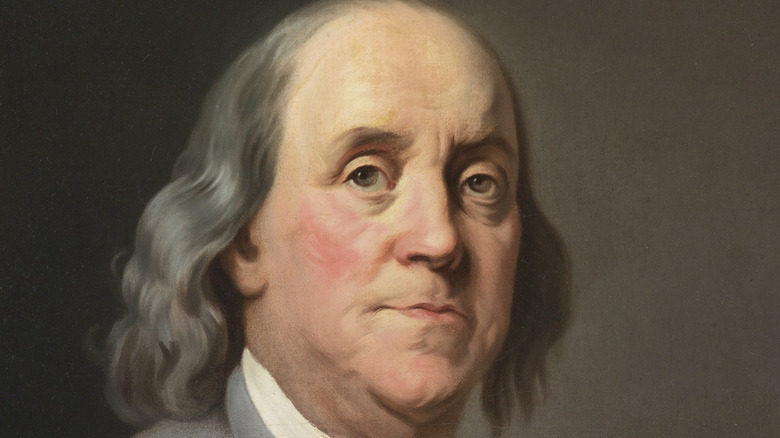

This Is What Ruined Benjamin Franklin's Relationship With His Son

William Franklin was born on February 22, 1730, to an unknown mother and future founding father of the United States of America, Benjamin Franklin. Openly acknowledged by his father, the younger Franklin was raised by his father's common-law wife, Deborah Reed. As a child, he helped the polymath elder Franklin with many projects, including writing Poor Richard's Almanac, assisting with science projects, including the famous key and kite experiment that proved lightning was electricity, and learning printing, as reported by the American Battlefield Trust.

When he was just 16 years old, William Franklin enlisted in King George's War and was eventually made captain. He went to London, England, to study law in 1759 where he fathered a child and married Elizabeth Downes. When he returned to the North American colonies, he became royal governor of New Jersey thanks to his father's networking. He was the last and longest serving royal governor of New Jersey. During his time in office, William improved the state's infrastructure and chartered what became Rutgers University, New Jersey's state university.

After decades of following in his father's footsteps, William Franklin had decidedly different views than Benjamin when it came to the American Revolution. William was a staunch Loyalist who thought the colonies should remain under British rule. Per Monticello, in August 1775, Benjamin Franklin traveled to New Jersey to convince William to join the American rebellion. William declined; he thought the best chance for the country's success lay with remaining British colonies and thought most colonists would feel the same way.

William Franklin was a devout British Loyalist

Despite his father's pleas, William Franklin remained a Loyalist, even giving a speech to the New Jersey legislature in which he urged them to reject the newly formed Continental Congress. "You have now pointed out to you, Gentlemen, two Roads — one evidently leading to Peace, Happiness, and a Restoration of the public Tranquility — the other inevitably conducting you to Anarchy, Misery, and all the Horrors of a Civil War," he said, according to Kean University.

Per Monticello, Franklin continued reporting American revolutionary acts to the British, which eventually led to his arrest; the Continental Congress declared him "a virulent enemy to the people of this country and a person who may prove dangerous." William Franklin was placed under house arrest in Connecticut. When he violated the terms of his arrest, he was put in solitary confinement in a cell for prisoners sentenced to execution. When he learned that his wife was gravely ill, he pleaded with George Washington to be allowed to go free and see her, to no avail. Eventually, suffering from illness himself, he was exchanged with another prisoner and allowed to go to New York. In 1777, he sailed for England, where he lived until his death in 1813.

Benjamin Franklin refused to forgive his son

Throughout William's imprisonment, Benjamin Franklin did nothing to help his son. William hoped to reconcile with his father when Benjamin Franklin arrived in Paris, France, as a peace commissioner and stayed from 1781 to 1785, but refused to apologize for his Loyalist views.

In August 1784, as reported by Monticello, he wrote a letter to his father hoping "to revive that affectionate intercourse" but emphasized that he was happy with his decision to have "uniformly acted from a strong sense of what I conceived my duty to my king." Per The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Benjamin Franklin refused to forgive his son for what he perceived as personal disloyalty, writing "Nothing has ever hurt me so much ... as to find myself deserted in my old age by my only son, and not only deserted but to find him taking up arms against me." He returned to the United States in 1785 without seeing William, and the two never met again.