Ella Baker: The Untold Truth

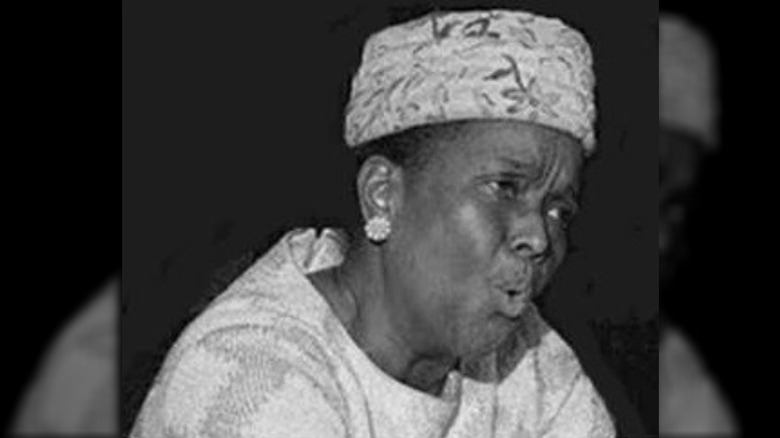

Ella Baker always knew that when working together, people were capable of phenomenal things. And although many at the time considered her to be too idealistic and radical, Baker spent her life bringing people together and fighting with these ideals in mind.

SNCC chair Charles McDew said that Baker taught people how to find value in "everyone's opinions" and constantly underlined the importance of everyday people rather than upholding "messianic leaders." And while some may describe Baker as a Civil Rights leader, she herself eschewed that label, maintaining instead the idea that her work was a part of a larger effort where everyone had something worthwhile to contribute when it comes to grassroots organizing.

Baker once said, "you didn't see me on television, you didn't see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come. My theory is, strong people don't need strong leaders." And with her organizing efforts, Baker proved her own theory. She frequently rejected top-down hierarchy in favor of community organizing, and although not all those in the Civil Rights Movement agreed with her methods, Baker continued to organize, and her work ended up inspiring countless others. This is Ella Baker: The untold truth.

Ella Baker's early life

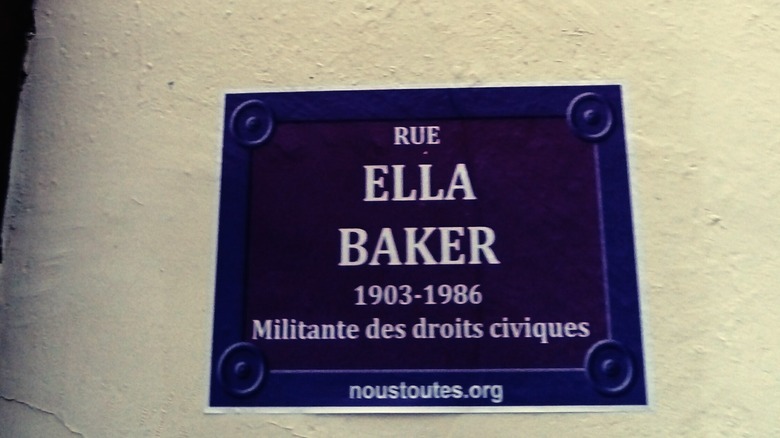

Ella Josephine Baker was born on December 13, 1903, in Norfolk, Virginia to Georgianna Ross and Blake Baker. Her mother worked as a school teacher, midwife, and health care worker, while her father was a waiter for a ferry line, according to the New York Public Library. When Baker was eight years old, the family moved to Littleton, North Carolina to be closer to her maternal relatives.

The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights writes that when she was young, Baker would listen to her grandmother tell stories about how life was like under enslavement, including an incident when her maternal grandmother "Bet" Ross was whipped because she refused to marry someone that her enslaver had chosen for her. But SNCC writes that Ross refused to let the hard labor she was subjected to break her spirit, and would attend "every celebration on the plantation, dancing until the early hours of the morning to show that her spirit remained unbowed." These stories greatly affected Baker and inspired her lifelong fight against racism.

Baker attended Shaw University, where she was the youngest contributor to the campus newspaper, while simultaneously working as a chemistry lab assistant and a waitress. After graduating as valedictorian in 1927, Baker moved to Harlem in New York City, writes Black Past.

Getting into activism

In Harlem, Ella Baker started to get involved in community organizing and social activism. Black Past writes that in 1927, Baker joined American West Indian News as a journalist, and three years later became office manager for the Negro National News. In 1930, Baker also co-founded the Young Negroes Cooperative League with George Schuyler, becoming its national director the following year. According to the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, the YNCL sought to "develop black economic power through collective planning."

As the Great Depression hit, it became clear to Baker that hard work and perseverance weren't enough to create financial stability, especially for Black Americans, and so she channeled her energy into investigating unfair labor practices. Women & The American Story writes that during one of these investigations in 1935, Baker got a job as a domestic worker in order to research the inequity that Black women workers were faced with.

This research led to Baker's piece "The Bronx Slave Market," co-written with Marvel Cooke. In "Ella Baker, 'Black Women's Work' and Activist Intellectuals," Joy James writes that their piece "maintained [that] economic justice for poor and working-class African Americans [was] the primary objective for black political struggles." In their piece, Baker and Cooke also revealed that many white working-class women who employed Black women as domestic workers often set their clocks back a couple hours in order to cheat Black women out of their wages.

Joining the NAACP

After working at the YNCL, Ella Baker was recommended to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) by Schuyler and in 1941, she joined as a field secretary. According to Women & The American Story, Baker spent the following three years traveling around the Southern states raising money and recruiting members for the NAACP. And although the work was considered to be dangerous, Baker ended up building a "massive network for the NAACP." Black Past writes that Baker was the NAACP's "most effective organizer" and helped create numerous new branches across the South. Baker worked as the director of branches, but in 1946, she resigned from the NAACP because she was unable to get the organization to focus on the influence of grassroots organizing, according to The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute.

Baker rejoined the NAACP in 1952 as president for the NAACP's New York chapter, but by the following year, she temporarily resigned in order to run for the New York City Council on the Liberal Party ticket, Barbara Ransby writes in "Civil Rights in New York City." Baker had previously run for city council in 1951 as well, but she lost both times.

Throughout this time, Baker maintained her focus on grassroots organizing and recruited community members to get involved in issues such as police brutality and school desegregation. Inspired by the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Baker also organized In Friendship, a group that helped fight Jim Crow laws.

A brief history of the NAACP

The NAACP was founded in 1909 by a group of 60 Black and white activists, including Ida B. Wells, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Mary White Ovington. The organization was founded in response to the Springfield holocaust of 1908 that claimed the lives of at least nine Black people in Springfield, Illinois and turned thousands of Black residents into refugees, according to Black Past. The NAACP's website writes that a national office was established in New York City the following year, and by 1913, branch offices were created in several cities. By 1919, there were over 300 local branches and with membership numbering up to 90,000.

One of the main goals of the NAACP was to eradicate lynching. The NAACP report "Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1919" is credited with "drastically decreasing the incidence of lynching" but efforts to make lynching a federal crime repeatedly failed. And as of 2021, lynching is still not a federal crime in the United States, according to Daily Journal.

The NAACP was also incredibly influential with its legal advocacy and was part of several significant legal victories such as Guinn v. States (1915) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1952-1954). But these successes were frequently met with violence, such as the 1951 murder of NAACP field secretary Harry T. Moore and his wife Harriette V. S. Moore, whose murder is considered one of the first assassinations of the Civil Rights Movement.

Working with the SCLC

Ella Baker moved to Atlanta, Georgia in 1958 in order to help Martin Luther King Jr. organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute writes that Baker was in charge of organizing the SCLC's Crusade for Citizenship, which was aimed at enforcing voting rights for Black Americans.

According to Women & The American Story, Baker was skeptical about the organization, but she took on the role of its grassroots organizer. However, Baker soon became discouraged with the SCLC. They weren't too receptive towards the idea of community organizing, which they saw as too radical, and the fact that she was a "determined woman" seemed to rub the men in the organization the wrong way. Andrew Young writes that "The Baptist church had no tradition of women in independent leadership roles, and the result was dissatisfaction all around."

Ultimately, Baker didn't think that big speeches and praying were enough, and she believed that smaller grassroots groups could be more powerful than a one-time march. She also repeatedly reminded King that the Black women in the movement were "unappreciated and unrecognized" despite the fact that they were often "doing the hardest work." The New York Public Library writes that despite Baker's efforts, the Crusade had limited success. Later in her life, Baker came to believe that the failures of the Crusade were "due primarily to internal resistance from both the members and the leadership of the organization."

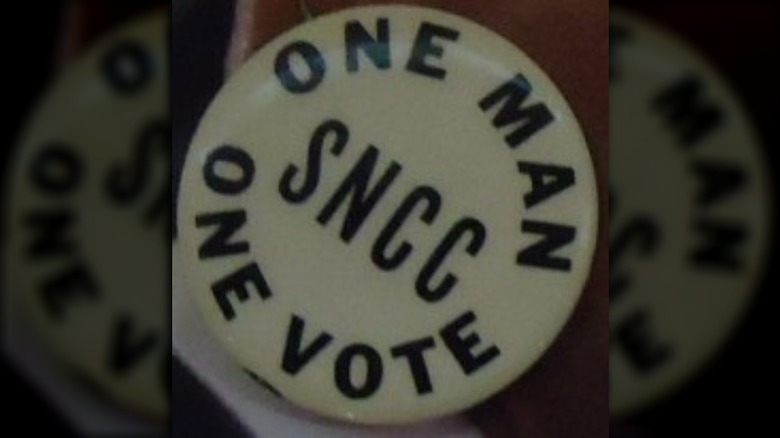

Leaving the SCLC for the SNCC

After hearing about the February 1960 sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, Ella Baker realized that young student activists had the same vision she had, so she decided to join her efforts with theirs. According to the SNCC, Baker convinced Martin Luther King Jr. to give $800 towards what would become the founding conference of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). And although King had wanted the students to simply become "an SCLC student wing," Baker encouraged the young activists to create their own organization.

HBCUSTORY writes that Baker was known as the "Godmother of the SNCC," and was incredibly influential towards influencing the Black college student movement. But according to the New York Public Library, despite founding the organization, Baker never held any sort of official position with the SNCC. But she worked with the organization as a "political adviser, role model, fund-raiser, intellectual and political mentor." With the network Baker had established with the NAACP, she was also able to connect the SNCC with other activists and resources across the country.

But at the end of the day, the organization was run by the student activists. Women & The American Story writes that when she was asked to weigh in, Baker would ask questions instead of seeking to provide them with answers. For example, when the SNCC organized Freedom Summer in 1964, in order to bring national attention to racism in Mississippi, Baker supported the initiative and "only spoke up when disagreements pulled the conversation off course."

Misogyny in the Civil Rights Movement

The bottom-up organizing of the SNCC wasn't the only thing that inspired Ella Baker to leave the SCLC for the SNCC. The SNCC writes that compared to other organizations during the Civil Rights Movement, women were included and weren't kept from leadership positions. This isn't to say that sexism didn't exist within the SNCC, but compared to organizations like the SCLC, it didn't serve to keep women in the background.

But while fighting against race-based oppression, many organizations in the Civil Rights Movement, like the SCLC, continued to uphold gender-based oppression. And MSNBC writes that even during the 1963 March on Washington, women's voices were actively excluded. When Gloria Richardson went to speak during the rally, the microphone was taken away from her after all she managed to say was "Hello." Even Rosa Parks was shocked that actress Josephine Baker hadn't been allowed to speak. And after the rally, the delegation that met with President Kennedy was made up solely of men.

According to "Women in the Civil Rights Movement," Black women were even told to take an active step back for the sake of allowing the men to lead. Lawrence Guyot, for example, told a group of Black women that included Fannie Lou Hamer, Victoria Gray, and Annie Devine "that the time had come for them to step back and let the men come forth."

Organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

In April 1964, Ella Baker worked with the SNCC and helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party with Fannie Lou Hamer, which sought to challenge Mississippi's all-white Democratic Party. According to Yale, Baker ended up giving the keynote address at the MFDP's founding convention, and was integral towards organizing the MFDP's challenge to the Democratic Party at the 1964 National Democratic Party convention. Women & The American Story writes that Baker was the one responsible for finding the cheapest hotel rooms for the organization in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

According to The New York Times, the 1964 Democratic Party convention was "contentious." Sixty-eight delegates from the MFDP came to the convention and tried to convince the Credentials Committee that "Black Mississippians were systematically excluded from the regular state Democratic Party," writes the SNCC. Even President Lyndon Johnson tried to keep their testimonies off the air. Eventually, the Democratic Party leaders tried to come up with a "compromise" and said that they would allow the MFDP delegation two seats for Aaron Henry (pictured) and Edwin King. But the MFDP rejected this, with Hamer saying, "We didn't come all this way for no two seats."

Baker set up offices for the MFDP in Washington, D.C. and worked from there in preparation for the convention, and after the convention, she moved back to New York City.

Working with the SCEF

From the early 1960s, Ella Baker also started working with the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF), a civil rights organization that also worked closely with the SNCC. According to the SNCC, Baker's relationship with Anne Braden, one of the faces of the SCEF, was directly responsible for the two organizations supporting one another.

According to an interview Baker gave in 1968, she initially joined the SCEF as a special consultant, since she was "weary of certain kinds of responsibility" and this way she could have a more flexible role. Baker also refused payment from the SCEF, since she believed that "they could use that money for hiring some more active young people." Baker also never had any sort of paid relationship with the SNCC, per Yale. As a consultant, Baker's role was mainly to attend to whatever issues came up and to offer the resources she had after years of community organizing. At times, this meant being a "sounding board," a "bridge," and "at points something of a comforter."

Ultimately, the goal of the SCEF was to instill in white Southerners the idea that they should care about what was happening to Black Southerners. And for Baker, this project was very successful, when considering "the increased amount of dedication on the part of young whites to work in that vein."

Supporting other women activists

Throughout her years as an activist, Ella Baker constantly made sure that she was supporting the other women in the Civil Rights Movement. In addition to supporting the defense of Anne Braden, who was targeted by HUAC, according to Labor History in 2:00, Baker was also involved in the Free Angela! Movement, which sought to free imprisoned activist Angela Davis.

Great Black Heroes writes that Baker traveled across the United States, advocating for the release of Davis, who was arrested on murder charges, but was actually being targeted for her activism and Communist views. In 1972, Davis ended up being acquitted after representing herself in court for an all-white jury.

Clio History writes that Baker consistently underlined the work that was done by women activists, saying that "The movement of the fifties and sixties was carried largely by women." Baker maintained this conviction by also being involved in a number of women's groups, including the Third World Women's Alliance and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), Sylvia Lovina Chidi writes in "The Greatest Black Achievers in History."

Ella Baker's final years of activism

Ella Baker remained involved in activism till her very last days and maintained her ideology of resisting all forms of oppression. According to History 101, Baker supported Puerto Rico's calls for independence, joining the Puerto Rican Solidarity Committee, and actively spoke out against apartheid in South Africa in her later years.

Women & The American Story notes that Baker consistently fought to "bring people together in the fight for freedom." And although she didn't agree with rejecting white allies, she didn't keep the SNCC from moving in that direction. And although Baker was dismayed when the SNCC dissolved, she continued to volunteer towards a variety of civil and social justice causes.

According to an interview Baker gave in 1977, in her life, she was also involved in the WPA Workers' Education Project, which sought to provide jobs for people who were dealing with any kinds of social issues. And in working with the Workers Education Project, Baker was able to interact with a wide variety of ideologies. Baker found that despite the differences in ideologies, they were able to have dialogue and learn from one another. "I think it was those who had the desire to search for knowledge, to search for at least some semblance of understanding, and were accepting."

On December 13th, 1986, Baker passed away in her sleep on her 83rd birthday.

Influence in the Civil Rights Movement

Ella Baker's influence in the Civil Rights Movement and beyond cannot be understated. In addition to the immense amount of time she put into her activism, she influenced countless people in the younger generation, including Stokely Carmichael, Diane Nash, and Bernice Johnson Reagon. Carmichael himself said that "The most powerful person in the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s was Miss Ella Baker, not Martin Luther King," according to Civil Rights Teachings. And Reagon's song "Ella's Song" was written as a tribute to Baker. The Key writes that the piece even included Baker's own words.

Time Magazine writes that one of the reasons that Baker's name isn't as well-known as that of Rosa Parks or Dr. King's is because Baker never made being in the spotlight her goal. Instead, Baker said that she "found a greater sense of importance by being a part of those who were growing." But at the end of the day, the desire for the men of the movement to silence and speak over the women ended up prevailing.

But for Ella Baker, the movement wasn't about being a leader. She often said that "strong people don't need strong leaders," and she showed the world that she was an incredibly strong person.