The Messed Up Truth About The Southern Redemption Movement

If you were to hear someone start talking about the Civil War and the things that came from or after it, what would come to mind? The Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln's assassination? Maybe the abolition of slavery and the policies of Reconstruction? What about Jim Crow?

Okay, the last one seems to jump ahead in history a little, but there is a connection there, and that connection has to do with a lesser known movement that was going on in the years after the Civil War, kind of alongside and following the Reconstruction era. Well, "lesser-known" might be a weird way to put it. It might be easier to say that the name "Southern Redemption" isn't heard all that often, but the ideas and actions that fall under its umbrella? Those are definitely pretty well known, tying into a bunch of racial violence, segregation, and overall pride in the Confederacy — all fairly storied things, to put it really lightly.

So get ready; this isn't exactly the brightest spot in American history.

What was Reconstruction?

Let's just start here. Yes, Reconstruction is definitely a different thing, but the seeds of the Southern Redemption movement were kind of sowed here.

According to History, Reconstruction is that era that directly followed the end of the Civil War, generally taking place between 1865 and 1877. Initially, it was just meant as the period of time that would welcome the South back into the Union and just generally put a stop to the actual fighting, but Northern politicians felt the South was being treated too leniently. Southern states could be readmitted to the Union through very vague oaths of loyalty, but that didn't ensure that anything would actually change. There was an expectation that the entire society of the South would be completely overhauled instead (via History). And that's where Reconstruction actually became about, well, reconstructing Southern society and changing it for the better. Doing away with slavery and creating institutions that would actually help newly-freed African Americans, then actually trying to enforce those rules in the South, where ex-Confederates were trying to circumvent those changes at all costs. Reconstruction was meant to be a time of change and progress, which it ultimately was. In more ways than one.

Where did Reconstruction go right?

For all that happened during Reconstruction — and all the questions as to whether or not it was even a success, or just an absolute failure — there were a number of things that did go pretty well. First, and probably most obvious, are the Reconstruction era Constitutional Amendments: the 13th, 14th, and 15 Amendments. The abolition of slavery country-wide, citizenship for African Americans, as well as the right to vote, respectively, are all really positive steps forward (via United States Senate). In a similar vein, there was also the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which, per the Federal Judicial Center, made it clear that newly freed slaves were allowed rights and protection under U.S. law.

But there was more than just legislation that happened during this time. The Republican party also funded various public works projects, improving infrastructure like railroads or state prisons and building up things like new public schools (via Anchor). (Granted, the results of that were more complicated in the long term, but we'll get there).

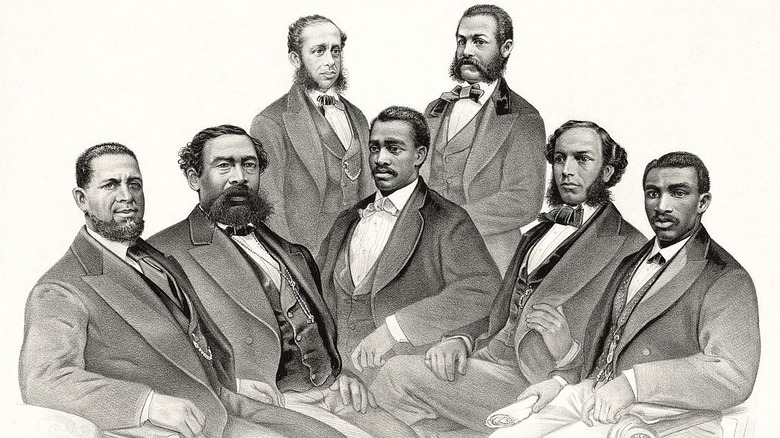

Going more deeply into the political ramifications, African Americans finally having the right to vote ended up massively affecting the political scene at large. According to the New York Times, the black vote brought a kind of Republican dominance into legislative assemblies — it also helped Grant win the Presidential election in 1868. Plus, it brought more African Americans themselves into political offices as Senators, Lieutenant Governors, and the like.

White Southerners felt threatened by Reconstruction

Of course, Reconstruction was a pretty massive restructuring of the way things had always been, especially in the South, where people really pushed back against all the ideals of Reconstruction. As the National Endowment For The Humanities puts it, in the South, none of this looked like progress; instead, it just looked like anarchy.

All of this power had by African American voters was kind of intimidating, because it had proved powerful already, given the number of Republicans entering office on the federal level (via New York Times). And that's all pretty well supported by the numbers. Because of, well, slavery, up to 90% of the African American population in the U.S. lived in the South, so it's sort of no surprise, that the changes brought by Reconstruction were so strongly felt there.

Basically, African American political power and freedom was a threat to those good old values of white supremacy, and white Southerners weren't ready to give that up. They wanted a return to their old way of life and would do so by any means necessary; that's where Redemption would come in.

The end of Reconstruction

For all the good that Reconstruction seemed to do (the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to name a few), and all the good intentions it started with, at the end of the day, it's been considered something of a failed experiment.

After a while, Northern interest in Reconstruction just waned (via History). It'd been a few years with decent progress, and it seemed like Northern politicians felt they'd done enough. They'd done their job, and could leave newly-freed Blacks to deal with everything on their own, per the New York Times (all despite a really militant White population which would restore White Supremacy at any cost). Basically, people just stopped caring, and the South was left to its own devices.

But to top it all off, the latter years of Reconstruction were colored by controversy and whispers of corruption. The actual projects that were funded during the Reconstruction era, backed in large part by the Republicans in power, obviously took money. Where did that money come from? Well, the answer to that was taxes. Quite a few of them, considering that, according to Anchor, the total price of all of those public works projects came out somewhere around $18 million. It was a lot of government spending coming from heavy taxes, and Conservatives at the time didn't agree with it, painting the situation as corruption, plain and simple. It wasn't even entirely untrue, though, with some of the borrowing and lending happening actually being ruled unconstitutional.

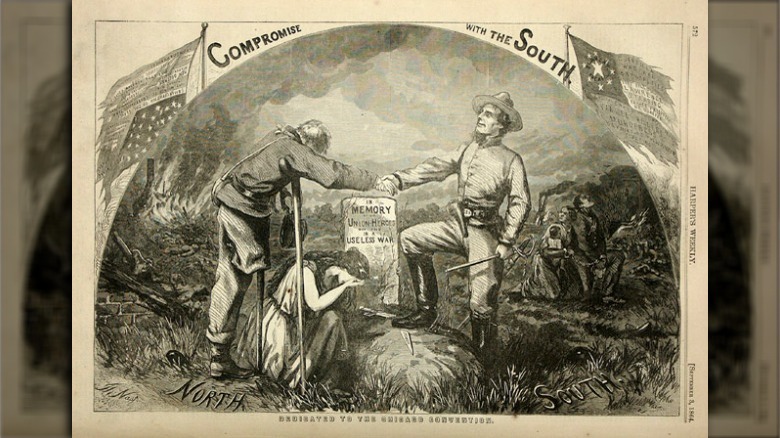

The Compromise of 1877

Reconstruction as a whole did have this sort of slow fizzle out, but there is a particular event that usually gets cited as the official end of the era. It's also a pretty good example of the whole problem of corruption that started surrounding Reconstruction era projects and politics.

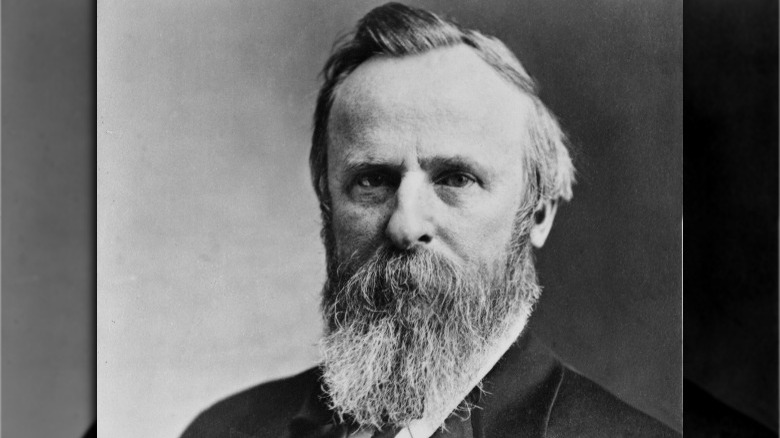

The Compromise of 1877 — or the Hayes-Tilden Compromise — is that event. Basically, according to History, it all started with the Presidential election of 1876, which pitted Republican Rutherford B. Hayes (pictured above) against Democrat Samuel B. Tilden. On Election Day, the Democrats seemed to come out on top, but the Republicans accused them of intimidating African American voters in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina (which was warranted, if not quite that simple). Congress tried to step in and leave the decision to a small commission, which had equal representation for both parties.

But under the noses of that commission, there was a separate, secret meeting, which came up with the actual compromise: Hayes would be given all of the electoral votes from disputed states, and in return, he would pull all federal troops out of the South. Hayes himself had actually promised to allow more self-government in the South; removing federal authority from the area did just that, basically giving the South free reign to ignore all the progress of Reconstruction and restore their old ways.

The Southern idea of Redemption

Yeah, there was more than one big "R" word movement going on at the same time, but while both Reconstruction and Redemption sound like pretty good things, purely by the connotation of the words themselves, they're two completely different things.

At its core, Redemption was basically the Southern response to all the changes going on due to Reconstruction, with the actual movement starting around 1873, according to the National Endowment for the Humanities. And at its simplest, it was a fight "stemmed from an adamant determination to restore white supremacy," as historian Rayford W. Logan puts it (via New York Times), as well as an attempt to regain political dominance by white Southern Democrats, just like it had been in the antebellum South. After all, to white Southerners at the time, African Americans were literally just a lesser, far inferior, group of people (via Encyclopedia.com). Putting them in positions of power posed a dangerous threat (which, to be fair, wasn't entirely wrong — they definitely were a threat to white supremacists and ex-Confederates still married to the old ways). Thus, putting superior white Southerners back in power was seen as a literal "redemption," restoring the balance of power that they believed to be right and proper.

Violence in the South

Is it any surprise that one of the hallmarks of Redemption is violence? Historian Rayford W. Logan that Southerners were willing to resort "to fraud, intimidation and murder in order to re-establish their own control" (via New York Times), and, well, yeah.

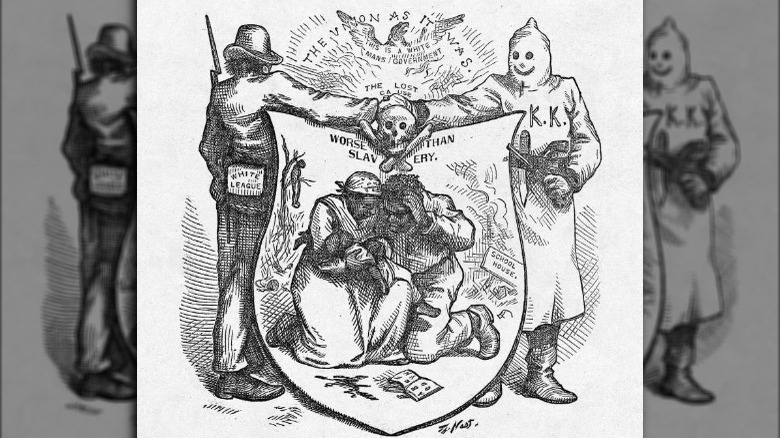

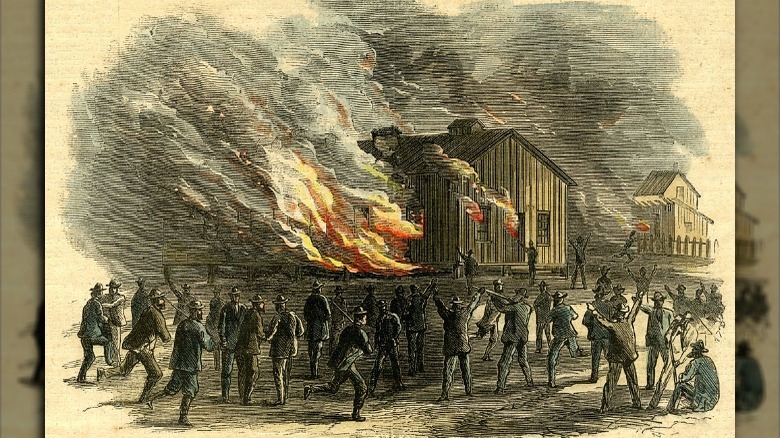

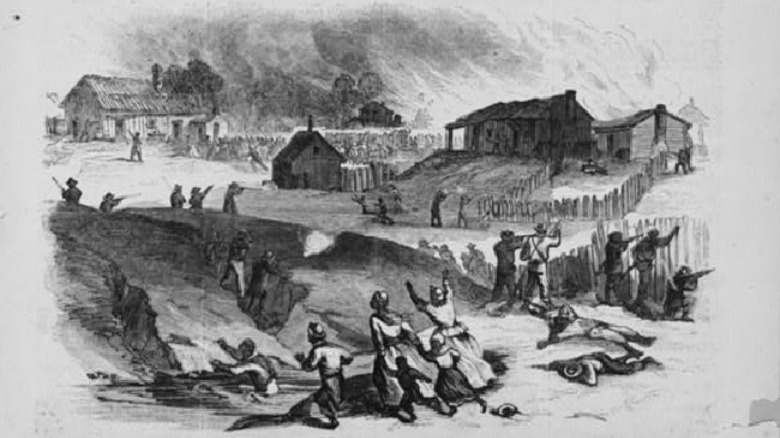

After all, this is the time period that birthed not just the Ku Klux Klan, but a bunch of other white supremacist, paramilitary groups (the White League and the Knights of the White Camelia, to name a couple) that were really similar, promoting terror before and around Redemption. Per Digital History, white Democrats resented both African Americans and Republicans for slighting them and their honor, filling their ranks with ex-Confederate soldiers and the wealthy. They would beat and murder African Americans, or would use force to take over government offices, leaving the bodies of their enemies in their wake. And none of this was subtle, with the federal government definitely taking notice; after all, there's a reason why certain states in the 1876 Presidential election were so contested, with gunfire ringing out during political meetings in South Carolina, leaving behind bloodshed that was likely a part of terror and intimidation tactics (via History).

Plus, all this violence was praised. The "Young People's History of North Carolina" described the KKK like vigilantes, framing them as nigh-mythical heroes who scared evildoers (African Americans and white Republicans) into submission. (If you read it and ignore the blatant bias, though, the description of the group is kind of horror-esque.)

Voter suppression tactics

Here's another one of those big facets of Redemption: voter suppression. Because while the Reconstruction era Constitutional Amendments did technically protect African Americans' right to vote, they didn't necessarily offer any protection from the South doing everything they could to find loopholes which would, effectively, take away that right (via the United States Senate).

Let's start out simple. Intimidation tactics. Shows of violence, massacres, and general bloodshed are mentioned as pretty common during the Reconstruction and Redemption eras; the New York Times brings up an incident in 1876, where African American voters were intimidated into not voting, allowing the Democrats to take back political power and do away with attempts at integration. Other times, as Digital History says, sometimes Democratic politicians just lied, claiming that they would defend African Americans' rights just to get their vote.

But then there were also the voting restrictions that Southern states started to push. Voting eligibility would only be granted by being able to afford certain poll taxes, pass literacy tests, or meet particular residency requirements. Supposedly, that was meant to keep the poor, ignorant, or violent away from the voting booths, except that wasn't true. After all, it wasn't put in place to keep poor white men away from voting; eventually, there was an admission that, no, this was entirely just about keeping African Americans away from the polls and subverting the 15th Amendment in a way that was, technically, still constitutional.

In the end, Redemption did work

Here's the really sad part of the story. For all the terrible things that came about because of Redemption, at the end of it all, it did actually do just what it was meant to. With Reconstruction falling apart, white supremacy did rise again, and in a pretty major way.

The North just didn't really care much for continuing to pursue Reconstruction era ideals. The federal government stopped trying to protect African American voters from Southern violence (via History). African Americans were completely on their own, and at a serious disadvantage, more efforts going to further suppressing and silencing African American voices and votes. All those African American Senators and Congressmen in the earlier Reconstruction era? By 1901, that was completely done with, and there wouldn't even be any other African American representatives from Southern states in Congress at all for over seventy years. Voter suppression really did its job.

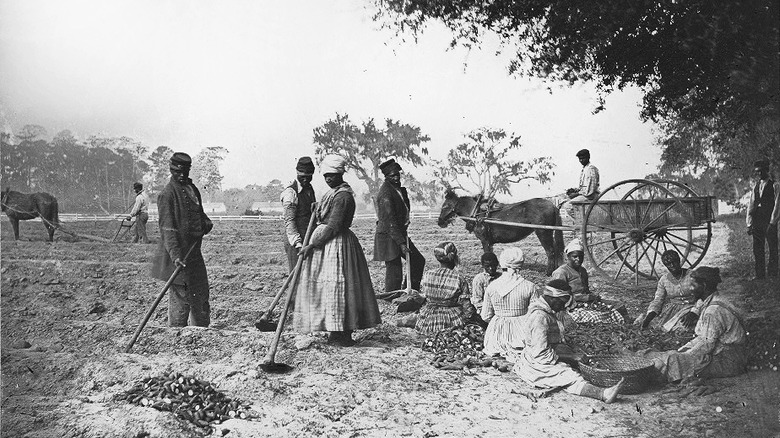

With blacks pushed out of public offices and politics, they were instead pushed into something like pseudo-slavery through the development of sharecropping; Frederick Douglass put it as "the determination of slavery to perpetuate itself, if not under one form, then under another" (via New York Times). And, to really top it all off, in 1883, the Supreme Court actually decided to strike down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 (you know, the one that protected African Americans' rights). It feels accurate to say that Douglass was right to call Redemption "the defeat of emancipation."

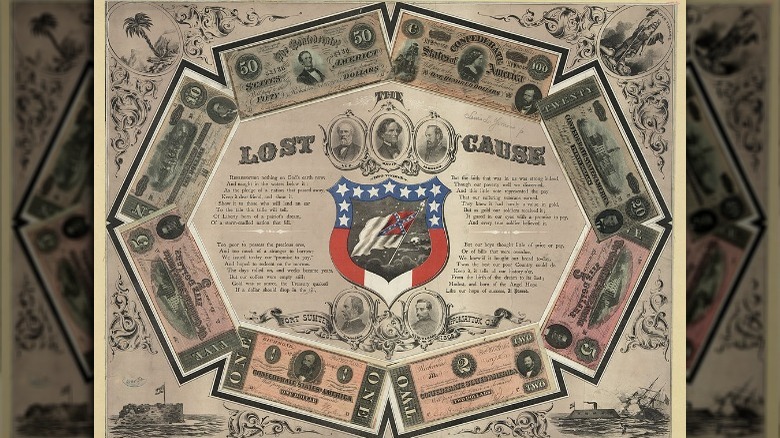

'The Lost Cause'

Here's where we start getting to those more long-term effects of this whole Redemption movement. You know the entire "it's about states' rights" thing? Yeah, that's sort of where the "Lost Cause" comes in.

In a nutshell, Redemption undid all of the work of Reconstruction, turning white supremacy in the South back into the norm. With that being the state of affairs, it almost seems like a natural step for the South to rewrite the actual narrative of the Civil War, and that's exactly what this whole "Lost Cause" thing is. It's a way for people to glorify the Confederate South, and it's a mythos that, per The Atlantic, is still around well into the 21st century.

A major part of that is the argument over what caused the Civil War in the first place. Most people would say it was slavery, but the Lost Cause mythos says that slavery was only a small part of the problem. This wasn't about owning slaves, but about the idea that states should be allowed to govern themselves: states' rights, and all that. And the people who fought for the Confederacy weren't racists, but just honorable men trying to protect their communities. Besides, according to the Lost Cause, slavery wasn't that bad anyway. Even the term "Civil War" gets thrown out in favor of "the war of Northern aggression," because it absolves the South of any blame, allowing the Lost Cause to stand on ideas of heritage and pride.

The messy legacy of Southern Redemption

The fall of Reconstruction and the rise of Redemption is an event that really sent ripples out through history, and in quite a few pretty negative ways overall.

When it comes to ideology and the glorification of the Confederacy via the Lost Cause, well, just look to the South over the years. Groups like the Daughters of the Confederacy have worked hard for decades to ensure that the Civil War is taught in schools in the "proper" way. And what's the "proper" way? The one that erases African American achievements, insists that the Confederacy and slavery really weren't so bad, and deifies the KKK (via Facing South). And that's not an old problem. That kind of curriculum has been the norm in some states well into the 21st century. (Then there's the whole thing of what to do with Confederate statues, which is an entire discussion on its own, and one that's still going on as of writing, per NPR).

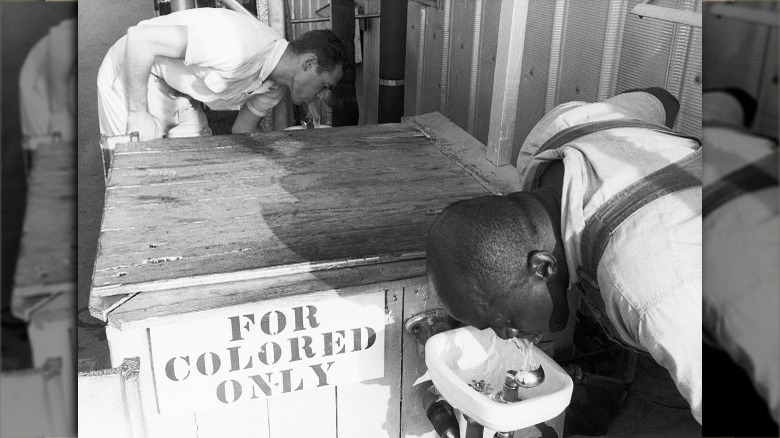

Or there's also just the entire Jim Crow era, which can be attributed to Redemption, as outlined in the New York Times. Pushing African Americans out of places of power allowed for decades of segregation. With that came the Black Codes, which just made life even harder for African Americans, and the development of sharecropping and lynching, a couple other staples of Jim Crow (via History). And if that wasn't enough, there was also the resurgence of the KKK; need more be said?