What Mermaids Look Like In Different Cultures

Danish author Hans Christian Anderson arguably wrote the first definitive mermaid fairytale. Anderson's fairy tale is dark, with a tragic ending, and has a very specific religious element to it, as his mermaid must labor to achieve her soul and therefore be able to enter Heaven. Meanwhile, the Disney movie that used his book as inspiration was colorful with singing marine life and a happily ever after. Plus, the mermaids were the stereotypical beautiful women crossed with fish, and so that's what most people these days picture when they think of mermaids.

And sure, according to Britannica, in traditional tales, mermaids (and mermaid-like creatures) often marry men, although said marriages usually come with conditions that must be fulfilled. (Otherwise, the mermaid will leave for the sea.) However, there is much more than that in mermaid legends and myths around the world. Water spirits and fish-human hybrid creatures exist in several cultures' mythology. For example, the Greeks have nereids, while the Japanese have the kappa. These creatures vary in terms of their beauty and their helpful or hindering nature towards humans. Though each mermaid-like creature has a slightly different appearance and aspect it's known for, overall each creature is a water-lover in one way or another. Fish scales appear again and again across mythologies. Promises and keeping the sea a secret are also recurring elements for mermaids around the world.

So, what other types of mermaid-like watery creatures exist in the world? Here's what mermaids look like in different cultures.

Japan: Kappa

The kappa is a vampire-like, lustful, scaled creature in Japanese mythology. They are yellow-green in color, are covered in fish scales or tortoise shells, and yet — somehow — are apparently similar to monkeys, at least according to Britannica. Perhaps unsurprisingly, their stories do not involve rhapsodies of their beauty or the idea of marriages to humans.

Also, the shape of their heads makes a little bowl at the top, which they keep filled with water. That part is pretty vital, because if the water is spilled, kappas supposedly lose their powers. References to kappa also include their ability to keep promises, and humans often manipulate kappa into keeping said promises by spilling their water, either by forcing them to bow or otherwise pressing their heads down.

They are less hostile towards men than the demonic omi, also from Japanese myth, but are smarter. Kappa, according to the mythology, taught men the infinitely useful art of bonesetting, which you'll appreciate if you've even broken or dislocated a bone. On the other hand, they are said to be fond of cucumbers, so if you aren't up for a osteopathy lesson, an encounter with a kappa can be avoided by throwing a cucumber into the water where they live.

India: Naga

Nagas are half-cobra and half-human partly divine beings found in Hindu mythology, Jainism, and Buddhism. According to Britannica, they can either turn wholly human or wholly serpent. Specific naga are known in Hindu mythology, such as Shesha (also known as Ananta) who holds up Vishnu on the cosmic ocean in the creation myth.

But Brahma, the creator god, banished the nagas to their own realm, which is called either Naga-loka or Patala-loka, when they began to get too populous on Earth. Their netherworld is filled with beautiful palaces and gems. At the time of their banishment, Brahma commanded them to only bite those who will die prematurely, or those who are truly evil.

Nagas are primarily associated with bodies of water, such as wells, lakes, rivers, and seas, and spend their time guarding treasure. They can be dangerous but mainly help humans, like how they make sure humanity gets enough rain (although sometimes they hold onto it too long), writes Myth Encyclopedia. Female nagas are supposedly very beautiful and the ruling families of Manipur and Funan, as well as the Pallava dynasty, all claimed descent from a naga.

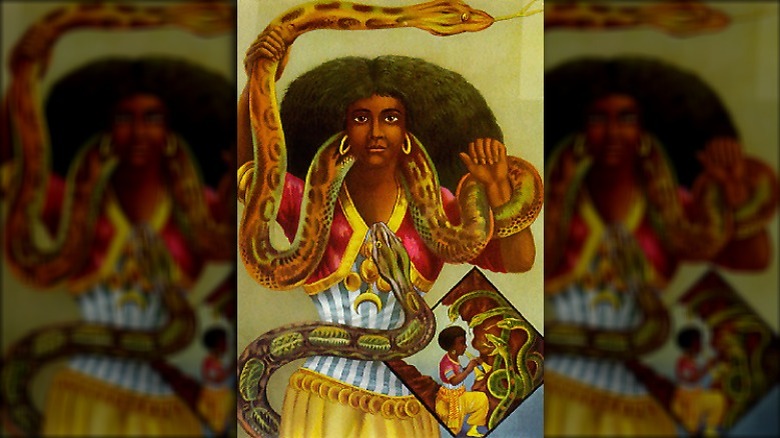

Africa: Mami Wata

Mami Wata (Mother Water) is a water spirit celebrated across Africa. She is often depicted as either a mermaid, snake charmer, or a combination of the two. She is revered as the sacred, life-giving nature of water, writes the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. Mami Wata can also be referred to in the plural, as she makes up several mami and papi watas who comprise the vast collection of African water spirits.

Mami Wata can bring good fortune by way of money; this aspect probably developed between the 15th and 20th centuries due to the growth of slavery and trade throughout the world.

Due to enslaved Africans being taken from their homeland and brought elsewhere, the belief in Mami Wata similarly spread through different parts of the world. Her depictions have been influenced by several cultures on different continents, including Hindu gods, European mermaids, and saints from Christianity. Slavery and trade dispersing the African people across the globe influenced how they believed – and the nature of what they believed in. Today, she is worshipped in Brazil, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic, as well as Africa.

Cameroon: Jengu

The jengu (miengu in plural) is a mermaid-like creature with long hair and a gap-toothed smile that live in rivers, according to the beliefs of the Sawa ethnic groups of Cameroon. Miengu act as the go-betweens for spirits and humans, bring good fortune, and serve as healers, per The Illustrationist. The creatures also bring crayfish and success in canoe races, writes the Bestiarium.

For young girls of the Bakweri tribe, jengu-worship is a rite of passage. The girl must wear a fern frond dress and observe a number of taboos before being declared an adult.

Another ritual is observed in Douala, where the Ngondo festival (pictured) takes place. During the festivities a diver enters the water with a calabash (a type of gourd). After several minutes, the diver returns. While he is gone, he is meant to be visiting the underwater kingdom of the jengu. The markings on the returned and miraculously dry calabash are meant to be messages from the gods.

Germany: Lorelei

The Lorelei (or Loreley) legend was essentially created by German writer Clemens Brentano for the poem "Zu Bacharach am Rheine," which appeared in his 1801 novel "Godwi." Lorelei's tale was later used for several other pieces of literature and songs. The basic story is about a German woman who flings herself into the Rhine River after her lover cheated on her. There she is turned into a siren, the type of creatures who enchant men with their beautiful voices and lead sailors and fishermen to their own destruction, writes Britannica.

There is a large rock associated with Lorelei on the bank of the Rhine in Germany, visible from a passing train or ship on the rive. This part of the Rhine is known for being steep and narrow, and several ships have crashed there, writes Real Travel Experts. Not convinced it's Lorelei the siren's doing? Well, the rock was known for producing an echo, at least before the advent of industry and its loud noises. In fact, the word "lorelei" means "murmur of rocks" according to the Celtic and German words it is most likely derived from.

There is also a statue of Lorelei that one can walk to from the nearby town of St. Goarhausen.

Europe: Melusine

Melusine is the daughter of a fairy who, after locking her father in a mountain, is condemned to half-transform into a serpent once every week. But when a poor French noble falls in love with her, she agrees to marry him, on one condition: He cannot look at on her on Saturdays. This is when, unbeknownst to him, Melusine does her transforming in private.

During their marriage, his land prospers (possibly giving rise to the benevolent fairy godmother archetype). But, of course, the lord does eventually grow too curious, and sneaks a Saturday peek on his wife, seeing her weird snake tail. So Melusine transforms into a dragon and flies away, although she supposedly keeps tabs on her sons, returning occasionally to cry near their home. Melusine's story shows once again the importance and impact of keeping promises made to mermaids.

Melusine's story emerged in the 14th and 15th centuries, drawing upon Celtic mythology, writes the British Library's European Studies blog. Several European families claimed to be descended from her, including Jacquetta of Luxembourg, whose daughter was Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England.

Solomon Islands: Adaro

The Adaro are water spirits in the beliefs of the Solomon Islands. They possess gills and fins, but otherwise resemble humans ... oh, right, except for the dolphin-like fin on their back. So you can see they take on much more of the disparate fish body parts, as opposed to the very simple – not to mention attractive – fish tail that European mermaids have. In fact, there is no "maid" about it, as Adaro are universally male, and are described as mermen. They supposedly live in the sun, but travel back and forth to Earth by use of rainbows and waterways like rain showers and water spouts.

In addition to the gills and fins, the Adaro also have spears growing out of their heads, which probably come in handy for them considering they are very hostile towards humans. Adaro visit people in their dreams to teach them music and dances, but would otherwise kill humans on sight with poisonous flying fish. According to Mythical Beast Wars, they are thought to represent the negative part of the spirits of the dead, and therefore might form immediately after someone dies.

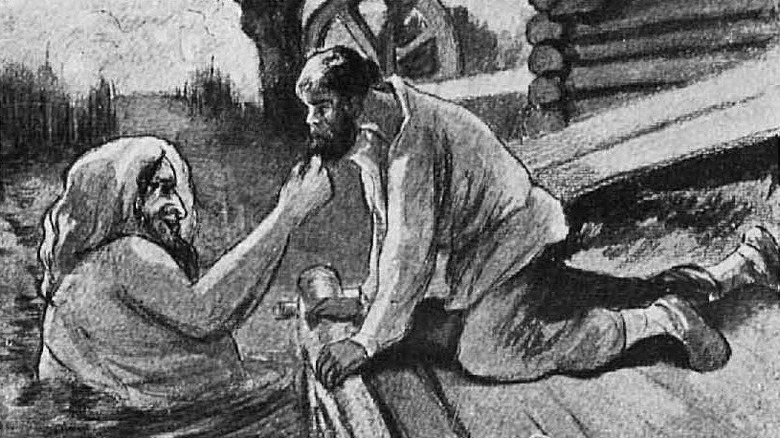

Slavs: Vodyanoi

The vodyanoi is a large green protective water deity in Slavic mythology who prevents rivers and swamps from becoming contaminated. He is malicious to humans, probably fearful of their lack of intense conservationist tendencies, and will drag someone into the river if given the chance, according to legend. When men drown in rivers, they become vodyanoi, writes God Checker. Vodyanoi haven't become accustomed to their lot in life, and therefore drowning people out of anger.

However, they respond well to polite behaviors such as saying hello and doffing hats. Offering vodyanoi fish or butter are also ways to stay on their good side. Evidently human food is a novelty for water spirits. It's also possible that the vodyanoi are simply craving the food they had in their previous lives, and will therefore pardon those humans who bring it.

The vodyanoi has also become well-known through Slavic and Czech folklore and literature. They have also appeared in various games such as "Dungeons and Dragons" and the video game adaptation of "The Witcher."

Greece: Nereids

The nereids are a group of sea nymphs from Greek mythology. Specifically, they are the 50 sea nymph daughters of Nereus, a sea god who was the son of Pontus (the personification of the sea) and Gaea (the personification of the earth). Their name, "nereid" means "daughters of Nereus" and also "the wet ones," which is fitting for a group of sea nymphs. The nereids lived with Nereus in a grotto at the bottom of the Aegean Ocean.

One nereid, Amphitrite, was the sea god Poseidon's queen, while another, Thetis, was the Greek hero Achilles' mother. Thetis, while not as powerful as a goddess, was able to call in many favors from other gods in her eventually-fruitless attempt to save her son from the Trojan War.

The nereids protected those who needed help on the ocean, such as fishermen, but were also nymphs of bounty. They represent individual facets of the sea, as well as fishing skills, writes Theoi. In art, they are often depicted as beautiful young women.

Slavs: Rusalka

According to Ancient Origins, Rusalki are similar to the Greek sirens: beautiful women who entice men. They are often pale with long hair, don't have pupils, and their eyes can turn green in times of wickedness. While they often live in bodies of water, such as lakes, rivers, ponds, marshes, and swamps, they do have legs, and therefore can move around on land. Rusalki are also said to only live in the water for a specific amount of time.

Rusalki mainly avoid humans, but focus on giving water to the fields and forests as they dance in the spring season. They were therefore treated respectfully since they brought the water that helped crops grow. In Slavic pagan folklore, they are symbols of fertility. During the beginning of summer, Slavic cultures used to celebrate the rusalki for a week. Rusalki are believed to come ashore and swing in the trees and dance during this time. In bountiful areas, they have a playful nature, while in stark places, they can turn evil.

In later centuries, that evil side became more prevalent, as Rusalki began to be thought of as malevolent to humans. In the ballet "Giselle," the wilis are creatures who dance men to death at night, and have similarities to versions of the Rusalki myth. Rusalki came about by way of the violent death of a young woman, most commonly drowning. Other myths say they are made when anyone drowns. During the annual Rusalki festival, swimming was forbidden, since it would prove deadly.

Celtic and Norse: Selkies

Generally regarded as gentle creatures, selkies are seals who can become human, and were supposedly very common in the Orkney Isles. The word "selkie" even means seal, in Orcadian dialect. Even though selkies do not have any fish traits as mermaids do, they are inherently of the sea.

According to surviving folklore, it's not clear how often a selkie could transform, whether it was once a year, every ninth night, or another unspecified time frame. When human, they often dance on the shore or sunbathe on the rocks. According to Orkney Jar, the most important aspect of the selkie myth is their sealskin, which they needed to transform. If the sealskin was stolen or somehow lost while in their human form, the selkie would be unable to return to the sea since they could not transform back into a seal.

Male selkies would often transform into human men and go out to seek unmarried (and sometimes even married) women, who found the selkies attractive. Occasionally, when a woman would go missing, it might be thought that her selkie lover had taken her to live with him in the sea. Selkie women, on the other hand, were often tricked into giving up their sealskins by human men in order to marry them and have their children. Usually, the sealskin would be found by the selkie's children, and in some stories they would follow their mother into the sea, while in others they would stay with their father on land. Even if the selkie's children had the ability to become seals themselves, this was undoubtedly a difficult choice to make.

Australia: Muldjewangk

The muldjewangk is a large, half-human, half-fish creature from Australian Aboriginal mythology who is able to wreak havoc on ships. According to Astonishing Legends, it is unclear whether there is only one muldjewangk, or whether there are several. Generally in these tales it appears alone, without family. It is considered both a merman and a monster, depending on the story. It inhabits water, and particularly likes the Murray River and Lake Alexandria in Southern Australia. Large pieces of seaweed supposedly act as hiding spots for muldjewangk, writes Haunted Auckland.

The muldjewangk is an effective bedtime story for children to get them to avoid the water or looking too far off the side of a boat. A standard tale has the muldjewangk pestering Ngurunderi (a sort of creation god of the Ngarrindjeri people) and his wives when they landed on Lake Alexandria, destroying their fishing nets so they have no yummy fish to eat. But one specific story told about the muldjewangk features it possessing other, lesser-known, and more concerning powers. A ship carrying European passengers and some Aboriginal elders is on the Murray River when a muldjewangk starts to tear into the boat with its hands. The captain tries to shoot it, despite the elders begging him to stop. Eventually, the muldjewangk slinks back into the river. Days later, the captain comes down with a terrible disease that he dies from six months later. It is the muldjewangk's revenge.