Here's What It Was Like For Prisoners In Devil's Island

Who doesn't love the thought of life on a tropical island, palm trees blowing gently in the wind, the tides bringing little gifts of seashells and driftwood, shorebirds calling out to each other, coconuts for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Sounds like paradise, right? Unless you don't happen to like coconuts.

Well, not all tropical islands are synonymous with paradise. In the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, you could get a one-way ticket to a tropical island that was widely believed to be the closest you could get to hell on Earth, complete with torture, disease, hunger, and large, angry prisoners.

Devil's Island was a French prison system located off the coast of French Guiana in South America. If you were sentenced to do time there, well, that was pretty much the same as a death sentence, only not as much fun. Prisoners on Devil's Island didn't have the same perks as prisoners do today — there were no movie nights or libraries, no prison store, no telephone calls to the outside world, and no actual human rights. Now, the actual human rights of today's prisoners may still be a subject of debate, but there's no real debate about the horrors inflicted on Devil's Island prisoners, who lived a tortured existence that was almost always disproportionate to their actual crimes. Let's just say that after you read this, you might actually decide that modern prison sounds kind of like a four star hotel.

French Guiana was terrible even before it was penal colony

Here's the thing about French Guiana: With the possible exception of the original, indigenous inhabitants (and we can't really say what the Arawak and Caribs thought of the place since Europeans displaced them a few centuries ago), French Guiana sucked for everyone who tried living there, even the people who colonized it on purpose. According to the Journal of the Western Society for French History, early attempts to settle French Guiana were disastrous, not just because of the lousy weather and the tropical diseases, but because the French didn't really think things through before they sent people out there to build a colony. In the 1760s, between 13,000 and 14,000 French colonists tried to settle French Guiana, and within a few years there were only five or six thousand left. The rest were dead.

Still, the French had worked pretty dang hard to steal French Guiana from the natives and also from the Dutch, so they figured they'd better find some use for the godforsaken place. First, they decided to turn it into a leper colony, thus giving it a reputation as a place where you sent people you didn't want to have to think about anymore. From there, it wasn't a huge leap to turn the place into a prison, since the only people who would go there willingly were pretty much no one, and what else are you going to do with a place like that?

It was this guy's idea

So there was definitely a need for Devil's Island to end up as something given that no one was going to move there voluntarily, but why not turn it into like a coconut factory or seagull breeding facility or something? Whose bright idea was it to send human beings there to die a lonely, forgotten, and tortured death?

According to Atlas Obscura, Napoleon III (nephew of the much more famous Napoleon I) made Devil's Island into his own human dumping ground when he established it as a prison in 1852. Now, you would think that a place as remote and inhospitable as Devil's Island would be reserved for only the worst of the worst — murderers and other violent criminals, perhaps — but nope. Devil's Island was where the third Napoleon sent people whose opinions he didn't like, like pretty much everyone who didn't think he should be in power. It also housed a lot of violent criminals, though it's probably not a stretch to say that the violent criminals might have been there at least partially because they helped make the prison an unfriendly place for all of Napoleon's enemies. Sadly, lesser criminals went to Devil's Island, too, where they mingled with and were sometimes murdered by the violent criminals.

Devil's Island wasn't just the one island

History remembers "Devil's Island" in the singular, but there were actually three islands. Officially called the Îles du Salut (which ironically means "Salvation Islands,") each of the islands had a different role to play in the overall prison system (there was also a facility on the mainland). According to the Daily Telegraph, the island called "Île du Diable," which means "Devil's Island," was reserved for those who made the most trouble for the French government, like traitors, political dissidents, and the like. On the up side, there was only room on the island for 12 people, so there was less conflict with troublesome neighbors. Alfred Dreyfus, one of the island's most famous prisoners, said that because Île du Diable was considered escape-proof, residents got to roam around mostly unrestricted. Which sounds great until you consider that there really wasn't anything good about the place, so it's not like your free movements included piña coladas on the beach, bay cruises, and room service.

A second island, called Île Royale, was the reception area, where prisoners would be processed and welcomed to their brand new, hell-on-Earth existence. The third island, Île Saint Joseph, was where you got sent if you were very, very bad (prisoners who tried to escape from the prison were put in solitary confinement on Île Saint Joseph, sometimes for as much as five years). The mainland was where the general population was housed, with the islands reserved for the worst offenders.

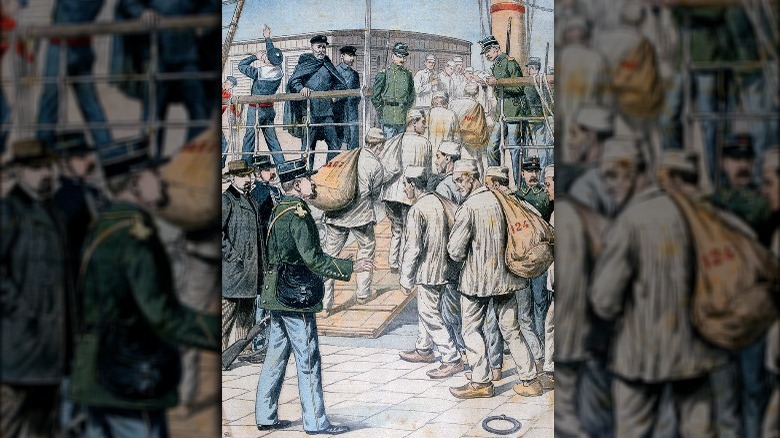

Life sucked before you even got to Devil's Island

Once you got your Devil's Island sentence handed down, it was pretty much all downhill from there. Convicted criminals received third class tickets on passenger ships, where they were forced to sleep on cots in overcrowded rooms with crowds of other people and had to eat subpar food and drink warm water. Just kidding, it was nowhere near as luxurious as that. According to a 1928 account of Devil's Island published in the Sydney Morning Herald, once a criminal was sentenced to prison on Devil's Island, he was stuffed into a steel cage below decks on a prison ship with 100 other convicted criminals, side by side with more cages containing more criminals. The prisoners' water was kept outside the cages in barrels, and to get at it they had to reach through the bars. It was oppressively hot below decks, and almost certainly became progressively hotter as the ship sailed south towards its destination. The account doesn't mention what happened to prisoner poop, but it's probably a safe bet that there wasn't any indoor plumbing.

Even if those ships' holds had been full of law-abiding citizens, tempers would have been pretty hot in those conditions, but these were criminals — many of them, anyway — and what's more they were criminals who had nothing left to lose. Fights were so common that the cages were fitted with pipes that sent out jets of scalding hot steam whenever tempers got out of control.

The survival rate was roughly 38%

If you were sentenced to prison on Devil's Island, you could expect your mortality rate to be around 62 percent. Just to put that into perspective, bird flu (H5N1), that terrifying and highly lethal strain of influenza that's poised to one day become COVID x1000 has a similar mortality rate, and so does stage 1 lung cancer.

Having said that, accurate statistics on just how many prisoners were sent to Devil's Island and how many actually got out again are elusive, probably because the French didn't think it was super important to keep track of all the people they sent there, given that the government mostly just hoped people back home would forget they had ever existed. Some estimates say that only 2,000 prisoners actually survived their ordeal, which means the mortality rate was closer to 97%. If that statistic is true, then your chances of surviving stage IV lung cancer today are basically the same as your chances of surviving Devil's Island would have been.

According to the Daily Telegraph, by 1928 France was sending around 1,200 men to Devil's Island each and every year, and yet each and every year the prison population would decline by around 400. It doesn't take a math wizard to figure out why. After 75 years, life for Devil's Island prisoners was just as horrific and dangerous as it had been in the 1850s, and the French government had no incentive to change anything.

Sharks. Because of course sharks.

Îles Royale and Îles du Diable are only 600 feet apart, so it seems like you ought to be able to use one as a springboard for the other, and perhaps go from there to freedom on your makeshift raft made out of coconuts and clamshells. So why didn't more prisoners take their chances on the open water, especially considering the fact that they were able to free range on Îles du Diable? Here's the answer: Sharks. Yes, sharks.

The reason early colonists dubbed one of the three islands "Devil's Island" was because the waters around it were full of sharks. So if you tried to sail away on your makeshift coconut raft, it would probably only take a few minutes for the neighborhood sharks to decide your coconut raft looked as delicious as you do. And prison officials were painfully aware of the deterrent effect of sharks, so much so that they liked to encourage the beasts to stick around and wave their fins at would-be escapees. How did they do that? According to the Australian Museum, every day at 4pm they would dump dead prisoners into the shark infested waters, which was not just a handy way to have a fuss-free funeral, it also gave the sharks a taste for human flesh and a good reason to stick around. Plus, prisoners got an advance look at what would happen if they decided to leave on a raft made of coconuts. Everyone wins.

Living conditions were progressively worse depending on which part of the prison you were in

While the residents of Devil's Island itself were roaming freely around the beaches, watching corpses get devoured by sharks, eating coconuts or whatever else they were doing, residents of the other three parts of the prison system lived a little differently.

If you were housed with the general population on the mainland, you got to live in a cell, but that's where the luxuries ended. Still, life on the mainland beat life on Île Saint Joseph. According to the LA Times, if you were unlucky enough to get a solitary confinement sentence, you got to live on Île Saint Joseph in an underground cell with bars on the ceiling. You could see the guards through the bars, but you weren't allowed to talk to them, and you were subject to getting rained on or worse because your barred ceiling didn't have any shutters. And if venomous centipedes, spiders, or whatever other creepy crawlies wanted to come down and join you for the evening, well, there wasn't much you could do about it because it's not like you could see them well enough to stomp on them. You were also forbidden to sit down until nightfall, when it was so dark you really couldn't tell what you were about to sit on. So you probably had to weigh "how exhausted am I" against "how badly do I want to sit on a large rodent." Fun stuff.

Mainland prisoners were put to work

Just because you weren't on one of the islands doesn't mean your life was easy. Prisoners on the mainland had 12-hour work weeks, and it wasn't even anything so pleasant as scrubbing prison toilets or peeling potatoes, either. According to the Daily Telegraph, mainland prisoners went to work at 6am and finished up at 6pm. Now, 12-hour days don't seem so bad especially if you work in a profession like nursing or firefighting where 12 hour shifts are already a fixture of your daily life. But Devil's Island prisoners didn't have break rooms or coffee or, you know, shoes, and they were doing hard, manual labor in inhospitable conditions, often without protection from the sun or three meals a day.

If that wasn't already horrible enough, nothing the prisoners did was of any actual value. They chopped down trees for farms that were never planted and built a road that wasn't actually meant to ever be used. Called "Route Zero," the road was 15 miles long and remained under construction for more than 50 years, mostly because its only purpose was to provide prisoners with backbreaking busy-work. Still, a prisoner who failed to meet his arbitrary quota didn't get to eat, which became a self-fulfilling prophecy, really, since it's pretty hard to meet a quota when you are weak from hunger.

The end of your sentence wasn't really the end of your sentence

Modern prisoners look forward to the day they will be released, because it means leaving their harsh former existence, returning to their families, and maybe even learning how to live a normal life. Prisoners at Devil's Island had no such future to look forward to, even if they did manage to survive the torture and confinement of the prison.

According to the Daily Telegraph, mainland prisoners who got to the end of their sentence then received a reward known as "doubleage," which basically just meant that they got to do all their prison years over again, only as workers in French Guiana. Before you decide that's maybe not so bad compared to life in prison itself, remember that not so long before Devil's Island was established, thousands of colonists died trying to make lives for themselves in French Guiana, so it's not like ex-prisoners serving doubleage were living in nice apartments and working comfortable office jobs. It was really just prison outside of prison. Worse, if your original sentence was longer than eight years, then your "doubleage" became what should have been called "foreverage," and you had to keep working in French Guiana for the rest of your life. So in other words, except for a very lucky few, Devil's Island prisoners never finished paying their debt to society, no matter how small or large the crime. They just kept on paying until they died.

Also this other stuff that sucked

Prisoners were barely allowed to talk, eat, or rest, so it probably won't surprise you to hear that they also didn't get to have bug spray or rat traps. According to the LA Times, prisoners were plagued by mosquitoes, ants, and other bugs. One prisoner even described laying still in his dark cell while venomous centipedes crawled all over him. Also, wounded prisoners were sometimes infested by the flesh-eating larvae of screwworm flies. Also present on the island: rats and vampire bats. Some older accounts of life on the island talk about alligators, so just in case the sharks off shore didn't worry you, there were plenty of dangers out in the jungle, too.

Of course, what's a few rat bites compared to what another inmate could do to you? Prisoners were already non-persons with what might as well have been life sentences, so if an inmate was predisposed to violence there really wasn't anything working to deter him from slitting a fellow inmate's throat with an oyster shell because it was Wednesday and his steak was overcooked (just kidding, no one got steak).

Some inmates walked around in chains all day and some were chained up at night, too. And you have probably already guessed that there were diseases — mosquito-borne illnesses like malaria and dengue fever swept undeterred through the population, as did diseases related to poor sanitation like cholera, typhoid fever, and dysentery.

You might survive all of that only to become a crazy person

Today, just about everyone agrees that solitary confinement is a messed-up thing to do to another human being. Many nations are taking steps to end or restrict the practice, and notable world leaders have spoken out against it, including the late prime minister of India Jawahar Lal Nehru who called it "a most painful affair" and a "killing of the spirit by degrees, the slow vivisection of the soul. Even if a man survives it, he becomes abnormal and an absolute misfit in the world."

Welp, none of that mattered to the French government or the guards at Devil's Island, who knew exactly what could happen to a person who was locked up in a dark room for two or more years. When it became clear that the men who came out of solitary confinement were not the same as the men who went in, the French government didn't change any of its practices and policies. Instead, it just built insane asylum cells on Île Saint Joseph just down the block from the solitary confinement cells, so it would have a place to keep all of its newly-minted crazy people. According to the Daily Telegraph, the screams that came from the insane asylum part of the island were like "howling monkeys," so you know, at least they somewhat contributed to the tropical paradise ambience of the place.

A few prisoners risked impossible odds in the hope of escaping Devil's Island

Most prisoners looked out at the shark infested waters and just accepted their lot in life. But a few prisoners decided that becoming shark food was infinitely better than starving to death or being eaten by rats, and decided to go out with a bang, or a crunch, depending on how far they actually got. According to a 1924 article published in the Townsville Daily Bulletin, some of the men devised brilliant escape plans, like the guy who stabbed himself, feigned death and then escaped from the morgue with the operating table, which he used as a raft. (To be fair, he only had a shoulder wound so the success of his plan depended on the stupidity of the medical examiner.) Another prisoner had himself nailed inside a crate labeled "Rare Plants. Keep away from boilers, and water frequently." Neither of these stories mention whether or not the escapee survived the escape itself, but it's nice to think they did.

A couple of verified escape stories exist — the most famous was that of Paris gangster Henri Charriere, who did actually escape on a raft made of coconuts (although a lot of what he claims has been called into question). He ended up settling in Venezuela, where he eventually opened a nightclub. Yes, a nightclub. Charriere later wrote a book called "Papillon" and was played by Steve McQueen in the 1973 movie of the same name, so you know, things didn't turn out so badly for him, at least.