The Untold Truth Of Nazi Filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl

You may not know the name Leni Riefenstahl, but you've almost definitely seen her work. Picture shiny boots marching on steps, cheering crowds, Hitler yelling "Nein" a bunch of times. Her most famous film, "Triumph of the Will" — which, yes, was commissioned as a Nazi propaganda piece — has been quoted and referenced in countless movies over the years, including an extremely unsubtle sequence in "Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens."

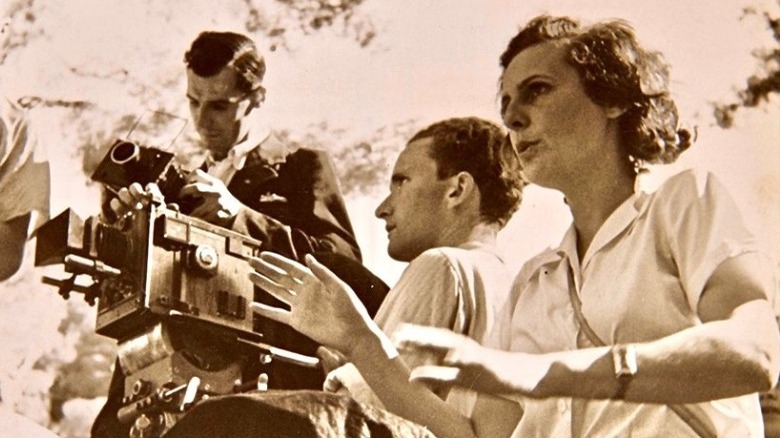

The Nazi machine was, first and foremost, a propaganda machine. They weren't great at governing, and they were garbage at winning wars, but they were experts at manipulating the media and controlling how they were perceived. The widespread support Hitler achieved in 1930s Germany owes no small part to the mountains of self-glorifying propaganda he disseminated, and at the frontlines of that propaganda battalion was filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. And she wasn't just a pretty face or a decent artist; she was a revolutionary filmmaker, creating countless cinematic techniques that are still in use today. Let's take a look at her wild life and her sometimes-ambiguous relationship with Nazism.

She only turned to film because of a knee injury

Born into a middle-class German family, Riefenstahl had a father who was hoping his daughter would follow him into the exciting world of heating and ventilation (via the University of Washington). Fortunately, or unfortunately, depending on how you want to think about it, Leni's mother encouraged her in her artistic ambitions, pushing her to paint and write poetry. Leni was also a gifted athlete, participating in both swimming and gymnastics. As tends to happen with artists who are also good athletes, Riefenstahl found her way into dance, and actually toured Europe with an interpretive dance troupe.

Her dancing career was cut short by a knee injury, however, so she turned to acting (via Military History Matters), eventually persuading director Arthur Frank to cast her in some of his "mountain films" (a popular genre in Germany at the time). Film proved fascinating enough to Riefenstahl that she took it up as her new career, eventually writing, directing and starring in the dark fairy tale "The Blue Light" (it's about a witch who lives on a mountain ... and emits blue light).

"The Blue Light" proved to be a phenomenal hit, and got scads of attention, including from a guy named Adolf Hitler (via Britannica).

She invented multiple techniques filmmakers still use today

If Adolf Hitler is known for anything, it's for being an aficionado of cinema, so he knew talent when he saw it. Based on the innovative techniques on display in "The Blue Light," he commissioned Riefenstahl to direct propaganda films for the Nazi Party. If Riefenstahl was reluctant to make art for a government widely considered to be one of the most evil in history, she didn't show it. While she was initially shy to direct "Triumph of the Will" (her magnum opus of propaganda, which documented a Nazi Rally in Nuremberg), she agreed when Hitler promised her an unlimited budget and full artistic control (via Holocaust Encyclopedia). She went on to exercise that control, though unfortunately, she used it to glorify Nazis.

In cinema, some pretty simple tricks can influence how your brain processes and understands a scene. For instance, shooting someone from a low angle can make that person look more powerful. Moving the camera can give a scene a more kinetic, fast-paced feel. Cutting from one shot to another suggests a connection between them. Riefenstahl pioneered a lot of those basic techniques in "Triumph of the Will," and filmmakers still use them today.

"Triumph of the Will" won numerous awards, including the Grand Prix at the Paris World Exhibition. Some saw it for what it was, though; American filmmaker Frank Capra ("It's a Wonderful Life") famously called it a "psychological weapon" (via Film Inquiry).

She tried to distance herself from the Nazis by using concentration camp detainees as extras

After "Triumph of the Will," Riefenstahl continued to make Nazi propaganda, including "Olympia," which documented the 1936 Berlin Olympics. It also furthered Riefenstahl's penchant for cinematic innovation, including a technique she developed for vertical tracking shots, which involved rigging the camera to a flagpole. (That same flagpole was also supporting a swastika flag, reports DW.)

As World War II broke out, though, Riefenstahl began to regret her support of Hitler's regime, at least a little bit. When Hitler's troops rolled into Poland, Riefenstahl, who was present to document it, found herself shocked by the executions of civilians, and actually left her film set to ask Hitler to stop it. That worked about as well as you probably think. And, of course, Riefenstahl continued to work on her propaganda film.

As she became disillusioned with the Nazi Party, Riefenstahl yearned to get away from documentaries and direct more features, leading her to write, direct and star in "Tiefland," based on Eugen d'Albert's opera of the same title. The script called for "gypsies," though, and "She 'borrowed' some Romani detainees from a Nazi concentration camp" (via Holocaust Encyclopedia).

Riefenstahl had trouble completing "Tiefland" during the war, but it was eventually released in 1954, long after nearly all of her extras had been returned to the camp, shipped to Auschwitz, and killed.

She won 50 libel suits

Despite essentially being the queen of Nazi propaganda, though, Riefenstahl never actually joined the Nazi Party, and no one could ever prove she sympathized with Nazi ideals any more than the average German of the time. During the "denazification" process, the prosecutors failed to get any charges of war crimes stick against her. To the end, Riefenstahl insisted that she knew nothing of Hitler's worst deeds until after the war, and that her own contributions were only about the art of cinema. No one could prove otherwise (via Britannica).

In fact, Riefenstahl filed and won 50 libel suits against critics who accused her of being a Nazi. The one main exception — and it's kind of a big one — had to do with the production of "Tiefland" (via Independent). In 1987, Riefenstahl attempted to sue the director of the documentary "Time of Darkness and Silence," which showed her usage of Romani prisoners. While it was found that filmmaker Nina Gladitz had stretched the truth a bit by claiming Riefenstahl knew the prisoners would be executed, the court ruled against the bulk of Riefenstahl's claims of innocence.

In 2002, Riefenstahl was taken to court by Romani families and forced to issue the following statement: "I regret that Sinti and Roma had to suffer during the period of National Socialism. It is known today that many of them were murdered in concentration camps" (via Semicolon).

Her later contributions? Mostly underwater photography

Despite managing to get herself officially declared "not technically a Nazi" and "not technically a war criminal," though, Riefenstahl was unable to resurrect her filmmaking career after the war, finding herself blackballed. Although not allowed to work in the industry again, Riefenstahl managed to live to the age of 101, finally dying in 2003, which is an awfully long time to not be allowed to do the one thing you love. Since she couldn't hack it as a filmmaker anymore, Riefenstahl turned to cinema's older, nerdier cousin, photography, and actually published several influential books of her pictures (via DW). Two bestselling books, "The Last of the Nuba" and "People of Kau," documented the various Nuba tribes of Africa. If you're thinking these demonstrated a departure from Nazi ideals, reviewers at the time didn't see it that way. Susan Sontag, writing for The New York Review of Books (posted at the University of California, Santa Barbara) accused her of continuing to chase the same old "fascist aesthetics."

Perhaps more interesting, though, Riefenstahl actually won some acclaim as an underwater photographer with her books "Coral Gardens" and "Impressions Underwater," both of which pioneered several underwater photography techniques. In 2002, at the age of 100, she released a documentary based on the latter book (via IMDb), her first film since "Tiefland," and her last. Riefenstahl died September 8, 2003. According to Find a Grave, she's buried in a Munich cemetery.