The Best TV Shows Of The 1950s

Television is approaching its 100th birthday. On January 13, 1928, the first-ever publicly available television broadcast was sent out from Schenectady, New York, and the world would never be the same.

Of course, it took some time for television to become a cultural force. First of all, a lot of people had to purchase televisions. Second of all, we had to get through a little something called World War II before we could focus on the technology that would eventually make Kim Kardashian mysteriously famous. So it wasn't until the 1950s that TV began producing what we think of as TV programs today.

What's amazing about that era of TV is that far from being an awkward beginning period, the whole decade is rich with surprisingly good shows covering a wide range of genres and styles. This is in part due to developing existing work — many of the classic TV shows of the 1950s were adapted from existing, popular radio shows —and in part due to the exciting creative possibilities the new medium offered artists.

As a result, that decade produced shows that still rank as some of the greatest TV ever made, and many shows from that era are still regularly broadcast and appreciated by viewers of all ages. Here are the best TV shows of the 1950s.

I Love Lucy: Inventing the future

There aren't too many TV shows you can legitimately call iconic, but "I Love Lucy" is one. Starring real-life spouses Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, this show basically invented the sitcom, and then perfected it, and finally set a bar that every ensuing sitcom would be expected to clear.

To give some idea of just how popular "I Love Lucy" was from the moment it debuted in October, 1951, Hollywood Reporter notes that within six months it was the No.1 show in America, with 11 million people watching every week — for context, there were only 15 million TV sets in the country. NPR explains that what often gets lost in discussions about the show's influence is how Desi Arnaz more or less created the modern-day business of television, and that was after he and Lucy fought to convince network executives that an interracial couple should be allowed on national television. Arnaz pioneered the multi-camera setup still used by many sitcoms today and insisted on filming it on 35mm film. When the networks balked at the cost, Arnaz brilliantly offered to pay for it in exchange for owning the show outright — another first for artists in the business.

Life observes that "I Love Lucy" was also surprisingly subversive. Lucy's stories feature her rebelling against societal constraints, engaging in a sort of stealth-feminism that was acceptable because it was funny, but still asked the question: Why can't a woman do these things?

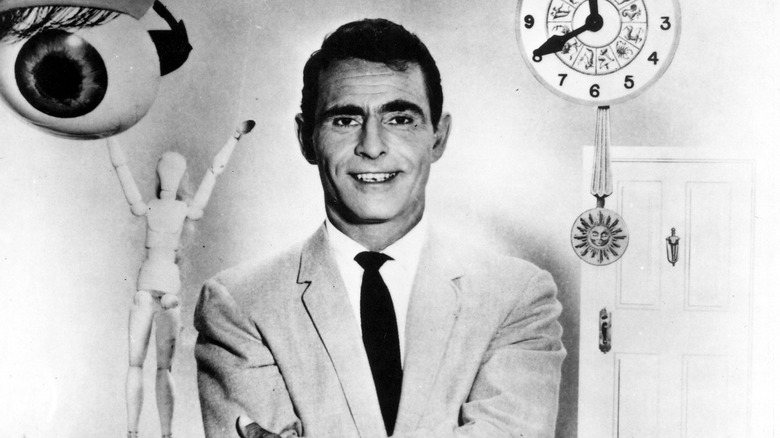

The Twilight Zone: Iconic ambition

There's simply no more iconic opening credits in history. Nor a more iconic opening narration than Rod Serling's clipped recitation of "There is a fifth dimension, beyond that which is known to man ... This is the dimension of imagination. It is an area which we call ... the Twilight Zone."

"The Twilight Zone"'s influence can be measured in how often — and how recently — it is rebooted, re-imagined, and re-introduced. That cultural durability is a testament to the writing. Rod Serling was a thoughtful man who wanted his work to address big issues. The New York Times reports that in an earlier project, Serling watched helplessly as a script he wrote to address the racist murder of Emmett Till was butchered by network censors, and that he was determined to retain creative control over "The Twilight Zone." That led to stories that address racism, nuclear holocaust, and a host of other uncomfortable subjects in surprising ways. Black Youth Project explains that stories dealing with race and racism in "The Twilight Zone" stood out in the otherwise sanitized TV screen of the 1950s and 1960s.

What makes "The Twilight Zone" great is the stories. In an interview with Forbes, Serling's daughter Jodi recalls that Serling ignored commercial considerations in favor of artistic ones. He chose to work in the science fiction and fantasy genres to mask the progressive messages he wanted to convey, because he knew the sponsors would resist. But it's the clever twists and deeply imagined characters that have made this show a perpetual classic.

The Honeymooners: Surprisingly timeless

"The Honeymooners," which History reports first graced TV screens way back in 1951 as a sketch on Jackie Gleason's "Cavalcade of Stars," is still being aired on broadcast TV in some markets, making it one of the most durable shows to come out of the 1950s.

It's so embedded in our culture, in fact, that it's easy to forget that the classic sitcom format of the show (Gleason revived it during the 1960s occasionally in an hour-long format) only exists as 39 half-hour episodes that aired from 1955 to 1956.

The Chicago Tribune proposes one reason for the show's greatness and staying power: it was rooted in reality. Gleason based the show on real people he knew. Knowing that their relationship could be seen as bleak, Gleason specifically chose the title to emphasize to audiences that there was real love between bus driver Ralph Kramden and his wife, Alice. "The Honeymooners" was one of the first comedies to depict working-class people as opposed to affluent folks in the suburbs. It didn't do well in the ratings in its initial run, but its more realistic approach to American life is one reason it's remained a staple of pop culture ever since.

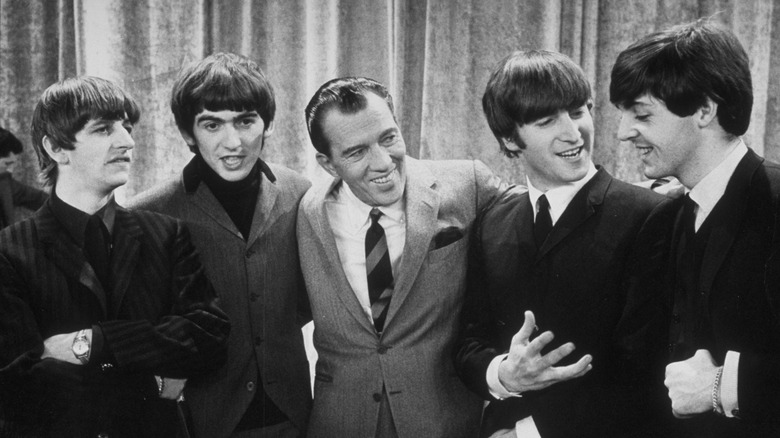

The Ed Sullivan Show: A little bit of everything, all of the time

If you enjoy watching shows like "America's Got Talent," you owe Ed Sullivan a debt of thanks. His classic variety show, which debuted in 1948 but became a cultural mainstay during its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, wasn't the first of its kind, but it proved to be the most influential. Variety reports that over the course of its 23-year run, "The Ed Sullivan Show" became one of the most important places to promote an act. The defining feature of Sullivan's show was the juxtaposition of hugely different acts, from ballet and opera to the Beatles and Bob Hope.

USA Today explains how influential Sullivan was in the music business. He actively promoted Black musicians, and energetically booked musical acts he didn't like or even understand, because it was important to push boundaries. NPR reports that Sullivan worked to introduce his audience to a wide range of culture, seeing it as his responsibility to broaden people's tastes.

The end result was a show that buzzed. ThoughtCo explains that the viewing public came to trust Ed Sullivan's taste in much the same way people held their breath watching "American Idol" to see what Simon Cowell would say about an act, and Sullivan's formula is still being used on TV today.

Gunsmoke: Original grit

The western was a staple of 1950s television. While many of those westerns, such as "Maverick" and "The Rifleman" were perfectly fine, only one stands out as culturally important: "Gunsmoke." The show debuted on radio in 1952, then on television in 1955, where it ran for the next two decades.

The Baltimore Sun notes that "Gunsmoke" is significant in part because it was just the second western series written for adults (after "The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp"). AV Club reports that the writers took that very seriously and set about avoiding as many hoary old western cliches as they could — starting with the very first episode, in which the main character, Marshall Matt Dillon, is gunned down while enforcing the law in Dodge City.

In other words, far from a corny 1950s western, "Gunsmoke" was in many ways the original "gritty" reboot, taking the sanitized "Roy Rogers"-style Old West that people were used to seeing on TV and replacing it with the violent, sometimes unpleasant place it actually was. Crucially, the show depicted violent men (and even women) dealing with the consequences of their actions. That level of writing maintained the show through 635 episodes and left it a classic of 1950s TV.

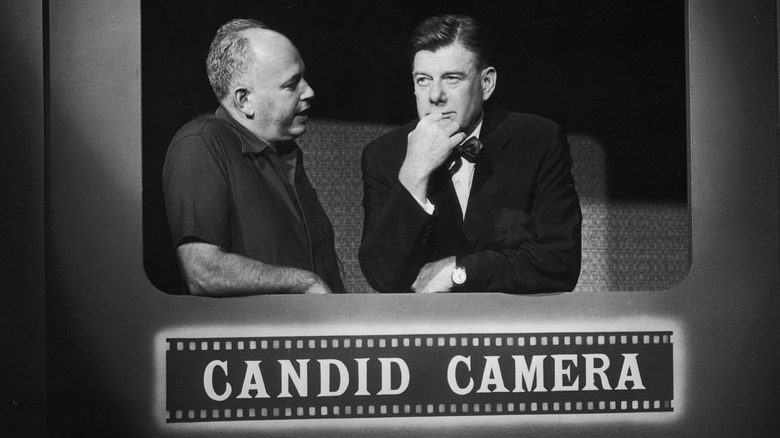

Candid Camera: The original reality program

Beginning life on the radio as "The Candid Microphone," Allen Funt's practical joke-based show moved to television in August 1948. It finally changed its title to the familiar "Candid Camera" in 1949. This was the first example of reality television, and pretty much established the genre. For that alone, the show will always have a place in TV history.

Creator Allen Funt became interested in the psychology of human behavior while working as a research assistant at Cornell University. Television Academy Interviews reports that the elaborate setups for the show's pranks were very difficult — the early camera equipment was difficult to conceal, the lighting rigs were impossible to conceal and had to be explained away by various excuses, and about 50 scenarios were filmed for every five that made it to air.

The Cornell Chronicle explains that one aspect of the show that ensures its legacy is the fact that academics value the material and frequently use it to study human behavior, something Funt encouraged, donating the non-commercial rights of the show to researchers. Audiences didn't think about that, of course — they simply enjoyed the hilarity of watching real people navigate unusual circumstances, making it one of the most popular shows of its era. Its influence is obvious in shows like "Punk'd," which replicate the formula with new twists.

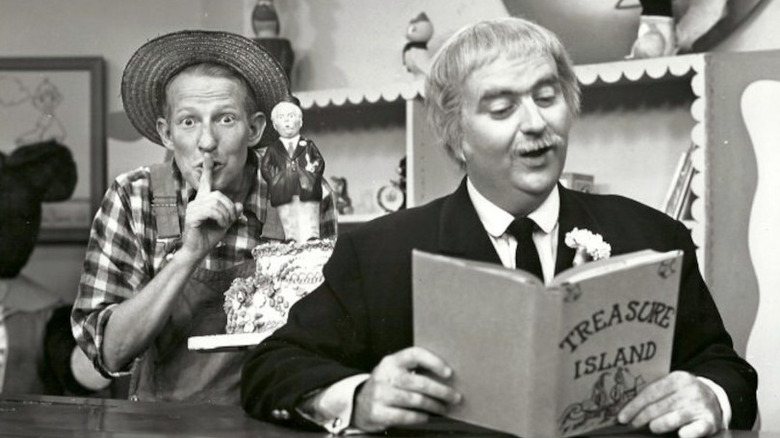

Captain Kangaroo: High quality kids' TV

As explained in "Children's Television, 1947-1990," when "Captain Kangaroo" premiered in 1955 there wasn't much quality programming specifically for children. Launched by Bob Keeshan, who portrayed Clarabell the Clown on "The Howdy Doody Show" before launching "Captain Kangaroo", the show ran for 29 years, becoming the longest-running live action children's show in history.

Academic Jeana Lietz notes that Keeshan envisioned "Captain Kangaroo" as an antidote to low-quality shows for kids, pushing to incorporate educational aspects in the content. FiftiesWeb explains that Keeshan took steps to insulate his young audience from marketing, pioneering the use of "bumper" segments that made it clear advertisements weren't part of the program and forbidding sponsors he thought to be inappropriate for kids. The show eventually won six Emmy Awards and two Peabody Awards.

The show never had a fixed format — each episode featured cartoons or guest appearance from a range of regular characters, held together by Keeshan in his iconic captain's jacket with oversize pockets. The show was a fixture for several generations of kids, and remains a touchstone in kids' programming. The Wrap reports that in 2018, actor Mark Wahlberg announced a plan to reboot the show.

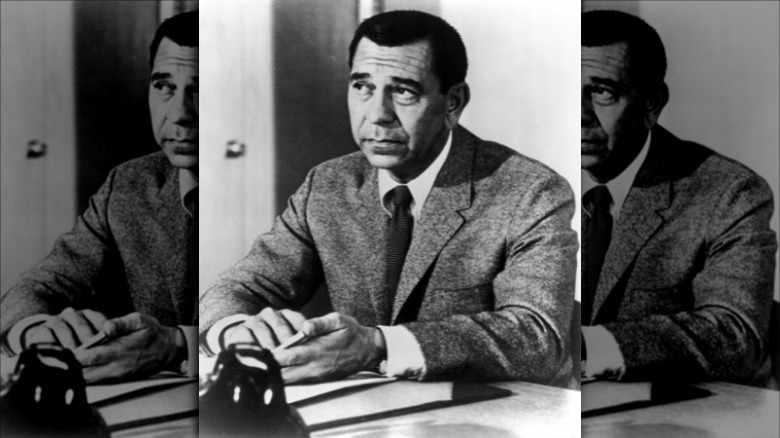

Perry Mason: Setting the bar for TV lawyers

Perry Mason, a defense lawyer who often acts more like a grizzled noir detective, was created by novelist Erle Stanley Gardner, who published 82 novels about the character. The stories and characters have been adapted many times over the years, but one of the most iconic efforts remains the television show staring Raymond Burr.

Debuting in 1957, Smithsonian Magazine explains that not only was the show the first time many Americans saw a version of what actually happens inside a courtroom, and what lawyers actually did, it also basically created the courtroom procedural. Just about every show featuring a lawyer, from "L.A. Law" to "Law and Order," owes a debt to this 1950s drama. The Los Angeles Times explains that the success of "Perry Mason" spurred a rush of imitators that stole just about everything from the original, from its story beats to its trademark confession at the end of just about every episode.

In fact, some of the more ridiculous cliches of lawyer shows, like incredibly permissive judges sternly warning the attorney to "get to the point" while allowing enormous latitude that would never fly in a real courtroom, can be traced back to this show.

Your Show of Shows: Perfecting sketch comedy

Sketch comedy was a staple of television almost from its very beginning — one of the biggest hits of the early 1950s, Milton Berle's "Texaco Star Theater," was essentially a sketch comedy show any modern fan of "Saturday Night Live" would recognize. But, as AV Club notes, Sid Caesar's "Your Show of Shows" would perfect the format and push every boundary. The writer's room for "Your Show of Shows" became the model for every sketch comedy show that followed because Caesar and his collaborators insisted on infusing every sketch, no matter how silly, with a back story and a sense of character — something that was revolutionary for TV comedy at the time. Britannica explains that some of the sketches in "Your Show of Shows" are regarded as important evolutionary steps towards the development of the situation comedy format we love today.

"Your Show of Shows" was also notable for the way it pushed female comedians to the forefront, most notably co-host Imogene Coca. Vulture reports that Caesar and Coca were so popular by 1954 that the network decided to cancel "Your Show of Shows" not because of dipping ratings, but in order to give Caesar and Coca separate shows and get twice as much ad revenue. As well as having the talented Coca in front of the camera, the show used a number of female writers, a surprisingly progressive notion in the early 1950s.

Dragnet: The original copaganda

The Atlantic puts is pretty succinctly: "Dragnet" was "the most influential police procedural ever." The producers of the show, which debuted in 1951, worked incredibly closely with the Los Angeles Police Department to not only achieve verisimilitude but to shape the stories they told and the way they depicted police. To say the show always showed police in a good light would be drastic understatement — the show was copaganda before the word existed.

But the audiences of the time didn't know that, or care. "Dragnet" was a monster hit. Timeline explains that in 1955 the show had 16.5 million viewers in a nation with 37 million sets, and that an additional 6 million people were listening to the "Dragnet" radio show. The show's influence was so strong that AV Club notes it returned for a second run eight years after being canceled, returning to television in 1967 and running an additional three years.

The Wrap explains that "Dragnet"'s quality scripts and pretensions towards reality, the implication that it was showing people the truth of law enforcement and that "only the names have been changed to protect the innocent," continue to inspire gritty cop shows year after year. While modern shows like "Law and Order" stay away from direct cooperation with police departments, instead relying on news articles, the basic template established by "Dragnet" continues to be followed today.

Playhouse 90: Serious live drama

It's hard to overstate how ambitious "Playhouse 90" was. The UCLA Film & Television Archive reports that the anthology drama series debuted in 1956 with an explicit goal of pushing television's boundaries. The idea of putting on live dramatic performances, written by some of the best writers, and attracting big star acting talent, was a fresh one at the time. Television was born with a reputation for being dumb entertainment for the masses, and "Playhouse 90" was one of a series of programs marketed as more highbrow, serious, and high-quality.

As noted by AV Club, the show's second episode, "Requiem for a Heavyweight," put it on the map and almost single-handedly ensured its legacy. Written by Rod Serling, the drama starred Jack Palance as an aging boxer contemplating his life after his last fight. It won several Emmy Awards and was the first television script to win a Peabody Award.

"Playhouse 90" produced 134 episodes. While the quality varied over the years, the fact that it presented long-form drama performed live remains a remarkable achievement. The live nature of the performances led to some embarrassments, like the time an actor dropped a prop baby, which proceeded to bounce down some stairs while the actors stood frozen in shock, but the primary legacy of the show is the fact that it legitimatized the idea that TV could be great.

Leave it to Beaver: Secretly subversive

When people talk derisively about bland, blindingly white 1950s television, they usually mention "Leave It to Beaver." And for good reason. As Considerable explains, in many ways the show, which debuted in 1957, fits the bill. The Cleaver family is a white, affluent, suburban clan led by a wise and caring father and managed by a poised and affectionate mother. Traditional values were espoused, and every episode ended on a happy note.

But what set "Leave It to Beaver" apart was how well-made it was. The show was very funny — AV Club calls it "one of the best sitcoms of its era" — with a consistency of characterization that rivals any other situation comedy ever made. The show allowed its characters to grow and evolve in a way most sitcoms didn't, with elder brother Wally eventually growing up and going off to college.

Most importantly, "Leave It to Beaver" was a secretly subversive show. The Washington Post explains that this is best demonstrated by the character of Eddie Haskell, whose insincere politeness and constant trolling made him an antihero of sorts. It was a complex character used in complex ways on what was ostensibly a mild-mannered situation comedy. The show took its teenage characters seriously, and that made it a surprisingly effective sitcom that still holds up today.