The Olympics: Most Famous Athlete From Every State

While it's no secret that Olympic athletes are representing their entire country on the global stage, there's a little more to it with U.S. athletes. They're not just flying the flag of their country, but they're representing their state, too.

And there's nothing like cheering for the athlete capable of almost superhuman feats of strength, skill, and sport when they're from your home state. There's an undeniable sense of pride that comes with cheering on the hometown hero, and when they're on a global stage, that's what the Olympics is all about.

The Olympic Games started in Greece, sure, but they were banned for somewhere around 1,500 years before being reinstated in the form of the modern games we know and love today. They started on April 6, 1896, and since then, each and every U.S. state has sent one of their own to represent their country. Let's look at the most famous athlete from every state.

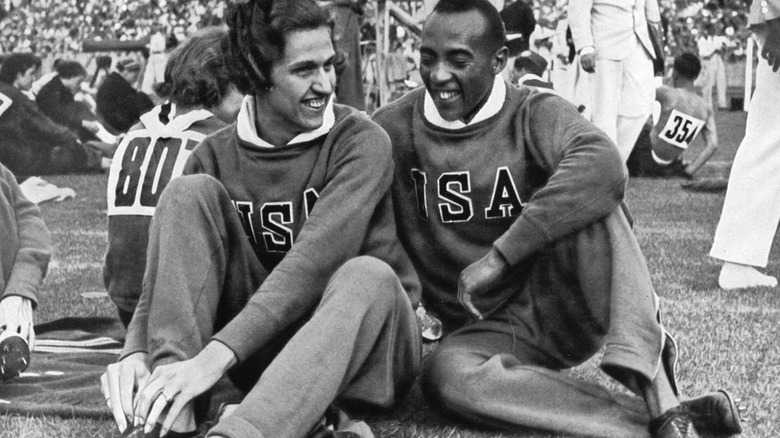

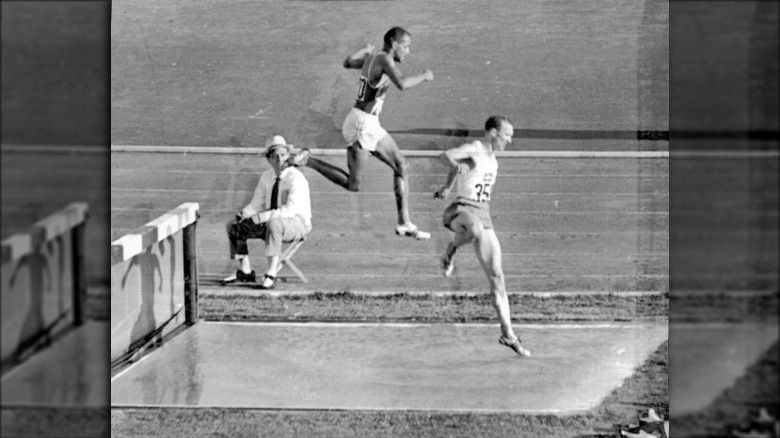

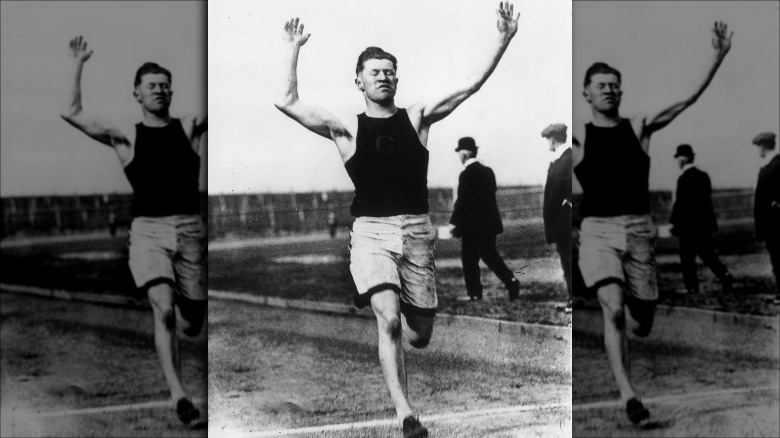

Alabama: One of the country's great track stars

Jesse Owens was born in Alabama in 1913, and History Today describes his hometown as a place of "poverty, geographical isolation, and quiet desperation." The youngest of 10 children, he skated through school, was instantly recognized for his skill in track and field events, and went on to represent the U.S. in the most controversial Olympics of all: Hitler's 1936 Berlin games.

The oft-told tale that Hitler snubbed the Alabama athlete wasn't the least bit true, and he actually sent him an autographed picture. In spite of Owens' medals and world records — History says he was the first American to take home four golds in track and field events — he made no secret of the fact that he was treated worse at home than he had been abroad. The world leader who did snub him? Then-president Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

When Owens returned, he toured the nation as a speaker motivating the next generation of athletes. He died in Arizona in 1980.

Alaska: The state's first medalist

In 1984, Kristen Thorsness secured her place as a sporting legend in her home state of Alaska, by becoming the first Alaskan to win an Olympic medal. It was in a sport that she never thought she had a chance in, either: after being told that she was too short and too light to be an effective rower, she made everyone who ever said it to her do a little eating of their words.

She told Forbes that even though they went into the Games favored to win, that just made it infinitely more stressful. It was hot, the race was delayed, but once they brought it home, she said, "I had never seen an Olympic gold medal before, and there stood a woman holding a tray with nine of them ... I wore my medal under my shirt for the remaining week of the Games."

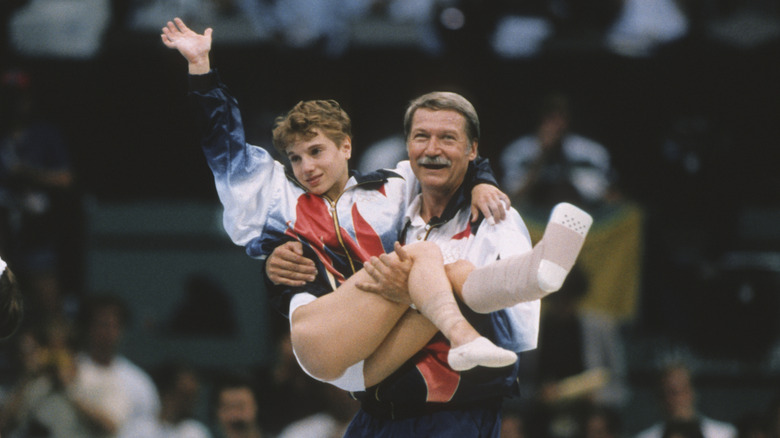

Arizona: Competing through injury

In 1996, Kerri Strug was competing as a part of the USA's gymnastics team when she badly injured her ankle. The team, however, needed another vault and a higher score, so the 18-year-old gymnast limped out and ran it again. This time, it was nearly perfect — it earned the gold for the team, and three torn ligaments for her.

The injury meant that she couldn't continue, and the Tucson, Arizona native has said (via Esquire), "I look back on that moment and I was devastated I didn't get to compete further."

While the Netflix series "Athlete A" looked into a culture of abuse and toxic pressure to compete through agonizing injury, she said, "From my perspective, in order to be the best on a world-class stage, you have to train incredibly hard. Do they sometimes take it to another level? Possibly, but that is what it requires."

Arkansas: Setting world records

There was never any doubt. It was clear just how good a runner Jim Hines was from the time he went through his high school career completely undefeated in the 100- and 220-yard dashes, says the Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

He has given any state a lot to be proud of. After breaking national high school records, he became known as one of the country's best sprinters. He was, says the BBC, in a class of new athletes called "power runners" — runners who relied on pure muscle for their speed.

When he headed to the Mexico City Olympics in 1968, he became the first man to run the 100-meter dash in less than 10 seconds. Hines returned home with gold, and went on to a career as a professional football player and dedicated his later life to helping the homeless as well as abused women and children.

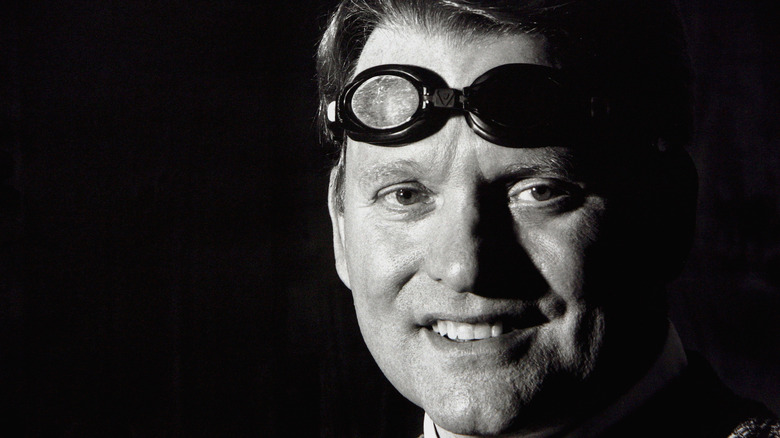

California: The country's controversial diver

Greg Louganis headed to his first Olympics when he was 16 years old, took home a silver medal, and even though he missed the 1980 Games (which were boycotted by the U.S.), he took two golds in 1984, and in 1988, became (via AP) the only diver to ever sweep gold at consecutive Olympics.

There was, however, controversy. Shortly before the 1988 Olympics, he tested HIV positive.

At the time, there was a massive stigma against HIV/AIDS, and Louganis didn't tell Olympic officials of his diagnosis. That became a major concern when he hit his head on the diving board during one of his dives and required four stitches. He still took the gold, but History says it took another seven years before he stepped forward to say that he knew he was HIV positive. He and his coach decided no other divers were at risk, and ultimately, no one was affected.

Colorado: Four gold medals in a single Olympics

Swimmer Amy Van Dyken's six Olympic gold medals over the course of competing in just two Games is made even more impressive by the fact that childhood allergies and asthma had left her struggling for breath to the point where she couldn't swim the length of a pool until she was 12. It was just a few years later that the Englewood native was named Colorado Swimmer of the Year, and five years after that, it was off to the Olympics.

It was Atlanta's 1996 Games where the Colorado Encyclopedia says she became the first female U.S. athlete to take four gold medals in a single go, and while her record-setting appearances were incredible, she's managed to continue doing good long after her retirement. She was involved in a severe accident in 2014, which severed her spine and left her paralyzed. Since then, she has become active in charities and fundraisers benefiting others who have suffered spinal injuries.

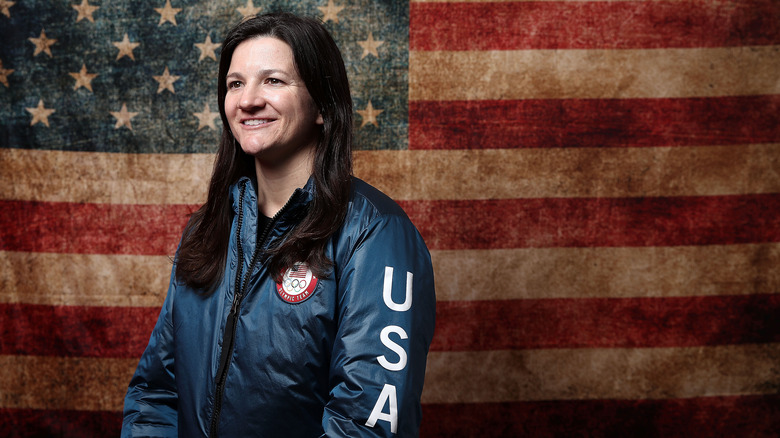

Connecticut: Paving the way for women in hockey

Ice hockey superstar Julie Chu played 129 games for the Harvard Crimson, scored 88 goals and had a further 196 assists (via Union Athletics). By the time she took to the ice for Harvard, the Fairfield, Connecticut native had already become the first Asian American woman to represent the U.S. on the Olympic ice hockey team.

During her Olympic career she took home a bronze and three silver medals (via the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum), and she would go on to not only set more records and earn more recognition for her skills on the ice, but there's a brilliant footnote to her Olympic career. Chu, captain of the U.S. ice hockey team, and three times, they went to the finals and faced off against Canada and their captain, Caroline Ouellette. The two rival captains went on to marry, and have not only eight Olympic medals between the two of them, but a daughter as well.

Delaware: The state's own basketball superstar

Missing valuable experience as a high school student might seem like it would be a major setback for an aspiring Olympian, but Delaware's Elena Delle Donne didn't let it impact her in a negative way — instead, she took her 12 missed games and her diagnosis of Lyme disease and not only went on to the Olympics, but to be an official ambassador for the Lyme Research Alliance.

She's also involved with the Special Olympics, as a tribute to her sister — who is deaf, blind, and diagnosed with autism and cerebral palsy.

She headed to Rio in 2016 and took home a gold with Team USA, and has since made waves in the WNBA as well. BolaVIP says, however, that in spite of being credited as a key player in 2016, she was going to be missing out on the 2020 Olympics — instead, she was recovering from back surgery.

Florida: Swimming's greatest ambassador

Winter Haven, Florida's Rowdy Gaines is proof that sometimes, age doesn't really matter. While most Olympians might start their chosen sport when they're super young, but Gaines first hopped in the pool to compete when he was 17. He would go on to win three Olympic gold medals, and it's a count that likely should have been higher, if he hadn't been forced to skip the 1980 Games because of the US's boycott. Instead, that was about the time he set a whopping 11 world records.

He qualified again for the 1996 Olympics — the oldest to ever do so, and after being diagnosed with a neurological disorder. But, instead of swimming, Gaines opted to switch to being a commentator instead of a competitor. He's been a familiar face with NBC Sports for a long time, and Team USA says he's still considered "Swimming's Greatest Ambassador."

Georgia: Basketball legend

The University of Georgia has only retired the numbers of five jerseys, and one is the Number Five that belonged to Teresa Edwards. At the same time she was playing for the university as a Lady Bulldog, she became the youngest player to head to the international stage.

She said (via the University of Georgia), "I came from the small town of Cairo, Georgia, I didn't grow up dreaming about the Olympics. People hate to hear it, but it's true ... I had to grow into my patriotism and understand the weight of those three big, bold letters on my chest."

She had plenty of time to do so, taking home medals in first the 1984 Olympics, then the next four Olympic Games after that. The Basketball Hall of Fame says that she was the first American to compete in five Olympics, took home four gold medals, and was one of the most decorated team athletes of the games.

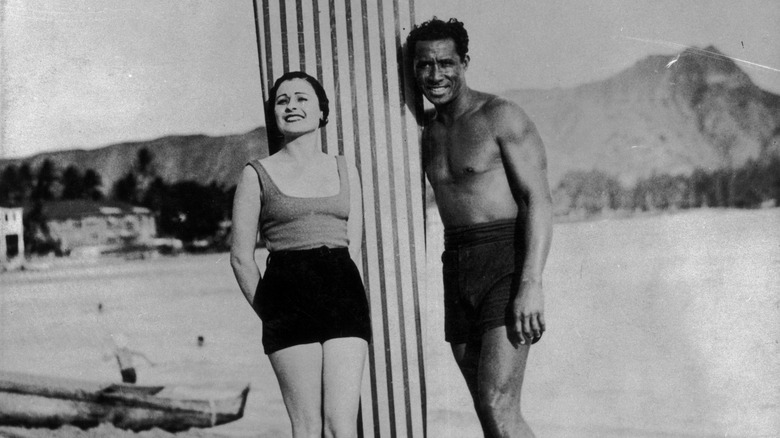

Hawaii: The father of surfing

When Duke Kahanamoku was born in 1890, it was still known as the Kingdom of Hawaii. It wasn't until he was 30 years old that he competed in the 1920 Olympics, set a few world records along the way, and took home the gold in the 100-meter freestyle. And then — after being woken up from a nap — he jumped in the pool again. This time, he was with teammates, and they took the gold in the 4x200 relay.

While there's no denying he was an incredible swimmer, that's not even what he's most famous for — and it's not why there are statues of him in far-flung locations from Australia to Los Angeles. He's considered the "father of modern surfing," and spent much of his life traveling and promoting the sport. He died in 1968 after suffering a heart attack, and his ashes were scattered in the ocean he loved.

Idaho: Overcoming adversity one hill at a time

If there's anything more beloved than a phenomenal athlete, it's an athlete that struggles through difficulties to come out on top. Alpine skier Picabo Street's first Olympic appearance in 1994 saw her taking the silver, and her run for the gold in 1998 was plagued with setbacks.

She missed a year of training after a bad fall, and had just two months to prepare before Nagano. In that week, she suffered through another fall that was so bad she was knocked unconscious, and a subsequent concussion. Still? That time, Street — whose first name is a Sho-Ban Native American word that means "shining waters" — got the gold.

She explained to ESPN: "You put a roadblock in front of me, and I'm going to find a way to either get around it, over it, under it, or plow right through it if I have to."

Illinois: The country's greatest female track star

Jackie Joyner-Kersee was born a stone's throw — and the Mississippi River — away from St. Louis. The East St. Louis, Illinois native grew up collecting sand in potato chip bags to build her own long jump pit, and said (via the Los Angeles Times): "I knew that eventually, if we had continued to do things right, something good was going to happen."

Her first trip to the Olympics saw her walking away with a silver in the heptathlon, which wasn't a bad deal — especially considering she's only recently started throwing the javelin.

Then, she started breaking world records, and broke her own record in the 1988 Olympics. She went back again and again, before officially retiring in 2001 to become an advocate for children, mental health, and improving the educational and athletic landscape of her hometown. In 1998, she explained: "When I leave this earth, I want to know I've created something that will help others."

Indiana: Honesty about post-Olympic struggles

Indiana freestyle skier Nick Goepper went to two Olympics — in 2014 and 2018 — and took a silver and a bronze for Team USA. In addition to making a name for himself in other competitions like the X Games, he's also been candid about the difficulties that he — and many other athletes — suffer through after the Olympics.

In 2018, he spoke openly (via the Los Angeles Times) about the sense of crisis that he had felt after the Sochi Olympics. "I just really had no plan after Sochi. I was ... kind of just flying into this void, and three weeks after the Olympics, I was like, 'What am I doing?'" His downward spiral into despair left him with suicidal thoughts, and he's also spoken about the help he's gotten. He returned to skiing, and as a volunteer with mental health organizations like 1n5 and Building Hope.

Iowa: America's gymnast

When Shawn Johnson appeared on "Dancing with the Stars" in 2012, America got another chance to cheer for her. The USA Gymnastics star from West Des Moines, Iowa was a fan favorite at the 2008 Olympics, where she won one gold and three silver medals.

Since then, she's been open about the difficulties faced by young athletes. In 2021, she spoke openly (via Best Life) about a huge problem she'd suffered through alone: a lack of nutritional guidance and psychological support. Pressure to perform and look a certain way — thin — led to the then 16-year-old Johnson developing an eating disorder. While she said that at the time, she'd felt it was worth it, in hindsight, "When I started to starve myself and jeopardize my performance, but still win a gold medal, that is probably one of the worst things that could have happened."

Johnson has since retired from gymnastics, and says, "I was so happy and so free, to be not a part of that world anymore."

Kansas: The fastest man in the world

Kansas native Maurice Greene is one of the fastest men on the planet. His list of awards and records is long, says World Athletics, and includes one Olympic bronze, one silver, and two gold medals.

His first Olympic appearance was in Sydney in 2000, and while he was determined to repeat his gold medal appearances, his 2004 Athens appearance left him with a bronze and silver. Days before he was set to compete, he spoke with The Guardian — it hadn't been an easy road. The sprinter had seemingly fallen from being an unstoppable whirlwind to not quite the best, and it wasn't until after his world records started being broken that he went public with what had happened. He'd been riding his motorcycle on an LA freeway when he was hit by a car, and he'd broken his leg. A rushed recovery was blamed, and he officially retired in 2008.

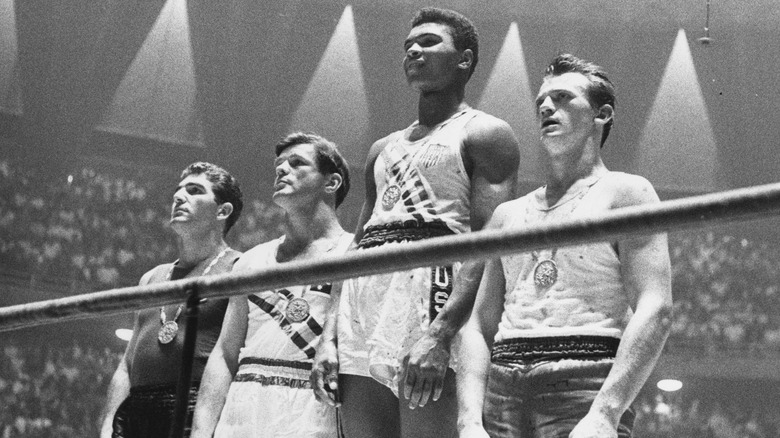

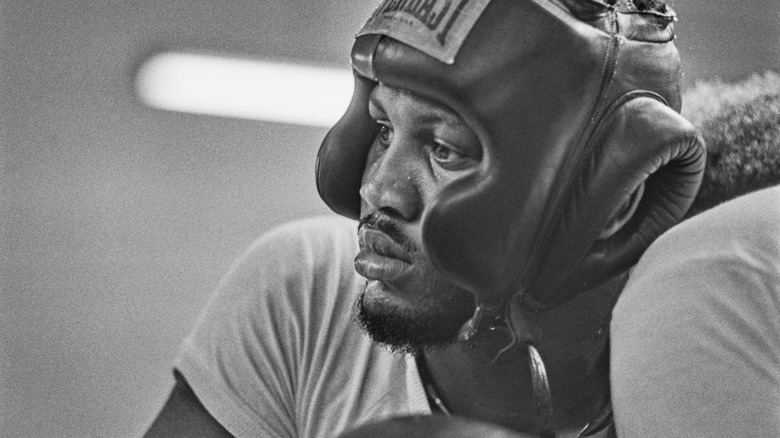

Kentucky: The Greatest

Even those who don't know anything about sports know the name Muhammad Ali, and while the Olympics is an end goal for many, it ended up being just the start for the man who was known as Cassius Clay when he headed to Rome in 1960. It was there that he took the gold after defeating the three-time European champ in the international ring, and he was just getting started.

The Kentucky Historical Society says that Ali was guided down the path of boxing after a police officer suggested that he channel his anger not at the thief that stole his bike, but at an opponent in the ring. It worked, and just four years after the 18-year-old fighter took the Olympic gold in Rome, he knocked out Sonny Liston to become the world's heavyweight champ.

Ali was named a United Nations Messenger of Peace in 1998, and spent much of his later years in humanitarian endeavors such as speaking against Apartheid.

Louisiana: Once the fastest woman in the world

Evelyn Ashford's first trip to the Olympics came in 1976, when she headed to Montreal. She'd return to three more games and take home four gold medals and one silver, making her one of the most decorated American track and field athletes to ever compete.

She was a world record-holder, too: According to World Athletics, she held the record between 1983 and 1988, and was known as the fastest woman in the world. Born in Louisiana to an ever-moving military family, it wasn't until her teens that a teacher at her California high school asked her to race his fastest track star — which she did, completely and thoroughly.

She's described running like this: "When it is right, it feels like absolutely nothing. It feels like you are floating on air, you're concentrating so hard ... Every time I run, I try to run for that feeling of absolutely nothingness."

Maine: An early marathon star

Maine native Joan Benoit's first love was skiing, and it was only after breaking her leg and being prescribed running as a way to rebuild her strength that she decided it was her sport — and at the time, she felt she needed to hide it. She told the BBC: "This was a time when there really weren't a lot of runners, period, let alone a lot of woman runners ... I would hide out there and do my running alone because I was trying to shed my tomboy image I had."

Benoit estimates that over the course of her career, she's clocked more than 150,000 miles. Included in that was the gold at the 1984 LA Olympics, running in the first women's marathon not long after undergoing knee surgery.

And she didn't stop: decades later, she was still running in events like Chicago's marathon commemorating the 2,500th anniversary of Athens' Battle of Marathon.

Maryland: Counting gold medals by the dozen

There's no denying that Michael Phelps is one of the most successful American Olympians of all time — the numbers just don't lie. His career started in 2000, when he took part in the Sydney Olympics at just 15 years old. Over the course of the next five Games, he took home 28 medals — and 23 of them were gold (via USA Today).

Born in Baltimore in 1985, Phelps has been open about his struggles, saying (via LDRFA): "I had a teacher tell me that I would never amount to anything, and I would never be successful. So, it was a challenge and it was a struggle, but for me, it was something I'm thankful that happened. And I'm thankful that I am how I am."

After retiring following the 2016 Rio Olympics, Phelps went on to found a line of swimming equipment, and establish the Michael Phelps Foundation, which has a focus on health and water safety. He's also a board member and advocate for the mental health organization Medibio.

Massachusetts: A record-setting female swimmer

Is it possible to have so many Olympic gold medals that the excitement wears off? If anyone knows the answer to that, it's Team USA swimmer Jenny Thompson. She walked away from her appearances at the 1992, 1996, 2000, and 2004 Olympics with eight gold medals, three silver, and one bronze — making her the most decorated female Olympic swimmer (and most decorated female American Olympian) ever.

Born in Danvers, Massachusetts, her first gold medal win came when she was just 14 years old — at the Pan American Games. While a trip to Seoul in 1988 wasn't in the cards, it's safe to say she made up for it later — and along the way, she set a whopping five world records.

Thompson has since retired (via USOPM), and the graduate of Stanford University and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons is now a pediatric anesthesiologist.

Michigan: America's first ice dancing champions

Meryl Davis and Charlie White both hail from Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and when the ice dancers first came together in 1997, their coaches saw something magical. The partnership absolutely worked, and won the silver in the 2010 Olympics, and the gold in 2014. That, says Stars on Ice, makes them the first American ice dancing champions, and it's a huge deal, especially considering how much the U.S. has historically struggled on the ice. Both have since been inducted into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame (via The Detroit News), and although they have retired from competitive skating they're still active in the sport.

Davis is a founder and chair of the youth organization Figure Skating in Detroit, while White has gone on to be a skating commentator, coach, and is active in the youth charity Classroom Champions. White says, "We have felt the responsibility ... in the end, to always be grateful."

Minnesota: The honest hero of the ski slopes

The Guardian calls ski racing legend Lindsay Vonn "the most human of champions," when, in 2018, she headed back to the Olympics after spending years in the headlines for other reasons — starting with the catastrophic (and high-profile) meltdown of her relationship with Tiger Woods.

There were also injuries, too: Torn ligaments and broken bones made it look unlikely that she'd make it back to reclaim her Olympic glory with Team USA, and 2010 remained her biggest showing. By 2018, Vonn was speaking candidly about the toll the sport was taking on her, and she was lauded for her honesty in talking about the mental and physical struggles of being a world-class athlete.

Vonn was back on the world stage again for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, only not as a competitor. A well-known dog lover, she partnered with Allianz and their Support Dog Squad to bring a little canine love, affection, and support to the athletes of the Olympics (via Insider).

Mississippi: Flight to freedom

When Willye B. White died of pancreatic cancer in 2007, The New York Times mourned the death of an outstanding athlete. White had been born in Mississippi in 1939 and described her childhood like this: "I started chopping cotton when I was 10. You could chop for a whole week and never finish a row. I got paid $2.50 a day for 12 hours. The only way I could get any recognition was through sports. Sports gave me an escape."

She started running at the same age, and by 1956, she was headed to the Olympics — where she took home a silver. She held records in the long jump for around 20 years, was the first U.S. Track star to compete in five Games, and after her retirement, went on to work as first a practical nurse, then a health administrator. Now inducted into 11 different halls of fame, she considered her greatest achievement "was my flight to freedom."

Missouri: Controversial before her time

Helen Stephens was a track star who took home two Olympic gold medals from Hitler's 1936 Berlin Olympics, setting records for the 100-meter and 400-meter relay. Historic Missourians says that while that was it for her Olympic showings, she did run the 100-meter again — when she was 68 years old, and she still came within 4 seconds of her Olympic time.

Stephens was famous for another reason, too. According to The Guardian, she was one of the athletes that was caught up in the debate over "gender fraud." Stephens beat a Polish runner named Stella Walsh in the 100-meter, and became the first Olympic athlete to be forced to undergo an on-site "gender test." The Sydney Morning Herald says that was essentially walking naked in front of designated judges. Stephens passed the test and retained her gold, but in light of more recent conversations about transgender athletes, her story is more relevant than ever in the 21st century.

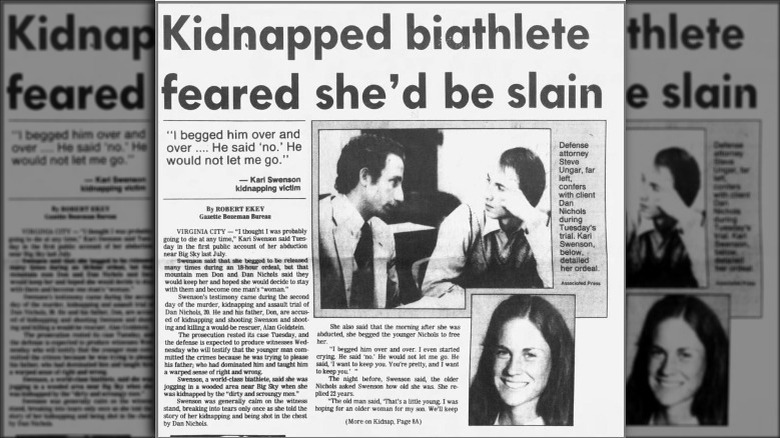

Montana: When tragedy derails an Olympic push

Kari Swenson was raised in the wilds around Bozeman, Montana, so it's not entirely surprising that she was a wildly successful biathlete, excelling in every part of the sport. Her connection with the Olympics is a little different: According to ESPN, her performance as part of the 3-person biathlete relay at the women's world championships in 1984 was part of a massive push to get the women's biathlon included in the Olympic Games. The event would finally be added in 1992, but what happened in the meantime was nothing short of shocking.

It was also in 1984 that Swenson was kidnapped while out running. Her abductor was Don Nichols, a self-proclaimed "mountain man" who grabbed the then 22-year-old as a bride for his son. Nichols shot and killed a friend of Swenson's who was helping to look for her, and she, too, was shot and — says Patch — thought dead from her severe chest wounds.

Nichols was paroled after serving 32 years of his 85-year sentence, and while the incident left Swenson unable to compete, she's still credited with blazing the trail for other female biathletes.

Nebraska: The shot put-throwing football star

This might not be a name you associate with the Olympics first, especially if you know the history of football in the U.S. Nebraska native Sam Francis is in the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame for his time with the Philadelphia Eagles, Chicago Bears, Pittsburgh Steelers, and the Brooklyn Dodgers, but he was also an Olympian who came so very close to walking away with a medal. In a contest that was so close the taste of victory would have been right there, he missed a medal by just half an inch in the 1936 Olympic shot put.

KLIN says that he was already a Heisman Trophy winner, and his contributions to college athletics as a Cornhusker would see his number — 38 — officially retired.

Francis — who was also a World War II veteran — passed away in 2002, leaving his grandson to accept his induction into the Nebraska Athletic Hall of Fame on his behalf.

Nevada: The state's up-and-coming swimming star

Krysta Palmer's first Olympics was the delayed Tokyo 2020 Games, but the diver made such a splash that she was already a fan favorite in her home state of Nevada.

Team USA says that incredibly, she didn't even start diving until she was 20, and a combination of hard work, dedication, and natural talent saw her qualifying for the Olympics for the first time just nine years later. Diving wasn't her first choice, and after suffering severe injuries while training in gymnastics (that resulted in major surgery when she was just 12 years old), she refocused her energy — and abilities — into diving.

The skills she'd learned as a gymnast translated impressively well, and her new athletic career was off to an impressive start. Her attitude toward the switch? She's called it one of the hardest things she's had to do, but adds, "I've had to learn to continue the fight."

New Hampshire: Ups and downs on and off the slope

Then iconic alpine skier Bode Miller has represented Team USA at five Olympic Games — 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014 — and walked away with one gold, three silver, and two bronze. That is impressive all on its own, but it wasn't always easy. After failing to live up to the hype pushed on him in 2006 for the Turin Games, there was heartbreak for him before the 2014 Games.

That's when the 36-year-old Miller became the oldest alpine skier to take home a medal, says The Guardian, and he did it for his brother, Chelone. In 2013, the up-and-coming snowboarder died after suffering from a seizure, and took the grief with him to the slopes.

It would be his last medal. Miller retired soon after, and CBS says he shifted his priorities to his family, his promotional agreements, and his charity work.

New Jersey: Setting the bar for success early

Mel Sheppard was born in Deptford Township, New Jersey, and headed to the Olympics in 1908. It was there that he became one of the most successful athletes of the games, taking home four gold medals and one silver, all in track and field events (via Team USA).

Three of those gold medals also came with world records, and it was pretty clear Sheppard had gone a long way. The Philadelphia Inquirer says he'd been working in a glass factory since he was nine years old, and grew up as a member of the South Philly gang Grays Ferry Roaders. It wasn't until he was 17 that he became a member of an athletic club, showed the coaches how good he was, and then qualified for the Olympics. After giving President Theodore Roosevelt one of his medals, working on World War I military bases, and coaching other U.S. Olympic track teams, Sheppard died in 1942 at just 59 years old.

New Mexico: Steeplechase star

New Mexico's George Young had every intention of turning his back on sports and heading off to the Army when his University of Arizona coach introduced him to the 3,000-meter steeplechase — and then it was quite literally off to the races. Young ended up competing in four Olympics — 1960, 1964, 1968, and 1972 — and while he only took the bronze in '68, he became the first American runner to qualify for and compete in four consecutive Games.

That's made even more impressive by the fact that he trained for the event on an improvised course with hay bales doubling for the actual obstacles, and was so good that when it came time for him to head into the Army — and, inevitably, deployment in the Korean War, the Army told him that he would better serve his country on the Olympic track. After his retirement, Young set his sights on coaching the next generation of runners.

New York: From the track to the screen

Official Olympic records still credit the 1972 gold medal in the decathlon to William Bruce Jenner, but also acknowledges that she has since officially announced she is transgender, and is now known as Caitlyn.

Jenner's high-profile life as a television star tends to overshadow past Olympic achievements. After dropping out of football due to a severe injury, Jenner turned to the decathlon in college. After going to the 1972 Olympics and placing tenth, redoubled efforts sent Jenner back in 1976. That's when the world records and the gold medal came, and shortly afterwards, retirement.

Jenner later explained (via USOPM): "I have never run since the last day of the Games. I knew going in that it would be the last time I would compete. On July 30, 1976, it would all be over — win, lose, or draw ... I beat the rest of the world, sang my greatest song, and will never sing again."

North Carolina: The Golden Boy

If there's a moment when an athlete knows they've made it, it just might be the moment the Olympics refers to you as "The golden boy." That's what they called North Carolina swimmer Don Schollander, who was breaking records through the Santa Clara Swim Club long before he headed to the Olympics. When he did, it was in 1964 at Tokyo — and he'd already broken records for the 200-meter and 400-meter freestyle events. It's not entirely surprising, then, that he became the first American swimmer to walk away from the Olympics with four gold medals.

He followed that up with a few more gold medals in 1968, and then announced his retirement.

And then? According to Swimming World, he was largely forgotten until the Olympics returned to Tokyo, and there was renewed interest in the record-setting athletes that had paved the way... and lined it with American gold medals.

North Dakota: Twin ice hockey legends

In 2018, the U.S. women's hockey team took home the gold for the first time in 20 years. Front and center were North Dakota twin sisters Jocelyne and Monique Lamoureux, and they were more than front and center — it was Monique who tied the game, and Jocelyne who won it.

According to Twin Cities, the sisters decided to retire after their Olympic wins, already some of the state's most decorated Olympians with a total of six medals between the pair. It was a long road from watching the last gold medal-winning women's hockey team in 1998 to spending about half their lives concentrating on their training to become the next gold medalists, the twins said they'd done what they had come to do — and more. To say they're hometown heroes is an understatement: Until their wins, North Dakota was one of three states to never have produced a medal-winning athlete.

Ohio: The GOAT of women's gymnastics

USA Gymnastics lists Simone Biles as the "most decorated U.S. Women's gymnast ever with 31 World/Olympic medals," and that's just the start of her super-long list of accolades. It was a long, hard road to get there, though, and when she headed to the Tokyo Olympics, she did it without the most important people in her life: her grandparents/adoptive parents.

Biles hasn't just been making waves in gymnastics, she's been open about every part of the life of an Olympic athlete. She's spoken about the sexual abuse that went on behind the scenes of the USA's gymnastics team, about the neglect and hunger that shaped her childhood, and her subsequent experience with the foster care system (via Sky Sports). Discovering gymnastics when she was six years old changed her life, she's said, but still — she's made it clear that it's not an easy one.

Oklahoma: The original champion

When Jim Thorpe was born in 1888, Oklahoma was technically Indian Territory (via Britannica). He remains one of the most widely accomplished Olympians not just in the state, but in the country... even if it's not officially recognized.

Thorpe's training was done in the wilderness as he — at just 6 years old — headed out with his father to track deer and game for upwards of 30 miles at a time, and when he headed to the Olympics, it wasn't for the sport. According to the Smithsonian, he did it to prove that he was a worthy match for the love of his life, Iva Miller. (And it worked.)

Thorpe completely owned the 5-event pentathlon, and then did the same in the decathlon. Some of his records wouldn't be beaten for decades, but he was ultimately stripped of his medals when it was discovered he had played a few games of minor league baseball. They're still not an official part of Olympic record books.

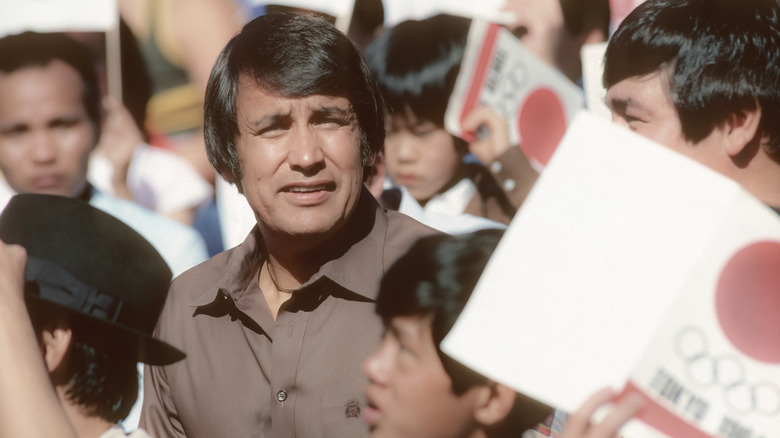

Oregon: Revolutionizing the entire sport

Oregon native Dick Fosbury headed to the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and captured the gold when he set a world record for the high jump. His 7-foot, 4.25-inch jump didn't just set a record, History says that it also revolutionized the entire sport.

Why? Because Fosbury was actually really, really bad at the high jump when he jumped in any of the traditional methods. It was only when he decided to give it a try and go over backwards that he found out he wasn't just good at it, he was record-setting good.

His weird jumping method was met with some serious ridicule at first, but when something gets results, there's really only so many disparaging things people can say about it. The so-called Fosbury Flop is now a standard in the sport, and it turns out that there's some serious science behind why it works so well, in spite of looking so weird.

Pennsylvania: Setting long jump records

Carl Lewis was one of the biggest names in track and field, and Mike Powell was the guy that beat him.

Powell competed in three Olympics — 1988, 1992, and 1996 — and while Lewis pushed him into second place in the first two, it was at the 1991 World Championships that Powell jumped a shocking 29 feet, 4.5 inches to not only take the gold, but to break the record that had stood for nearly 30 years.

The Philadelphia native retired not long after, but according to Finisher, it was 2013 that he set his sights on setting another World Masters record. Unfortunately, while there's no controversy around Powell, ESPN notes that doping scandals had tarnished the entire era of track and field. Suggestions that records from the era be wiped clean were met with outrage from Powell: "I'm serious, this is my life. I'm not going to let you do that. I'm a strong man. I stand for what I have done."

Rhode Island: Blazing a trail for women

When Aileen Riggin left Rhode Island and headed to the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, the 14-year-old diver didn't just need a chaperone, she needed to be her own very vocal proponent. She would later write (via Team USA): "It was not considered healthy for girls to overexert themselves, or to swim as far as a mile. People thought it was a great mistake."

Riggin would earn a gold in the springboard in 1920, and in 1924, a silver in springboard and a bronze in the backstroke. More important than the medals, though, was what she and her teammates did for women in sports: Yes, there was a place for women at the Olympics.

Riggin went on to become one of the very first female sportswriters when she started writing for the New York Evening Post. She continued swimming, and when she died in 2002, she held a world record for the 50-meter freestyle in the 90-94 age group.

South Carolina: A boxing great

A person doesn't know what they're capable of until they're called on to step up, and that's what happened to Joe Frazier at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Originally losing a place on the Olympic team to Buster Mathis, Frazier was taken to Tokyo as a backup. When Mathis got hurt in training, Frazier stepped in the ring, and eventually vanquished the German Hans Huber to take the boxing gold.

As if that isn't a great enough story, he also did it with a broken thumb that he just sort of didn't bother to get treated... not, until he won.

What happened afterwards is a sporting legend, and Frazier went on to become one of the sport's legendary figures. But what happened to Frazier's medal? In 2004, he revealed: "I had my Olympic gold medal cut up into 11 pieces. Gave all 11 of my kids a piece."

South Dakota: Proving them all wrong

Billy Mills grew up on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, and later recalled a life of playing outside and eating what local gardens supplied for dinner. He was also orphaned as a young boy, and faced shocking racial discrimination when he decided to play sports. To show all his detractors what he could do, he promised himself that he was going to win an Olympic gold — and he did.

When the U.S. Marine lieutenant headed to the 1964 Tokyo games, he was up against some record-setting runners in the 10,000-meter. When he won, he later said, "...there were two races. The first was to heal the broken soul. And in the process, I won an Olympic gold medal."

The USOPM says that Mills has gone on to found an organization for Native American athletes, and in 2012, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Citizens Medal.

Tennessee: From leg braces to world records

When Wilma Rudolph was just a toddler, her parents were told that she would never walk again. Born in Saint Bethlehem, Tennessee in 1940, Rudolph suffered from both polio and scarlet fever, and relied on a leg brace. She not only walked: she went on to become one of the fastest women in the world.

Her parents never gave up on her, and by the time she was six, she could hop about on her own. She was walking at eight, playing basketball at 11, and in 1956 — at 16 years old — she headed to the Olympics and took the bronze in the 4x100 relay. That was followed by a trip to the Olympics in Rome, three gold medals, and three world records.

The National Women's History Museum says that Rudolph used her fame to not only push for integration and bring sports to the next generation. She died in 1994, and still has buildings at Tennessee State University named after her.

Texas: Taking a stand

Even those that don't know the names know the photo: Two medal-winning American Olympians, standing on the podium, black-gloved fists raised. Texan Tommie Smith was at the Mexico City podium to accept his gold medal for the 200-meter dash.

It marked one of the most controversial moments seen at the Olympics to date, and while the gesture was met with a solid cry of protest and booing from the crowds, Texas Monthly says it marked the start of athlete activism. Thanks to Smith — and teammate John Carlos from New York — athletes suddenly realized that no, they didn't have to keep quiet.

When asked what had been going through his mind as he stood on the podium, he said, "Sadness. ... As I put my hand up in the hair, I saw negative creatures. That's all I saw. Negativity in the air. ... When I took my hand down, I said to myself: 'Okay, Tommie, close the chapter and start another one.'"

Utah: The youngest to ever win a medal

There's nothing quite like the achievements of Olympic athletes to make the average person watching from their couch feel like a slacker, and that goes double for Dorothy Poynton-Hill (right). Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, she qualified for the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam when she was just 12 years old. What were you doing at 12? Not making your middle school soccer team? Technically, the young diver turned 13 while en route to the games, and when she won the silver medal at the springboard diving competition, she became the youngest medal-winning Olympian — a record that still stands today.

She headed to the games again in 1932 and in 1936, won medals in both, and according to Utah Women's History, by the time she retired, she had won every possible title and honor at least one time. She passed away in 1995.

Vermont: America's favorite snowboarding sensation

NBC Boston called snowboarder Kelly Clark an "Athlete to Watch," and said that for those back in her hometown of West Dover, Vermont, that's exactly what they were doing.

Clark had her Olympic debut in 2002, when she took a gold medal back home with her. That was followed by a bronze in 2010 and another bronze in 2014, and Clark had nothing but glowing praise for her home state — where she grew up hoping for snow days so she could head out onto the mountains. "I think that just kind of speaks to the culture of Vermont," she explained. "There's a small-town feel, but big achievement."

Her former teachers have called her the "grande dame" of snowboarding, and when she announced her retirement in 2019 (via ESPN), she acknowledged it hadn't come easy, saying: "sometimes you value things based on what they cost you."

Virginia: A controversial boxing champ

The U.S. boxing team of the 1984 Olympics was deep with talent considering it included names like Evander Holyfield, and it was led by Virginia native Pernell Whitaker. The gold medalist was born in Norfolk, and after the Olympics went on to become an IBF lightweight champion.

But unfortunately, his Olympic success would be the high point of his life. According to The Guardian, his later career was filled with the scandal of alcohol and drug abuse, along with financial problems as the money he had made in the ring dwindled. And there were a lot of fights — by the time he retired, he had a record of 40 professional bouts with just four losses and one draw.

In 2019, he tragically died at the age of 55. Pernell was crossing the street in Virginia Beach when he was struck by a car and killed.

Washington: Love what you do

The sports of the Winter Olympics in particular are the ones that make viewers hold their collective breath, and in 2002, 2006, and 2010, Washington's Apolo Ohno was the one to watch, if your eye was fast enough. He walked away from those three Games as Team USA's most decorated Winter Olympian, with two gold medals, two silver, and four bronze in short track speedskating.

Ohno was so popular that Forbes says his skates were displayed at the Smithsonian, and adds that part of the reason why everyone loved him is that it was clear he really loved what he was doing. He retired at 28, became a professional speaker and author, appeared on — and won — "Dancing with the Stars," and says his most meaningful medal is his first silver. He took that after being knocked down just before the finish line, and still managed to grab a silver.

West Virginia: The gymnast to watch

Mary Lou Retton made history in 1984, when the West Virginia State Museum says she became the first American and non-Eastern European gymnast to take home the gold. And it wasn't just "the" or "a" gold, it was five of them. She followed that up with two silvers and two bronze medals, and she was just 16 years old at the time.

The Fairmont, West Virginia native went on to compete at just one more high-profile competition — the American Cup — which she also won. She announced her retirement shortly afterwards, and by September of 1986, she was done. She explained (via NBC Sports): "I was ready. I knew that I was not going to be one of those athletes that's just hanging on to the sport and couldn't retire, couldn't let it go. I wanted people to remember me as a winner and a champion and not some struggling older athlete that just can't let it go. That was important to me."

Wisconsin: From skating to cycling

The Madison, Wisconsin-born Connie Carpenter-Phinney went to her first Olympics when she was just 14: It was 1972, and she was competing with Team USA as a speedskater. It was then that her story took a bit of a turn, and when an injury derailed her skating career, she turned to cycling.

That all happened in 1976, and she bounced back to start taking national titles in road cycling that very same year. It was cycling that would get her a gold medal in 1984, and inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame. She was the first female athlete to take that gold, and according to Cycling Tips, her entire career was inspired by her mother. "My mother suffered from MS. It's a debilitating illness. I think I moved a lot partially because she couldn't, but it's also very much a part of who I am."

Wyoming: America's favorite Greco-Roman wrestler

Rulon Gardner's sport of choice was one of the most ancient: Greco-Roman wrestling. His 2000 victory over a three-time Olympic champ was one of the biggest upsets of the Games, but his life outside of stardom hasn't been an easy one.

From growing up with a learning disability to being ridiculed for his weight, to suffering through several accidents that left him near death, to his continued struggle with his weight and bankruptcy, Gardner has had his share of ups and downs. Some of it was very public: He was a contestant on the weight loss reality show "The Biggest Loser," and ended up leaving early for personal reasons.

Through it all, though, he's kept going — and at the time the movie based on his life was released, he was working as an insurance salesman, speaker, and wrestling coach. He says: "All I can do is use the experiences of my life to inject knowledge into our youth. Hopefully, they can see that."