Here's What It Was Like For Prisoners In Ancient China

Before the upheavals of the 19th and 20th centuries, China had an ancient and glorious history. As explained by the World History Encyclopedia, China is the world's oldest extant civilization today. Part of China's long-term success has been its effort to harmonize its society at any cost, which raises the topic of law and punishment.

Popular imagination has lingered on the terrible fate of prisoners in ancient and Imperial China. This is mainly due to the exotic torture techniques. Think for example of the bamboo torture, in which a prisoner is restrained over a bamboo seed. Then, over the course of days, the bamboo shoot grows and slowly impales the prisoner. Another is the famous water torture, which had several fiendish variations from dripping water on a person's head or submerging the head in water. The treatment of prisoners in ancient and later Imperial China was meant not so much to provide justice, but rather to remove any sort of dissent within society. So let's look at the grim reality of being a prisoner in ancient China.

Prisoners in China were treated pretty much the same way over the course of millennia

If this is an article about ancient China, why are we talking about Imperial China as well? As strange as it may sound, a prisoner in Imperial China's criminal justice system in the early 20th century was subject to the same ideals and principles as a convicted criminal of ancient China in the 2nd century BC. "The Confucianization of Law and the Lenient Punishments in China" notes that from the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) to the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644 to 1911), China's penal code and its philosophical underpinnings were consistent.

While there was some evolution over the centuries, the changes had more to do with the historical details of the time period rather than wholesale changes in attitudes as to who should be imprisoned and why. Therefore, the same categories of punishments were applied to people who lived centuries apart. This was because the law was founded on philosophical principles that endured in Chinese civilization until the 20th century.

The criminal justice system was influenced by Confucianism and Legalism

According to Britannica, the first Imperial law codes of a centralized Chinese state came about when the Shihuangdi established autocratic rule as the first emperor of the Qin dynasty in 221 BC. How autocratic was Qin rule? The World History Encyclopedia describes book burnings and executions of uncounted men, women, and children who did not obey the law.

Qin China was ruled by a philosophy known as Legalism. This school of thought believed that humans were naturally bad. The logic went that to create a harmonious society where the weak were protected, the laws needed to be simple, brutal, and effective. The founder of Legalism, Han Feizi, wrote, "The ruler alone should possess the power, wielding it like lightning or like thunder." Laws were draconian, and convicted prisoners were subject to torture, enforced labor, or execution. Mainly, execution was performed by beheading, but sometimes chariots would tear a prisoner's body apart or they would be boiled in a cauldron, and prisoners were presumed guilty unless proven innocent.

With a law code like that it is no wonder the Qin dynasty was overthrown by the Han dynasty in 206 BC. The Han dynasty remade the penal code to embrace the principles of Confucianism, but it was still highly influenced by the tenets of Legalism.

The worst crime in ancient China was to disobey your parents

Ancient China's penal law emphasized filial piety in five primary relationships: how people should behave toward their rulers, parents, spouses, siblings, and friends. This had consequences for prisoners, since people who committed the same type of crime would be treated differently depending on if they did it to a person who was their junior or senior or who were their husband or father. For example, a prisoner in ancient China who committed a crime against an older person would be subjected to a worse punishment than if they did the same crime to a younger person. To show how serious filial piety was, if a child turned in a parent for a crime, unless it was for treason or rebellion, the child was punished with the parent for breaking filial piety.

This penal law carried throughout Imperial China's history. An example of how prisoners were treated differently is provided by "The Death Penalty in Traditional China." In 1831, a woman called "Mrs. Han" accidentally injured her father-in-law which resulted in his eventual death. Such a crime required execution by slicing (more on that later). However, in an act of compassion, the emperor reduced the sentence to the more merciful death by decapitation. What is more, while awaiting sentencing Mrs. Han gave birth to a child. By law, she was allowed to care for her child for 100 days before she was beheaded.

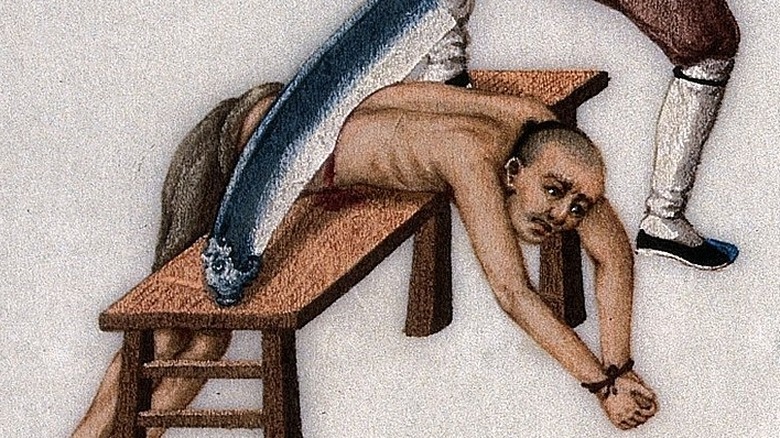

Torture was used regularly against prisoners in ancient China

An important legal principle in ancient and imperial China was that in order for a prisoner to be convicted of a crime, he or she must confess that crime. If you were an accused prisoner, at first blush this may sound promising. Perhaps you wouldn't confess that you stole your neighbor's chickens and get off scot-free.

Think again. As the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies explains, in order to obtain a confession, it was perfectly fine for the authorities to use torture. Before the torture started, though, a captured offender could voluntarily confess that they did the crime. If so, then it was built into the legal code that the punishment was to be reduced.

This loophole became fully developed by the Qing Dynasty whose laws stipulated that if you confessed a crime before it was found out, you were not to be punished, albeit you'd be responsible for any losses. Furthermore, if you confessed to a crime and then it was subsequently discovered you were guilty of a lesser crime, you were not held responsible for the lesser crime since you were being punished for the greater ones. Lawbreakers could even send somebody to the authorities to confess for them. There were exceptions for this type of leniency, particularly in cases of murder, physical injury, or such property damage that no restitution was possible. But many prisoners did not confess so judges would order torture.

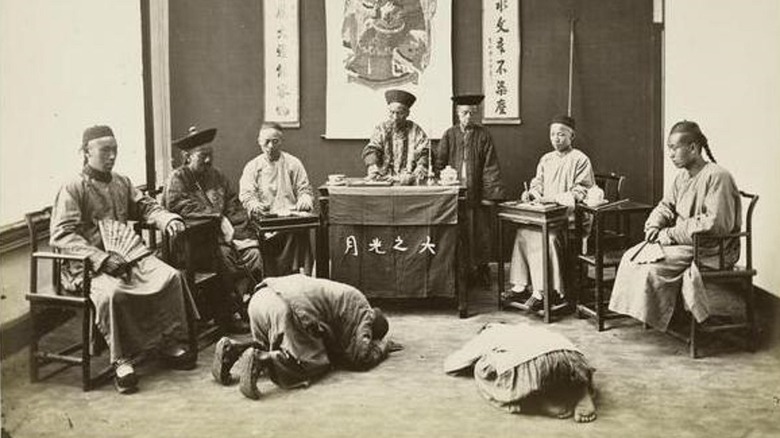

Ancient China tortured prisoners and witnesses to get confessions

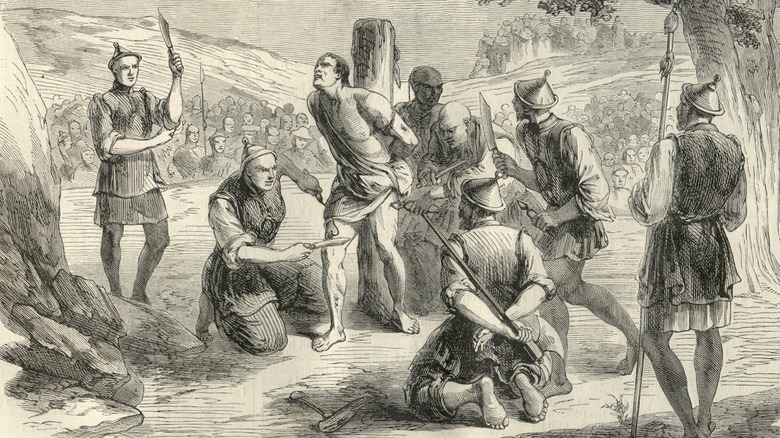

In ancient China, the whole investigative and judicial process was strict. Witnesses and accused would prostrate themselves before an official through the entire proceeding. Duhaime reports that the accused would be asked leading questions. If the prisoners started evading questions, the authorities pressed the torture button immediately. At this stage, the form of torture is very simple and direct. A prisoner or uncooperative witness's arms were twisted about a pole. They were then beaten continually as long as they proclaimed innocence.

"Reform and Development of Powers and Functions of China's Criminal Proceedings" explains that even though from time to time there would be a wrongly tortured prisoner who "confessed," on the whole the torture system worked to gather evidence more rapidly, solve cases, and cut investigatory costs. Chen wrote, "In criminal cases, the interrogation which mainly aimed at obtaining the defendants' confession became the main means of judicial proof, which laid basis for the prevalence of extortion of confessions by torture." As a result, for investigators, torture was assumed to be an important part of the investigatory process.

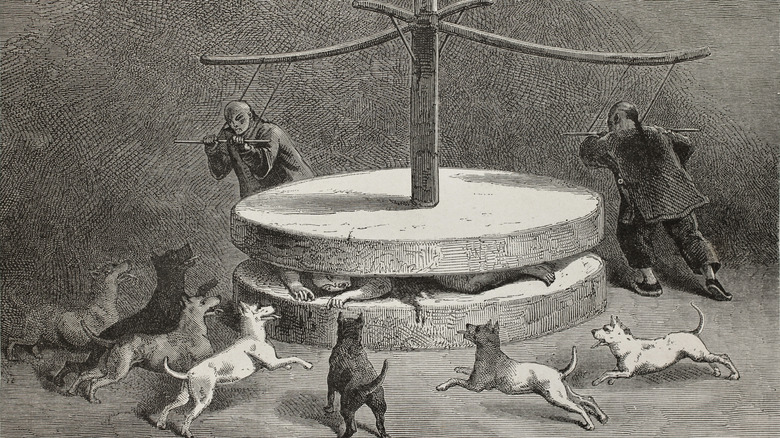

Convicted criminals in ancient China rarely actually went to prison

So let's say you were convicted of a crime in ancient China. What happened? Were prisoners expected to be reformed or were they expected to be punished? In ancient China, penal law was viewed as being the enforcer of Confucian values and morals whose purpose was to create a well-ordered society. It was considered that laws were a part of the moral framework of civilization and if you broke a law, you deserved what was coming to you.

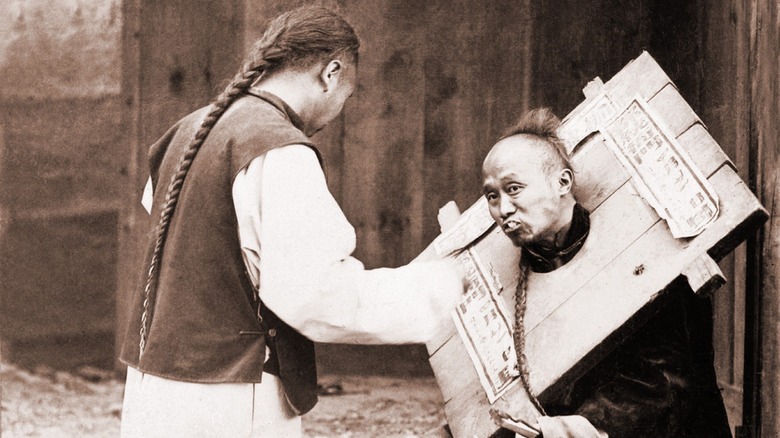

Still, "The Confucianization of Law and the Lenient Punishments in China" notes that Confucianism demanded moral action by leaders and that punitive enforcement should be a last resort. Yet punitive enforcement was always a frequent occurrence. According to "The Death Penalty in Traditional China," the penal code in Imperial China was mostly based on forms of corporal or capital punishment. While there were prisons and in certain instances convicts were in prisons, in most cases, prisoners were punished bodily for their crimes. This meant that prisoners were subject to execution or torture depending on the severity of the crime. Duhaime explains that much of the punishment was merely cruel and unusual. Public whippings or caning in front of a judge were normal punishments. Also used were cages and contraptions that locked the neck, or tied a heavy stone to the neck. Most of these types of punishments fell under one of its categories of the "Five Punishments."

Prisoners in ancient China were subjected to one of the 'Five Punishments'

As described by "The Death Penalty in Traditional China," China implemented a penal system on prisoners called the Wu hsing translated to the "Five Punishments." Which of the Five Punishments categories you got depended on your crime. Before the Qin dynasty, the five punishments were: tattooing, amputation of the nose, amputation of one or both feet, castration, and death. But the Five Punishments evolved so that by the time of Sui Dynasty (581-618 C.E.), there was beating with a light stick, beating with a heavy stick, penal servitude, exile, and death by strangulation or decapitation.

Within each punishment there were different degrees. For example, a prisoner who was sentenced to be beaten with a light stick could be sentenced to up to five degrees of punishment which dictated how many blows would be delivered (between 10 to 50). Even exile was subject to degrees so that the more severe the crime the farther the convict went afield.

As for execution, decapitation was considered worse than strangulation. This may seem strange since strangulation, in which the executioner used a rope on the throat, was exceedingly brutal and long. Meanwhile, a beheading called for only a skilled sweep of the sword. Yet, beheading was considered more disrespectful and demeaning to a body that had been bequeathed by a person's ancestors, and thus a more disgraceful way to die.

The Death by a Thousand Cuts was the worst punishment possible for a prisoner

"The Death Penalty in Traditional China" describes how the Five Punishments continued to evolve into some pretty horrific means of punishing prisoners. According to Britannica the Ling chi, known as "death by slicing" or "death by a thousand cuts" began as early as the 10th century. Ling chi was considered the worst punishment possible for any prisoner. This fate was meted to those who were guilty of only the highest crimes of the land known as the "Ten Abominations." These included treason, mutilation, patricide, murder of a husband, rebellion, and witchcraft.

The Ling chi usually consisted of eight slices to the body (though it could be more). This usually started on the face followed by the hands, feet, chest, and stomach. The final cut was to the heart or decapitation. One English observer wrote: "This punishment ... is inflicted not so much as a torture, but to destroy the future as well as the present life of the offender. He is unworthy to exist longer either as a man or recognizable spirit ... As spirits to appear must assume their previous corporeal forms he can only appear as a collection of little bits. It is not a lingering death, for it is all over in a few seconds, and the coup de grace is generally given the third cut..." Ling chi was banned in 1905.

Prisoners in ancient China were kept in dungeons

A modern prison would be like the Four Seasons when compared to an Imperial Chinese prison. In addition, China from the time of the Qin dynasty, according to "A New Study on the Judicial Administrative System with Chinese Characteristics" had built a prison system that gradually expanded through the centuries and was systematized. According to Prisons and Prison Systems, a stone tablet from 723 C.E. decreed that Buddhist temples should be built near prisons in China, presumably as part of a non-existing rehabilitation process. This did not make them, however, less horrible.

As described by "The Death Penalty in Traditional China," prisons were foremost holding centers for those who couldn't afford bail or were connected to officials. The accused would linger enchained in these dungeons awaiting trial. They would also mingle with those who had been sentenced to prison. Food was only provided by relatives and guards, as may be expected, often abused their charges. According to "The Philosophy of Civil Rights in the Context of China," all incoming prisoners were given a flogging. In fact, some prisoners, in a show of bravado and perhaps to impress his or her fellow prisoners, asked to be flogged. The expected lifespan of a prisoner in ancient China was short.

Prisoners in ancient China were never executed in the spring or summer

Prisoners in ancient China were subject to the philosophical tenets that guided people's spiritual beliefs. This meant that some of the actions around punishments were taboo. Daoist principles of natural harmony blended with Confucian ideology. The idea was that people and nature were so closely tied to one another that one should act in harmony with it.

So what did this mean for prisoners? Spring and summer were seen as periods of renewal and growth while autumn and winter were seen as the opposite. "The Death Penalty in Traditional China" details how execution, which is a way to destroy life, could only occur in the autumn or winter, according to Chinese tradition. If an execution were to happen in the wrong season, it would throw the natural order off balance. During the Han Dynasty, for example, no serious trials or judgements could be handed down after spring began. The number of taboo periods changed with the different dynasties. The Tang had the most, barring executions on rainy days, at night, and during particular phases of the moon. In addition, certain months and feasts in the Buddhist calendar also prohibited execution.

Prisoners of war in ancient China were subject to execution or enslavement

Early in Chinese history, if you were on the losing side of the battlefield and got captured you were completely at your enemy's mercy. Before the Qin dynasty, enslavement and execution seems to have been the most popular fates for prisoners of war. However, prisoners of war were also liable to suffer more.

According to the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology prisoners of war were executed as part of ritual sacrifice during that period. In fact, sometimes raids were, according to "Ancient China," purposely led in order to collect sacrificial victims. Women who were captured were often assaulted and made to become concubines of the victorious officers, as described in "Women in Imperial China." In addition, "Historical Origins of International Criminal Law" asserts that any prisoners captured in China 6,000 years ago may even have been eaten as food during periods of famine. These practices of human sacrifice and cannibalism disappeared long before Imperial China was established. The treatment of prisoners of war improved somewhat after the establishment of Imperial China.

Modern China sometimes uses the same methods against prisoners as ancient China

It has been reported through multiple newspaper sources that modern China still often treats prisoners the same way as ancient and Imperial China. In 2021, the Guardian described how Chinese citizens are often secretly seized, detained, and tortured.

Many of these allegations concerning torture in contemporary China are associated with the country's treatment of its ethnic minorities. The New York Times reported that as part of China's campaign to assimilate Tibetans, there have been many human rights abuses which include arbitrary arrest and the torture of political prisoners. In fact, Forbes detailed how the United Nations has decried allegations of forced organ harvesting among prisoners who are Falun Gong followers, Uyghurs, Tibetans, Muslims, and Christians. Aside from these allegations, prisoners in China today may be subject to physical and sexual abuse, forced labor, and forced sterilizations. The United Nations is trying to engage the Chinese government on this serious human rights issue.

It's astonishing to think of what hasn't changed for prisoners in China for thousands of years.