic women had their own drinking parties

Wealthy women may have rarely attended symposia, but they had their own opportunities to drink with friends at luncheons, wedding feasts, private parties, and religious festivals. There were also festivals specifically for women like the Adonia, which was celebrated with private parties, according to Joan Burton in "Women's Commensality in the Ancient Greek World."

In specific parts of the Greek world, women also had more freedom to party. In philosophical communities, especially among the Pythagoreans in southern Italy and the Epicureans, women would take part in discussions over wine far more often. This was especially true in ancient Sparta, when the soldierly men were eating together in mess halls, and women threw parties at home, inviting the gals over for good food, drinks, and conversations. It is also quite possible that the poet Sappho and other important women in Lesbos held their own private parties in the sixth century B.C. as well.

A drinking ceremony took place after dinner

At symposia, once everyone had finished eating, slaves passed around water and washed the partygoers' hands. They then swept clean the floors from all the bones and shells that had dropped during the meal, and sometimes filled the room with perfume, or gave the guests garlands to wear, according to the Warwick Knowledge Center.

The drinking party then began with prayers and a specific number of toasts to the gods, which often included Dionysus, the god of wine. Every man drank the same amount for each toast and the wine was unmixed for the last time of the night. The Greeks believed that drinking straight wine all night could cause a man to go mad, and that only barbarians were foolish enough to drink wine without adding water first.

The partygoers then diluted the wine by mixing it with water in a giant bowl (the krater), and would fill several other kraters for the night too. According to "Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens," a half-wine, half-water mixture was sometimes drunk, but the most common measure was "two-sevenths, that is five parts water to two parts wine." Nobody served themselves wine, and instead a wine-pourer went around the circle and evenly distributed it to each guest, still making sure that everyone had the same amount to drink.

There was drunken conversation and musical entertainment

After the ceremonial start, the party became more like those of today. The guys told stories, sang songs and played instruments, discussed politics, recited poetry, or simply just talked about whatever was on their minds, according to World History Encyclopedia.

One popular game that was often played was the capping game. To start, the first man quoted a line of poetry, followed by the guy beside him, who had to quote the next line, and the game continued this way as it went around the circle. The rules of another version had the person up next quote a line that started with the last letter of the previous line of poetry. In the days long before cell phones or even before everything was written down, this was one of the ways the ancient Greeks memorized their great myths and pop culture.

As today, all parties were different, with the wilder ones involving lots more wine and much less poetry and philosophical discussion. There was usually plenty of sex going on at these parties too, either with the beautiful courtesans, or with each other, since homosexual love was not discriminated against as in later years. When these relationships occurred, they were commonly between a younger and an older man.

The dignified symposia of Plato and Xenophon

The symposia written about by the ancient authors Plato and Xenophon highlight the more respected parts of the drinking parties, showing that some were gatherings of intellectuals who discussed philosophy over food and wine. Getting trashed was not the goal at either party. In Plato's symposium they basically decided to "not make the night a 'tipsy affair,'" according to the University of Colorado, Boulder's Department of Classics.

The same source reports that at Xenophon's symposium, Socrates said, "If we pour ourselves immense draughts, it will be no long time before both our bodies and our minds reel, and we shall not be able even to draw breath, much less to speak sensibly." The courtesans did stay for this party, while the flute-girl was sent away during Plato's symposium.

Yet even the refined party described by Plato eventually broke down and loosened up quite a bit. Later in the night, a group came and crashed the party, getting everyone to drink way more, according to the Great Courses Daily. By dawn, the partiers were trashed, aside from Socrates and Aristophanes, who continued to argue and talk into the morning.

Many played the drinking game kottabos

Kottabos was played so often in aristocratic households that it was probably one of the reasons why the floor of the man cave was waterproof. The goal of the game was for guests to swirl around their cups and then fling the dregs of the wine at targets in the middle of the room. After several kraters were downed and everyone was drunk, there were probably a lot of misses that would have instead hit the guys across the room.

There were variations to the game too, such as balancing a plate on top of pole and trying to knock it off, or even attempting to spell the first initial of their lover's name on the floor. Another version had small saucers that floated on water in a basin, which the players then tried to sink with the dregs. Since it made less noise, this version of the game was considered to be the most civilized way to play, according to Atlas Obscura.

While continuing to recline on their left elbows, players placed two fingers of their right hand through their cup handle's loop and flung the dregs in a high arc to hit the targets. The Greeks thought the action was like throwing a javelin since their fingers went through the leather strap on the light spear in a similar way. The courtesans joined in the fun as well, and a sought-after prize for hitting a target was a kiss from these beautiful women.

Sometimes the bros got wasted and even threw around the furniture

When the guys got drunk, it was best case scenario that they simply went out into the streets singing and dancing, maybe waking up the neighbors. Some of these humorous events were immortalized in scenes on drinking vessels, such as one that depicts a man puking into a basin while a slave held his head and another that showed a more hysterical night when a group of men dressed up in women's clothes and paraded down the streets.

The Greeks were well aware of the increasing level of drunkenness that came after the party finished three or more kraters full of wine and everyone gradually lost control, according to James Davidson. Finishing four led to arrogance and overconfidence, after five came shouting, six down brought on obnoxious singing and dancing, seven led to fist fights, eight most likely had the neighbors making serious complaints, nine caused the partiers to puke up bile, and after ten came madness and hurling the furniture.

That's right, just like the insane frat parties of today, some of the most trashed bros tossed the furniture around, especially if they managed to finish off ten kraters throughout the night. One bizarre ancient Greek story told of a symposium where a group of young men got so wasted during a storm that they thought they were on a ship at sea, so they threw the furniture out of the house in order to "lighten the ship" so they would not drown.

There were religious festivals and feasts for everyone

In Athens, festivals were quite common, with 120 of them held throughout the year. Although there were formal aspects to these festivals, like processions and sacrifices, they were ultimately times for people to come together and relax as they celebrated with feasts, musical performances, and athletic contests, often with much drinking as well, of course.

The Athenians also introduced dramas and comedic plays to the festivals, which increased the amount of entertainment at the grand occasions, according to the Oxford Research Encyclopedias. The best religious holiday for the comedy writers was the Day of Misrule, when everyone was open to satire and ridicule — even the gods — to the great enjoyment of the audience. City dwellers loved festivals and showed up in large crowds, so the state poured a lot of funds into the events, making them more elaborate and improving the image of the city.

The Dionysia was the most lit festival

Everyone loved the festivals devoted to the god of wine, Dionysus, for obvious reasons. Yet women, slaves, and even prisoners, especially enjoyed the main festival, the Dionysia, since they had more freedom during the celebration than at any other time in their lives, which made the god very popular in Athens especially, according to the Collector. Not only were prisoners and slaves released from captivity, but women also had prominent roles in many of the rituals and ceremonies.

Among this liberating atmosphere, all sorts of bawdy activities happened. Large phallic statues were set up and displayed or paraded in a procession, along with contests to see who could down their jug of wine the fastest. And since the festival "days" began at sunset, the drinking could continue all night long. After five days of drunkenness, the partiers were allowed to rest for a day before the seventh and final day of the festival.

Partying in the Hellenistic Age

After the conquests of Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C., Greek culture like the symposia spread to all the Hellenistic kingdoms of the ancient world. In these newer versions of the parties, people drank while they ate much more often, removing the separation that used to happen between the two activities.

Plus, particularly powerful women and queens became more involved in drinking parties than ever before, according to "Women's Commensality in the Ancient Greek World." In a way to legitimize and display their power, queens held extravagant feasts just like their male counterparts. But even aristocratic women who were not royalty began to show up more and more to parties, especially after the third century B.C.

It wasn't just women who gained more opportunities to attend the elite, private parties — so too did men of the lower classes. According to the same source, at one particular Hellenistic symposium, the guests included both a soldier and even a horse-trainer, which showed that times had truly changed.