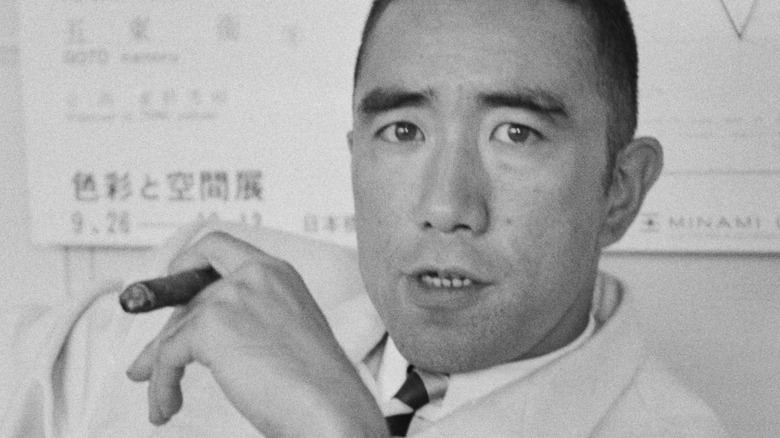

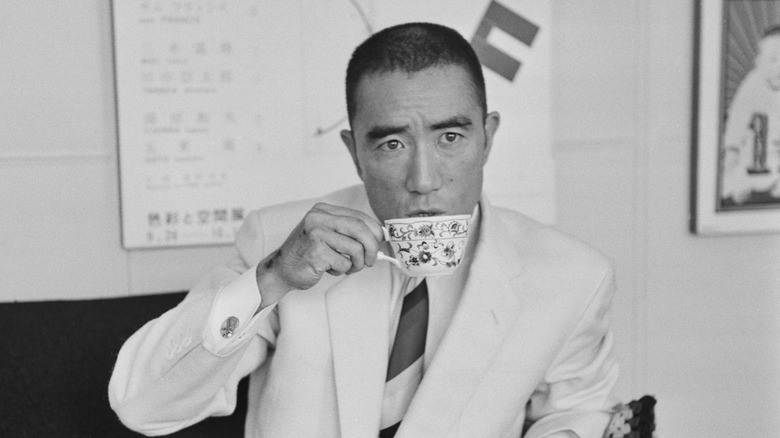

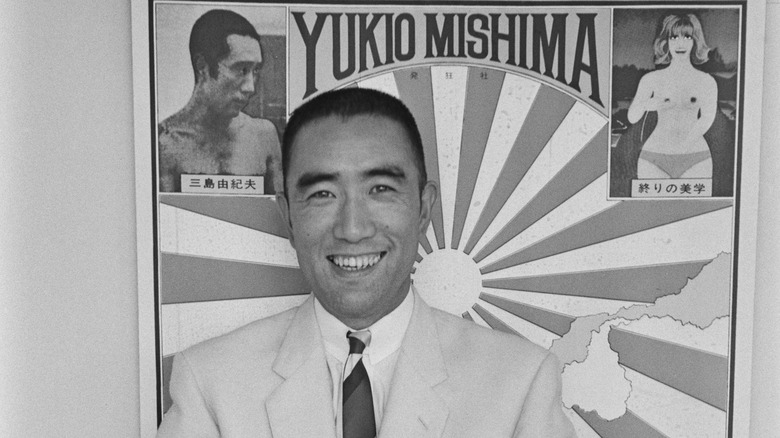

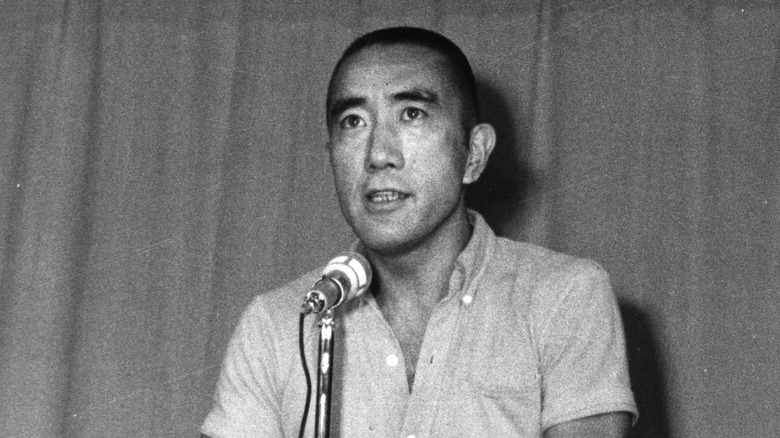

Yukio Mishima: The Life And Tragic Death Of The Japanese Author

This article contains references to suicide. If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

In his final moments, Yukio Mishima became the type of performance that he spent his entire literary career trying to distinguish from reality. But like the tension that his novels deal with, it's unclear whether this final performance was the effect of his failed actions or a deliberately executed farewell.

During his life, Mishima was rejected by liberals and conservatives alike despite his nationalism, but his novels still maintained a grip on the Japanese literary scene. In the 21st century, many of Mishima's previously untranslated works are finally available in several languages, including English. And Metropolis notes that "his varied career produced a book for everyone, no matter their taste."

Mishima's last work, "The Decay of the Angel," was completed in August 1970. Three months later, on November 18th, Mishima wrote to Fumio Kiyomizu, saying that "To me, finishing this [book] is nothing more than the end of the world." Just one week later, Mishima would die by suicide. This is the tragic life and death of Yukio Mishima.

Yukio Mishima's early life

Mishima Yukio (三島 由紀夫) was born Hiraoka Kimitake (平岡 公威) in Tokyo, Japan on January 14, 1925, to Hiraoka Azusa and Shizue. Mishima also had two younger siblings, Mitsuko and Chiyuki, but Mitsuko died from typhus when she was 17 years old, writes The Famous People.

When Mishima was born, he was taken to be raised by his aristocratic grandmother, Natsu. However, she was incredibly strict and never allowed him to play with other boys outside. According to Rochester University, the only time Mishima was allowed to see his mother was during the scheduled and timed breast-feeding sessions. Until Mishima's grandmother passed away, he almost never left her room or even saw sunlight.

Mishima was 12 years old when he was reunited with his parents. However, to his father, who was a fan of military discipline, Mishima came back a "weak, sickly boy" so his father repeatedly tried to "harden" him. Meanwhile, Mishima's relationship with his mother ended up eventually being described as "incestuous." One story describes Mishima as licking his mother's foot in the presence of others when she complained that it was sore.

Mishima's early writing

After getting back to his parents, Mishima's father tried to make him more "masculine," which often involved doing things like holding Mishima up "against a speeding train." And unfortunately, according to Culture Trip, Mishima's father thought that writing was "feminine" and would tear up Mishima's books and journals if he ever found them.

But according to The Famous People, Mishima was always an avid reader and he started writing his own stories at the age of 12. And having learned English, French, and German at Gakushūin, the Peers' School in Tokyo, Mishima became interested in European literature as well as traditional Japanese literature. Yabai writes that Mishima was originally interested in writing waka, or Japanese poetry, but before long he'd moved on to solely writing prose.

Some accounts claim that "Mishima Yukio" ended up being a pen name that Mishima would take up later in life so that his father wouldn't know that he was writing. But other sources claim that Mishima's teachers came up with the pen name "to save him from the ire of his fellow students."

By 1939, Mishima had several short stories published. But then during World War II, Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army.

Yukio Mishima was almost drafted into the Imperial Japanese army

In 1944, Yukio Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army. But although he was initially accepted for military training, during a physical the doctor misdiagnosed Mishima with tuberculosis, since he arrived with a cough and a fever from a bad cold, and relieved him of duty. According to Unseen Japan, had Mishima been approved for military service, he would've been sent to the Philippines and likely lost his life.

Some sources claim that Mishima felt far from relieved. Authors Calendar writes that Mishima was "plagued" by the fact that he "survived [the war] shamefully" while so many others ended up dying. But The New York Times, in comparison, claims that Mishima told a friend that he'd "laughed out loud with relief" after the examination.

Instead, Mishima went on to graduate from high school in 1944, and even ended up seeing Emperor Hirohito at his graduation ceremony, describing him as "magnificent on that day." Afterwards, Mishima studied law at Tokyo University, and briefly worked in the Finance Ministry. But after eight months, Yabai writes that Mishima resigned "due to severe exhaustion." Mishima's disinterest in finance was so noticeable that his superior Kiichi Aichi reportedly tells people that he was the one to suggest to Mishima that he should simply quit and dedicate himself to writing.

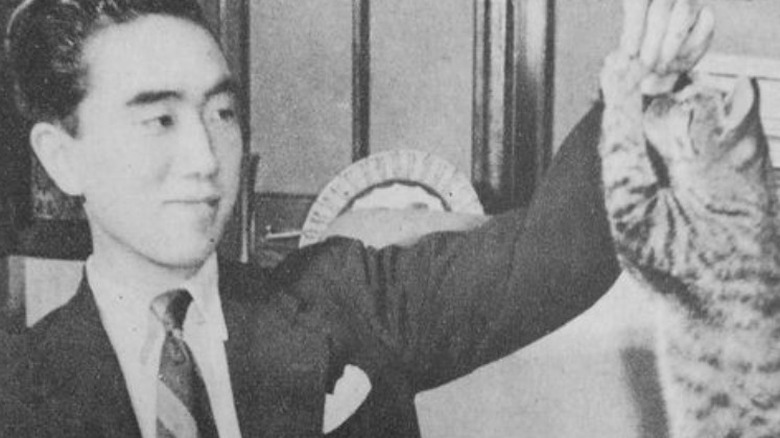

Becoming a published author

Yukio Mishima's first book "Hanazakari no Mori" (花ざかりの森) was published in 1944, but it was his first major novel "Confessions of a Mask" (仮面の告白), which came out five years later, that established Mishima as an intriguing and up-and-coming author in the Japanese literary scene. According to Unseen Japan, during this time Mishima also became friends with author Kawabata Yasunari, who encouraged and helped Mishima with his writing. As a result, Mishima created "at an astonishing rate," writing not only novels, but essays, plays, and poetry as well.

The BBC writes that "Confessions of a Mask" is somewhat autobiographical, telling the story of a young boy whose grandmother is holding him captive. As the main character grows, his preoccupation with fantasy, since he never quite gets to experience reality, finds an outlet in the theater. And as a young man, the main character reckons with "the entwined evolution of his internal and external lives and his homosexual awakening."

As Making Queer History notes, Mishima was likely either gay or bisexual, but it's impossible to know for certain. In any event, in 1958, Mishima married Yoko Sugiyama and they went on to have two children.

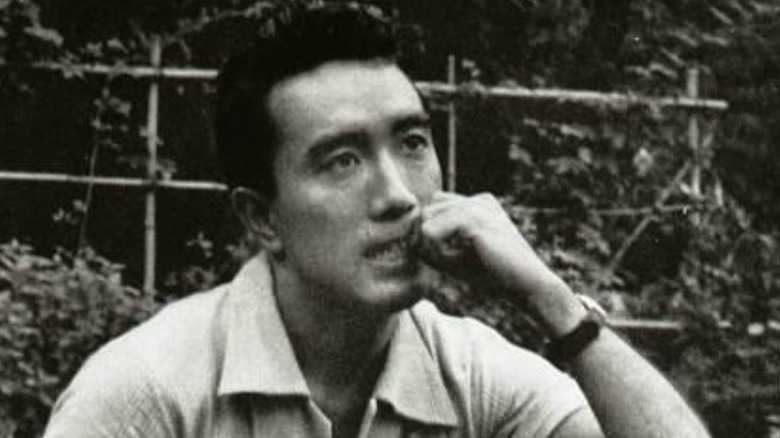

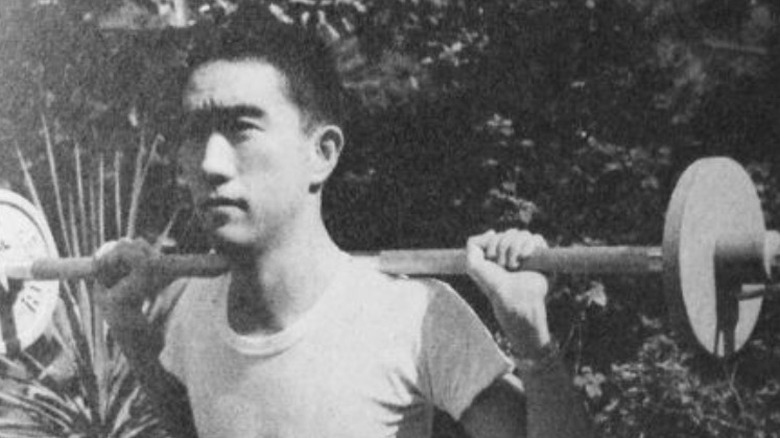

Obsession with physical form

As Yukio Mishima aged, he seemed to inherit his father's obsession with discipline and implemented a body-building regime for himself. Unseen Japan claims that Mishima's passion for bodybuilding came after a man he went on a date with "mocked him for his flabby physique." But regardless of what inspired his pursuit, soon Mishima was known not only for his writing, but for his obsession with the ideal body.

According to The Stanford Daily, in the autobiographical essay "Sun and Steel" (太陽と鉄), Mishima describes how he sought to attain the ideal body over the course of 10 years. In this essay, Mishima also derides the idea of mind over body, underlining instead a "glorification of the senses."

After working out for two hours every day, Mishima would also bronze himself in the sun. And before long, he was leading university students on workout routines as well as part of their training for the Shield Society, per the BBC. In addition to body-building, Mishima also took up kendo, which he was interested in because it brought one to the "border of life and death," writes Culture Trip.

Yukio Mishima's political views

Today, Yukio Mishima is most known for his attempted coup to restore the divinity of the Emperor of Japan, but his right-wing views were considerably well known at the time in Japan. However, according to Unseen Japan, Mishima broke with the traditionalist right wing in Japan due to his belief that Emperor Hirohito "should have admitted fault for the atrocities of World War II."

Meanwhile, according to Multitudes, Mishima was derided in the leftist press as a "fascist" as early as 1954. But although Mishima claimed that the leftist press uses the term fascist so much that the term no longer had any meaning, the description wasn't too far off. According to "The Ethics of Aesthetics in Japanese Cinema and Literature," the movement to resurrect the emperor was a neo-fascist movement. Mishima himself claimed that the emperor was the "source of Japanese culture," and restoring the divinity of the emperor was essential, in Mishima's mind, towards the restoration of Japanese culture.

The Conversation writes that in addition to advocating for the restoration of Japan's emperor, Mishima also called for restoring power to the Japanese military, believing that both institutions "had been rendered impotent by a U.S.-imposed postwar constitution."

Mishima's literary career

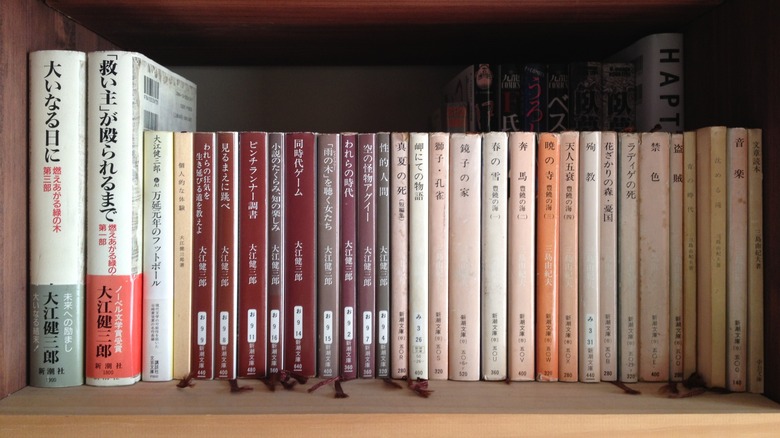

Throughout his life, Yukio Mishima ended up writing 40 novels, 18 plays, and almost two dozen volumes of essays and short stories. But although he was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize, writes The New York Times, he was never accorded that level of international recognition. Unseen Japan writes that the Nobel Prize was given to Mishima's mentor, Kawabata Yasunari, in 1968, at which point Mishima realized that it was unlikely that a Japanese author would win again for some time. But despite the lack of a Nobel, Mishima still had an international following, and many of his works were translated into numerous languages.

His 1954 novel "The Sound of Waves" (潮騒) ended up being based on his time in Greece, while the novel "The Temple of the Golden Pavilion" (金閣寺) is arguably Mishima's most famous work, based on the true story of when the Kyoto Zen temple was burned down in 1950.

New Statesman writes that most of Mishima's novels feature a recurring contrast "between the Japan that existed before it entered the Second World War and the desolate country that emerged afterwards."

Forming a private militia

In his desire to restore the emperor's divinity, Yukio Mishima advocated following bushido, also known as the moral code of the samurai. With this in mind, he created his own private militia known as Tate no Kai, or the Shield Society, in 1968. According to Culture Trip, the militia was made up of up to 100 university students who learned martial arts and physical discipline under Mishima's tutelage.

Mishima claimed that the students who joined the Shield Society were part of a "disaffected minority" of students who felt ostracized because their views didn't align with leftist ideology. But according to Artforum, although the creation of the Tate no Kai was part of Mishima's "dramatic gestures ... it was never strategic." It was, in a way, an extension of the modern Nō plays that he was writing, seeking "to move in a world of action that would challenge the inadequacy of language."

But nonetheless, the group met weekly, swearing to protect their "living god." Eventually, four members of Mishima's private militia would end up joining him in his attempted coup on November 25, 1970.

What was the February 26th Incident?

Also known as the Ni Ni Roko Incident, the February 26 Incident was an attempted military coup d'état that occurred on February 26, 1936. Yukio Mishima was only 11 years old when the coup occurred, but according to Asian American Writers' Workshop, he was greatly affected by it. According to The Japan Times, the ringleaders of the coup wanted to restore the Emperor "to his proper place" as leader of the military. Several governmental and military officials were assassinated during the coup and martial law was declared for three days.

Dozens were arrested, but their trials were held in secret with no witnesses, legal representation, or possibility for appeals. Nineteen soldiers ended up being executed, and 40 others were imprisoned. In total, up to 1,400 soldiers participated in the coup, but the majority of them were new recruits that were likely manipulated by the leaders of the coup rather than being ideologically driven.

Mishima wrote three stories based on the February 26 Incident, and even his own attempted coup would follow much of the same ideology as that of the 1936 coup. According to "Mishima's Negative Political Theology" by Akio Kimura, in the short story "Voices of the Heroic Dead" (英霊の聲), Mishima uses the executed members to recount the words of an ideal emperor; "So die in peace. You must die immediately." Ultimately, Mishima would follow these imagined words to his own death.

A coup to restore the emperor

Although Emperor Hirohito hadn't been forced to abdicate in 1936, a decade later he was forced to reject his status as a divine being. And on November 25, 1970, Yukio Mishima called out for a restoration of that divinity, in what would become known as the Mishima Incident. Along with Masakatsu Morita, Hiroyasu Koga, Masayoshi Koga, and Masahiro Ogawa, who were also members of Tate no Kai, they planned to persuade the Japan Self-Defense Forces to join their coup in order to overturn the 1947 constitution, according to Tokyo Weekender. However, one of Mishima's biographers, John Nathan, suggests that the entire coup was itself a ruse and that Mishima was planning to die by suicide the entire time.

The men got into the Ministry of Defense headquarters by scheduling an appointment with General Mashita, and once they got in they took him hostage. Going out onto the balcony, Mishima addressed the soldiers and asked them to join his coup. The BBC writes that earlier that morning, before heading off to start the coup, Mishima posted his final novel, the last book in the "The Sea of Fertility" tetralogy, to his publisher.

Unfortunately, the soldiers weren't impressed by Mishima, writes Yabai. Laughing and jeering at him, the crowd booed so much that most of Mishima's speech ended up being drowned out. Having planned to speak for 30 minutes, Mishima instead finished after seven minutes, ending with the exclamation "Long live the Emperor" three times.

Yukio Mishima's suicide

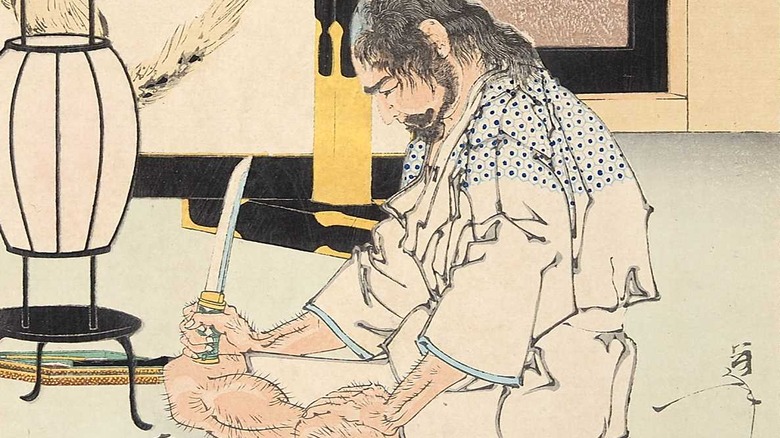

Despite the months of planning, Yukio Mishima was unable to rouse the support of the soldiers and he realized this relatively quickly. Tokyo Weekender writes that after failing to finish his speech, Mishima went back inside, explained to General Mashita what he'd attempted to do, and committed seppuku.

According to Asian American Writers' Workshop, this involved stabbing into his own abdomen and slicing from one end to the other. Following this, the person committing seppuku is beheaded by the kaishakunin. Masakatsu Morita was assigned to be the kaishakunin, and there are rumors that this was due to the fact that he and Mishima were lovers.

But once more, even with all the planning, this plan faltered as well. Morita made three attempts to behead Mishima but failed each time and hit his shoulder instead. Hiroyasu Koga had to take over and after successfully beheading Mishima, he beheaded Morita as well, who also committed seppuku. Although the three survivors were arrested, part of Mishima's meticulous planning involved making sure that they had enough money for their legal defense, since they were likely to be charged not only with the coup, but for assisting in the seppuku.

What is seppuku?

Also known as hara-kiri, seppuku is a type of ritual suicide. Primarily practiced by daimyo and samurai of Japan, seppuku revolved around slicing the stomach open with a sword, which according to ThoughtCo, was believed "to immediately release the samurai's spirit to the afterlife." Seppuku also involves a second person, who is responsible for decapitation, a process known as kaishaku. The deception is necessary to put an end to the pain of the abdominal cut, and if done correctly, "the head would fall forward and look like it was being cradled by the dead samurai's arms."

Seppuku was committed for a number of reasons, often related to the reputation of the samurai. But during the Tokugawa shogunate, seppuku was also used as a form of punishment. While battlefield seppuku was often performed quickly, planned seppuku was an "elaborate ritual." And people of all genders are known to have participated in seppuku.

According to "Culturally sanctioned suicide" by Joseph M Pierre, seppuku started being practiced as early as the 700s, though some sources put the earliest seppuku in the 12th century. In 1873, it was formally outlawed, but despite the ban, seppuku still occurred. Listen To The World writes that Nogi Maresuke committed seppuku on the day of Emperor Meiji's funeral. General Korechika Anami also committed seppuku after Japan surrendered in World War II.

The trial of the survivors

On March 23, 1971, Hiroyasu Koga, Masayoshi Koga, and Masahiro Ogawa were put on trial for their role in the coup and assistance in Yukio Mishima's seppuku. According to The New York Times, this was the first time in Japanese history that the assistance in seppuku was "the basis for charges under a modern criminal code." All three of them were former students. The two unrelated Kogas were former Kanagawa University students and Ogawa was a former Meiji Gakuin University student, writes The Japan Times. Meanwhile, records from the trial ended up showing that Mishima started planning the coup as early as March or April 1970. Interestingly, this was around the same time as he started reworking the plotline for "The Decay of the Angel" (天人五衰), his final novel.

In addition to being charged with "murder by request," Hiroyasu Koga, Masayoshi Koga, and Masahiro Ogawa were also charged with assault and battery, illegal possession of firearms, and illegal confinement. And when asked about their motivations, The Age writes that they claimed to have assisted in the seppuku because "they were ready 'to die like dogs' to save Japan from spiritual decay."

Waiving their right to a jury, on April 27, 1972, the three men were found guilty. For their role in both the coup and seppuku, they were sentenced to four years imprisonment. In 1974, all three were released early on good behavior, after serving most of their four-year sentences.

The legacy of Yukio Mishima

At the time, reactions to the Yukio Mishima Incident among the public were mixed. Tokyo Weekender writes that while the writer's fans thought the seppuku was "a noble and gallant sacrifice," others considered it to be "a potentially dangerous act by a narcissistic man." Eisaku Sato, the prime minister at the time, stated, "I can only think he went out of his mind." Meanwhile, according to The Guardian, most other politicians simply considered the act to have been vain and useless: "At best, an artistic performance by a showman and, at worst, a futile gesture by a deranged extremist."

But in the 21st century, Mishima still has supporters who claim that his "ultimate act of self-sacrifice is at last being proved to be an important political milestone." Since the end of the Cold War, many of the ideas that Mishima was addressing are started to be debated amongst the public.

As a writer, Mishima continues to be regarded as a strong force in Japanese literature. Despite his nationalistic fervor, his works find themselves preoccupied more with the tension between reality and performance. In the end, his final act in life toed the ambiguous distinction between the two that his novels sought to collapse.