What It Was Really Like To Live Under Apartheid

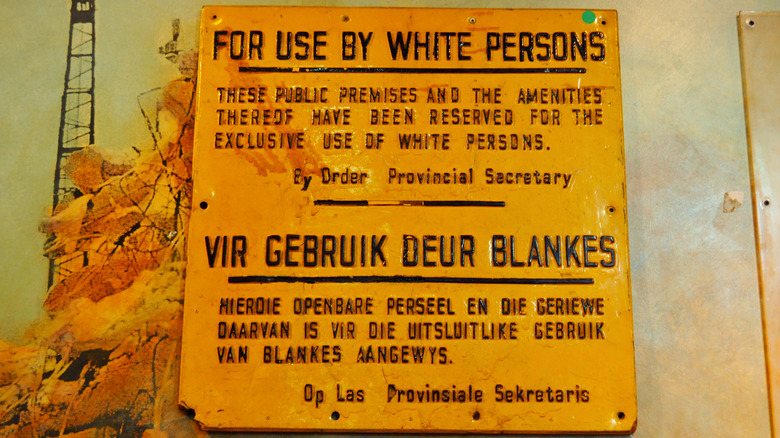

Apartheid, which means "apartness" in Afrikaans, was a government mandated system of racial segregation amongst the people of South Africa from 1948 to 1994, in which a set of laws governed where people could live, work, learn and worship based on the color of their skin. The system of governing was established roughly 300 years after the Dutch first established Cape Colony, now called Cape Town, in 1652, according to History. Over those hundreds of years, British and Dutch forces were involved in a sort of tug-of-war over the colony, with native tribes like the Zulu people and the Khoikhoi fighting to retain control of their homeland, per the BBC and South African History Online.

Over time, diamonds and gold were discovered, making the southern African land even more covetable, and eventually the white colonists chipped away at taking over the territory and infringing on the freedoms of the native people. In 1934 The Union of South Africa parliament declared the nation to be a "sovereign independent state," cutting ties with British rule, and in 1948 the National Party came into power, initiating their new policy of apartheid.

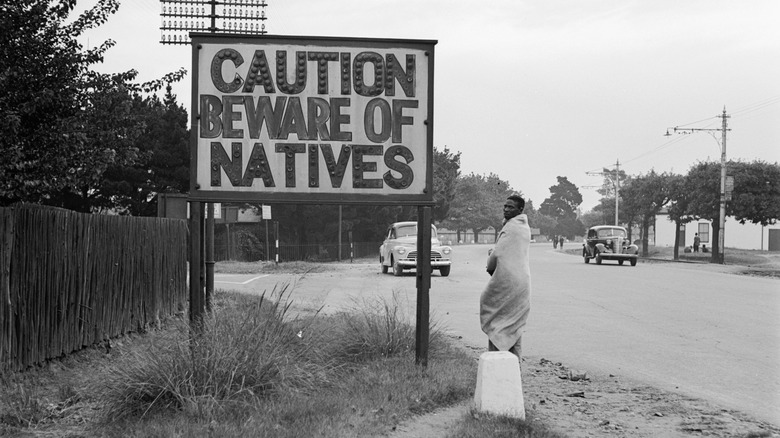

According to History, segregation and white supremacy had already been in place, but the National Party took it to the next level by enacting many laws over the next decade and beyond, and officially classifying humans as either native (Black), colored (mixed), Asian (Indian or Pakistani) or white.

The National Party claimed apartheid was good for everyone

The architects of apartheid sold the ideology as being "in harmony with such Christian principles as justice and equity. It is a policy which sets itself the task of preserving and safeguarding the racial identity of the white population of the country; of likewise preserving and safeguarding the identity of the indigenous peoples as separate racial groups," per a pamphlet issued by the National Party in 1947 before they were voted into power.

Allegedly, the effort to separate people by their race would benefit all, the National Party promised, writing in the pamphlet, that apartheid would mean " ... opportunities to develop into self-governing national units; of fostering the inculcation of national consciousness, self-esteem and mutual regard among the various races of the country."

What's more, they even claimed things would go one of two ways depending on whether or not apartheid became the law of the land. If it didn't, it would amount to "suicide on the part of the whites." But if the apartness came to pass, The National Party said it would "preserve the identity and safeguard the future of every race, with complete scope for everyone to develop within its own sphere while maintaining its distinctive national character, in such a way that there will be no encroachment on the rights of others, and without a sense of being frustrated by the existence and development of others."

Lies. History would see a different version of that spin.

Race was subjective

According to the Gandhi-Luthuli Documentation Centre, one of the first laws passed under apartheid was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949, outlawing marriage between white people and people of any other race. That law was followed in 1950 with the Immorality Amendment Act, which legislated that no white person could have sex with anyone of a different race outside of marriage.

That same year, the Population Registration Act was enacted. That meant that every single person living in South Africa had to register their race, and if there were any question about someone's racial authenticity, it would be decided by the Race Classification Board.

Per the Sunday Times Heritage Project, the board basically just eyeballed it, and what race you were deemed directly affected what rights you would have. There were whites and there were the rest, which were eventually broken down into at least six different groups. Race was determined by the darkness or lightness of skin, the curliness of hair, facial features and lineage.

Those classified as white were affected by this race distinction too. The Sunday Times Heritage Project tells stories of people who grew up classified as white losing their status based on who they hung out with, or if they were investigated when a question came into play about their ancestry. People who were married as the same race could then be breaking the law if one of them was deemed a different race than their spouse. That actually happened.

The South African government worked against unity amongst the people

Apartheid is complicated. Besides the segregation of the four main categories — white, Black (native), colored (mixed from the days before mixing was outlawed) and Asian (mostly Indian), there was even a sort of segregation within the groups, most notably within the Blacks who consisted of several tribes that lived in the region long before European settlers came along.

According to the University of Jyväskylä, South African leaders emphasized the differences between all the groups, including the various groups within Black society, so that they would focus their ire on each other rather than on the government and the system that oppressed them all. Per South African History Online, keeping native groups at odds with each other meant they were less likely to unite against the central government. After all, there were a lot more Blacks than whites.

Under apartheid, African — or Bantu — groups were relegated to living on 13% of the land in South Africa, while whites kept the mineral-rich areas and the cities. According to South African History Online, more than 3.5 million people were made to leave their homes and jobs from 1960 to 1994 to move to the Bantustans where they were relegated to living in poverty, with no political agency. Blacks could not own land. They could not vote.

Blacks, Indians or coloreds were not free to move out of their prescribed territories. They were not permitted to even be in other races' areas unless they were employed there. And they better have proof.

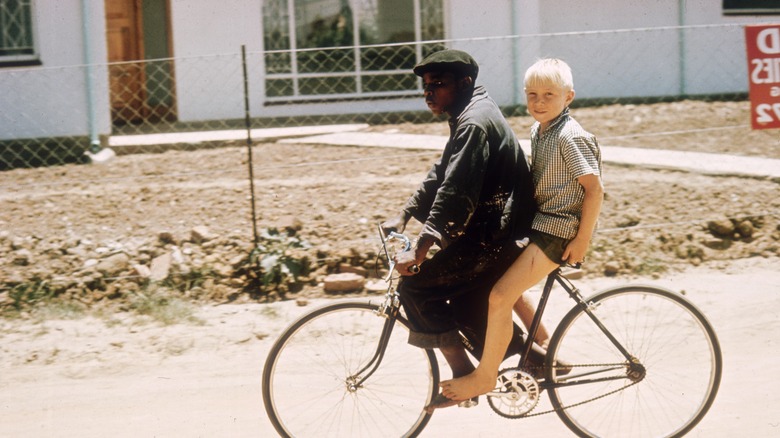

Bantu children were not deemed worthy of European educations

According to a 1978 New York Times article titled, "Under Apartheid: Life in One Black Family," which chronicles a couple of weeks in the life of a family living in the sprawling Black township of Soweto, the lives of its residents were distinctly ruled by poverty. Multi-generational households all crammed into small homes that usually lacked electricity and/or indoor plumbing. Workers rose early or worked nights, catching busses or trains to clean and service the white parts of South Africa as laborers, maids, cooks, and gardeners.

Common problems amongst the oppressed Blacks included violence, unplanned pregnancies, alcoholism and unemployment, according to The New York Times. The population was rising faster than homes were being built, leaving young adults with few prospects for getting out on their own. Most people practiced some kind of religion. Whether they embraced the Christian religion of their European oppressors, clung to their customary tribal beliefs, or practiced some combination of the two, many found comfort in spirituality.

However, like all other things, Christian houses of worship were, of course, segregated by race, as were the schools and universities children were allowed to attend. According to South African History Online, Bantu children, or Blacks, were given minimal education, designed for their futures as servants and laborers. Law decreed that "it is no avail" for them to be educated beyond that. Why would they need to know about history, art, or science if their roles were just to serve whites?

Apartheid ended, but its legacy lingers

The human rights abuses under apartheid were something the world could not ignore, and over time nearly every nation in the world had some kind of anti-apartheid organization, whether it be a government, religious groups, universities, trade unions and civil organizations, according to South African History Online.

According to the U.S. Department of State, uprisings against the South African government usually did not end well for those who stood against the National Party. In 1960, 69 unarmed people were killed and 186 were wounded when South African police opened fire on Black protesters in Sharpeville. On June 16, 1976 high-school students in Soweto began protesting for better education, and more than 600 people were killed, according to the BBC.

By the 1980s the system of apartheid had eroded from both internal strife and external forces, such as the condemnation of other nations, which affected the nation's "revenue, security and international reputation," per the U.S. Department of State. In 1990, Prime Minister F.W. de Klerk, of the crumbling National Party, released political prisoners, such as anti-apartheid leader and icon Nelson Mandela, freed after 27 years of incarceration.

Four years later in 1994, Mandela was elected South Africa's first Black president. While apartheid had technically ended, the ramifications of the past still linger today. According to the Associated Press, President Cyril Ramaphosa said in 2019, 25 years after apartheid ended, "Ours is still a deeply unequal country."