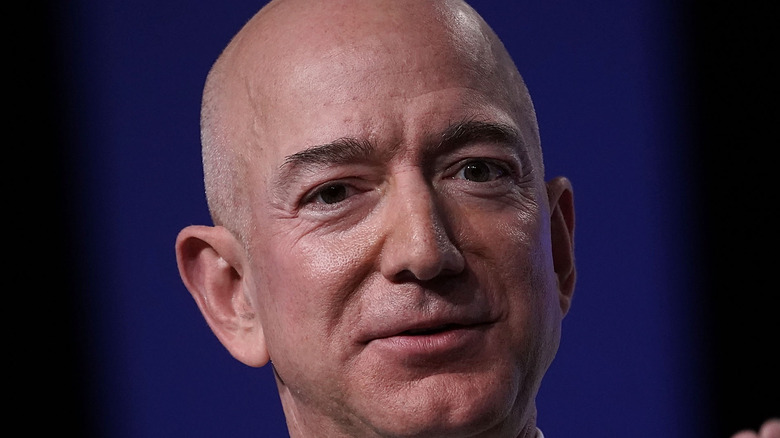

The Real Reason Jeff Bezos Is Only Traveling To The Edge Of Space

That's right, folks: The billionaires are starting to leave us. In what is likely a prologue to 2013's "Elysium," or more whimsically, Pixar's "WALL-E," Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk have taken to transforming the once U.S.-Soviet Union space race into a battle of industry titans lifting off from mountains of greenbacks. Branson made his flight on July 11 in a "rocket plane" (for lack of a much cooler name) dubbed "Unity," in the culmination of 17 years of engineering and planning, as well as a lifelong dream to go to space, per the BBC. He and a crew of five employees of Virgin Galactic made it to 85 kilometers (53 miles) above the surface, skimmed the contour of Earth's still-blue and beautiful sphere, and resettled back at Spaceport America New Mexico in little over an hour. Present for the launch was Branson's buddy and fellow billionaire, Elon Musk, while Bezos sent his congratulations by distance after the fact.

One look at Branson's Unity vessel should make it clear that it's not a standard rocket, in the way we might envision a NASA craft à la the Apollo 11 in the 1960s. It does have a detachable module for fuel to reach orbit, but it's more of a plane designed for commercial flights; this makes sense, given that planes are very much Branson's thing. Bezos' flight, on the other hand, will employ a much more traditional-looking rocket, as the BBC shows us. Both designs have the same goal, though: skirt the edge of space.

New Shepard will reach the Karman Line to create weightlessness

Looking at Branson's Unity, it's basically a plane-rocket-glider combo on a permanent loop. It has one flight plan, as the BBC shows us, up into the atmosphere to an apogee approaching 100 kilometers (62 miles), and then back into the Earth's atmosphere where it glides, unpowered, back onto the same runway where it started. Bezos' vessel, New Shepard, essentially does the same thing, except it shoots straight up, per the BBC, separates from its booster, and a passenger module hovers around the same 100-kilometer apogee like a little house before descending back into the atmosphere using a parachute. Unlike Unity, it lands at a different location.

So why 100 kilometers? Well, this is the "edge of space," otherwise known as the Kármán line, named after late 19th century Hungarian physicist Theodore von Kármán. Earth's atmosphere doesn't simply stop, and then space begins. The atmosphere is a gradient of air, as National Geographic says, where eventually "orbital dynamic forces become more important than aerodynamic forces." At 100 kilometers, folks can experience "free fall," where they're falling at a velocity equal to the force of gravity exerted on earthbound objects. Weightlessness, in other words.

This is why Bezos, and Branson before him, chose to surf along the edge of space. It's controlled enough for reentry, sure, and provides amazing views of our planet. But more importantly, it will afford future commercial space flyers the ever-important sense of weightlessness that they'll definitely want.